Daniel

Johnston, the legendary outsider artist beloved by Beck, Wilco, and Kurt

Cobain, is the subject of a new exhibition, Psychedelic Drawings, at New York’s

Electric Lady Studios. While best known as a singer-songwriter, Johnston – who

died in September 2019 of natural causes, after a forty year struggle with

severe mental illness – always identified as an ‘artist’ across the board, with

a reverence for comic books, cartoons, and drawing that predated his taste for

music.

Running

till 7th February and available to view online, Psychedelic Drawings is the

headline of this year’s Outsider Art Fair, an annual event that celebrates

artists from unconventional and neurodiverse backgrounds.

“The

psychedelic experience is partially defined as ‘an apparent expansion of

consciousness,’” says Lee Foster, the manager of New York’s Electric Lady

Studios. “Daniel went places that most of us clearly never go to.”

“What I

think is most fascinating about him is that he so compulsively documented what

he saw – like an explorer drafting the first maps of an uncharted space.”

Gary

Panter, an artist and the exhibit’s curator, describes Johnston as a

“self-taught visionary artist”. Exhibited in galleries around the world, visual

art was critical to Johnston’s appeal even from his earliest cassettes.

Notably, the delicate, marker-drawn cover of Hi, How Are You?, when worn on a

t-shirt by Kurt Cobain at the MTV Music Awards in 1992, is credited with first

catapulting Johnston into popular awareness.

“I think

Daniel was subject to an imagination turned up to eleven”, says Panter, who

selected thirty drawings for the exhibit. “He saw the things he drew in some

way similar to his drawings, but subject to the limits of drawing. It is hard

for drawing to really match imagination.”

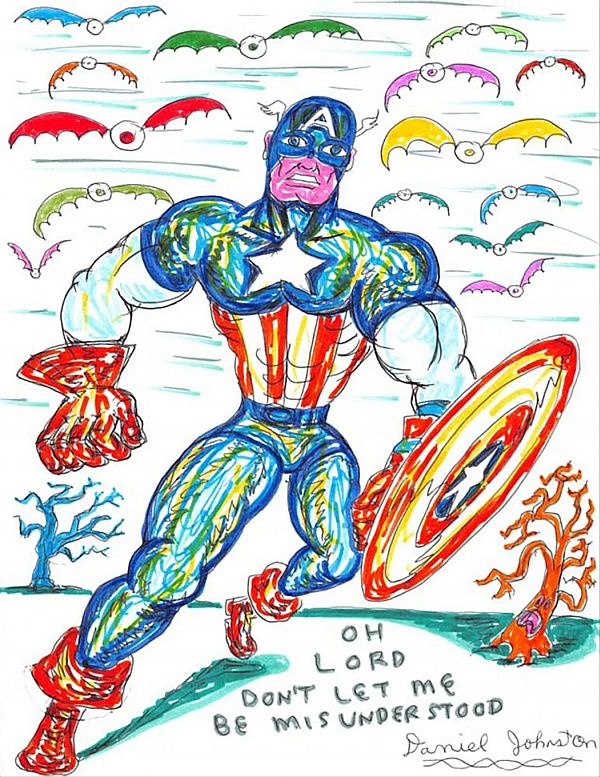

Johnston’s

sketches, like his songs, are messy, untrained, DIY: constructions of felt-tip

markers and bright, primary colours, which often cross outside the lines. Fans

of Johnston will notice, too, the appearance of characters like Captain

America, The Hulk, Frankenstein, and Casper The Friendly Ghost, who show a

remarkable constancy in the artist’s work.

In this

exhibit alone, Captain America features in pieces from as early as 1978 and

well up to the 2000s, in a style that’s remained broadly similar. “I forgot to

grow up, I guess”, Johnston told Rolling Stone. “I’m a simple kind of guy, just

like a child, drawing pictures and making up songs, playing around all the time.”

For

Johnston, however, these characters are more than nostalgic nods. In his

visionary schema – much like William Blake’s self-created mythology of fairies,

holy spirits, and goddesses – the characters hold a deeply symbolic status,

resonating on fundamental questions and grand tensions. In works like ‘I Dream

of Good Versus Evil’ and ‘Faith Is Belief’, Captain America personifies good

and wisdom itself, holding the airs of a mystic with short Zen-like snippets.

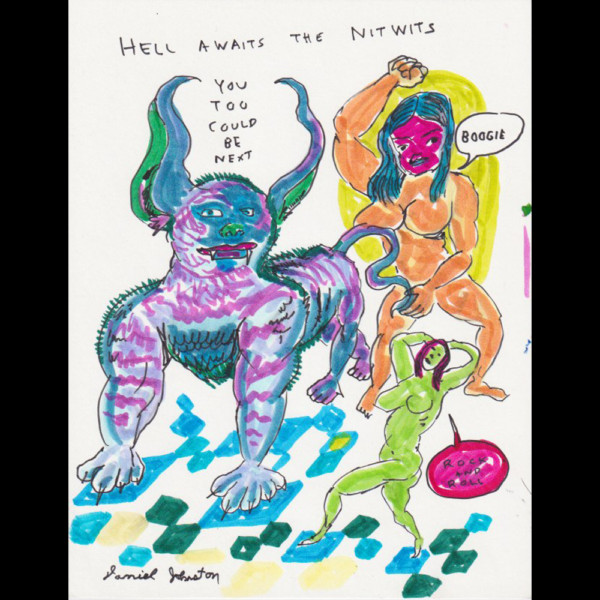

Equally,

Casper The Friendly Ghost seems to stand in for God (or Satan, it’s not clear)

in ‘You’ll Wait For Eternal Punishment’, where he flies over a quartet of

demons burning in hellfire. He explores hell again in 2001’s ‘Pain and

Pleasure’, a technically-striking depiction of deformed and neon-coloured

ghouls.

Indeed,

Johnston’s fascination with demons is well-known. As told in 2006’s The Devil

and Daniel Johnston, he refused a contract with a major label because they’d

signed Metallica, a band Johnston took as the work of Satan. Raised in the

fundamentalist Church of Christ, it seems that Johnston’s inner landscape was

wont to mix fiction, fantasy, spirituality, and biography from an early age.

Separating

truth from fiction was precisely Johnston’s problem, though. While a careful,

symbolic balance could be drawn in his artwork, the same characters would

emerge in Johnston’s most florid psychoses, and in ways that put paid to any

romantic view of mental illness. It was his manic delusion of being Casper The

Friendly Ghost, for example, that once led him to crash-land his father’s

plane; episodes of devil obsession ended in grievous assaults of an old lady

and his manager. The ‘psychedelic’ component of the exhibit at all, in fact,

produces a certain unease, being that Johnston’s major breakdown was triggered

by the abuse of psychedelic drugs.

It

doesn’t help that our culture tends to mythologise the link of mental illness

to creativity. Studies suggest that there is no greater likelihood for creative

types like musicians and writers to be mentally ill at all. It was at

Johnston’s times of more severe mental illness, in fact, when his creative

energies were most sapped. Prescribed psychiatric drugs, while essential for

preventing a relapse, would further dull the mind.

That

said, art therapy, where patients are encouraged to externalise their emotional

stress in pictures, has shown application in treating schizophrenia. It seems

that Johnston was doing much the same, albeit in a non-clinical setting. It’s

worth remembering that Johnston’s illness wasn’t always ‘cosmic’, either, in

the Blakean sense of grand visions and inner worlds. It was often classically

depressive.

‘Hulk

Will Smash’, sketched in 2000 at age 39, shows Hulk as an instrument for

Johnston’s own anger and self-doubt, especially over his inability to find

lasting romance. Or consider 1980’s ‘My Nightmares’, which depicts an

intimidation at the hands of a cyclops and a knife-wielding jack-in-the-box.

‘Hello Daniel. You’re nervous, aren’t you? Aren’t you?’, he asks.

“Daniel's

dealings with his illness was surely something that he channeled into his art

and music. But, we can't view his entire body of work in one single context”,

says Lee Foster of Electric Lady. “Each piece tells the story of how he was

feeling at a given moment, even minute-by-minute at times -- and then sometimes

years apart.

“I think

it was very much a mixture of his winning and losing battles with the forces

around him. The major themes focused on the fight itself and the always

underlying idea of hope.”

This

year’s Outsider Art Fair features a whole gamut of alternative voices. Panter,

Psychedelic Drawings’ curator, compares Johnston’s exhibit to those of Henry

Darger and Susan Te Kahurangi King, other “self-taught visionary artists” who

suffer(ed) respectively from bipolar disorder and a non-verbal form of autism.

With its

leading voices already drawn from the margins, though, some fear that ‘outsider

art’ itself can risk further slides away from popular acceptance. Those with

mental illness especially are defined into ‘outside’ - and therefore

victimised, stigmatised, and deprived - status.

They may

exhibit at major studios, but are ‘outsider artists’ being listed for the right

reasons? Andrew Edlin, the curator of this year’s Outsider Art Fair, gives his

take.

“Well,

any artist can be exploited regardless of their academic pedigree or state of

mental health. Any serious viewer of art first will be compelled by an artwork

itself, and then knowing about the conditions behind the creation, insofar as

the life story of the artist informs the artwork, will then glean a deeper

understanding.

“The

concept of the ‘outsider’ is appealing because it connotes non-conformity,

which is almost always good when it comes to art. We make sure that we treat

our artists or artist estates with the same professionalism and respect as in

any other sector of the art world. I feel that by recognising the talent of

people who have been dismissed or marginalised by society is the exact opposite

of exploitation. It’s an elevation and granting of respect and admiration.”

Steering

the lines of “admiration” and risky exploitation can be a delicate game. Those

most keen to link Johnston’s creativity to his illness, it seems, should accept

the burdens of such an assignment. A famous press release by Johnston’s

management team, for example, once called on journalists to avoid describing

him as a ‘genius’, given how it may affect his precarious sense of self.

Johnston himself was reportedly resentful of billing as a novelty act.

‘Frustrated

artist, are you afraid of your own reflection?’, he sang in 2000. “It’s only

you. Like I said, when you’re dead, you’ll be gone. It won’t take long till

you’re through.”

Daniel

Johnston’s Psychedelic Drawings: A Swirling Trip Through ‘Outsider Art’ By Ed

Prideaux. The Quietus, February 6, 2021.

Before

he garnered acclaim as a musician, Daniel Johnston was known in his West

Virginia hometown as a visual artist. He was compulsively creative with a

mischievous streak, drawing on any available surface and even veering into

vandalism when he ran out of paper. His calling card back then was a

free-floating eyeball he later referred to as a dead dog’s eye—an image sourced

from the Beatles’ “I Am the Walrus” and cemented in his psyche by a disturbing

incident as a teenager, wherein he came upon a hanged dog. Eyes were an

ever-evolving constant in Johnston’s drawings, either lying in a tangle of

cartoon veins at the margins or staring down upon his hellacious scenes. In the

dense personal mythology that grounds his work, eyes were symbols of innocence

and paranoia. Jeremiah, the cartoon frog that famously covers his 1983 album

Hi, How Are You, is the ultimate avatar of this: His two elongated eyes grew

into six over time, as he evolved into Vile Corrupt, Johnston’s figure for

ultimate evil.

Johnston’s

all-seeing eyes feature prominently across a series of drawings currently on

display at Electric Lady Studios in New York, as part of this year’s Outsider

Art Fair. Curated by artist and comics legend Gary Panter, Daniel Johnston:

Psychedelic Drawings is the first significant exhibition of Johnston’s work

since his appearance in the 2006 Whitney Biennial, as well as the first since

his passing in 2019. The show offers an opportunity to consider Johnston’s

drawings not only in the context of his homespun musical universe but within

the broader realm of American art. It is the most extensive collection of his

visual work to date.

The

exhibition is the product of Panter’s discerning eye as much as it is the

enthusiasm of Lee Foster, Electric Lady co-owner. After purchasing a sketch of

Johnston’s off eBay in 2019, Foster began a correspondence with Johnston’s

brother and executor of his estate, Dick, as well as his former manager, Jeff

Tartakov. The resulting friendship led to a business relationship between

Electric Lady and The Daniel Johnston Trust, wherein the studio will assist

with the sales and licensing of his work.

Psychedelic

Drawings continues the estate’s strategy of amplifying Johnston’s art through

mainstream commercial projects, which included a short film and a comic book

during his last years, and capsule collections with Vans and Supreme more

recently. While these endeavors arguably help fuel the ongoing reappreciation

of Johnston’s music, they sit at odds with the elite art world’s preference to

hoard work from public view, save for a fawning crowd of cognoscenti. The show,

which runs physically and digitally through February 7, is pitched by Foster as

a more inclusive cross-pollination between art and music that could nonetheless

facilitate a critical reappraisal of Johnston’s visual work.

Johnston,

who battled schizophrenia and bipolar disorder during his lifetime, has always

been tricky to categorize in strict art terms. He was too pop to be true

“outsider art”—a contentious genre used to group work by marginalized artists

(whether incarcerated, mentally ill, or self-taught)—but too “outsider” to be

fully pop. And yet he is the rare figure, “outsider” or otherwise, to have been

celebrated during his own lifetime and to have reached a cult audience more

mass than most established contemporary artists could ever imagine reaching.

For many, Johnston’s visual art is inextricable from discovering his music,

whether via Jeff Feuerzeig’s classic 2006 documentary, The Devil and Daniel

Johnston, or the well-loved Hi, How Are You T-shirt worn by Kurt Cobain in the early

’90s.

Regardless

of how he’s positioned, Johnston was indisputably working well outside the

bounds of conventional art knowledge, honing a singular style of drawing that

melded comic book illustration with feverish sketching. He worshipped at the

altar of John Lennon and Jack Kirby, using their twin examples to forge his own

kind of psychedelic art. “There are a lot of clichés we think of relative to

’60s and ’70s hippie expressions; Daniel’s work is not full of those clichés,”

Gary Panter tells me via email. “He invented his own colorful route through the

angels and demons of his inner life.”

Like the

silent, self-taught artist Susan Te Kahurangi King and the janitor-by-day,

visionary painter-by-night Henry Darger, Johnston took familiar iconography from

pop culture and imbued it with his own passions, anxieties, and deep wells of

religious feeling. Recognizable characters like the Hulk, the Beatles, and

Casper the Friendly Ghost run up against imagined creatures in confrontations

that range from bizarrely funny to deeply disturbing. “Oh Lord Please Don’t Let

Me Be Misunderstood” (2002) finds Captain America on the run from a scourge of

winged eyeballs, while “Eternal Punishment!” (1985) depicts Casper flying over

the tormented in hell, vengefully exclaiming “it is here, you’ll wait for

eternal punishment!”

Many

drawings are zany and packed with flashes of imaginative color. But when the

currents of Johnston’s anxiety crossed wires with his sexuality, the results

could be downright ominous. “My Nightmares” (1980) features a screaming demon

head with a curiously phallic body looming over a sleeping Johnston, while

“Untitled Torsos & Devils” (1995) depicts an impish Satan watching an army

of women’s torsos on parade. Even in these instances, though, his descents into

hell are offset by goofy comic touches. The sinister-looking “Great King Rat”

(1980) gets knocked down a peg when you notice his skinny legs and flip-flops,

and Casper eventually flies up to heaven in the sweetly triumphant “Here We Go,

Mary!” (1982).

As a

curator, Panter’s process was fairly straightforward: “I chose my favorites

from a whole lot of drawings and then tried to choose drawings that were

compatible with each other, and also drawings that as a group showed the range

of returning characters and motifs he used.” This approach succeeds in

highlighting the hallmarks of Johnston’s style and his major emotional themes,

but it also underscores the show’s minor weakness. Without offering more

context for some of Johnston’s recurrent images (including the complex

symbolism of his eyeballs), it might be difficult for the casual viewer to

unpack all of this art’s riches, its coded meanings and evolutions.

The

exhibition is, however, loaded with Easter eggs for fans of his music.

“Speeding Motorcycle” (1984), which shares its title with a track from Yip/Jump

Music that plays on loop in Electric Lady, looks like his music sounds,

triggering a latent synesthesia that throws the rest of his work into sharp

relief. The nursery simplicity and relentlessness of his recording has a clear

counterpart in his drawing hand, where pens, markers, and expressionistic

shading are deployed to similarly immediate, strangely beautiful effect.

If

Daniel Johnston’s music is gripping for how achingly direct it feels, the

revelations contained in his drawings stem from his willingness to dramatize

the contradictions that many of us have repressed or forcefully resolved to

more easily navigate the world. The quiet certainties of a conventional life

find a counterpoint in Johnston’s fiery, boundless imagination, the engine that

allowed him to create so prolifically. The lack of irony or knowingness feels

like generosity rather than frailty, a disarming reminder of what is most

meaningful about art, music, and life.

What

Daniel Johnston’s Drawings Mean Now. By Harry Tafoya. Pitchfork, February 3, 2021.

When

Daniel Johnston passed away in late 2019, his absence was felt not just by

music fans, but also those in the visual arts. He had been garnering a

following for his cartoon-like vibrant drawings—mostly made with markers and

pencil on standard printer paper—since he began his music career in Austin,

Texas in the 1980s. He was as prolific with his drawings as he was writing his

haunting, unfeigned music, eventually taking part in the 2006 Whitney Biennial.

This year, Johnston’s drawings are getting their own dedicated show at Electric

Lady Studios, on view from January 28 through February 7, as part of the

Outsider Art Fair in New York City. GARAGE reached out to Gary Panter, who

curated the show and whose own work is similarly rooted in the comic

book-superhero-aesthetic, to learn more about how Johnston’s work fits into the

outsider art oeuvre.

So tell

me about your relationship to Daniel Johnston and to his work. How did he

become a part of your life?

I only

know Daniel’s work through media. I have friends who worked with him—Kramer, Jad

Fair, and others who had brushes with him or his work. It was hard to miss his

work when it surfaced in rock magazines

and LP covers. It is very energetic, compelling and colorful work with a strong

psychic charge.

Did he

ever influence your work?

No. I am

older than Daniel. I admire his work as

a drawer and colorist and storyteller. There are people like Darger, Susan King

and Daniel whose work I see in media and feel a closeness to—that we were

working on related issues as drawers and image experiencers. So I recognize

them as some kind of comrades at a remove.

Was it a

powerful experience to see all of this work grouped together?

I was

trying to cover the repeating themes to show a kind of hieroglyphic aspect of

his work.

So I

wanted to get Captain America and Thor, Jesus, and Satan, the reoccurring

ducks, nudes, and monsters all in and the ones with the nicest shapes on the

page.

I would

say that Daniel’s work is very confident, emphatic, colorful. Obsessive,

loosely organized, pleasing, somewhat distressing. That it seems to try to

clarity confusions but maybe only produces psychic explosions. Like his music

it combined innocent hopefulness and melancholy. At first glance one might not

sense mental distress because the work was produced in an energetic manic mode.

It seems

like you and Daniel had several experiences in common—especially as they relate

to Christianity and acid trips. Does that make you feel a special connection to

him?

We are

both from the Church of Christ and subjected to the consequence of that. And

both subjected ourselves to psychedelic drug experiences. Both of those things

are pretty heavy. I am somewhat damaged from fundamentalist church in Texas and

poison LSD, but I guess that adversity is a kind of gift, as artists seem to

need a puzzle, or compelling problem, irritant, or emotional hunger of some

kind to work with. Texas is a thing in itself, as an issue of a state of mind

where there is great pressure to conform. Daniel had other issues that hurt and

inspired him. I am happy to not do Darger, or King or Daniel Johnson’s, work.

My insight into their work, if I have any, is from being a life long

art-obsessed person who must make things. And from the temporary psychosis I

experienced on difficult trips. The concepts, conundrums, vicious circles,

rhetorical devices, and traditions pretzeling the assertions of the historians

and institutionalists of primitive Christianity are enough to drive one crazy

or at least get you out of Texas. As bad as bad acid. I do love Texas. It is a

cauldron of primal forces.

Of

Satan, Captain America, and Daniel Johnston. By Annie Armstrong. Garage ,

January 22, 2021.

If you don’t

know Daniel Johnston’s music :

On Daily Motion is Jeff Feuerzeig's award-winning 2005 documentary The Devil and Daniel

Johnston. With Spanish subtitles.

No comments:

Post a Comment