“Images, moods, a feeling for the

place,” Peter Zumthor said in an interview, when asked what inspires him.

Born on April 26, 1943, Zumthor grew

up near Basel. Following an apprenticeship as a cabinet maker, he studied

interior design and architecture at the School of Applied Arts in Basel and the

Pratt Institute in New York.

In 1979, after working as a building

and planning consultant for canton Graubünden in eastern Switzerland, Zumthor

established his own practice in Haldenstein, where he still works.

He was a professor at the University

of Italian-speaking Switzerland’s Academy of Architecture from 1996-2008 and

has also held visiting professorships at several international universities,

including the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

He has received numerous prizes,

including the Mies van der Rohe Award for European Architecture (1998), Japan’s

Praemium Imperiale (2008), the Pritzker Architecture Prize, often called the

“Nobel Prize of architecture”, (2009) and the Royal Institute of British

Architects’ Royal Gold Medal (2012).

In 2017, he received the lifetime

award from the Association of German Architects, the first non-German to

receive the prize. “His consistent focus on the idea of light, material and

space – plus his meticulous attention to detail and quality – give his work a

timeless relevance,” the association said.

Despite the accolades, Zumthor has

said he aims to create buildings that become part of everyday life so that even

people who don’t consider their architectural merit can enjoy them.

Peter Zumthor turns 75: a dip into

atmospheric architecture. By Thomas Kern (picture editor), Thomas Stephens

(text). Swissinfo, 2018

Peter Zumthor, the Swiss architect

behind the new Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), explains how hard it

is to accept democratic processes.

Besides his work on LACMA, he is

planning his first high-rise in Belgium. On July 1, Zumthor was awarded this

year's prestigious BDA Grand Award in Germany.

This is what the German jury for the

BDA prize had to say about the Swiss architect: "His work takes

architecture back to humanity's 'original creations'." Better than anyone,

it says, this self-confident hermit knows "what building and sheltering

originally meant". Zumthor has also won the coveted Pritzker prize for

architecture. . His commitment to quality and attention to detail, they say,

"give his work timeless validity".

SRF: What inspires you?

Peter Zumthor: Images, moods, a

feeling for the place. That also includes listening, finding out what the

client wants and what the assignment requires. And picking up discordant

elements as well. Sometimes I have to ask: Is that really what you want?

Naturally I always take great pleasure in location. Building houses that

contribute to the quality of the location just by being there, that somehow

improve or endorse it: that is my great passion. Perhaps even making something

visible that had been lost to sight, a piece of the location’s lost history.

SRF: How about building bridges?

Would that also be something you could do?

P.Z.: I can't, but I love bridges.

I've just seen a picture of the new Tamina Bridge, a lovely arch bridge. I'd

love to design buildings with the same logic. With the loveliness that is

created by the logic of their design. The building in Los Angeles that I'm

currently working on has something of a huge bridge about it, with its enormous

pillars. That’s why I’m working on it in close cooperation with engineers. It's

a fantastic collaboration, because we talk about the building's structure and

statics.

SRF: There's an interplay of light

and shade in your buildings that you call "calm space". What's that?

P.Z.: Sometimes you come across

films or books that make you feel the author is constantly showing off how

great he is. That's not my style. I like to blend into the background, so that

people come to love the building as time passes.

SRF: What aspect of project work do

you most enjoy?

P.Z.: Building is great. Watching

20, 200 or 2,000 people create something, seeing how all their skills are

needed – that makes me proud. And the pleasure it gives me is like that of a

conductor able to work with a variety of instruments. The beginning is lovely

too. It's always the initial idea that's most exciting. And that excitement is

what keeps you going as an architect throughout a long process, a process that

you must get through no matter what difficulties you encounter along the way.

SRF: How do you deal with failure?

P.Z.: I had to learn that failing

goes with the job. Nobody told me that. There are awful moments. When I had to

watch the first stair towers of the Topography of Terror museum in Berlin being

demolished, I had tears in my eyes. And I sometimes despair of certain Swiss

democratic processes.

SRF: One of your key works is the

Vals spa complex. Your attempt to buy it was unsuccessful: the municipal

assembly accepted another offer. What do you think of that now?

P.Z.: In retrospect, I'm glad it

didn't come off.

SRF: The plan now is for a 300-metre

tower by Thom Mayne in Vals. What do you think of this project?

P.Z.: Thom Mayne is a good,

interesting architect. Twenty-five years ago, we taught together at a

university in Los Angeles. I was most impressed by him. He often used to say

things in response to criticism that I didn't understand at all – and when I looked

round, I could see that our colleagues and the students didn't understand what

he meant either. Los Angeles has several fantastic buildings of his. But this

commission [for the Vals tower] involves a setting he is totally unfamiliar

with. A gigantic tower in a mountain village? I have to say no.

SRF: A project for a music hotel in

Braunwald was recently turned down by the municipal assembly, and it's now

hanging in the balance. What do you think of that?

P.Z.: It's the same problem: you

have to be patient. The vote wasn't about the hotel itself, it was about the

water plan – though the two were connected. The town now has the opportunity to

put the project back on the rails, and in an improved form. I still believe in

it.

SRF: You are currently working on

the LACMA, a $600 million project scheduled to begin construction next year.

How do you handle your activities abroad? Is it all done from your office in

the village of Haldenstein in Graubünden?

P.Z.: First: I need clients who

enjoy working with me through a process that will give us more knowledge at the

end than we had at the beginning. I don't implement existing ideas. I need

people who get their kicks from developing something together. That's what I

have in Los Angeles, and elsewhere too. There's no other way.

Second: communication has become

incredibly easy. I can send the largest plan flyers to Los Angeles or New York

simply by pressing a button. Putting a large team together is wonderfully

simple too. It doesn't matter where you are. The architect has to be in a place

where he can do good work, and for me that's Haldenstein.

SRF: You work like a small

architectural practice. Every project goes through you.

P.Z.: I create architectonic

originals. I can't deliver things under a company name. I enjoy inventing

buildings down to the last screw. But they don't have to be small, they can

also be large.

SRF: Does a relationship persist

between you and the building?

P.Z.: It may be like with children.

But they belong to other people. I can't visit them, I can't simply go there

even though I'd like to. I'd have to go there in secret or at night. But

there's also fear of contact. I don't like being in places where people look at

me and whisper: look, that's Zumthor.

SRF: In 2009 you were awarded the

Pritzker Prize for your life's work, the highest accolade an architect can

achieve. What effect did that have on you?

P.Z.: It helped me to be even

calmer. Throughout my career, I could never complain about not being

recognized. I always have been. There have always been people who saw what I

was doing and what was important to me. And there have always been others who

stuck a label on me: Zumthor – difficult, pig-headed. You just have to put up

with it.

SRF: Did this recognition put you

under pressure to perform at the same level?

P.Z.: No, the Pritzker Prize is just

the wrapping. On the inside, nothing has changed. Inventing every building from

the ground up, pursuing the idea to the very end and putting it into practice

in the construction sector as well as politically and culturally – it always

starts at square one, and it's always the same challenge. That doesn't change.

Once again, I'm uncertain, once again I haven't a clue, and I say: "Damn

it, something's not right, what's the matter?" And I talk to my people

about it.

SRF: Even before you were awarded

this prize, people talked of you as a "star architect".

P.Z.: I don't like that. I have

absolutely no pretensions to stardom. The existence of star architects does

architecture no good. I'd prefer it if there were star plumbers.

SRF: Art galleries, sacred

buildings, spas, barracks: is there anything else that Peter Zumthor would like

to design?

P.Z.: At the moment, we're looking

at whether we can build a high-rise in the south of Antwerp. The problem with

all high-rises is that they don't know how to deal with people at the base, or

how they should be entered. We want to find a solution that will benefit both

the town and the park. I'd like to build something on the shore, with a wide

horizon.

SRF: And when you decide you don't

want to carry on, will that mean the end of the Peter Zumthor architectural

practice?

P.Z.: I don't want to compare myself

with Alberto Giacometti, but since his death there have been no more

Giacomettis.

Architect Peter Zumthor : ‘I had to

learn that failing goes with the job’ By Silvio Liechti, Radio SRF. Swissinfo , July 7,

2017

Of interest :

Therme Vals spa has been destroyed

says Peter Zumthor. By Jessica Mairs. Dezeen , May 11 , 2017

Peter Zumthor releases latest LACMA

renderings after $150 million funding boost. By Dan Howarth. Dezeen , November 1, 2017

Peter and Annalisa Zumthor have just

returned from a seven-hour hike across the mountains and valleys of southern

Switzerland and are winding down with the neighbours over a bottle of wine.

It’s quite normal for Swiss folk to embark on such a trek on the weekends, and

the walks are one of the reasons why the Zumthors built themselves a second

home in the hamlet of Leis, a treacherous 2km road journey from Vals, the

famous spa town. All around are snow-topped mountains, shadowy pine forests,

tinkling streams and patchworks of wild flowers. Zumthor ambles over to the

picture window in the kitchen to show off the view. He spots a cluster of black

insect eggs on the glass and stops to examine them for a minute or two:

‘Beautiful, non?’ he says, before shrugging his shoulders at the splendour of

it all. Nature informs a large proportion of his work – nature and the way man

responds to it – and of all the places in which to seek inspiration, it doesn’t

get much better than here.

His house, or rather, houses (there

are actually two of them, but one is rented out) stand one above the other on a

tricky mountainside plot. He fondly refers to them as ‘a brother and a sister’.

They are a modern interpretation of the 18th-century timber houses that define

Leis, without the bad bits. ‘The old houses have tiny windows and you can’t

stand in the bedrooms,’ says the 6ft-plus Zumthor who designed his houses with

vast windows and high ceilings that will accommodate those above Hobbit height.

Swiss law insisted on traditional

slate roofs, which he paired with sleek metal chimneys, guttering and

drainpipes. ‘Also,’ continues Zumthor, ‘wood shrinks. The cupboards and doors

and stairs need to know that the walls holding them up will shrink, so I had to

build in a tolerance for this. It was very complicated,’ he says, stroking the

spots where the pine beams have already developed hairline splits now that the

house is almost two years old. ‘I’m not worried. I expected it.’

‘During the night you can hear the

house move,’ adds Annalisa, for whom, in a touchingly romantic gesture, the

houses were built. The couple have been married for 39 years and have three

children and three grandchildren. ‘In the early days, when we went on holiday

in Italy or elsewhere, we were always hunting for a place we could turn into a

holiday home,’ says Annalisa. ‘I had always wanted to live in a wooden house,

and while I was director of the thermal baths in Vals [which her husband also

built], I came across the plot.’Her husband then set about sourcing an

elaborate array of woods for the houses: combinations of local pine for the

exteriors, Canadian maple for the floors, Swiss maple for the ceilings, birch

for the cabinetry, German teak in the bathrooms and, for Annalisa’s walk-in

wardrobe, a knotty mountain wood from her home valley, ‘which has a special

smell that reminds her of her childhood.’ On the façade of each house is an

abstract motif inspired by the traditional carvings of birds and flowers that

appear on the beams of old local houses.

Inside architect Peter Zumthor’s

wooden holiday home in the Swiss Alps. By Emma O’Kelly.

Wallpaper, December 13, 2012

Swiss

architect Peter Zumthor has completed his Secular Retreat – a Living

Architecture holiday home designed to celebrate the landscape like the villas

of his hero, Andrea Palladio.

The house,

which has been more than 10 years in the making, is Zumthor's first permanent

building in the UK. It is located on a hilltop in South Devon, England, where

it commands an impressive view of the surrounding countryside. Zumthor designed

the house to be built from concrete rammed by hand – a technique that gives

stripes to the walls, both inside and out.

The thickness

of this material is revealed by the large, deep window openings, designed to

take full advantage of the setting.

“I would like

to say I'm building here in the tradition of Andreo Palladio," said

Zumthor during a tour of the building. "I don't want to compare myself

with this Renaissance architect, who has always been a favourite of mine, but

what he did was build villas for the summertime."

Zumthor said

his aim was to emulate "the incredible presence of materials, and the

beautiful command of space, light and shadow" of Palladio's designs. "I

think it is beautiful if you can make a strong building that helps you, not

which oppresses you," he said.

Secular

Retreat is the seventh house built for Living Architecture, a property rental

company set up by writer Alain de Botton to offer people the opportunity to

rent a house designed by a renowned architect. It was actually one of the first

to be commissioned. But it took far longer to be completed than any of the

others, which include MVRDV's Balancing Barn, John Pawson's Life House and A

House for Essex by FAT and Grayson Perry.

One reason

for the long delay is the level of detail and craftsmanship that went into the

building.

The rammed

concrete walls had to be created in layers – each line marks a day's work –

while the limestone floors were designed in a bespoke pattern, tailored exactly

to suit the dimensions of every slab that came from the quarry. Every broken

slab resulted in a rework. "I have this concept – I produce

originals," Zumthor told Dezeen. "My work is always my work, it is

not the work of my collaborators. I am not a trademark, I always produce an

original."

The layout of

the house is very simple, all organised on one storey. There are two wings –

one containing two bedrooms, the other containing three – and each bedroom has

its own en-suite bathroom. Where the two wings meet is a generous living space,

including a bespoke kitchen, a lounge area surrounding a fireplace, plus a

couple of quiet seating areas where occupants can enjoy solitary activities

like reading or listening to music.

Almost all of

the furniture was designed by Zumthor, including the wooden dining table,

seating upholstered in purple fabric and camel-hued leather, and the small pink

stools in the bedrooms.

Overhead, the

concrete roof sits appears to hover just above the concrete columns, raised by

a concealed steel structure within. Its surface is coloured by the wooden

formwork that the concrete was cast against – an effect that Zumthor said he

hated initially, but has grown to love.

"You

have a central communal space under a big roof, and you have five bedrooms each

with their own bath," said the architect. "So in the back it is like

a hotel, and here it's all together, you cook, you do everything

together."

Zumthor

famously keeps his studio small and turns down many commissions offered to him.

He rarely builds single houses – most of his previous projects are public

buildings, such as the Therme Vals spa in Switzerland, the Zinc Mine Museum in

Norway and the Brother Klaus Field Chapel in Germany. He said he couldn't

resist this opportunity to build on this site. "It's easy to build a nice

house here," he said.

The building

sits on the site of a demolished house from the 1940s. A few details from the

old property remain – a hexagonal patio beyond the kitchen, and a set of Monterey

pine trees that are now 20 metres tall. But Zumthor claims his house will age

much better than its predecessor: "This building frames view and

celebrates the place, the old building did not."

The house

will be available for short-term lets later this year. The architect is also

hoping to convince Living Architecture to change the name, from Secular Retreat

to Chivelstone House. "I would prefer it!" he said.

Peter Zumthor

completes Devon countryside villa "in the tradition of Andrea

Palladio" By Amy Frearson Dezeen

, October 29, 2018

Architects

may be limited in their power to prevent climate change, says Peter Zumthor,

but they can help by designing buildings to last for centuries rather than

decades.

Zumthor spoke

to Dezeen on a tour of his recently completed Secular Retreat villa – a

concrete and glass holiday home in Devon, England.

The tour took

place shortly after the UN issued the warning that we have just 12 years to

reverse the impact of global warming, to prevent global catastrophe.

The Swiss

architect said the issue was on his mind, but that he didn't feel he had much

power to make a difference. "I am

aware of these things, but I can only do so much," he said. "What I

do, I do simple buildings," he continued. "In my modest way, it is a

big concern."

One thing

Zumthor said he tries to do, to make his buildings more sustainable, is to

ensure that they will look and function in 100-200 years time. This was the

case with Secular Retreat, he explained. "We started, in a way, by

supposing that in 200 years time it is still in good condition," he

explained. "It's the opposite of the fashion shop, changing its interior

design every half year. In that sense, there's an ecological element."

"I think

these materials we're using here produce a nice ruin," he added. "All

the materials are very basic: wood, stone, steel. The only thing I don't know

about here is the glass, how this three-layered glass will hold up. That's the

price you pay to have large windows."

Another way

that Zumthor tries to reduce his carbon footprint, he said, is by avoiding

international travel whenever possible. The architect is based in Haldenstein,

a mountain village in eastern Switzerland. As well as his UK villa, the

architect's current projects abroad include an extension to the Los Angeles

County Museum of Art.

"It's

also a big concern that I have to fly around the world to do my work," he

told Dezeen."But what happens now is that modern IT helps me to avoid

flights, so I can communicate with LA and New York and San Francisco at the

same time, and we can look at the same plans at the same time." Peter

Zumthor is one of the most respected architects in the world, known for

buildings including the Therme Vals spa in Switzerland, the Zinc Mine Museum in

Norway and the Brother Klaus Field Chapel in Germany. He was awarded the

Praemium Imperiale in 2008, the Pritzker Prize in 2009 and the RIBA Gold Medal

in 2013.

The architect

is famously selective over the commissions he accepts, allowing him to keep his

studio small. "I get asked to do lots of commercial work and I have to say

no, in a friendly way," he said. To date, no building he has completed has

been demolished

"I can

only do so much" to protect the environment, says Peter Zumthor. By Amy

Frearson. Dezeen , October 29, 2018.

Also of

interest :

A Timely

Remembrance For Witch Hunts Of The Past by Louise Bourgeois and Peter Zumthor.

A pilgrimage

to visit Louise Bourgeois and Peter Zumthor’s Norwegian memorial made for

victims of the witchcraft trials hits home. By Karen Gardiner, Hyperallergic

, October 25, 2018.

A

collaboration between the late artist Louise Bourgeois (1911 – 2010) and

architect Peter Zumthor (1943 – ), the Steilneset Memorial (2011) commemorates

the 91 people (77 women and girls, and 14 men) who were executed during the

17th-century trials, mostly by burning at the stake. More people in the

Finnmark region — then home to only around 3,000 people or 0.8 percent of

Norway’s population — were executed for witchcraft than anywhere else in

Norway, which accounted for 19 percent of all Norwegian trials and 31 percent

of all death sentences. The memorial sits on the very site, off the shore of

the freezing Barents Sea, where it is believed the condemned were burned.

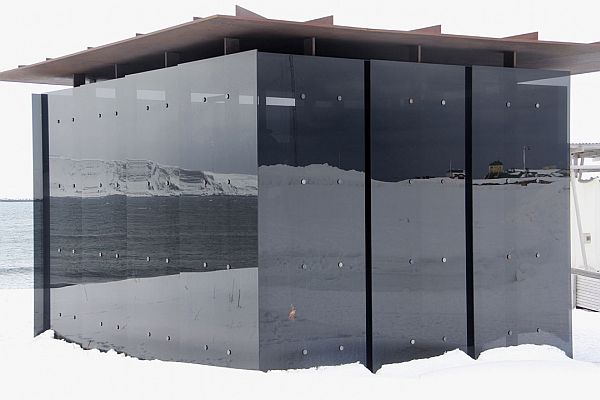

The memorial

is made up of three components, art, architecture, and history. Zumthor’s

400-foot-long oak-floored pavilion — swathed in sailcloth and lit by light

bulbs hanging in each of the 91 steel-framed windows — leads toward a steel and

smoked-glass box. Inside, sits Bourgeois’s sculpture, “The Damned, The

Possessed and The Beloved.” It is

unsparingly literal, a burning steel chair encircled above by large oval

mirrors.

No comments:

Post a Comment