The

key to unlocking the mysterious magic of Swiss-born artist Félix Vallotton,

whose paintings and woodcuts are the subject of a major exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art in London, can be found in a

scene from a novel no one remembers: La Vie Meurtrière (or The Murderous Life),

which Vallotton wrote in 1907, when he was 42. In it, Jacques Verdier, the

narrator of this fictionalised autobiography, recalls an incident from childhood

when he and his friend Vincent were walking atop a riverside wall. Vincent was

striding in front, struggling to keep his balance on the stone wall, when

suddenly the setting sun threw Verdier’s shadow forward, startling his friend.

Vincent slipped and fell into the water, causing serious damage to his head.

Was

Verdier responsible? Vincent thought so, and before long everyone else did too.

It was, after all, some dark aspect of Verdier that had, in a sense, whether

consciously or not, lunged forward and tripped his friend up, causing his

injuries. But are we really responsible for the misdemeanours of our

silhouettes? Is the shape of our lives determined as much by the consciousness

of shadows as it is by the intentional actions we deliberately take? As the

novel unfolds, Verdier’s ill-starred shadow hangs over one suspicious incident

after another – from the death of an engraver (who accidentally stabs himself

with a copper burin when spooked by Verdier’s presence) to that of an artist’s

model, who slips when reaching for Verdier’s hand and falls fatally into a

scorching stove.

The

worlds that Vallotton conjures, whether in word or image, are invariably

defined by a conspiracy of shadows. They whisper in secret. They frame us.

Take, for example, Vallotton’s intriguing gouache-on-cardboard interior, La

Visite (The Visit) (1899) – one of the stand-out works on display in the

exhibition. At first glance, the scene seems innocuous enough, tender even: a

man and woman, dressed to the nines, are locked in close, as if reliving the

romantic embrace of the final dance they’d enjoyed earlier that evening before

returning home.

Look a

little closer, however, and an awkward stiffness in the woman’s neck is echoed

by the backwards roll of her tightening shoulders. She’s tense, scared. Her

left hand, on further inspection, is not cradled consensually in a clasp with

his right hand, but rather is restrained by it. This is no dance. It's a

prelude to an assault. He’s bracing for a struggle that he knows is inevitable,

because he’s orchestrating it. That the two are on the verge of tumbling into

an abyss of violence is most powerfully portended by the commingled spill of

their entangled shadow. Having already begun to devour her legs, their blurred

shadow bleeds out aggressively to the right, engulfing a bookcase that one

imagines is filled with Gothic tales of stranglings and poisonings he no doubt

collects. A displaced cushion on the carpeted floor, about to be swallowed by

the plush maw of the velvet sofa, which itself seems woven more from shadow

than thread, is a further clue that things are about to get troubled. To the

left, a bedroom yawns open like a cage.

“I think

enigma is what it’s about,” Ann Dumas, who conceived and curated the exhibition

Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet, tells me when I ask her what underlies

the vexing narratives of Vallotton’s art. “It’s always a man and a woman

interacting in a more than slightly claustrophobic, bourgeoise interior,” she

explains. “You never quite know what the relationship is, what the transaction

is. You always get the sense it is some kind of illicit relationship.”

Vallotton

was born in the Swiss city of Lausanne in 1865 and moved to Paris when he was

16 to pursue his ambition of becoming an artist. He would live in France for

the rest of his life, becoming a citizen in 1900. Resuscitating a tradition

that had steadily declined in popularity and prominence since the Renaissance,

Vallotton first attracted attention in the early 1890s as a virtuoso maker of

woodcut prints. He shone a light on the lust, greed, hypocrisies of the middle

class in acerbic scenes characterised by their stark, black-and-white attitude

to social mores.

In one

such arresting vignette, Intimités V: L'Argent (Intimacies V: Money), created

in 1898, the year before Vallotton painted The Visit, we see the artist

experimenting with just how far shadow, as a palpable existential,

psychological and physical aspect of the human condition, can monopolise an

image. Here, a man desperately trying to explain himself to a woman whose

long-suffering soul has already checked out of the room and relationship in

which we find them, is about to be consumed entirely by an accumulating

shadowiness of Self that inundates the image from right – one that threatens to

submerge the two forever in its tsunami of asphyxiating darkness.

For a

time, Vallotton aligned his way of seeing with the short-lived mystical group

of symbolist artists known as ‘Les Nabis’ (Arabic for ‘The Prophets’), which

included Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard and disbanded in 1900. Though he

would retain the luscious brushwork he honed in the company of the Nabis,

Vallotton was never a heartfelt follower (the others called him ‘the foreign

Nabi’) and would go on to cultivate a strangeness of storytelling all his own –

one that balances a realism of figurative form with a mystery of amorphous

shadow.

“Vallotton

has never quite been given the exposure he deserves,” argues Dumas, who has

organised the first ever show in Britain to feature the artist’s paintings.

(The last show in the UK devoted to his work was over 40 years ago and it

focused almost entirely on his prints.) Why has Vallotton struggled to gain

traction outside his native Switzerland, unlike other former members of the

Nabis group? “I think he’s a tougher artist than they are,” Dumas tells me:

“he’s a strange and dark character. It may also have something to do with the

fact that he was Swiss. So many of his works ended up in Switzerland, partly

because his brother, Paul Vallotton, was an art dealer who established himself

in Lausanne. He sold a great deal of his brother’s work to Swiss museums and

private collectors, so Vallotton wasn’t in the mainstream of French art like

Bonnard and Vuillard.” In the century since his death, Vallotton has largely

fidgeted in the shadows of those two painters, as it were.

Career-spanning

in its scale, the exhibition takes visitors from the wrestlings of a young

artist struggling to find his visual voice amidst the feverish experimentations

of fin-de-siècle Paris, to one who, after achieving financial stability with

his marriage to a wealthy widow in 1898, was determined to make an indelible

mark on the unfolding story of art. “Visitors may be surprised,” Dumas tells

me, “by how much he changes over time.” She points, in particular, to how “he

becomes obsessed with the French neo-classical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique

Ingres and develops this cold hard-edged realism”.

To my

eye, even in such hard-edged works – ones that initially appear forensically scrubbed

of the menacing shadows that dominate his earlier woodcuts – a subliminal

darkness subsumes the narrative, dislocating its superficial realism, taking us

to a place that lies below the surface of seeing. In Red Peppers, for instance,

painted in 1915 when cultural consciousness was preoccupied with the horrors of

the World War One, a sharp glisten of waxy orange, red, and green capiscums,

offered to us on a crisp white plate, is barely intruded upon by the faintest

of subtle shadows falling palely to the right.

Here,

physical shade has been superseded by a darkness of psychic intrigue that

sculpts itself instead into the black handle of the knife that lies before us.

Its blade gleams with a murderous, haemoglobin glow that cannot be attributed

to any realistic reflection of the peppers themselves. Something sinister

vibrates outside the frame. The artist’s haunting shadow never fully fades.

In

Sandbanks on the Loire (1923), one of the last paintings Vallotton undertook,

created two years before his death – a work that Dumas describes as having “a

slight unstated sense of menace to it” – the mysterious tension between object

and shadow remains on full display. A fisherman has made his way to an eerily

still inlet whose glassy water mirrors the calm summer sky. At first glance, a

softness of dry, undulating banks and the billow of trees in fullest leaf seem

the very picture of peaceful contentment.

But, as

always, the shadows tell a different story. More angular than can be accounted

for by the pillowiness of the leafy branches from which they fall, the

clapboard shadows are oddly boxy in their secret carpentry; coffin-like.

Suddenly, the small boat on which the fisherman has conveyed himself to this

curious elsewhere seems more like a casket than a skiff. The murky message is

clear: there’s no coming back from where the shadows take you.

In 1897

or 1898, Edouard Vuillard gave Félix Vallotton one of his most important

paintings. Vuillard’s Large Interior with Six Figures appears in two of

Vallotton’s paintings, hanging on the wall and reflected in a mirror. It is

quintessential early Vuillard: an intimate world ruled by women, jigsawed into

place by wallpaper, curtains and rugs, any anxiety or conflict muffled by

patterns and layers of plush. Vallotton’s interiors, by contrast, trade on

male-female tension and gaping empty spaces. The smooth blocks of saturated

colour amplify the sexual frisson. Despite their different temperaments as

artists, Vallotton and Vuillard were both reserved men who navigated the

cultural efflorescence and political turmoil of fin de siècle Paris side by

side. Vuillard is much better known, but the first major survey of Vallotton’s

work in the UK is now on display at the Royal Academy (until 29 September),

almost a century after his death.

He was

born in 1865 in Lausanne to a chemist who later became a chocolate maker. At 16

he moved to Paris, where he studied at the Académie Julian and copied paintings

in the Louvre. He became captivated by Japanese prints after visiting the

Universal Exhibition of 1889 – a key source of inspiration. With no financial

backing, he took on various jobs during the 1890s: working as an art critic for

a Swiss newspaper, helping to restore paintings for a Parisian dealer,

illustrating a wide range of books, and churning out prints for the magazines

and political papers then proliferating in Paris (his most important

collaboration was with La Revue blanche). He also wrote three novels and eight

plays, two of which were staged.

In the

early 1890s Vallotton began to attract attention for his boldly synthetic,

black and white woodcuts and in 1893 he joined the Nabis, a group of young

avant-garde artists that included Bonnard and Vuillard. The Nabis liked

nicknames, and Vallotton’s was le nabi étranger (‘the foreign Nabi’). He

volunteered to fight for his adopted country in World War One, but was too old,

at 49, to enlist. Instead, he documented its horrors in a powerful series of

prints. Such political work was rare in his ‘mature’ period. La Revue blanche

had closed down in 1903, and after his marriage in 1899 to Gabrielle

Rodrigues-Henriques, the widowed daughter of the art dealer Alexandre Bernheim,

he was financially secure enough to be able to focus on painting.

Critics

and historians have lamented this shift because Vallotton was a terrifically

innovative printmaker, largely responsible for the revival of the woodcut

(Gauguin was close on his heels). Unlike many of his French colleagues, such as

Bonnard, Vuillard and Toulouse-Lautrec, who worked with professional printers,

Vallotton carved his own blocks and pulled his own prints. He was a natural,

combining the aesthetic elegance and abstraction of Japanese models with the

experimental freedom and playful spirit of the Nabis. His prints have something

of Daumier’s comedic intuition but Vallotton’s humour was several shades

darker.

The RA

exhibition presents Vallotton as a ‘painter of disquiet’, a description best

suited to the psychological tension of his interiors and the chilled eroticism

of his nudes. The dark comedy and social charge of his street scenes need a

different noun: ‘disquiet’ tamps down Vallotton’s humour and political anger.

It also sidelines his prints, which the exhibition itself does not. He had a

brilliant pictorial wit, not just sardonic and sharp, as is often remarked, but

full of sympathy. Look for the terror-struck, corpulent bourgeois failing to

keep up with a crowd that is being chased by the police (The Demonstration,

1893); the nude holding a tiny black dog inches away from her groin (Bathing on

a Summer Evening, 1892-93); the polar bear rug staring out at us from an

adulterer’s bedroom like a startled witness (The Other’s Health, 1898); the

toddler fiendishly ripping and scattering paper on the floor (The Red Room,

Etretat, 1899); or the schoolchildren portrayed as roving, belligerent gangs.

His work

has always presented a problem of tone, and this perhaps more than anything

else – his Swiss origins, his wholesale rejection of Impressionism – has made

him a mysterious and marginal figure. The writer and publisher Octave Uzanne

called his approach to modern street life ‘vaguely ironising’, hinting at how

difficult he is to pin down. But his ambivalence resonated: Octave Mirbeau

defended Vallotton’s pessimism against charges of aggression and arbitrary

negativity, describing it as a pessimism in sincere search of the truth.

The

problem of tone is also a problem of politics. Like Seurat, Vallotton

associated with anarchists such as Félix Fénéon, but never described himself or

his work explicitly as such. (One of his most famous woodcuts, The Anarchist,

captures this ambivalence.) He was a laconic man: his early letters home are

brief, not much more than worries about money and ‘please send more chocolate.’

We know very little about his inner life. But his street scenes are alive with

political tension and his interiors poke holes in the moral façade of the

bourgeoisie.

The

rarely seen triptych The Bon Marché Department Store (1898) is a triumph of the

exhibition. In a characteristically self-critical gesture, Vallotton implicates

himself: a placard in the central panel advertising ‘Jewellery and Objets

d’Art’ addresses the viewer, the consumer of his pictures, inviting us to see

ourselves as part of the crowd and his paintings as luxury products. Zola

described the department store as a modern ‘cathedral of commerce’, a temple of

leisure, with shopping the new sacred rite. (At the Royal Academy the triptych

hangs across from Bathing on a Summer Evening, a radical reimagining of the

fountain of youth as a public swimming pool, to underscore the point.)

Vallotton makes the crowd his protagonist, but the left-hand panel depicts an

exchange between a man and a woman, presumably salesman and client. Surrounded

by soaps and perfumes, their appraisal of lipsticks is unnervingly intimate –

hands touching, heads bowed in mock-pious contemplation. A woodcut of the Bon

Marché hung nearby shows a similar scene of flirting and shopping, but in stark

black and white: a mating ritual corrupted by the drive to make a sale. The

exhibition’s arrangement emphasises the interplay between printmaking and

painting that defined Vallotton’s early career and suggests connections between

the psychosexually charged interiors and the more political urban scenes.

Vallotton

liked to position his viewers as semi-detached onlookers, even voyeurs. Uzanne

wrote that he captured the ‘bulimic curiosity’ of people in the streets, always

on the lookout for spectacles to consume. In many of his interiors, both

paintings and prints, he invites us to invade a fraught private moment, almost

always between a man and a woman: a quarrel, a disappointment, an assignation.

In others, we simply sneak up on someone from behind. This is the set-up in

Woman Searching through a Cupboard (1901) and Interior with Woman in Red

(1903), both of which show Vallotton’s wife, Gabrielle.

In Woman

Searching through a Cupboard, what appears to be a mundane domestic moment is

made mysterious by the lamp on the floor, which illuminates the nocturnal

scene. Gabrielle has crouched down to examine (to read?) something: her head is

bent and we see only her black silhouette, in contrast to the glowing lampshade

beside her, painted with colourful boats (Vallotton decorated it for her as a

gift). Only the merest hint of the object she was searching for is visible: the

edges of two boxes stacked on the cupboard floor. We are led to wonder what

secrets they contain. This was the first painting Vallotton exhibited in

London, in 1913; it is now, like much of his work, in a Swiss private

collection. It’s worth the price of admission to see this alone.

In

Interior with Woman in Red, we are positioned (again) a few feet behind

Gabrielle, watching her gaze through a series of rooms littered with discarded

clothes. This view from behind is also at play in an earlier work, The Sick

Girl (1892): we see only the girl’s neck and shoulders as she sits up in bed,

but they give us a visceral sense of her discomfort and ennui. Vallotton’s

voyeurism is distinct from Degas’s, whose scenes of women bathing or lounging

in brothels are charged with physicality. With Degas we are voyeurs of women’s

bodies, or (to put it more generously) of women unselfconsciously using and

tending to their bodies. With Vallotton, we try to know their minds. The

tremendous challenge of such an aim – especially for visual art – is the reason

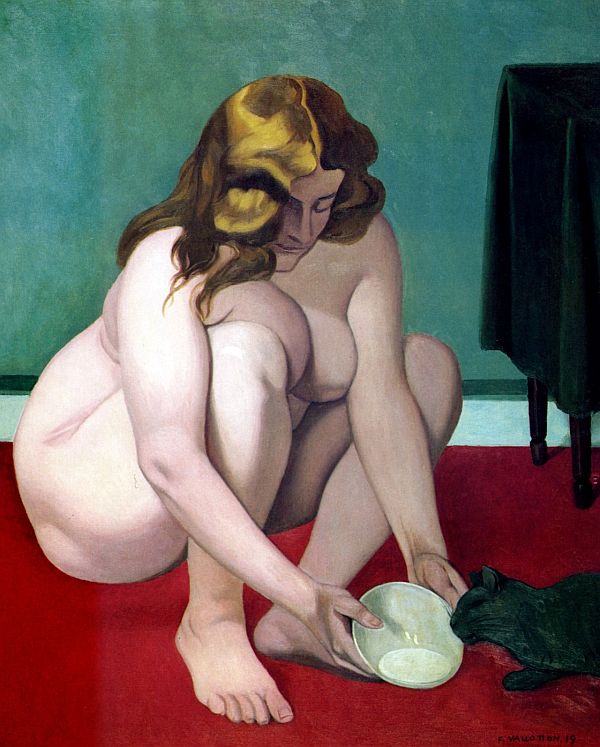

mood and motivation are often unclear. Perhaps it is also the reason that his

nudes are usually disappointing, especially at large scale. They abandon

psychological subtlety for too much malformed, cold-blooded flesh. Thankfully,

there are only a few nudes in this exhibition, and at least one of them is

worthwhile: a startling remake of Manet’s Olympia entitled The White and the

Black (1913), which turns the racial tensions of the original on their head.

In 1903,

the same year the Nabis disbanded and La Revue blanche ceased publication, the

Galerie Bernheim-Jeune put on a double exhibition, Vallotton and Vuillard.

Vallotton displayed 75 paintings to Vuillard’s ten, making the most of his

familial advantage in the first major show of his career. Such a lopsided

display couldn’t have been good for their friendship, but they remained close. Vallotton

kept a diary during and after the war; it makes clear how much Vuillard’s

‘equilibrium’, ‘tenderness’ and ‘nourishing chatter’ sustained him, tempering

his self-diagnosed bitterness and neurasthenia. These late reflections read

like torrents of emotion by Vallotton’s standards, but his reserve peels away

if you look long enough at the work.

At the

Royal Academy. By Bridget Alsdorf. London Review of Books, September 26, 2019.

The Cone

sisters of Baltimore, Dr Claribel and Miss Etta, inherited a fortune stitched

from cotton, denim and mattress ticking, and chose to spend it on art. They

bought, mainly in Paris, over the first decades of the 20th century, ending up

with one of the greatest assemblies of Matisse, plus works by Picasso, Cézanne,

Van Gogh, Seurat and Gauguin. Before Dr Claribel died in 1929, she signed one

of the most manipulative wills in the history of art. Her share of the

collection would go in the first instance to her sister, with the

"suggestion, but not a direction or obligation" that after Etta's

death it pass to the local museum of art "in the event the spirit of

appreciation for modern art in Baltimore becomes improved". This wonderful

challenge from a dying woman to an entire city was coupled with the proposal,

or threat, that the Metropolitan Museum in New York should be the fallback

recipient. The next 20 years - until Miss Etta's death in 1949 - naturally

contained some major politicking from the Metropolitan, but plucky little

Baltimore eventually proved its fitness and modernity. The Cone collection is

now the main reason for visiting the Baltimore Museum of Art on the campus of

Johns Hopkins University.

When I

was teaching there a dozen years ago, I used to call in at the museum between

classes. At first, Matisse and the other big names occupied me, but over the

weeks the picture I would find myself standing most faithfully in front of was

a small, intense oil by the Swiss artist Félix Vallotton. The Lie had been

painted in 1897 and bought 30 years later by Etta Cone from Félix's art-dealing

brother Paul in Lausanne. It cost her 800 Swiss francs - little more than small

change, given that on the same day, and from the same source, she bought a

Degas pastel for 20,000 francs.

One of

my writing students handed in a story based around a mysterious lie, and so I

found myself describing the Vallotton to my class. A man and a woman sit in a

late 19th-century interior: yellow and pink striped wallpaper in the

background, blocky furniture in shades of dark red in the foreground. The

couple are entwined on a sofa, her rich scarlet curves bedded between the black

legs of his trousers. She is whispering in his ear; he has his eyes closed.

Clearly, the woman is the liar, a fact confirmed by the smiling complacency of

the man's expression and the way his left foot is cocked with the jauntiness of

the unaware. All we might wonder is which lie he is being told. The old

deceiver, "I love you"? Or does the swell of the woman's dress invite

that other favourite, "Of course the child is yours"?

At my

next class, several students reported back. One, the Canadian novelist Kate

Sterns, politely told me that my reading was diametrically wrong. For her, it

was obvious that the man was the liar, a fact confirmed by the smiling

complacency of his expression and the jauntiness of his cocked foot. His whole

posture was one of smug mendacity; the woman's that of the pliantly deceived.

All we might wonder is which lie she is being told. If not "I love

you", then perhaps that other male perennial, "Of course I'll marry

you". Other students had other ideas; one cannily suggested that the

title, rather than referring to a specific untruth, might be a broader allusion

- to that necessary lie of social convention that makes honest dealing between

the sexes impossible. Vallotton's use of colour might confirm this. On the left

are the couple in sharply contrasted hues; on the right, a scarlet armchair

blends seamlessly with a scarlet tablecloth. Furnishings can harmonise, we

might conclude; humans not.

Vallotton

(1865-1925), like compatriots as various as Liotard, Le Corbusier and Godard,

did that Swiss thing of appearing to the outside world to be French; indeed, he

went further, and a year after marrying into the Parisian art-dealing family of

Bernheim in 1899, took French citizenship. He was a member of the Nabi group

and a lifelong friend of Vuillard. Not that any of this raised his profile in

Britain. The Lie was the first Vallotton I looked at long enough to register

the name; and domestic gallery-goers needn't be embarrassed if they find it

unfamiliar. Any embarrassment better belongs to the nation's art acquirers. A

recent check with the Fondation Félix Vallotton revealed that we have only a

single painting of his in public ownership, Road at St Paul (1922). It belongs

to the Tate, but it hasn't been displayed or loaned out since 1993.

It isn't

easy tracking him down. Many of his paintings remain in private hands, and

unless you go to Switzerland, you are unlikely to come across more than a

couple hanging together. But there is another reason why he has sometimes been

bypassed and undervalued. He is a painter who, more than any other I can think

of, ranges from high quality to true awfulness. The Musée des Beaux-Arts in

Rouen, for example, has two Vallottons on display in a rather dingy and crowded

corridor. One is a theatre study, of nine tiny blackish heads peering over the

rail, made speck-like by the vast creamy-yellow bulge of the balcony front

beneath them. It has none of the busy impressionism, the shifting light and the

gilt of, say, Degas or Sickert's theatre work; it is bluntly affectless,

modern, Hopperish. But on the opposite wall of the corridor is a nude of such

turn-your-back dreadfulness that had you seen it first, you might have noted

the artist's name in order to ensure you avoided his work at all costs in the

future.

So the

opening of the biggest Vallotton show in years at the Zurich Kunsthaus set off

an anxious anticipation: what if he was one of those artists of whom the more

you see, the lower your overall opinion becomes? And how would the curators

play it? Would they dutifully show a cross-section of all his work, or merely

go for the best stuff?

The

answer, curiously, is that they have done both. They have assembled a show of

great variety and brilliance; but they have also confronted head-on the problem

of Vallotton's nudes and tried to make a new case for them. Out of 90

paintings, there are 20 or so of his most dubious and reviled works. Both

catalogue jacket and poster girl are boldly taken from this section.

My first

response to this concentrated show - which deliberately excludes preliminary

drawings, woodcuts and sculpture, let alone diverting display cases of letters

and holiday snaps - was one of relief: that Vallotton was an even better artist

than I had imagined, and over a wider range of subject matter. My second was a

realisation that, for all his nationality-taking, his absorption into the Revue

Blanche circle, his summers at Etretat and his status as "the foreign

Nabi", he was hardly a French artist at all. In 1888, after a trip to the

Netherlands, he wrote to his friend the French painter Charles Maurin: "My

hatred of Italian painting has increased, also of our French painting ... long

live the north and merde to Italy." The French Nabis were painters of the

great indoors, and even when they went outdoors they were painting interiors:

their bushes and trees might be soft furnishings, their flowers part of a

wallpaper repeat; you never feel the breeze, or much weather apart from the

sun. Vallotton was always being pulled north, towards Germany and Scandinavia,

to hard edges, to narrative, to allegory. Perhaps his last act of solidarity

with his French colleagues was when he, Bonnard and Vuillard were offered the

Légion d'Honneur at the same time. All of them turned it down.

In

Zurich, The Lie blazes out from the middle of five related paintings known as

Intimités. They date from 1898, and so from the period when he was closest to

the Nabis. They share the cut-out composition and sumptuously opposed colours

of early Vuillard; also the interior setting and (in several cases) tenebrous

lighting. But the French Nabis are - despite recent attempts to biographise and

narrativise their work - fundamentally pure, and the figures who inhabit their

spaces are aestheticised along with the furnishings. Vallotton's figures have a

life beyond the paint that depicts them; they both offer and withhold a

narrative. A brown-suited man waiting for a woman to arrive squints out of a

window while seeming to camouflage himself in the heavy brown curtains: is he

shyly hopeful or menacingly predatory? In The Visit, another man (or perhaps

the same one) greets a purple-coated woman, and the force-lines of the painting

lead you ineluctably to the open bedroom door at the back left: but who is in

charge here, who is controlling, who is paying? Critical tradition has dubbed

this series "violent interiors", but that seems to be reading too

much sexual politics into them; rather, they are paintings of deep emotional

dissonance.

They

also remind us that Vallotton was a rare artist in another respect: he had

literary ambitions. Many painters keep journals - he did, too. But he also

wrote eight plays, two of which were briefly produced, and three novels, none

of which found a publisher in his lifetime. The best of these, La Vie

Meurtrière, is a truer "violent interior": the Poe-ish story of a

lawyer turned art critic who from childhood finds that his mere presence brings

death to those around him. He is there when a childhood friend falls into a

river, when an engraver stabs himself with his burin and dies of copper

poisoning, when an artist's model falls against a stove and suffers fatal

burns. How complicit, or unwitting, is he in what happens? Is he obscurely

cursed, and if so, how can he avoid causing further deaths? Vallotton's

narrative is another organised enigma.

The

Zurich show reveals that Vallotton was a fine portraitist: there is a massively

brooding image of Gertrude Stein (also from the Cone collection). The sitter

disliked it - always a badge of honour - and took revenge by dismissing

Vallotton in her autobiography as "a Manet for the impecunious".

Given that she seems to have got the painting for free, this seems as

impertinent as it is snobbish.

He was

also an accomplished painter of still lives - formidably good at red peppers -

and an extraordinary landscapist. The landscapes, constantly surprising, are

the great wonder of this show. They contain occasional remnants of Nabism in

the use of cut-out forms and extreme colour contrast, but the sensibility is

quite different: Sunset at Villerville (1917), almost hallucinatory in its

swathes of orange, purple and black, is closer to Munch.

These

paintings - mostly from the last 15 years of Vallotton's life - also vary

technically within themselves: The Pond (1909) contains some areas rendered

impressionistically and others painted with hard-edged realism, while a stretch

of murky black water seems to mutate into a vast and sinister flatfish as you

look at it. There is often something dissonant about them; in their way, they

are as enigmatic as the Intimités. Perhaps this is because they were often

paysages composés - put-together landscapes. Vallotton would go out into

nature, make sketches and notes, then return to his studio and assemble the

picture using material from different sites: a new, technically non-existing

nature, created for the first time on canvas.

And

then, inevitably, there are the nudes. A Swiss friend of mine, looking forward

to the current exhibition, asked ruefully: "Have you ever seen a good nude

by Vallotton?" Yes, two now, both of them early. Étude de Fesses (c1884)

is a bum-shot of extraordinary realism, as careful a rendition of human flesh

as anything by Courbet or Correggio. Bathing on a Summer Evening (1892-93), in

which women of various ages and body shapes undress and take the water, has an

ethereally cross-cultural feel to it: part Japanese-y stylisation, part

Scandinavian myth, part revisiting of the old Fountain of Youth theme. When

first shown at the Salon des Indépendants, it caused a scandal, and Douanier

Rousseau, standing in front of it, said fraternally to its author: "Well,

now, Vallotton, let's walk together."

But

Vallotton was always walking along his own path, and it led to an increasing

concentration on monumental images of the female nude. He came to it through a

study of Ingres, proving that great painters, like great writers (Milton,

famously), can be pernicious influences. Vallotton revisited several of Ingres'

well-known subjects (Le Bain Turc, La Source and Roger and Angelica - the last

on show in Zurich) in a way so pointlessly inferior that you wonder he ever

showed them or sold them. This is the more frustrating because elsewhere

Vallotton showed he could update and appropriate brilliantly. La Chaste Suzanne

(1922 - not on show) is his version of Susannah and the Elders: the biblical

bath becomes an enclosing pink banquette in a plush bar or nightclub, and the

elders two sleekly bald businessmen. It is intense and menacing, yet also

enigmatic: the planned victim looking - to this eye, anyway - distinctly

calculating and up to speed. In modern times, the painting suggests, it might

well be Susannah who turns the tables and blackmails the elders.

The 20

or more nudes on display in Zurich confirm what might be called Vallotton's

law: that the fewer clothes a woman has on in his paintings, the worse the

result. There are charming early studies of his wife, Gabrielle, in a long

nightdress, and another of a model beginning to take off her chemise; next come

a couple of iffy peek-a-boo studies of women with shoulder-straps lowered; then

comes the Full Félix.

The

problem isn't the catch-all feminist objection, that these nudes - as an

American critic put it - show "the gaze of the male voyeur whose

penetrating stare violates and humiliates the object of its focus". Nor is

it that the subject of the unattended nude in a modern room reminds us how much

better it was to be done by Hopper (who could have seen some of the Swiss

painter's work during his Parisian stay of 1906-7). It is, first, that most of

these nudes are dismayingly inert; they might as well have been sculpted from

putty for all the life and breath they have in them. And second, they often do

not even convince within themselves: they might, indeed, be nus composés,

assembled from different women. Reclining Nude on a Red Carpet (1909), for

instance, looks as if the painter put his wife's head on an Ingres neck and

then attached both to a model's body.

The

monumental nudes illustrating allegorical subjects are even worse, so bad that

the critical defence now being raised is that they must, of course, be knowing,

self-aware, ironical. This strikes me as the pleading of desperation; and also

runs head-on into the problem that it is rare for an artist of mature years to

emerge into an irony about the very process of art after a career that had

never previously displayed it. Perhaps Vallotton was too consciously aiming for

immortality, forgetting that it is rarely endowed in accordance with an

artist's wishes.

At some

speed, I left the nudes behind and returned to The Lie, which held a final

surprise for me, one now emphasised by the hulking nudes. It is tiny - indeed,

the smallest painting in the entire show. If I had been asked, before going to

Zurich, how large it was, I would probably have guessed about four times its

actual area. It is strange how time and absence can do this to paintings that

you admire and think you know well: a version of going back to a place you

visited as a child and realising how different its proportions actually were.

With paintings, you tend to remember the small ones as bigger than they are,

and the big ones as smaller. I do not know why this should be the case, but am

happy to leave it - appropriately enough, in Vallotton's case - as an enigma.

· Félix

Vallotton: An Idyll at the Edge is at the Kunsthaus, Zurich, until January 18,

and at the Kunsthalle, Hamburg, from February 15 to May 18 2008

Better

with clothes on. By Julian Barnes. The Guardian, November 3, 2007.

No comments:

Post a Comment