“Creative” and its

variants are a versatile part of the vocabulary of contemporary capitalism,

able to link imagination, aesthetic practice, and religious faith in the

pursuit of private gain. The oldest word on creativity’s family tree is

“creation,” whose first meaning was specifically Christian—the term for the

divine genesis of the universe. One of the newest is the nominal form of

creative, normally an adjective for an original thinker or idea. Creative is

now also a count noun (think of the creatives who may be moving into your

shrinking rust-belt city) and a mass noun (get creative on the horn, said

account services to production). Many people would probably agree that

creativity is an essential human trait, crucial to a happy life, though this

noun is a relatively new coinage. An even more recent development is the notion

that creativity is a trait of capitalist markets. And in the United States, the

political phrase “job creators” borrows some of creation’s residual divine

light to illuminate the benevolent fiat of the capitalist, who is thought to

create jobs out of the formless void.

If creation has been

divine, creativity is decidedly human. The most important conflict in the

etymological history of “creative” is the struggle between its religious and

secular meanings. Before the late 19th century, to the degree that people could

participate in something called “creation,” it was only to approximate the

purity of the original, capital-C Creation, rather than inaugurating their own.

“There is nothing new under the sun,” Ecclesiastes reminded humans inclined to

creative hubris. “The created cannot create,” (creatura no potest creare) added

St. Augustine, insisting that such power resided only in God, and not in his

creations. In the history of the word “creative,” there are actually two

decisive rifts: this initial one between the divine and the human creation

suggested here, and then, once creativity became a human trait, a division

between its aesthetic and productive forms. We can roughly date this latter

conflict to around 1875, the earliest example of the word “creativity” given in

the OED, from an essay on Shakespeare’s singular brilliance.

Creativity was a work

of imagination, rather than production, of artistry rather than labor. One of

the consequences of this split between art and work has been to valorize

creativity as the domain of an intuitive, singular, historically male genius.

Productive creativity, meanwhile, is not art but labor, and thus rarely earns

the title of creativity at all; this is the supposedly unimaginative labor of

the manual worker or the farmer and the often feminized work of social

reproduction. There are obvious class and gender prejudices at work here;

coaxing a crop out of stubborn soil or preparing a family meal with limited

ingredients are not typically seen as creative acts, whereas cooking a

restaurant meal with the harvested crops often is. Other differences are rather

arbitrary. Children’s play is not thought to be brilliant in the way

Shakespeare is; it may, however, qualify as creative because it is appears (to

adults, anyway) to be intuitive.

The widespread

popularity of “creative” in economic discourse today suggests that this old

breach between the imaginative and the productive has partly been closed. The idiosyncratic,

eccentric, even oppositional posture of the creative artist is now an economic

asset, chased by real-estate developers and promoted by self-help writers as

comparable to the spirit of the entrepreneur. The popularity of “creativity” as

an economic value in English can be traced to two major sources—Joseph

Schumpeter, 20th-century economist and theorist of “creative destruction,” and

Richard Florida, the University of Toronto scholar whose book, The Rise of the

Creative Class, became one of the most celebrated and influential urban policy

texts of the early 2000s. “The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly

revolutionizing the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of

production, and with them the whole relations of society,” wrote Marx and

Engels in the Manifesto of the Communist Party. In his 1942 classic Capitalism,

Socialism, and Democracy, Schumpeter agreed, up to a point. Schumpeter shared

Marx’s sense of capitalism as a destructive and also transformative historical

process, but he reframed Marx’s history of class struggle motivated by

exploitation as an evolutionary process driven by visionary entrepreneurs. By

opening new markets and breaking down old industrial processes, Schumpeter

wrote, capitalism “incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from

within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.”

This process is what Schumpeter called “creative destruction.”

“Creative” here refers

to the work of forging new modes of production, new markets, and new products,

but it also had a touch of artistry: the ingenuity, vision, and intuition to

make things anew. Even so, creativity still belonged more to the artists’

studio than the corner office until the last half of the 20th century in the

United States, when it came to describe a productive aspect of the psychology

of individual workers. Sarah Brouillette has shown how much the familiar

accoutrements of today’s progressive office culture—foosball tables, bright

colors, and other perks ostensibly meant to cultivate employees’ creativity and

loyalty—owe to the psychologist Abraham Maslow, famous for his 1943 theory of a

“hierarchy of human needs.” Maslow, Brouillette writes, “began imagining all

business culture as an outlet for and source of workers’ enterprising

individual self-fulfillment.” Florida’s notion of “artistic creativity,” which

he regards as integrated with other varieties (economic and technological) is

based on the presumption that “art” equals “self-expression,” a historically

specific assumption which, like “creativity” itself, is mistaken for a

universal and timeless idea.

Indeed, it is this

particularly modernist understanding of artistic work as solitary and

idiosyncratic, oriented towards the expression of the artist’s unique self,

that also came to suit US geopolitical interests in the Cold War, as many

scholars of US and Latin American modernism have shown. Rob Pope, in his

history of creativity, includes two other examples of creativity’s Cold War

deployments. The US psychologist Carl Rogers argued that a prosperous nation

like the United States needed “freely creative original thinkers,” not

ladder-climbing conformists. If the grey Soviet system encouraged the latter,

the multi-colored capitalism of the United States required creative free

thinkers. It is this perceived cultural strength, not just newer and better

weapons, that will beat Communism, J.P. Guilford argued in 1959.

Florida believes

strongly in the naturalness and timelessness of this relatively new idea,

creativity; he describes it as “what sets us apart from all other species.”

Florida elevates creative capitalists from a social type, which they remain in

Schumpeter’s theory of the entrepreneur, to a social class, one that Florida

estimates as constituting a third of the American working population. Its

members include scientists and engineers, architects and artists, musicians and

teachers—anyone, in short, “whose economic function is to create new ideas, new

technology, and new creative content.” The creative class shares certain tastes

and preferences, like nonconformity, an appreciation for merit, a desire for

social diversity, and an appetite for “serendipity,” the chance encounter

facilitated by urban life.

A taste for city life,

in fact, is one of the creative class’s most treasured preferences, and

Florida’s ideas promised to leverage these to repopulate declining urban

centers without significant public expenditure on social welfare or

infrastructure. Politicians in various postindustrial cities in the global

north became eager customers of the consultancy spawned by the success of The

Rise of The Creative Class. We will find in Florida’s account scarcely a trace

of the breach that Williams described between imaginative and productive

creativity. Creativity, Florida writes, is the “font from which new

technologies, new industries, new wealth, and all other good economic things

flow.” Art, music, and gay-friendliness are no longer independent values of

their own, but rather values dependent on their appeal to high-wage knowledge

workers.

Why creativity now?

Jamie Peck, one of Florida’s most unsparing critics, argues that from the

1970s, deindustrializing cities were faced with a dearth of available economic

development options. They began competing with one another not only for

increasingly mobile jobs, but for places in a consumer economy in which cities

became commodities themselves. Abandoning comprehensive urban planning, city

governments focused instead on what Peck calls “urban fragments” with potential

in this consumer market—single districts with marketable appeal due to their

theaters or arenas, historic architecture, proximity to job-rich downtowns, or

some other marketable feature. (Often, these urban fragments become the sort of

generic, purpose-built developments the suburban-born creatives were supposedly

fleeing, like the new creative-class Potemkin village north of downtown Detroit

with the odd name The District Detroit, an ode to urbanity that only a marketer

could love, or even understand.) The creative city becomes a place where a

mobile middle class can participate in this consumer economy as workers and

residents. Since there is a broad affinity between one’s economic and

imaginative activity in the Floridian regime of creativity, you “live, work,

and play,” in the familiar liturgy of bourgeois urban life, as an economic

subject at all hours. Even artistic activity that might have once appeared

oppositional or radical—Florida claims to be a big fan of rap music—merely

buttresses the “creative index” of the city (a metric he developed).

“Whereas classical

liberal doxa assumes that what we are and what we own must not be confused,”

writes Brouillette, neoliberals favor a “union of economic rationality and

authenticity, this perfect marriage between the bohemian and what had been her

bourgeois other.” The extra-economic values of the artist and the priorities of

the market are no longer treated as autonomous, much less antagonistic, but harmonious.

As Brouillette emphasizes, however, it would be a mistake to read the rise of

the creative class as a colonization of the once-pure realms of the artistic

imagination by the market. The rise of the so-called creative class is not a

heroes-and-villains plot of businessmen corrupting creativity. This would be

far too flattering to artists and writers, who are hardly innocent bystanders.

Rather, the business world has valorized unexamined ideas of what “artistry”

means and turned an individualistic, class-bound idea of “the artist” towards

market goals. These meanings of artistry have evolved over the years in complex

ways, but the one that circulates in the economic use of creativity dates to

the origins of the word “creativity” in the late 19th century. Then, as

Gustavus Stadler has shown, creativity was closely aligned with 19th-century

ideas of “genius” and “inspiration,” which were seen as the fruit of an

“irreducible originality,” rather than a social process. As the cult of the

entrepreneur shows, this fantasy of irreducible originality is still with us.

Sometimes, there really is nothing new under the sun.

From : Keywords: The

New Language of Capitalism. Published by

Haymarket Books, 2019.

How ‘Creativity’ became

a capitalist buzzword. By John Patrick Leary. LitHub , March 11 , 2019.

In 1959, a group of

high school juniors in a Brooklyn classroom took a very bad quiz. The

questions, written by a right-wing, pro-business lobbying group, were a mix of

multiple-choice and true-false propositions on economic matters, like When a

company makes big profits in any one year, it ought to raise wages. (Correct

answer: false.) Or: Which of the following do you think should be government

owned and operated? a) railroads b) automobile companies c) banks d) steel

companies e) oil companies f) power companies or g) none of the above. (Correct

answer: g.) Most students failed the quiz; the average score was 45 percent,

but they didn’t appear to mind much. One student told the authors of the quiz

that they represented “a stinking, reactionary organization.”

And so they did. The

quiz was written by the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), an

organization founded in 1895 to fight organized labor and retooled in the 1930s

as a leading opponent of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. After World War

II, NAM’s eager propagandists began developing free-market economics curricula

for U.S. high schools, which they were convinced were hotbeds of pro-labor and

communist sentiment. Written student feedback recorded in NAM’s files seemed to

confirm those fears. A Brooklyn student wrote on the quiz:

WORKERS OF THE WORLD UNITE!

Down with the capitalist exploiters. These ‘people’ do no work and expect to

receive recompense for laziness. To paraphrase Lincoln, who in his second

inaugural commented in much this way on slavery—‘the taskmaster wringing his

bread from the sweat of another’s brow and the unrequited toil of millions of

laborers.’ This system is contradictory to our ideals. The system must be

abolished and the worker emancipated.

The results showed the

NAM researchers the urgency of their mission. The honor students who flunked

their economics quiz were some of the city’s most elite students, and yet, the

NAM report concluded, they showed an exceptionally “high degree of economic

illiteracy.” Teaching the youth of America to love the “free enterprise system”

again would be a generational task.

Looking back from the

vantage point of neoliberal America circa 2019, it is striking (and a little

cheering) to see the anguish of the defenders of private property at

mid-century. In her 2009 book Invisible Hands, Kim Phillips-Fein showed how

deeply the fall of the “employer’s paradise” of the 1920s shook the ruling

class from the 1930s onward, as workers struck and organized and the public

mood turned against industry. By the 1950s, right-wing writers complained that

socialists still set the terms of debate and commanded the language of the

economy: “55% hold to the Marxist theory ‘from each according to his ability,

to each according to his needs,’” according to the NAM’s report on American

teenagers during the Eisenhower era. Their schoolbooks uniformly “make the

employer look like a piker,” lamented the head of the group’s education

department. “We have not learned to speak our own economic language as well as

the other fellow has learned his specious patter,” wrote Wilbur Brons in the

Chicago Journal of Commerce in 1944. Things were so bad in 1950 that Pierre S.

du Pont, scion of the Delaware chemical dynasty and one of America’s richest

men, felt himself to be living a kind of tragedy. “Perhaps,” he wrote wistfully

to a colleague, “we were born too soon.”

Exiting the

social-democratic nightmare meant, in part, learning, and teaching, a new

language. The socialistic shibboleths of “security,” “planning,” “economic

democracy,” and “full employment” would have to be confronted and countered

with new ideals of competition and entrepreneurship. People like the Brooklyn

high school juniors had learned, through years of Depression and war, to

associate freedom with security from the thing called “the market,” in its

various manifestations: a cruel boss, a closed factory gate, a sped-up assembly

line. To redeem the free enterprise system, the apostles of private property

needed a vocabulary for emancipation through the market. To do this, they

needed to make the market the sort of misty abstraction you could never confuse

with the “sweat of another’s brow.” If only Pierre du Pont could have known how

popular “innovation” would one day become.

One of innovation’s

earliest and most cogent modern definitions, in the economic usage that we’ve

wearily come to know so well, comes from Joseph Schumpeter. The Harvard

economist saw innovation in 1942 as “the entrepreneurial function.” To innovate

meant:

to reform or revolutionize the pattern of

production by exploiting an invention or, more generally, an untried

technological possibility for producing a new commodity or producing an old one

in a new way, by opening up a new source of supply of materials or a new outlet

for products, by reorganizing an industry and so on.

He wrote elsewhere that

“innovations are always associated with the rise to leadership of New Men,”

which pinpoints one of the major paradoxes of the term: its simultaneously

functional and utopian usages. That is, the process of innovation—Schumpeter

famously called it “creative destruction”—is both a workaday managerial process

and also a kind of heroic eruption of market-shaping genius. The ubiquity of

the term today may make us think of high-tech abundance, or perhaps the “better

living through chemistry” that twentieth-century American firms like DuPont

long promised consumers of plastics and nylons. But now, of course, the idea of

innovation—less moored to material things than chemistry was—reigns supreme in

Silicon Valley, the world’s “most innovative neighborhood,” as a typical

description in the business press goes. “Chemistry” implied, at some point in

the process, the production of a material object; tech innovation celebrates

the decisions of the manager in his office.

Still, where, exactly,

did this brand of innovation, in all its world-conquering glory, come from? It

is impossible to date the origins of a word, especially one as vague as this

one, with any certainty, but “innovation” as we use it now—a spirit of

market-serving managerial creativity—begins roughly in 1934. This was the year

that saw hundreds of thousands of workers across the country in a variety of

industries—from longshoremen in San Francisco and Seattle to teamsters in

Minneapolis to textile workers in Alabama—walk off their jobs in a wave of

major strikes. And in the following year, the Social Security Act and the

Wagner Act were passed, landmark pieces of the New Deal. Reacting with alarm to

these events, the nation’s evangelists for private property cast about

desperately for a response.

The New Deal’s domestic

opponents, scrambling for an edge against Roosevelt, fixed on “bureaucracy.” In

the platform of the American Liberty League (a short-lived congress of

industrialists the president eagerly denounced as “economic royalists”) the

first point was “to combat the growth of bureaucracy.” By “bureaucracy,” they

meant the Works Progress Administration, unemployment insurance, labor unions,

Social Security, and the kind of public ownership of major industries the

Brooklyn students were still prepared to endorse in 1959. The problem, of

course, was the widespread popularity of all the above. The defenders of free

enterprise were still using someone else’s terms: “freedom from bureaucracy,”

also a NAM slogan, simply riffed on Roosevelt’s “four freedoms.” What the

American right needed, in other words, was its own positive language of

“freedom” in the market.

Innovation became the

word for the job. Its very vagueness served as an irresistible selling point.

Like Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s definition of obscenity, innovation

was something that its ardent modern prophets professed to know mostly when

they saw it. And increasingly they came to see it everywhere—particularly in

the internet age’s long tail. By now, virtually any new product is described as

an innovation, but innovation in its most dominant form today is a kind of

spirit, a way of being, an attitude. This helps explain its wide distribution

across profit-making and nonprofit fields. The Harvard Business Review, the

organ of corporate conventional wisdom, defines innovation in one article as

“experimentation, risk-taking, and variety,” which are “the enemy of the

efficiency machine that is the modern corporation.” Putting a man on the moon,

putting the world on wheels, putting an encyclopedia in your pocket: these

breakthroughs are all fruits of this spirit of risk-taking. But even the most

banal, disposable products of our lives are awash in it; if, for any reason,

you find your way to www.band-aid.com, you will find there an article called “A

History of Band-Aid Brand Innovation.” (Sample achievement, 2001: “Band-aid.com

is launched.”)

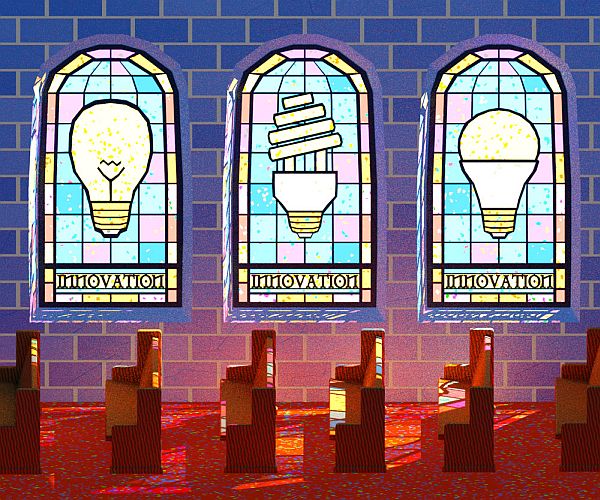

Most institutions

ritually invoke it for self-justification: Aramark Correctional Services, the

private prison food contractor implicated in Michigan for serving literal

garbage to inmates, sponsors a “Jail Innovations of the Year Award” to

recognize jailers for “innovative contributions made to their jail or

correctional facility.” Politicians of all parties invoke it reverently. There

are, by my rough count, at least a half-dozen Innovation Churches currently

operating across America, and elsewhere, a “theology of innovation” seeks to

update that decidedly old-economy metaphor of the preacher as shepherd in favor

of a new, knowledge-economy pastorate. The evangelical megachurch minister Rick

Warren, for example, has written that “a theology of innovation always reminds

us that God intends us to be creative.” Warren is speaking here of a church’s

organizational culture, and he borrows from the hipster capitalist CEOs who

advocate replacing boardrooms and cubicles with ping-pong tables and reclining

lounge chairs. Submission to God, in Warren’s church, no longer requires Job’s

prostration in the face of the Lord’s unfathomable desires. Instead, Warren

writes, “it’s when I get in a totally prone position”—he means sitting in a

recliner—“that I can be the most creative and can discover what God would have

us do.”

Our children are also

taught to be innovators, from inner-city Atlanta to affluent San Diego, and

from pre-kindergarten through college. A school in Las Vegas promises to

nurture the “entrepreneurs and creators inherent in us all,” starting with

twelve-month-olds in day care; entrepreneurship summer camps teach

middle-schoolers to write a business plan and pitch investors; colleges and

universities increasingly market themselves as laboratories of innovation and

entrepreneurship.

After factories,

prisons, schools, and churches, there isn’t much left over in twenty-first

century American life. Across these various institutions, innovation is so

widespread and its goodness so seemingly self-evident that questioning it might

seem bizarre and truculent, like criticizing beauty, science, or

penicillin—things we think of either as universal human virtues or socially

useful things we can scarcely imagine doing without. Where did this ubiquitous

concept come from—so imprecise, so vapid, in neither its verb or noun form

describing any coherent action or object with clarity or consistency? And what

does its popularity say about us?

Here the postwar usage

of the term is especially telling. Along with “entrepreneurship,” a related

term, innovation became a response to the malaise of bureaucracy typically

shorthanded by the title of William Whyte’s 1956 best-seller, The Organization

Man. Whyte argued that Americans in the fifties—by which he meant middle-class,

professional white men—were “imprisoned in brotherhood.” A stifling spirit of

consensus was sapping the country’s vital and independent energies.

Middle-class, flannel-suited office workers lost in bureaucracies and marooned

in suburbs threatened the vitality of an economy compromised by its own

stability. The old economic virtues had lost their power. What good was a

Horatio Alger story about the importance of thrift in an economy built on

endless consumption? What did “pluck” matter to a middle manager?

The college-educated

youth of the late 1950s were interested in job security, not trailblazing,

Whyte argued. He quotes an economics professor who says his students “do not

question the system. . . . They will be technicians of the society, not

innovators.” In an example of the evergreen nature of blaming social problems

on Kids Today, a youth marketer lamented in 1960 that young men were not the

“pioneer stock” of their grandparents. “I think that a lot of large corporation

heads know it and are alarmed about it,” he said. “They get the organization

man rather than the entrepreneur.” One of the first articles centered on the

topic of innovation in the Harvard Business Review, from 1962, echoed this

suspicion of the “technician” as a compliant facilitator, rather than a dynamic

creator. “In our striving to create and maintain order and stability in large

enterprises,” wrote John J. Corson in “Innovation Challenges Conformity,” “it

has become increasingly clear that we discourage and limit the initiative and

creativeness required for innovation.”

Free enterprise, then

the most popular euphemism for capitalism, described a system and a structure;

innovation was becoming a way to describe a free individual’s way of thriving

inside that structure. Advocates of the new discipline of management began to

emphasize what the MIT business professor Douglas McGregor called in 1960 “the

human side of enterprise”—moral and personal traits like empathy and

innovation, instead of classic administrative traits like discipline and

authority. In his 1954 book The Practice of Management, Peter Drucker, an

Austrian exile often called the “father of management theory,” described the

calling of managers as nothing less than to integrate operations “so as to

utilize the special properties of the human being.”

Drucker, beginning with

his 1939 book The End of Economic Man, was preoccupied by the organization as a

cultural and political problem—he argued that a fetish for organization as such

defined the appeal of Nazism. But in his 1985 book, Innovation and

Entrepreneurship, Drucker sounded an optimistic note. “Where are all the young

people who, we were told fifteen years ago, were turning their backs on

material values, on money, goods, and worldly success, and were going to

restore to America a ‘laid-back,’ if not a pastoral ‘greenness’?” For the

management theorists who came to prominence in the 1960s, the business world

was not the place of one-dimensional men, from which laid-back eccentrics fled.

Quite the contrary: “innovation” was the recovery of the more fully human, the

irrational, the creative, the idiosyncratic in business and in all aspects of

culture influenced by it (which was, Drucker argued, every sphere of human

culture). And so innovation could offer a sense of purpose to workers swallowed

by bureaucratic consensus. As Nils Gilman has argued about Drucker, practical

business advice—the workaday techniques of innovation and

entrepreneurship—became the solutions to the crises of capitalism that erupted

violently at the beginning of Drucker’s career. The innovator, as Schumpeter

had said, was both bureaucrat and hero.

This sort of idealism

still resounds in the vocabulary of the business world today: it is

individualized, moral qualities of innovation and “passion” that ostensibly

drive success, and whimsical fetishes like “leadership” and “design thinking”

package a species of individual deliverance in a cubicle. The freedom from

bureaucracy and order-following that innovation came to promise belongs to what

Drucker called in 1968, with now-quaint optimism, “the knowledge economy.” This

was an economy driven by “ideas, concepts and information rather than manual

skill or brawn.” No longer a rule-following drone in the industrial society,

the worker in the knowledge economy was driven by her independent choices. We

have moved on from an economy of “predetermined occupations into one of choices

for the individual,” Drucker claimed. The knowledge-economy worker can make a

living doing “almost anything one wants to do and plying almost any knowledge.”

“This,” Drucker insisted, defying the biblical warning, “is something new under

the sun.”

For the historian of

such an idea—the supposedly ageless idea of newness itself, of creativity, of

human initiative—the warning in Ecclesiastes against hubris makes a great deal

of sense. What is very old in the literature of business, self-help, and corporate

public relations is constantly made new again. Theirs is a history of expired

prophecies and long-defunct game-changers: from “quality circles” and mind

cures to synergy and emotional intelligence, the fantasy of the

transformational new idea—the better intellectual mousetrap—has long seduced

writers chasing riches and prestige by telling others how to chase riches and

prestige. For example, the number of articles, books, and lectures asserting

that no, “innovation” is not the same as “invention,” might suggest that the

issue has been definitively settled. But business literature is also a history

of endless repetition, of already thin gruel reheated and sold—and sold, and

sold, in a vast publishing market—as fresh nourishment. Innovation, in fact, is

one such example. It’s one of the oldest new ideas in the corporate lexicon, a

novelty that never ages. Forty years after Schumpeter praised the “creative

destruction” of the innovative entrepreneur, the management consultant and

best-selling author Tom Peters paid tribute to these hero-functionaries in his

book In Search of Excellence—the most widely held monograph among libraries in

the United States from 1989 to at least 1997, according to the library database

WorldCat. “Small, competitive bands of pragmatic bureaucracy-beaters,” he

called the apostles of excellence, “the source of much innovation.”

Because it is an ideal

of managerial decision-making, innovation is critical to a vernacular of

neoliberalism that renders invisible most forms of labor performed by most

people on Earth—hot, fast, exhausting, repetitive, alienating, caretaking,

unwaged. Its emergence in the 1950s and 1960s was conditioned by mass culture

and the legacy of the New Deal. Influential theories of entrepreneurship and

innovation in these decades were also invested in questions about the fate of

the non-white world, which was poised as never before to disrupt the world

system.

Drucker said that what

distinguished an “‘underdeveloped country’—and keeps it underdeveloped—is not

so much a shortage of capital as it is shortage of innovation.” Walt Rostow,

the best-selling political theorist whose 1952 book, The Process of Economic

Growth, was an argument for the steps an underdeveloped society needs to “take

off” into development, listed a willingness “to accept innovations” as a major

criteria. This helps explain how “innovativeness” can become a measure, not

just of an industry’s profitability, but of social worth and national

character. When The Economist last October defended the Honduran migrants who

were confronting Trump at the southern U.S. border, they did not invoke civil

rights, the dignity of the individual, or pan-Americanism. They spoke, instead,

of the danger to “American dynamism and innovation.” Central American migrants

include valuable fruit-pickers and home health aides but they can also be

“entrepreneurs and coders,” useful resources for American industry. If

innovation is, as Jill Lepore has argued, the nineteenth-century ideal of progress

“scrubbed clean” of its horrors and “relieved of its critics,” this is once

again proof that Ecclesiastes was probably right: there is nothing new under

the sun.

But in the years since

Rostow, Drucker, and even Tom Peters theorized the mystic inner workings of

innovation, the term has taken on a more abstract, even metaphysical cast. The

Harvard Business School luminary Rosabeth Moss Kanter asserts that “to create a

culture in which innovation flourishes takes courage,” and advises the

courageous to put “innovation at the heart of strategy, and tout it in every

message.” It can also take the form of incantatory rituals (to become more

innovative, management consultant Abhijit Bhaduri suggests “weekly

conversations with millennials to understand how they dream”) and Orientalist

fantasies (one former Microsoft executive listed his job title as “Innovation

Sherpa” on his LinkedIn profile, and the title of “innovation guru” abounds in

the world of business consulting). Often it takes the puzzling form of

tautology. To be more innovative, says Harvard Business School professor

Clayton Christensen, the most revered prophet of the gospel of “disruptive

innovation,” you have to “‘think differently,’ to borrow a slogan from Apple.”

But Christensen here refers to a slogan that advertises Apple’s capacity for

innovation, which lies precisely in the company’s alleged ability to, uh, think

differently. In other words, Christensen is arguing that to innovate, you have

to be innovative. Tautological certainties like this abound in tech-industry

and innovation discourse, whose proselytizers wander in closed conceptual

circles in which capitalism, or a world and a history outside of it, is never

imagined, much less questioned. Where these modern prophets of the innovation

gospel originally hailed it as the means by which capitalism reinvented itself,

and disrupted ossified markets and backward social practices, the innovator’s

prerogative has gradually morphed into the self-evident aim of capitalist

development.

And this means, much

like other varieties of secularized worship, the innovation cult accrues

greater complements of unquestioned social power. The brand of innovation is

everywhere and nowhere. Primary schools, liberal arts colleges, and business

schools all claim to nurture it; entire airports could be filled with the

business-advice tomes that have claimed to teach it; municipal, state, and

federal governments compete to subsidize it; and there are few products that

are not advertised to the consumer as delivering the taste, sound, or

experience of it.

Back here in the

actually existing social world, though, the widespread circulation of the

innovation ideal allows us to employ it as a sort of marker to track the major

distinguishing features of contemporary capitalist ideology: its celebration of

knowledge, rather than labor, as the driving force of the world economy; its

ostensible disdain for hierarchy and bureaucracy; its unskeptical celebration

of technology; and its reframing of the loss of job “security” as the laudable

increase of “flexibility.” The innovator who emerges from this complex history

is a contradictory figure defined by an oscillation between what seem like

contradictory poles: imagination and production, rebellion and convention,

progress and reaction, the common good and private wealth. These paradoxes,

too, are part of the idea’s power, since the underlying vagueness of

innovation-for-innovation’s sake permits it to mean all things to all people.

It cultivates the open-ended creativity typically identified with the artist,

and turns it to profit-making ends, and cultivates it in large firms; it is the

twenty-first century’s theory of progress, but it is a heroism of office work.

It is a theory of novelty that is perpetually repeating itself. And in its

political origins, it is a theory of the new for those outraged by the New

Deal.

Its current power

shows, however, that the leaders of NAM were on to something. To change the way

people think about capitalism, you have to start with how they talk about it.

The Innovator’s Agenda. By John Patrick Leary. The Baffler ,

March 4, 2019.

When General Motors

laid off more than 6,000 workers days after Thanksgiving, John Patrick Leary,

the author of the new book Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism, tweeted out

part of GM CEO Mary Barra’s statement. “The actions we are taking today

continue our transformation to be highly agile, resilient, and profitable,

while giving us the flexibility to invest in the future,” she said. Leary added

a line of commentary to of Barra’s statement: “Language was pronounced dead at

the scene.”

Why should we pay

attention to the particular words used to describe, and justify, the regularly

scheduled “disruptions” of late capitalism? Published last week by Haymarket

Books, Leary’s Keywords explores the regime of late-capitalist language: a set

of ubiquitous modern terms, drawn from the corporate world and the business

press, that he argues promulgate values friendly to corporations (hierarchy,

competitiveness, the unquestioning embrace of new technologies) over those

friendly to human beings (democracy, solidarity, and scrutiny of new

technologies’ impact on people and the planet).

These words narrow our

conceptual horizons — they “manacle our imagination,” Leary writes — making it more

difficult to conceive alternative ways of organizing our economy and society.

We are encouraged by powerful “thought leaders” and corporate executives to

accept it as the language of common sense or “normal reality.” When we

understand and deploy such language to describe our own lives, we’re seen as

good workers; when we fail to do so, we’re implicitly threatened with economic

obsolescence. After all, if you’re not conversant in “innovation” or

“collaboration,” how can you expect to thrive in this brave new economy?

Leary, an English

professor at Wayne State University, brings academic rigor to this linguistic

examination. Unlike the many people who casually employ the phrase “late

capitalism” as a catch-all explanation for why our lives suck, Leary defines

the term and explains why he chooses to use it. Calling our current economic

system “late capitalism”suggests that, despite our gleaming buzzwords and

technologies, what we’re living through is just the next iteration of an old

system of global capitalism. In other words, he writes, “cheer up: things have

always been terrible!” What is new, Leary says, quoting Marxist economic

historian Ernest Mandel, is our “belief in the omnipotence of technology” and

in experts. He also claims that capitalism is expanding at an unprecedented

rate into previously uncommodified geographical, cultural, and spiritual

realms.

Keywords was inspired

by a previous work of a similar name: the Welsh Marxist theorist Raymond

Williams’s 1976 book Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Williams’s

goal, like Leary’s, was to encourage readers to become “conscious and critical”

readers and listeners, to see the language of our everyday lives “not a

tradition to be learned, nor a consensus to be accepted, [but as] . . . a vocabulary

to use, to find our own ways in, to change as we find it necessary to change

it, as we go on making our own language and history.” Words gain their power

not only from the class position of their speakers: they depend on acquiescence

by the listeners. Leary takes aim at the second half of that equation, working

to break the spell of myths that ultimately serve the elites. “If we

understood... [these words] better,” Leary writes, “perhaps we might rob them

of their seductive power.”

To that end, Leary

offers a lexicon of about 40 late capitalist “keywords,” from “accountability”

to “wellness.” Some straddle the work-life divide, like “coach.” Using simple

tools — the Oxford English Dictionary, Google’s ngram database, and media

coverage of business and the economy— Leary argues that each keyword presents

something basically indefensible about late capitalist society in a sensible,

neutral, and even uplifting package.

Take “grit,” a value

championed by charter school administrators, C-suite execs, and Ted Talkers. On

the surface, there’s nothing objectionable about insisting that success comes

from hard work sustained in spite of challenges, failure, and adversity. It can

even seem like an attractive idea: who doesn’t want to believe, as author of the

bestselling Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance Angela Duckworth puts

it, that success rests “more on our passion and perseverance than on our innate

talent” — or the race and income of our parents?

What discussions of

“grit” scrupulously avoid, Leary writes, is “the obviously central fact of the

economy”: poverty. Duckworth and other proponents of grit nod to the limited

horizon of opportunity presented to those living in poverty, but insist that

grit can help people “defy the odds.” Implicitly, they accept that most will

fail to do so: they simply promise elevation to the hard-working, the

deserving, the grittiest — that is, to the very few.

“Grit offers an

explanation for what exists,” Leary writes, “rather than giving us tools to

imagine something different.” Rather than attacking the conditions that make

“grit” necessary, the word’s proponents ask women, people of color, and the

poor to overcompensate for the unjust world into which they’ve been born. While

the need for “grit” is most often preached to urban schoolchildren and people

in poverty, its “real audience,” Leary writes, is “perched atop the upper

levels of our proverbial ladder,” a position from which inequality doesn’t look

so bad.

Leary divides his

keywords into four broad categories: first is “late-capitalist body talk,”

which imbues corporations with the attributes of human bodies, like nimbleness

or flexibility, and shifts focus away from the real human bodies whose labor

generates its profits. “Much of the language of late capitalism,” Leary writes,

“imagines workplaces as bodies in virtually every way except as a group of

overworked or underpaid ones.”

Then there’s the “moral

vocabulary of late capitalism,” which often uses words with older, religious

meanings; Leary cites a nineteenth-century poem that refers to Jesus as a

“thought leader.” These moral values, Leary says, are generally taken to be

indistinguishable from economic ones. “Passion,” for example, is prized for its

value to your boss: if you love what you do, you’ll work harder and demand less

compensation. Some are words, like “artisanal,” that reflect capitalism’s

absorption of the countercultural critique that it failed to provide workers

with a sense of purpose and autonomy. Finally, there is the category of words

that reflexively celebrate the possibilities of new technologies, like “smart”:

smart fridge, smart toaster, smart toilet.

As Leary shows, these

keywords reflect and shore up the interests of the dominant class. For the tech

overlords of Silicon Valley, an “entrepreneur” is someone innovative and savvy,

who “moves fast and breaks things.” The entrepreneur alone creates his

company’s exorbitant wealth — not his workers, nor any taxpayers who may fund

the innovations his company sells. (Elon Musk, for example, has received nearly

$5 million in government subsidies). It’s a very useful concept for

billionaires: after all, why redistribute that wealth, through taxes or higher

wages, to those who didn’t create it?

In these short essays,

Leary undermines what Soviet linguist Valentin Voloshinov describes as the aim

of the dominant class: to “impart an…eternal character to the ideological sign,

to extinguish or drive inward the struggle between social value judgements

which occurs in it. ” And in the case of “entrepreneur,” for example, Leary

shows that quite a lot of struggle between social judgements is contained in

the word.

First defined around

1800 by French economist Jean-Baptiste Say as one who “shifts economic

resources . . . into an area of higher productivity and greater yield,” the

word was given a dramatically different inflection by political economist

Joseph Schumpeter. According to Leary, our contemporary view of

entrepreneurship comes from Schumpeter, who believed that the entrepreneur was

“the historical agent for capitalism’s creative, world-making turbulence.” When

we talk about “entrepreneurs” with an uncritical acceptance, we implicitly

accept Schumpeter’s view that wealth was created by entrepreneurs via a process

of innovation and creative destruction — rather than Marx’s belief that wealth

is appropriated to the bourgeois class by exploitation.

By demonstrating how

dramatically these words’ meanings have transformed, Leary suggests that they

might change further, that the definitions put in place by the ruling class

aren’t permanent or beyond dispute. As he explores what our language has looked

like, and the ugliness now embedded in it, Leary invites us to imagine what our

language could emphasize, what values it might reflect. What if we fought “for

free time, not ‘flexibility’; for free health care, not ‘wellness’; and for

free universities, not the ‘marketplace of ideas”?

His book reminds us of

the alternatives that persist behind these keywords: our managers may call us

as “human capital,” but we are also workers. We are also people. “Language is

not merely a passive reflection of things as they are,” Leary writes. “[It is]

also a tool for imagining and making things as they could be.”

Talk

with John Patrick Leary on his book. RisingUp With Sonali, February 15 , 2019

More on John Patrick

Leary’s website Keywords for Capitalism

No comments:

Post a Comment