Painting

and love are like sisters; they are very different, of course, but are tightly

connected and related in many ways.

–

Isabelle Graw

The

familiarity of post-medium discourses today has, curiously, set the scene for

painting’s resurgence as an art form. Despite its gendered and discriminatory

history, painting remains valorized in contemporary art, and it is used towards

powerful feminist ends. Certain understandings of painting today might even be

incognizable within traditional definitions, as the medium looks or works more

like sculpture, performance, or pure network formation. At the moment of

capitalism’s digitization, its material obsessions are far from diminished.

Isabelle

Graw maps the forceful paradoxes driving painting’s continuous critical and

commercial allure in her landmark new publication, The Love of Painting.

Genealogy of a Success Medium (Sternberg Press, 2018). Graw keeps a close eye

on painting’s fourteenth century theoretical foundations, developing a distinct

genealogy of the medium’s dazzling vitality in the present. Interwoven among

the volume’s essays are dialogues with numerous artists whose work Graw

examines, as she considers the critic’s networked position and complicates her

interpretative strategies. In a public discussion marking the book's US launch,

she outlines some of her major arguments, inviting responses from David

Joselit, Distinguished Professor of Art History at The Graduate Center, CUNY,

and New York-based painter Avery Singer.

Book

Launch & Discussion Documentation. Artists Space, New York City , May 21, 2018

Painting

seems to have lost its dominant position in the field of the arts. However,

looking more closely at exhibited photographs, assemblages, installations, or

performances, it is evident how the rhetorics of painting still remain

omnipresent. Following the tradition of classical theories of painting based on

exchanges with artists, Isabelle Graw’s The Love of Painting considers the art

form not as something fixed, but as a visual and discursive material formation

with the potential to fascinate owing to its ability to produce the fantasy of

liveliness. Thus, painting is not restricted to the limits of its own frame,

but possesses a specific potential that is located in its material and physical

signs. Its value is grounded in its capacity to both reveal and mystify its

conditions of production. Alongside in-depth analyses of the work of artists

like Édouard Manet, Jutta Koether, Martin Kippenberger, Jana Euler, and Marcel

Broodthaers, the book includes conversations with artists in which Graw’s

insights are further discussed and put to the test.

“Isabelle

Graw’s brilliant analysis of the exceptional position of painting in our

increasingly digital economy combines a deep respect for the objects of study

and those who make them with an impressive range of critical and theoretical

insights. Along the way, The Love of Painting never loses sight of the medium’s

dialectical relationship to the art world, the art market, and society at

large. This is a lively, provocative, and persuasively argued book.”

—Alexander

Alberro, author of Abstraction in Reverse: The Reconfigured Spectator in

Mid-Twentieth-Century Latin American Art

“It’s

about time for a book declaring 'the love of painting' to appear, after the

aridity of postmodernism’s announcement of painting’s demise. Isabelle Graw’s

argument in favor of this love turns on what she terms 'vitalistic fantasies':

the perception of artworks as 'quasi subjects' saturated with the life of their

creator. This notion of the work of art as a quasi subject relates directly to

the philosopher Stanley Cavell’s consideration that 'the possibility of

fraudulence, and the experience of fraudulence, is endemic in the experience of

contemporary art.' To understand this we must ask: Why do we relate to works of

art in the same way we relate to people? The Love of Painting works on this

question—and does so with success.”

—Rosalind

E. Krauss, author and University Professor at the Department of Art History,

Columbia University

Avery Singer. The Studio Visit, 2012

Rachel

Harrison’s Rubber Maid (2018) is composed of a mixed-bag of materials—acrylic,

wood, enamel, cement, polystyrene, and a Rubbermaid mop bucket, complete with

wringer—the bright gold textured plank, embellished by pink and blue spray

paint, touches a similarly-hued plastic bucket on the floor beside it. Included

in the exhibition Painting: Now and Forever, Part III (June 28 – August 17,

2018) across Greene Naftali and Matthew Marks galleries, Harrison’s

three-dimensional piece is indicative of what Isabelle Graw terms an “elastic

conception of painting.” What has a painting historically been, and what is it

now? In her new book The Love of Painting: Genealogy of a Success Medium, art

historian, critic, and educator Graw ruminates on Harrison’s paintings, and the

work of Martin Kippenberger, Avery Singer, and Marcel Broodthaers, among

others, tracing the origins of the medium, its evolution, and its enduring

significance.

Graw

outlines her arguments in the book’s introduction, “rather than indulging in

the love of painting…I attempt to trace the material, art-historical, and

sociological reasons for this art form’s specific potential in view of a

contemporary capitalist system that has increasingly turned into a digital

economy,” and assembles a thematic scaffolding that runs through the critical

essays, case studies, and conversations with artists contained within. She

asserts that painting has “intellectual capacities,” citing writings by Leon

Battista Alberti and David Joselit that discuss the medium’s ability for

agency, in addition to utilizing formation (as Michel Foucault ascribed it) to

characterize painting’s dialectical general-yet-specific nature. She connects

this to materiality’s relationship to affect and the semiotic and commodity

aspects of painting. Graw also puts forth her view of “vitalistic fantasies” (how

the personality of a painter may be evident in her painting, or how paintings

achieve personas) as they relate to a viewer’s engagement with the medium.

These examples are offered as possible reasons why painting has continued

relevance and renewal within the sphere of contemporary art.

Graw

explains that “in recent years, painting has received much more attention in

critical writing and theory, and contemporary painting exhibitions have been

extremely popular, bolstering an increased interest in the art form.” This is a

counterpoint to the idea that painting has lost relevance since the middle of

the last century due to the proliferation of performance, video, and

installation art. Painting has not only persisted, but morphed and acclimated,

as Graw delineates through her evaluations of artists’ practices. From the

outset, she states that her writing will focus on the discourse surrounding

painting primarily in Western Europe and North America, and that “the ideas and

values associated with painting in this book are thus characterized by Western

thought, and are not easily applicable to non-Western painting.” It is useful

to be told of the scope, though a mention toward a larger reach may have been beneficial.

A

collection of Graw’s meditations on this art form, The Love of Painting is

organized into six chapters, where each section combines case studies, essays,

and conversations thematically in a mixture of previously published and new

work. At times the prose is discursive, but this is ultimately helpful to draw

out her most salient points regarding vitalism, subjectivity, semiotics, and

value.

A

co-founder of both the Berlin-based art periodical Texte zur Kunst and the

Institute of Art Criticism based in Frankfurt (am Main), Graw draws from a rich

cache of critical writing to situate her thinking—the notes at the end of each

chapter are plentiful and worth perusing by those interested in her source

archive. She engages with the practices of over a dozen artists, including

Frank Stella, Édouard Manet, Joan Mitchell, Ellsworth Kelly, Gerhard Richter,

Jutta Koether, and many more in her comparisons and appraisals. Conversations

with friends Koether, Charline von Heyl, Merlin Carpenter, Wade Guyton, Alex

Israel, and herself on the merits of Jana Euler’s work are the most enjoyable

to read and are successful at elucidating Graw’s hypotheses on the prominence

of painting today. In her conversation with Koether, Graw ponders Joan

Mitchell’s style as an “alternation between impulsive action and a considered

approach” with a nod to the “conceptual expression” of Kippenberger’s

paintings. Koether does not wholly agree, answering “after all, conceptual

expression, even if it’s present here, is based on completely different premises.”

The close relationships between the writer and her artists are important, as

they lend an intimacy to the conversations which allows for honesty and

disagreement.

In her

essay on Harrison and Isa Genzken, Graw names the figure-like assemblages found

in both artists’ practices “quasi-subjects”, which she defines as “objects that

behave (or seem to behave) as subjects, as though they are possessed of agency

and changeable inner states and capable of acting upon their environment.” The

works reflect lives burdened by the struggle to survive in late capitalism, a

struggle that, for most artists working today, is all too real. The book

culminates on the subject of value and the work of painters in a neoliberal

economic context. In an increasingly digital (art) world, painting occupies a

particular space that reinforces its appeal and worth.

Isabelle

Graw's The Love of Painting: Genealogy of a Success Medium. By Lauren Palmer.

The Brooklyn Rail , September 4, 2018.

Rachel Harrison, Alexander the Great, 2007

Art

historian and critic Isabelle Graw’s loquacious book The Love of Painting: Genealogy

of a Success Medium — a rumination on the long history of painting and its

significance in the contemporary art world — is easy to esteem but tough to

love. Passionate ardor requires none of the elaborate rationalizations that

take place between these covers. If you need to be convinced to love something

the author calls a “meta-medium” through an avalanche of appeals to

art-historical tradition and critical opinion, then that ain’t amour.

That

said, by mingling the surface heft and vibrant shimmer that is contemporary

painting, this corpulent German-American-French-centric paperback effectively

blurs the lines between the artist-subject and the sensual painted-object.

The book

is thematically organized into six chapters that offer lively evaluations of

various painters’ practices; Graw’s thoughts on Frank Stella’s early black

paintings and Joan Mitchell’s general struggles are topnotch. Other essays

offer valuable insight into the work of Édouard Manet, Gerhard Richter, Sigmar

Polke, Rachel Harrison, Martin Kippenberger, Avery Singer, Marcel Broodthaers,

Jana Euler, Ellsworth Kelly, and Isa Genzken.

These

polished reflections are interspersed with significantly shallower

conversations between Graw and her contemporary artist “friends,” including

Wade Guyton, Jutta Koether, Charline von Heyl, Merlin Carpenter, and Alex

Israel. Through these conversations, Graw tries to refute claims of

contemporary paintings’ mannerist zombie stature. A co-founder of both Texte

zur Kunst and the Institute of Art Criticism based in Frankfurt, Graw seems to

view these friends of hers as the reason why painting now has meta-level

relevance within the sphere of contemporary art — because their work exhibits

“unspecific-specific” attributes of “quasi-people” (don’t ask) while being a

“comeback” commodity exchange chip always popular with the auction houses.

There is

no index (which annoys), but each chapter is generously illustrated in color,

which helped me follow along with gabby Graw as she traced the material,

art-historical, and sociological reasons for the “specific status” of painting

within the capitalist system. She posits that the artist’s individual human

touch is part of what elevates painting to this “special status,” but she fails

to adequately demonstrate this: intimate touch and bodily presence usually

plays an even more significant role in most performance art, drawing, and

ceramics. But it’s cool that Graw divines haptic touches even in mechanical

artistic processes — for example, in the scratches and dust on Guyton’s inkjet

print paintings.

If Graw

was entirely sincere about her love of painting (which she is not: her true

feeling, she eventually confesses, is “love-hate”), she might have skipped the

formalist questions and spent more time investigating sex, love and gender in

the history of the genre, where political content merges with form and

materiality in complimentary communion. Rather, what we hold in our hands is an

aggressively nerdy book inspired by paintings’ brush with death.

Since

the 1960s, prissy painting has wrestled with its mortality. Suddenly, though,

it feels more alive than ever. Following Douglas Crimp’s essay The End of

Painting and Ad Reinhardt’s Black Paintings series (1953-67), supposedly the

last paintings that anyone can paint, Graw makes frenemies with this demise by

placing it within the post-medium condition of Rosalind Krauss and the

expanded, “transitive” understandings of painting proposed by David Joselit.

For some reason, she failed to mention Nicolas Bourriaud, Peter Weibel and

Félix Guattari’s use of the “post-medium” term. Those additions, and a

consideration of the post-media condition, could have considerably enriched her

institutional critique.

Thought-provoking

assessments of painting’s death (or near-death) aside, Graw maintains that “in

recent years, painting, after losing its dominant position, has received much

more attention in critical writing and theory, and contemporary painting

exhibitions have been extremely popular, bolstering an increased interest in

the art form.” Fair enough, but she might have raised the question of whether

such popularity places painting on a dangerous path to derivative conformity.

After

citing Marcel Duchamp’s reframing of his paintings as symbol-discourse, Graw

offers a fascinating breakdown of her concept of painterly “vitalistic

fantasies,” suggesting that a painter’s personality manifests in their work,

which is what lends a painting a particular panache, and allows viewers’

perceptions to transform these flat objects into “quasi subjects” saturated

with their creators’ lives. This enchanting proposition is very interesting to

me as an artist who amalgamates artificial life with painting, particularly

when Graw insists upon paintings’ “production of aliveness.” This jubilant,

vitalistic view of painting might also relate to viewers’ engagements with the

phantasmagorical aspects of painting — thus serving as another key counterpoint

to claims that painting is irrelevant within our electronic wonder world.

How

Painting Survives in the Digital Era. By Joseph Nechvatal. Hyperallergic , March

18, 2019.

A

well-attended lecture by Isabelle Graw, a professor of art theory and a

founding editor of the journal Texte zur Kunst, was titled “The Economy of

Painting: Notes on the Vitality of a Success-Medium and the Value of

Liveliness.” Jetlagged from a flight from Germany, Graw framed her talk as an

eight-step analysis of the naturalization of painting in the contemporary

moment. In the late 1990s, she said, painters “felt pressured to justify

themselves,” but this anxiety fell away by the early 2000s, because of social,

economic, and historical reasons. Probably most important is that artists since

then have absorbed the critique of painting and consequently renewed the

primacy of the medium.

Graw’s

term for the renewal of painting is “vitalist projection.” Her point of departure

was Hubert Damisch’s ideas about the indexical signs traditionally associated

with painting, such as the brushstroke, which imply subjectivity. Brushstrokes

suggest “the traces of an activity to the eyes,” Graw explained, and act as a

finger pointing to the absent or ghostlike author. That a painting isn’t

actually alive but, because it exists in a material form, offers an illusion

that it can think and speak—this is vitalist projection. The labor and lifetime

of the artist are seemingly stored in the painting, she told us, but they are

not reduced to it. And what a painting actually depicts, Graw argued, is

irrelevant to this concept.

One

would expect Graw to provide examples from Western painting, from the

Renaissance to modern times, to give us an idea of the kind of work that

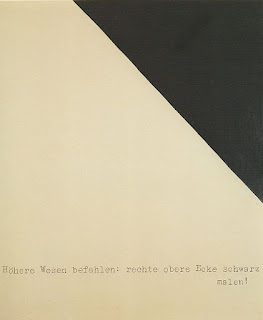

projects vitality. Instead she jumped to the late 1960s, when the German artist

Sigmar Polke ironically staged subjectivity as a display of affect. Paintings

such as Polke as Astronaut (1968) and The Higher Powers Command: Paint the

Upper Right Hand Corner Black! (1969), Graw said, invoke the presence of the

author but mock it. And based on its title, the latter work even suggests it

painted itself.

Graw

stated that she spent a year scratching her head over the question “What is

painting?”[1] For her, painting is not just a picture on canvas but also an art

that transgresses boundaries. Painting is revitalized, she said, when it pushes

boundaries, like when the French artist Francis Picabia tacked a stuffed monkey

to cardboard and painted words around it to create Natures Mortes (1920).

Incorporating spheres of labor, consumer goods, and written text into the work,

Graw said, breathed new life into painting. Similarly, Polke’s The Large Cloth

of Abuse (1968), a painting inscribed with German curses and insults, combined

fashion, art, and design—the artist wore the canvas as a gown before hanging it

on the wall. The Large Cloth thus becomes a discursive object that appears to

be alive—it can speak to us. But apart from the abusive language, what does it

say? Probably not much. As Raphael Rubenstein wrote in his review of the

artist’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, “It would be hard to find

an artist in recent times who was less forthcoming than Sigmar Polke

(1941–2010). He almost never gave interviews, and on the rare occasions when he

did so, his responses either mocked or otherwise frustrated the interviewer’s

quest for information.”[2]

Graw

cited other historical artists who revitalized painting (El Lissitzky, Yves

Klein, Niele Toroni) and added a few newer ones (Jeff Wall, Wolfgang Tillmans,

Rachel Harrison) whose work addresses ideas about painting but usually does not

incorporate any kind of paint. “It seems tempting to have a highly elastic

definition of painting,” Graw said, “to detect it everywhere,” but she didn’t

commit to going that far. Nevertheless, the medium can “push beyond the edge of

the frame,” she said, “while still holding onto the specificity of the picture

on canvas or to variations of this format.” I nodded my head to all of

this—elastic definitions of art are good—but still had one major question: When

exactly did painting exhaust itself? Why did the medium need to be renewed in

the first place? How did painting become moribund? Graw failed to establish the

norms against which her exceptions rebel. If academic approaches or religious

iconography were to blame, I wanted to know how vitalist projection worked in

them, or not.

Graw

discussed the narrow bond between person and product, in which the artist and

his or her creation overlap. In performance art, she said, this congruity is

achieved through the persona, a staged version of the artist. In the work of

Andrea Fraser, who was Graw’s example, the character invoked by the artist can

be separated from the artist herself. The identity of a painting and its

creator diverge: the painting “cannot be reduced to its maker because it’s

material,” Graw said, making the relationship metonymic. If I can discern a

difference between painting and performance, according to Graw, it’s that a

performed character is immaterial, brought to life by a person, whereas a

painting is a physical object that has a separate physical presence. But since

painting appears to be lifelike but really isn’t, what is she even going after?

I began to suspect that Graw was proposing a theory of painting based on the

lack of an idea. What a strange thing to do.

Graw

reviewed painting’s specific indexicality to the ghostlike author (which

doesn’t exist, right?), starting with Charles Pierce’s notion that a sign must

have a physical connection to an object, corresponding point by point. Pierce

cited photography, which has a factual connection to the world and, in Graw’s

words, “gives an automatic inscription of the object without presupposing an

author.” Do people still take this nostalgic if not ancient view of

photography—this it is mechanical, neutral, objective, and

descriptive—seriously?

Graw

decreed that an artist doesn’t have to touch a painting for it to have

subjectlike power—a power that she

repeatedly nullified as being an illusion. Like the work of Andy Warhol

and Wade Guyton, a painting could be made mechanically or by an assistant.

Through this, she said, imperfections can become improvements, which I took to

mean a revitalization. At this moment Graw acknowledged the primacy of painting

over other forms of art, such as sculpture, to express subjectivity, but her

argumentation was neither clear nor convincing. She pointed to Georg Wilhelm

Friedrich Hegel’s preference of painting over sculpture in his writing on

aesthetics, to the power given to painting historically, and to painting’s

familiarity to us. Her defense (because other people said so) was on shaky

ground.

The

American artist Frank Stella once said that painting is handwriting, Graw went

on, and some have understood Stella’s work as undermining the signature

style—despite him creating his own. The more artists erase themselves from

their work, Graw said, the more their subjectivity appears in it. “So there’s

no way to get rid of it, right?” she joked. Here Graw recognized that an artist

uses a mechanical process—like when the German artist Gerhard Richter drags

paint across a canvas with a squeegee—doesn’t signify detachment. Why can’t she

apply the same logic to photographers?

A

painting’s value is not its price, Graw said, but rather is “a symbolic and

economic worth that is attested to it once it circulates as a commodity.” (She

explored this idea in her enlightening 2010 book High Price: Art between the

Market and Celebrity Culture.) Valuable art, she continued, must be attributed

to an author—this in spite of millions of art objects in museums worldwide

(including paintings) whose makers have not yet been identified, or never will

be. As in steps one and two of her talk, Graw cited only a contemporary

example: Martin Kippenberger’s series of Hand-Painted Pictures (1992), which

satirized the desire to see the artist’s personal touch in painting.

(Kippenberger often had assistants or hired guns make his work—sometimes too

well, to the artist’s displeasure.) Graw explained that this desire becomes a

fantasy in collecting: when buying an artwork, a collector also buys into a

fantasy that he or she has now become part of the artist’s life. This idea was

the most compelling in her talk, and I would like to see Graw develop it.

The

Q&A session was scattered, with conversation between Graw and several

audience members revolving, in an uninteresting way, around the production of

digital images, and around Karl Marx’s definition of value and labor. Graw

summarized her argument again: liveliness is apparent in painting from the

Renaissance to the nineteenth century—though she never established when, how,

and by whom—and twentieth-century avant-gardes redefined that vitality as they

integrated art and life, something we usually understand as emancipatory. Yet

the new spirit of twenty-first-century capitalism, she began to conclude, has a

similar strategy: control subjectivity by transforming life into a currency, if

not a product to be bought and sold. Taking an autonomous, conversative view of

the function of art, Graw said that painting today fulfills the connection

between art and life. In fact, she said, it’s one of the last places for people

to find fulfillment. I am reminded of that quote attributed to Henri Matisse:

painting should be “a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a

good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.”

[1] Her

exact queries were: What do I mean when I say painting” and “What is my notion

of painting?”

[2]

Raphael Rubinstein, “Polke’s Plenitude,” Art in America (June/July 2014), 110.

Much

Detachment, Very Labor, So Painting. By Christopher Howard. In Terms of , June 27, 2015.

The

Economy of Painting: Notes on the Vitality of a Success-Medium and the Value of

Liveliness

Reporting a lecture

on June 4, 2015. Jewish Museum, Scheuer Auditorium, New York

No comments:

Post a Comment