Set in high-society England of 1813, the bodice-ripping show has attracted record audiences for Netflix – 82 million households streamed it in its first month on air – making it the network's biggest series debut. Bridgerton has even spawned its own buzzword, "Regencycore": think sumptuous dresses, satin elbow-length gloves, pearl-encrusted headbands and, of course, corsets – vital to the eye-catching decolletages that feature prominently in the show.

Corsets are in focus from the first episode of the series. In one comical scene, Prudence, the eldest daughter of social-climbing Lady Featherington, is being "tight-laced" into a corset by a maid to be slimmer for her presentation to Queen Charlotte. The laces are yanked until she can barely breathe, as her unsympathetic mother looks on, saying that when she was Prudence's age, her waist had been "the size of an orange and a half".

Fashion experts have since pointed out that liberties may have been taken with historical facts – that being whippet thin wasn't in vogue at the time, and the empire-line dresses of the day flowed freely below the bust. "A corset of the Bridgerton era would typically have been high-waisted not waist-pinching," Valerie Steele, director of the museum at New York's Fashion Institute of Technology, tells BBC Culture. But she concedes that tight-lacing does "look good on film".

The corset scene does drive home a truth – that women such as the unmarried Bridgertons and Featheringtons did what they had to (or were told to), when "climbing socially and marrying well" was their best chance of improving their lot. "A blossoming of the bosom," was the effect costume designer, Ellen Mirojnick, sought to create for the Bridgerton's female cast, from the young lead, Daphne, to the more mature Lady Danbury.

"That was the emphasis of the woman's body at the time, your eye went directly to the top of her décolletage," says Mirojnick. In creating the "1813 silhouette", the corsets were key. For the job, they hired Mr Pearl, whose name is sacrosanct in corsetry. On hearing she had him on her team of more than 200 artisans, Mirojnick says she "almost fainted. It was a gift from the gods. [Mr Pearl] is the foremost corset maker in the world today".

Mr Pearl (born Mark Erskine-Pullin) has worked with UK performance artist Leigh Bowery at London's Royal Opera House, and with fashion designer Thierry Mugler. He also made Kylie Minogue's dazzling corset costume from a John Galliano design for her 2006 Showgirl tour.

One of his high-profile clients is burlesque performer Dita von Teese, who wore a Mr Pearl corset under her Vivienne Westwood gown when she got married in 2005. A corset connoisseur of 30 years' standing, Von Teese has her own lingerie line and works with Dark Garden, founded in 1989 by Autumn Adamme; the company, based in San Francisco, produce the Dita, a 10-panelled corset named after her.

Von Teese has conceded the garment is not for everyone, saying it is a bit like high-heel wearing – "it's not necessarily easy". However, a bespoke model will nearly always be more comfortable than one bought off the rack as" our bodies are all shaped differently and the places where we want to be compressed can change". In recent years the notion of waist-training, the practice of using a corset or elasticated belt with the aim of modifying the body shape, has gained popularity. But Von Teese says in her experience it is not possible to permanently alter your shape in this way.

While there is evidence of corset-like garments being used in the Minoan culture and Bronze Age ancient Crete, the first corset is said to have originated in the 16th Century, initially in Italy, then in France, introduced by Catherine de Medici. In Elizabethan times, the corset moulded the torso into a cylindrical shape rather than the hourglass shape that was sought after by Victorians. Early corsets stiffened with metal, ivory or whalebone no doubt contributed to an enduring belief that the garment is health-threatening, or even an instrument of torture.

Karolina Laskowska is a British lingerie designer who has been creating hand-made corsets since 2012. Her bespoke pieces cost from £1,000 – but they do involve more than 100 hours' work each. She dismisses the idea of the corset as a torture instrument as "a lazy trope – one that harks back to men deciding what women should and shouldn't wear". She refers to Dr Warner who "decided corsets were bad for women, and invented his own 'health corset' [1873], to give women the 'perfect' shape – and made him a fortune by doing so." In her opinion, a well-fitting corset can "take the strain off the shoulders and ribcage, thus being more comfortable than a bra. In fact I've had clients say putting on a bespoke corset feels like having a wonderful hug."

While researching her book The Corset: A Cultural History, Valerie Steele worked with a doctor "to try to figure out to what extent the corset could have caused disease. But [we concluded] it didn't cause curvature of the spine, in fact it has often helped to correct it. Perhaps a few women fainted, or felt the fabric chafed their skin, but the corset didn't cause your liver to be split in two or the many things it's been blamed for".

Among the most memorable corset "moments" of the past 100 years are Horst P Horst's famous photograph Mainbocher Corset, Paris in 1939; Sophia Loren's black satin hourglass number in The Millionaire, 1960 and the more recent Wonder Woman 1984, with its moulded metal corset-armour. All have attracted criticism as well as appreciation. Decades after the release of Gone with the Wind, US feminist writer Gloria Steinem described Scarlett O'Hara being laced into a corset to achieve a 17-in waist in order to seduce Ashley as a "perfect illustration of female bondage, Southern style".

Steele has heard the disempowering argument many times but says "It's a mistake to patronise women, to suggest they were all stupid victims for, say 400 years," she says. Laskowska agrees: "A corset can be a beautiful thing you wear just for yourself, not for any man. I do that, and I feel empowered by it."

While the corset can today be seen as "a sexy, kind of cheeky garment," adds Steele, "for four centuries to wear one was to be respectable and conformist – to be 'straight-laced' was literally to be upstanding". The turning point came in the 1970s and punk fashion led by Vivienne Westwood, "when corsets came back, initially as a fetish-style garment, one that was rebellious and highly sexualised," says Steele. It carried through with Madonna in conical-breasted corsets by Jean-Paul Gaultier on her 1990 Blonde Ambition tour, "when she seemed to say 'I'm not oppressed, I'm a sexually liberated woman'".

Westwood's corset designs may be "one of her most important contributions to 20th-Century fashion" according to Steele. They are indeed highly prized collectors' items: her corset design printed with a detail from the 1743 François Boucher painting Daphnis and Chloe resides in the V&A. Fans of her Boucher corsets include the model Bella Hadid, and pop stars Miley Cyrus and FKA Twigs. Twigs modelled some of her extensive vintage Westwood collection for her digital zine Avantgarden.

As a second series of Bridgerton prepares to start filming in the spring, Mirojnick reflects on the role the show is playing for an ever-growing audience: "It allows our imagination to flourish – and transports you into a place that's fun to watch, especially given the bleak times we're living in." Corsets and all.

The controversial garment that never goes out of fashion. By Beverley D'Silva

BBC, February 18, 2021

“I was able to squeeze my waist into the size of an orange-and-a-half when I was Prudence’s age,” Lady Featherington says.

Many movies, historical as well as fantastical, have a similar scene. Think of Gone With the Wind’s Scarlett O’Hara death-gripping a bedpost; Elizabeth Swann in Pirates of the Caribbean laced so tightly into her corset that she can barely breathe; Titanic’s Rose in a nearly identical scene; Emma Watson, playing Belle in Disney’s live-action remake of Beauty and the Beast, declaring that her character is too independent to wear a corset.

One other element shared by some of these scenes, among many others? None of the characters suffering through the pain have control over their own lives; in each scene, an authority figure (Prudence’s and Rose’s mothers, Elizabeth’s father) tells them what they must do. It’s a pretty on-the-nose metaphor, says Alden O’Brien, the curator of costume and textiles at the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum in Washington, D.C.

“To have a scene in which they’re saying, ‘tighter, tighter,’ it’s obviously a stand-in for … women’s restricted roles in society,” O’Brien says.

The trouble is that nearly all of these depictions are exaggerated, or just plain wrong. This is not to say “Bridgerton” showrunner Shonda Rhimes erred in her portrayal of women’s rights during the early 19th-century Regency era—they were indeed severely restricted, but their undergarments weren’t to blame.

“It’s less about the corset and more about the psychology of the scene,” says Kass McGann, a clothing historian who has consulted for museums, TV shows and theater productions around the world and who founded and owns the blog/historical costuming shop Reconstructing History, in an email.

Over four centuries of uncountable changes in fashion, women’s undergarments went through wide variations in name, style and shape. But for those whose understanding of costume dramas comes solely from shows and movies like “Bridgerton,” these different garments are all just lumped together erroneously as corsets.

If one does define a corset as “a structured undergarment for a woman’s torso,” says Hilary Davidson, a dress historian and the author of Dress in the Age of Jane Austen, the first corsets appeared in the 16th century in response to women’s fashion becoming stiffer and more “geometric.” The corset, stiffened with whalebone, reeds or even sometimes wood, did somewhat shape women’s bodies into the inverted cone shape that was in fashion, but women weren’t necessarily pulling their corsets tight enough to achieve that shape. Instead, they used pads or hoops to give themselves a wider shape below the waist (kind of like Elizabethan-era booty pads), which, in turn, made the waist look narrower.

This shape more or less persisted until the Regency era of the early 1800s, when there was “all sorts of invention and change and messing about” with fashion, Davidson says. During that 20-year period, women had options: They could wear stays, boned, structured garments that most resemble today’s conception of a corset; jumps, very soft, quilted, but still supportive undergarments; or corsets, which were somewhere in between. O’Brien says the corsets of the Regency period were made of soft cotton (“imagine blue jeans, and turn them white”) with stiffer cotton cording for support, and occasionally channels in the back for boning, and a slot in the front for a metal or wooden support called a busk. (Remember, though, these supports were made to fit an individual’s body and would gently hug her curves.) Eventually, the term corset (from the French for “little body”) is the one that won out in English, and the shape gelled into the hourglass shape we think of today.

But all along, these undergarments were just “normal pieces of clothing,” Davidson says. Women would have a range, just like today’s women “have a spectrum of possibilities, from the sports bra to the Wonderbra.” Those simply hanging around the house would wear their more comfortable corsets, while others going to a ball might “wear something that gives a nicer line.” Even working women would wear some sort of laced, supportive garment like these—giving lie to the idea that putting on a corset immediately induced faintness. For Davidson, the myth that women “walked around in these uncomfortable things that they couldn’t take off, because patriarchy,” truly rankles. “And they put up with it for 400 years? Women are not that stupid,” she says.

These garments were comfortable, Davidson adds, not just by the standards of the time—women started wearing some sort of supportive bodiced garment when they were young girls, so they were accustomed to them by adulthood—but by modern standards as well. O’Brien concurs: “To have something that goes further down your bust … I’d really like to have that, because it would do a better job of distributing the support.”

By the Victorian period, after “Bridgerton,” corsets had evolved to a more hourglass shape—the shape many people imagine when they think of an uncomfortable, organ-squishing, body-deforming corset. But again, modern perceptions of the past shape how we think of these undergarments. Davidson says skirts were bigger during this time—“the wider the skirt, the smaller the waist looks.” Museums often display corsets in their collections on mannequins as if their edges meet. In reality, they would likely have been worn with their edges an inch or two apart, or even looser, if a woman chose.

McGann suggests that one of the reasons corsets are associated with pain is because actresses talk about their discomfort wearing an uncomfortable corset for a role. “In many cases, the corsets are not made for the actress but rather a corset in her general size is used for expediency,” McGann says. “This means they are wearing corsets that don't fit them properly, and when laced tightly, that can hurt!”

So, in the Regency era and in other periods, did women tighten the laces of their corsets beyond what was comfortable—or healthy—in service of achieving a more fashionably narrow waist? Sure, some did, when they had someone to impress (and in fact, Davidson gives the Gone With the Wind corset scene high marks for accuracy, since Scarlett O’Hara is young, unmarried, and trying to make an impression). In “Bridgerton,” social striver Lady Featherington’s insistence on her daughters’ narrow waists similarly seems logical. Except…in the Regency period, where dresses fall from the bust, what would be the point of having a narrow waist? “The whole idea of tightlacing is completely pointless…irrelevant for the fashion,” Davidson says.

“There is no way that period corset is going to [narrow her waist], and it’s not trying to do that,” O’Brien adds.

Davidson has another quibble with the undergarment fashion choices of “Bridgerton” (at least the first episode, which she watched at Smithsonian magazine’s request). Corsets and stays of the Regency period were designed less to create the cleavage that modern audiences find attractive, and more to lift up and separate the breasts like “two round globes,” Davidson says. She finds the corsets in “Bridgerton” too flat in the front.

In an interview with Vogue, “Bridgerton” costume designer Ellen Mirojnick laid out her philosophy on the series' apparel: “This show is sexy, fun and far more accessible than your average, restrained period drama, and it’s important for the openness of the necklines to reflect that. When you go into a close-up, there’s so much skin. It exudes beauty.” But, Davidson says, “while they sought sexiness and cleavage and maximum exposure, the way they’ve cut the garments actually flattens everyone’s busts. If they’d gone back to the Regency [style of corset] you would have gotten a whole lot more bosom. You would have had boobs for days.”

“Bridgerton” does, however, get a lot right about the status of women in the early-19th century. Marriage was one of the only options for women who didn’t want to reside with their relatives for the rest of their lives, so the series’ focus on making “good matches” in matrimony holds true. Once wed, a married woman legally became her husband’s property. She couldn’t sign contracts or write a will without her husband’s consent.

By the mid-19th century, women had made significant gains in being able to own property or obtain a divorce. It wouldn’t be until 1918 in England or 1920 in the United States, however, that (some) women could vote. Around the same time, corsets were falling out of fashion, and many writers of the time saw a connection between liberation from the corset and women’s liberation.

O’Brien says that looking back now, that conclusion doesn’t hold up. “You have all these writers saying, ‘Oh, we’re so much more liberated than those dreadful, hypocritical, repressed Victorians, and we’ve thrown away the corset.’ Well, I’m sorry, but if you look at shapewear in the 1920s, they’re doing the exact same thing, which is using undergarments to create the current fashionable shape,” which in the Roaring Twenties meant using “elasticized” girdles and bust-binders to “completely clamp down on a woman’s natural shape.

“Society always has a body ideal that will be impossible for many women to reach, and every woman will choose how far to go in the pursuit of that ideal, and there will always be a few who take it to a life-threatening extreme,” O’Brien adds

O’Brien and Davidson hope people stop thinking of corsets as oppressive tools of the patriarchy, or as painful reminders of women’s obsession with fashion. That attitude “takes away female agency,” O’Brien says. “We’re allowing fashion’s whims to act upon us, rather than choosing to do something.”

Wearing a corset was “as oppressive as wearing a bra, and who forces people into a bra in the morning?” (Some women in 2021, after months of Zoom meetings and teleworking, may be asking themselves that exact question right now.) “We all make individual choices,” Davidson says, “about how much we modify ourselves and our body to fit within the social groups in which we live.”

It’s easier to think of corsets as “strange and unusual and in the past,” Davidson says. To think of a corset as an oppressive tool of the past patriarchy implies that we modern women are more enlightened. But, Davidson adds, “We don’t wear corsets because we’ve internalized them. You can now wear whatever you like, but why does all the Internet advertising say ‘8 weird tricks to a slim waist’? We do Pilates. Wearing a corset is much less sweat and effort than going to Pilates.”

What ‘Bridgerton’ Gets Wrong About Corsets. By Rachel Kaufman. Smithsonian Mag, January 8, 2021.

The origin of the corset mainly derives from Western society during the 15th century, although corset-like garments date back to the Minoan civilization in ancient Greece.

During the Renaissance era, Catherine de’ Medici influenced corseted fashion by banning “thick waists” within her court. The elite women of Western society frequently wore these stiffened garments to attain a slender waist, with lacing from both the back and front and a “stomacher” to conceal these laces. Rather than mask these corsets under layers of fabric, Renaissance fashion showcased these decorative, structural adornments cinching womens’ figures. In the end, this era of “rebirth” defined this continual desire for a slimmer stature, including the eventual hourglass figure of the 1800s and the “S-bend” silhoutte of the 1900s.

Despite its controversial history of restraining the female body, the corset remains a prominent garment within fashion. Here, V recalls the evolution of the corset throughout 20th century fashion into modern day society.

Corsets of the Edwardian Era formed an “S-bend” curve to achieve this puffed-out demeanor, often referred to as the “Porter Pigeon.” The straight-front and curved backside of both long and short bodices emphasized the proportions of the female body, creating an arched back and enhanced monobosoms.

Skilled corsètieres were in high demand during the early 20th century as idealized fashion attire became publicized through postcards and cigarette cards. Actors and other refined female figures were depicted on these commercial outlets, illustrating the fashion trends of that era. The Gibson Girl was the most notable portayal of this ideal womanhood, and signified “The New Woman” through her tiny waist and elongated figure.

During the First World War (1914-1918), women who entered the workforce shifted the fashion trend of contouring the female body to supporting it instead. This latest progression in women’s fashion remained a favored design entering the 1920s, signaling the change for a more active lifestyle. With the introduction of elastic, sports corsets provided women mobility through looser construction and flexibility.

The La Garçonne look became well-renowned postwar, emphasizing a boyish, pre-pubescent style that required a more column-like figure. Corsets in the 1920s were designed to slim the hips and create this youthful stature; the additions of garters were included to attach stockings. Flapper girls in particular needed this freedom of movement to dance, so corsetry veered towards cylindrical, elastic corsets to support this latest activity.

The desirability for a fitted, slender silhouette emerged during the 1930s. While women still exhibited slimmer hips from the previous decade, their waistlines were enhanced with laced and featherlight boned corsets. Beauty became associated with health, leading to this figure-hugging bodice seen within corsets and shaped brassieres; a shapely frame alluded to a robust physique.

With the Great Depression and World War II, utilitarian attire stressed the need for boxier cuts and hanging silhouettes during this period of repression. However, those who rejected this modernistic fashion turned towards neo-Victorianism. This aesthetic favored ornamentation and extravagance, and often provided audiences a form of escapism during the Great Depression. Period pieces in the '30s such as Gone with the Wind and Little Women depicted these elegant gowns and corseted imagery, while designers such as Norman Hartnell fabricated ensembles with thin, modeled waistlines (i.e. Neo-Georgian Ball Gown).

Following World War II, utilitarian undergarments were gradually superseded by delicate designs that exuded femininity. This was especially featured in Christian Dior’s “New Look” in 1947. A billowed skirt and cinched waist were emphasized within his haute couture collection, returning to a period of finesse.

The introduction of nylon in fashion provided a more light-weight, constructed bodice that became known as the girdle. The girdle was often made of nylon and latex rubber, and offered women a flattened posterior in comparison to the corset. Many women still wore constricted waspies, consisting of a boned bodice fastened by lace and/or hooks that narrowed down the female waistline. While these women retained the more restricting components of traditional corsets, younger generations usually preferred the girdle’s structure. Conical cups were an additional feature used for girdles and brassieres, achieving this pointed breast shape that was epitomized in the ‘50s.

Fashion witnessed the gradual decline of corsets as sporty, healthier lifestyles became prominent during the 1960s and 1970s. Rather than confine their figures underneath tight-fitting garments, women often focused on their diet and exercise regimens to acquire this silhouette.

With the emergence of the punk aesthetic, however, designers resurrected the corset during this contemporary revival of Victorian-esque styles. Acclaimed fashion designers such as Vivienne Westwood and Jean Paul Gaultier experimented with corseted silhouettes during the 1970s and 1980s. As an aficionado of historical punk, Westwood re-interpreted the corset as a symbol of empowerment rather than the suppression of women. In regards to Gaultier, his pink satin corset worn by Madonna circa 1990 is perceived as one of the most iconic designs in fashion.

Yves Saint Laurent, Tom Ford, and Thierry Mugler also incorporated corseted designs into multiple collections throughout these decades, most of which led to the trend of underwear as outerwear.

Celebrities and fashion influencers have also integrated corsets into their street style, including Bella Hadid, Kim Kardashian, and Rihanna. This iconic garment of feminine sexuality is still a traditional component within the history of fashion.

From Then ‘Til Now : History of the Corset. By Michaela Zee. V Magazine, March 19, 2020.

From Jean Paul Gaultier, Thierry Mugler and Vivienne

Westwood to Sinéad O’Dwyer, we chart the history of fashion’s most

controversial garment.

It’s 48 hours before the Met Gala and Kim Kardashian-West is being strapped into the final fitting of her Thierry Mugler wet-look dress. And I’m using “strapped in” quite literally, here. As she speaks to Vogue’s cameras about the inspiration behind the look (“[Mugler] is, like, the king of camp”), she’s being laced into a corset by three -- count them, three -- people. And she looks visibly uncomfortable -- eyes glazing over a little bit, letting out vocalized sighs, you can see her mind buffering as she speaks, she’s leaving ellipses between words. “If I don’t sit down for dinner, now you know why,” she tells Vogue, leaning crookedly against the edge of a chair. “I’ll be walking around mingling, talking, but I can hardly sit”. Two months after the gala, WSJ Magazine asked Kim about the infamous wasp-waisted dress. “I’ve never felt pain like that in my entire life,” she answered.

“The corset is probably the most controversial garment in the entire history of fashion,” writes fashion historian -- and the world’s foremost corset scholar -- Valerie Steele in The Corset: A Cultural History. The garment -- a rigid bodice that’s laced to shape the torso -- has a tumultuous legacy, to say the least. Perhaps the most polysemous garment of all time, the corset is both adornment and armour, it elicits desire, signifies restraint and performs fashion’s greatest magic trick, the transformation of the body; it’s been both sculpting and forming itself to female ideals of beauty since the 1500s. Throughout its history, the corset has been reviled as an “instrument of torture” by 16th century doctors and 20th century feminists alike (and many in between), for the ways it’s deformed the body and impeded upon women’s personal freedoms. Despite this, the garment has emerged as one of spring/summer 20’s most ubiquitous trends. Why?

The corset, as we know it now, emerged in the 1500s, though iterations -- made from soft canvas and iron, even -- date back to antiquity. These 16th century corsets, also known as “stays,” are the familiar boned bodices seen in a Shakespeare adaption or, perhaps, a Keira Knightley costume drama, laced up the back, and crafted from rigid materials like horn, buckram and most famously, whalesbone. Discipline -- both mental and physical -- was a virtue to members of the era’s European elite; bodily control manifested in the form of the corset, which was worn by women (and some men) to hold the body erect, to improve posture but also, to posture. To the nobility, corsets were meant to be constricting: after all, their class valued self-control above all.

Most evidently, women wore corsets to meet the beauty standards du jour. In the 16th century, the look was an elongated, conical torso, with the stays extending to the hips. The 1700s favored short, hourglass silhouettes. And in the 19th century, tight bodices pushed the breasts up and out, to form an S-shape. The common denominator was a small, pinched waist. And women suffered for it. The stylish Georgiana Duchess of Devonshire described the discomfort of a corset in the 1778 novel The Sylph: “my poor arms are absolutely sore with them; and my sides so pinched! But it is the ‘ton’; and pride feels no pain.” In the same century, poet Elizabeth Ham referred to them as “very nearly purgatory.” It’s true that corsets deformed the ribs and misaligned the spines of their wearers. In the 16th century, surgeons alleged that stays could cause respiratory disease, suffocation and sudden death. And while these claims, along with myths of women having ribs surgically removed to achieve a thinner waist, are false, even moderately tight corsets restrict respiration, leading to palpitations, shortness of breath and fainting.

Not surprisingly, advancements in women’s emancipation lead to the undergarment’s demise. French couturier -- and famous corset hater -- Paul Poiret proclaimed the fall of the corset (in the name of Liberty) at the beginning of the 20th century. By the event of World War I, as women entered the workforce, the garment fell out of favour, for good. Well, almost.

In 1987, British designer Vivienne Westwood revived and revolutionized the corset, turning the garment inside out -- literally. In true Westwood parody, the anarchical designer’s autumn/winter 87 “Harris Tweed” collection poked fun at the frumpy prudishness of British nobility, transforming their stuffy, traditional textiles (Harris Tweed) and garments (corsets) into glamorous garb. Westwood named the collection’s corsets -- which would become her signature piece -- the “Stature of Liberty,” and liberating they were. Unlike the body-modifying, rib-crushing bodices of yore, Westwood’s confections were purely decorative in nature, constructed with lycra panels and zippered backs. They raised the bosom, but let the wearer breathe. More importantly, they were the first corsets to be worn as outerwear. Suddenly, what was once a symbol of female oppression became the uniform of third-wave feminism, a cheeky symbol of women embracing and owning their sexuality. Of the corsets, the designer told L’Officiel, “[They look] great flat-chested or with your dumplings boiling over.”

The corset, for Madonna, was a similar type of power move. On the first night of her 1990 Blond Ambition tour, during the concert’s opening number, the singer ripped open a zoot-y pinstriped blazer to reveal that cone-breasted satin corset -- you know the one. It was a move that echoed, cementing Madonna’s legacy as the foremost pop star, and as a pop culture icon. But how did one garment cause such a shockwave? Unlike Dame Westwood’s busty designs, the Jean Paul Gaultier-designed bodice weaponized the female form, transforming its sinuous curves into spikes that seemed to prick. The look was assertive, intimidating; it symbolized a woman in complete control of her sexuality, and dominant, even. Wearing the JPG corset (over a pair of pants, I might add), Madge danced, simulated masturbation, and thrusted her hips as she sang, “You’ve got to make him express himself.”

By the time the mid-90s rolled around, the corset had taken over the runways of Europe. Think early John Galliano, famous for his history-plundering designs, who used the corset to tell the lush, fantastical fashion narratives that would define his career. The British designer’s spring/summer 93 collection, titled “Olivia the Filibuster”, told a tale of shipwrecked swashbucklers; models swaggered and swayed down the catwalk in corseted leather jackets and striped bustiers. For his autumn/winter 93 collection, about a runaway 19th century Russian princess, Galliano sent Kate Moss tearing down the runway in a billowing hooped skirt and corset to match.

And, of course, think Mugler. What was the 20th century corset renaissance without the king of camp, the master of catwalk showmanship, French couturier Thierry Mugler? He’s responsible for not only some of the 90s most iconic runway moments, but some of the most audacious looks of all time. And nowhere is this embodied more, perhaps, than look 101 of his autumn/winter 95 couture spectacular. Like an Arthurian knight from the future (or a cyborg from the past), German super Nadja Auermann stepped out in a golden hard-bodied corset dripped in rhinestones, and with matching articulated sleeves. And although the legendary designer officially retired in 2002, his extreme designs -- and extreme corsets -- live on into the now, under the creative directorship of Casey Caddawaller. The newly-appointed Mugler designer has resurrected his predecessor’s predilection for the waist-snatching garment into some of the zeitgeist’s most memorable fashion moments. Bella Hadid opened the house’s spring/summer 20 show in one of the season’s sexiest and most viral looks: a mesh corset, styled with a teensy blazer and no pants.

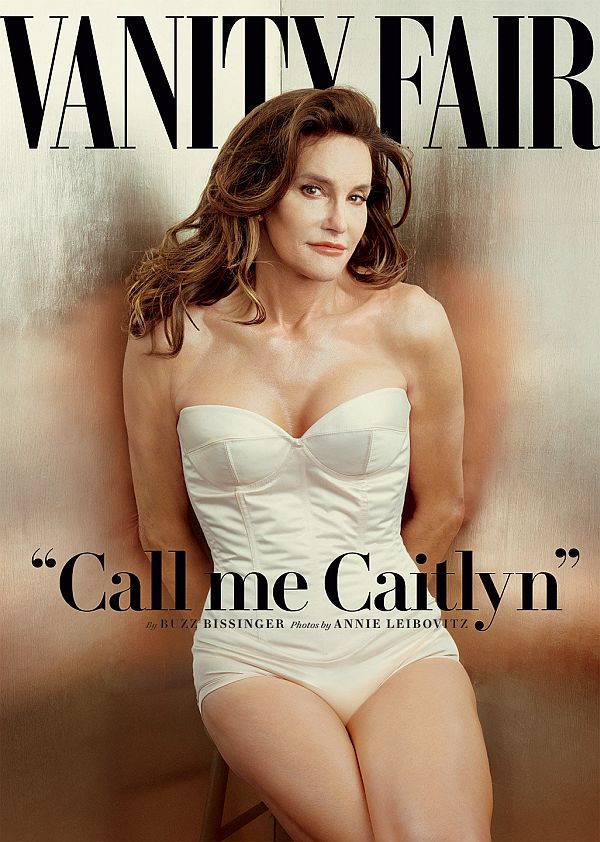

Perhaps more subversive a statement than even Madonna’s Gaultier cone bra, the 21st century’s most iconic corset moment arrived on June 1, 2015. Caitlyn Jenner appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair, in true covergirl fashion, mane tousled, head coyly cocked to the side, and wearing a sumptuous silk satin bodice. The look was an ode to the pin-ups of yore -- namely Playboy’s first cover star, Marilyn Monroe, herself -- and a powerful way for the trans trailblazer to claim space and express her new gender identity.

But no one living today knows the corset as intimately as Keira Knightley. The actress, herself, has become synonymous with the period drama, the type of historical film in which you might spot a stay or two. The genre, itself, is both the largest proponent and detractor of the corset. Think Kirsten Dunst in Sophia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette, her cleavage iced, like one of her three-tier cakes, in pale yellow silk, pink ribbons, and ruffles and ruffles of lace. Likewise, seeing Glenn Close’s buoyant boobs in Dangerous Liaisons might make us want to strap into one of the near-lethal undergarments, ourselves. Nearly -- because what’s a great period drama without a boudoir scene to shatter the illusion. Who can forget the image of Viven Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara, elbows around a bedpost, being laced into her stays. Or Knightley as Elizabeth Swann, gasping, as two chamber maids tighten her laces. A few scenes later, out of breath and feeling faint, she plummets from a castle turret into the gnashing sea below. Knightley has donned a corset on the sets of nine different films. A corset connoisseur, her review of the garment: “positively awful.”

While many credit Prada’s autumn/winter 16 collection -- its centerpiece a half-laced white canvas body -- for the most recent resurgence of the garment, it was Sydney-based indie label Daisy who ushered in the corset’s most recent renaissance. A millennial riff on the milkmaid fantasy, the mark’s spring/summer 15, “Pure Country” collection, offered a selection of broderie anglaise dresses, laced from sweetheart-neckline to hem, alongside leather underbust corsets and other down-home-hot bustiers, printed in gingham or crafted from calf-hair. The look, according to the label, was everyday eroticism, a bubbly, quotidian sexy that demonstrated the quintessential it girl fit could transcend ripped jeans and a band T-shirt. The movement went viral, with the zeitgeist’s batch of Insta-girls -- from Kendall Jenner and Bella Hadid to Petra Collins -- decked in corseted, micro-mini prairie dresses, all laced loosely, effortlessly up the front.

The corset disappeared from women’s wardrobes in the 20th century, but the ideals it spawned -- damaging or not -- live on. In place of a boned bodice, women have internalized the corset through diet, exercise, cosmetic surgery, digital retouching, flat tummy tea. The list goes on. It’s really no surprise that into the 2010s, the corset -- in its true, functional form -- has made a return. In the era of instant gratification -- movies and music at a single click, the ability to transform your (digital) body with a few flicks of the Facetune app -- why wait for the months-long pay off of a workout regiment? Emblems of this Insta-era, the Kardashians began peddling waist trainers -- corset-like devices that promise to whittle the waist to a perfect hourglass -- as far back as 2014. Since then, health experts have cautioned against the harmful garment, which, at best, rests on unfounded claims and, at worst, causes long-term structural issues. Despite these warnings, the trend has blown up: one model of the waist-shaper has over 3,000 reviews on Amazon. Ironically (or not), the product’s copy leads with the question “Want a sexy figure like Kim Kardashian?”

Two new labels that are bringing corsets back for SS20 are Australian mark all is a gentle spring and Brooklyn designer Kristin Mallison. Following in the footsteps of Daisy, both brands approach the body-cinching piece with a whimsical nostalgia. all is a gentle spring’s signature pastoral corset is printed in a Toile de Jouy pattern, which depicts idyllic scenes from the era of the garment itself. Same goes for Mallison and her viral iterations, pieced together from vintage tapestries and upholstery fabrics, embroidered with elaborate tableaux of 18th century courtship and folly. Both labels, who gained their followings equally through affiliations with already-iconic boutique Café Forgot and the power of social media, have brought the antiquated garment into the digital age, where it thrives. Instagram is all about the flex and the fantasy, and the corset -- with its extreme look -- brings it, on both fronts.

To some new designers, the corset can be a means of protection, against the barbs of the world’s current political climate. The duo behind British label Charlotte Knowles titled their SS20 collection “Venom”; it’s an offering of what they call “militarized corsetry.” Instead of laces and eyelets, Knowles’ bodies fasten with Velcro and press-studs, like tactical vests; traditional whalesbone and steel rods are replaced with flexible silicone, for combat-ready ease of movement. “Our woman is fighting for her place in the world,” Knowles’ designer partner Alexandre Arsenault told Vogue, “She is tough and dangerous.” Similarly, fellow Londonite Dilara Findikoglu -- known for her goth-y, historical garb -- dressed Madonna in what she called an ‘armour corset’, in the style of Joan of Arc, for Madge’s 2019 Eurovision performance. After all, a corset’s not that far off from a breastplate.

Of all the designers reviving the corset this season, none are doing it quite like Sinéad O’Dwyer. Cast in silicone, moulded from lifecasts of her muses and friends, O’Dwyer’s bodices actually share very little in common with the traditional garment, save for lacing, the focus on the female form. Whereas historic corsets were meant to eradicate the ‘natural’ body, O’Dwyer embraces it -- sagging breasts, cellulite, ‘fupa’ and all. Her designs are a response to today’s narrow ideals of beauty, the very ones that have been shaped by the corset since the 1500s; they’re about opening up a space within fashion for all body shapes and sizes. “My work is a sort of ‘fuck you’, and a declaration of pride in your body. I think it conveys the power that comes from women deciding that they don’t have to accept the status quo,” she explains. “You shouldn’t have to feel compelled to live up to an externally set, arbitrary standard. You should have the control.”

How corsets took over the world. By Zoë Kendall. i-D , May 25, 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment