Meret

Becker on Lotte Laserstein

Meret

Becker is convinced that she has already lived in another time - as a figure in

a work by Lotte Laserstein. She takes a look back at the artist's life in

Berlin in the 1920s and 1930s, the years before Laserstein was exiled. Meret Becker is convinced that she has

already lived in another time - as a figure in a work by Lotte Laserstein. She

takes a look back at the artist's life in Berlin in the 1920s and 1930s, the

years before Laserstein was exiled.

UP

CLOSE: In this series of short films, nine actors each look at one of the

artists from the exhibition “CLOSE-UP”. Approaching the subject, they share

their impressions in their own way and in their own words. The result, in each

case, is a very personal portrait of the artist that says as much about the

speaker as about the subject.

Fondation Beyeler, September 18, 2021

Lotte

Laserstein's painting entitled Self Portrait with a Cat (1928) may be regarded

as exposing a range of information about its creator, even for the casual

observer. When creating this realist painting, the German-Swedish artist

captured not only a detailed likeness of herself but carefully constructed the

work to express much about her stance in life, in addition to her role as an

artist.

The

self-portrait was intended, of course, as a form of representation to project

meaning on character, identity and status. For women particularly, creating

images of themselves in the genre of painting has been a historically arduous

task, as gendered assumptions and cultural limitations had to be ingeniously

surmounted.

Yet, in

her self-portrait Laserstein boldly confronts expectations. While both

capturing and captivating the viewer with her direct gaze, her portrait was not

a simple echo of the self but offered a challenge to perceptions of both 'the

female artist' and womanhood itself. The work, in turn, was indicative of

Laserstein's approach to the expression of her art and in her life more

generally.

Born in

Preussich-Holland in Prussia during 1898 into a family of part Jewish heritage,

Laserstein lost her father at the age of just four years old. The death caused

the family to relocate into the home of the artist's maternal grandmother. Here

Laserstein's mother was known to paint ceramics and it can be presumed the

young Lotte was influenced by such artistic endeavours.

After

the family moved again in later years to Berlin, Laserstein began her adult

education in such areas as the history of art and philosophy, while also taking

lessons in painting. Her entrance into the city's College of Fine Arts during

1921 was a bold move for the young artist in the first years of the school allowing

entrance to female students. Her later completion of studies at the United

State School of Liberal and Applied Art enabled Laserstein an excellent

foundation for a career in art. The economic woes of the country in an era of

high inflation, however, took a toll on the family's finances and the young

artist was forced to work in such areas as industrial design.

Nevertheless,

Laserstein's promise in her chosen field of fine art was soon recognised by the

school, who viewed her work as amongst the best at the academy and she was

honoured by the Prussian Ministry of Science, Art and Education. Opening her

own art studio in 1927 while supporting herself by giving painting lessons, the

artist soon began creating her work in earnest. It was here, in the following

year, that Laserstein created her self-portrait with the addition of her feline

companion.

Laserstein

began to be included in many exhibitions, and her work became more widely

acknowledged as a result. Her prominent role within the Association of Berlin

Women Artists further aided her career. The painter's art was centred on

figurative reflections and portraiture in an age of post-expressionism, amidst

the growing popularity of a movement known as New Objectivism. The artistic

focus was being removed from the emotive outpourings of the previously favoured

expressionist painters and had become fixed on an unsentimental realism.

The

realistic work Laserstein produced during the late 1920s and early 1930s, often

featuring her favoured female models, certainly caught the mood of the age.

This era known as the Weimar Republic, encompassed a German renaissance in

cultural terms despite the economic and political turmoil, as the Berlin bars

bustled with artists and intellectuals within a flourishing bohemian scene.

Laserstein's

portraits reflected not only the lives surrounding her but also the mood of the

era. The painting Woman in a Café, a commission featuring the wife of a

well-known lawyer, presents the subject as a fashionably attired woman of the

age. The seated figure is featured alone with her cocktail, indicative of the

growing independent spirit of women and is posed confidently as she leans

forward to engage with the world she inhabits.

Another

of Laserstein's paintings, The Yellow Parasol (1935), is reflective of a looser

painting style for the artist and presents a young woman holding the object of

the title. While a common theme in Western art since the nineteenth century,

Laserstein added a twist to the familiar formula which avoids the contrived

depictions of femininity common in the work of artists such as Renoir.

Here

Laserstein presents her female subject as rather androgynously dressed, thus

countering the cliches of the theme. This was an age of daring exploration

after all, in which French artist Claude Cahun was toying with ideas of gender

and German-born actress Marlene Dietrich was kissing women on screen dressed in

a tuxedo. The model who posed for Laserstein's painting was known as Traute Rose,

a close friend of the artist who featured in many of her artworks and played a

significant role in the painter's life.

Despite

her increasing achievements with each new show and painting, Laserstein's

artistic career was soon to be interrupted. The rise of Nazi anti-Semitism

created a toxic atmosphere in which artists of Jewish heritage, like

Laserstein, were excluded from exhibiting. Unable to purchase art materials

easily and discharged from her role in art associations, the painter was forced

to develop a plan of escape. In order to leave her homeland, emigrate to Sweden

and gain citizenship, Laserstein married a Swedish man. However, she did not

cohabit with her new husband and set up a new life independently in Stockholm.

Her

efforts to save her mother, who remained in Germany, tragically failed and Meta

Laserstein died at the hands of Hitler's regime in Ravensbrück concentration

camp. The painter's loyal friend Traute, however, did manage to smuggle

Laserstein's artworks out of Germany, avoiding their theft or destruction under

Nazi rule. Living out her life in the Swedish capital, here Laserstein joined

the Swedish Academy of Arts and continued to work particularly in the field of

portraiture.

Understanding

Laserstein's view of herself and her work is enabled by revisiting her Self

Portrait with a Cat to decipher the codes instilled within oil on canvas. The

significance of the setting is particularly relevant. The artist's studio,

communicated by the centrality of the painter's tools in the background,

connects the figure to her work and creativity. Meanwhile, the easel, canvas

and hovering paintbrush in hand all highlight the act of painting as Laserstein

flaunts her professional abilities to the viewer. The subject is reflected in

suitable attire for the job, reflective of a practical approach to her work

which purposely ignores gendered conventions on female appearance. In addition,

the subject's hair is short, and she wears no make-up, or indeed, any sign of

expected feminine costume. While enjoying the soft textures of the cotton

overall and feline fur, the painter presents herself as particularly rigid and

her gaze is strong, while her slightly raised eyebrow seems to question the

viewer's assumptions.

Undoubtedly

painted while looking into a mirror, the painter conveys an assured

self-reflection buoyed by her burgeoning success. Also, by utilising a pose

reminiscent of the self-aggrandising statements of male painters throughout

history, Laserstein makes a carefully considered declaration of her own.

As is

the case for so many women in the arts, Laserstein's work generally went into

relative post-war obscurity and was only rediscovered in the last years of her

life. An exhibition of her work was held in the late 1980s which showcased many

of her paintings to a new generation. This included work featuring her notable

male subjects also, such as Nobel Prize-winning biochemist Sir Ernst Chain in a

1945 portrait conveyed in Laserstein's typical realist style. The exhibition

was attended by both the artist and her ever-present muse Traute, who appeared

in many intimate artworks by the artist.

Laserstein

died in 1993 as her paintings were finally receiving the international

recognition they deserved. Her legacy, in turn, is one of presenting the world

with a beguiling body of work which encompasses an obvious understanding of her

subjects, perhaps no more so than in the portrait with a fearless female gaze.

Lotte

Laserstein: the German realist who challenged expectations. By P.L. Henderson.

Art UK , February 15, 2021.

Die lange

vergessene Malerin Lotte Laserstein bekommt auch in ihrer ehemaligen

Heimatstadt einen Erinnerungsort. An ihrem Wohnhaus im Bayerischen Viertel in

Berlin hängt nun eine Gedenktafel für die Kunst-Pionierin der Weimarer Republik

In Berlin

erinnert jetzt eine Gedenktafel an die deutsch-schwedische Malerin Lotte

Laserstein (1898-1993), die für viele Menschen eine der großen Kunst-Wiederentdeckungen

der vergangenen Jahre ist. Die Tafel wurde in dieser Woche an ihrem ehemaligen

Wohnhaus in der Jenaer Straße 3 im Stadtteil Wilmersdorf angebracht, wie die

Senatsverwaltung für Kultur mitteilte. Eine feierliche Enthüllung gab es wegen

der Corona-Pandemie nicht.

Laserstein-Ausstellungen

waren kürzlich in der Berlinischen Galerie und im Städel Museum in

Frankfurt/Main zu sehen. Die Malerin gilt heute als eine der wichtigsten

Künstlerinnen der Weimarer Republik. Sie war eine der ersten Frauen, die in den

20er-Jahren an der Kunstakademie in Berlin studierte und 1937 vor den

Nationalsozialisten nach Schweden floh, wo sie eine Malschule gründete. Lotte

Laserstein war zu Lebzeiten durchaus bekannt und erfolgreich, vor allem mit

ihren sinnlichen Darstellungen von selbstbewussten Frauen. Erst mit den

Ausstellungen der vergangenen Jahre wurde jedoch ihre Rolle in der

Kunstgeschichte angemessen gewürdigt und ihr Werk einem größeren Publikum

bekannt. Inzwischen befinden sich zwei wichtige Werke in Sammlungen ihrer

ehemaligen Heimatstadt Berlin. Die Berlinische Galerie kaufte 2019 das Porträt

"Dame mit roter Baskenmütze" von ca. 1931, das monumentale Gemälde

"Abend über Potsdam" gehört der Neuen Nationalgalerie.

Gedenktafel

für Lotte Laserstein, Späte Ehre.

Monopol Magazin, June 25, 2020.

In 1929,

the German daily Berliner Tageblatt featured an art review that alerted

readers: “Lotte Laserstein – a name we need to know.” The works of Laserstein,

then 31 years old, were among those featured at the show under review. “The

artist is one of the best among the young generation of painters. We will have

cause to continue watching her shining ascent,” the newspaper promised.

In the

next few years, Laserstein fulfilled some of those expectations. Her paintings

were displayed at some 20 exhibitions in the German capital and she also

received a number of awards – but due to her Jewish roots on her father’s side,

her promising career was cut short with the rise of the Nazi regime in 1933.

After

her work was barred from being shown, Laserstein fled to Sweden where she

continued to paint, although she had difficulty replicating her budding career

as an artist there. She died in Kalmar, Sweden in 1993. It was only in the

latter years of her life that there was a revived interest in the work of the

woman who had showed such promise in the waning years of Germany’s Weimar

Republic.

“Face to

Face,” now on at the Berlinsche Galerie museum of modern art through August 12,

is an impressive, comprehensive exhibition of Laserstein’s paintings, curated

by Annelie Lütgens. It brings the artist’s work back to the city where her

career first blossomed – a city whose residents during that era feature in many

of her paintings.

Acclaimed

by the German media, “Face to Face” challenges viewers because it’s difficult

to define Laserstein’s work as belonging to any discrete aesthetic category.

The paintings on show are from the interwar period, when the artistic landscape

in Germany was characterized by a multiplicity of avant-garde styles and

trends. Laserstein excelled particularly in her warm and empathetic portraits,

many of which featured modern, liberated women, but even when addressing

innovative ideas in her paintings, she maintained a meticulous realistic style

that was unusual in her day.

The prime

example of this is her best-known painting, a large work from 1930 entitled

“Evening Over Potsdam,” portraying five people deep in thought, sitting around

with a table on a rooftop terrace, with a dog. In the background is the city

skyline at twilight, overshadowed by dark clouds. Despite its realistic style –

and the fact that it is somewhat reminiscent of Da Vinci’s “Last Supper” and

Johannes Vermeer’s “The Milkmaid” – the painting conveys an aura of unease and

sorrow, which appears to be an accurate reflection of the era in which it was

created, in the late 1920s, when economic and political crises shook Germany

and ultimately led to the rise of Nazism.

“Evening

Over Potsdam” and a good number of other paintings by Laserstein are proof that

the artistic spectrum during the Weimar years was broader than generally

thought, says German art historian Dr. Anna-Carola Krausse. About 15 years ago

Krausse produced a groundbreaking, comprehensive study of Laserstein’s work and

curated an exhibit of her work that marked the beginning of renewed interest in

the artist, in Germany.

Laserstein

combined the 19th-century academic style in which she was trained with

contemporary subjects, says Krausee, thereby allowing us to expand the

significance of the concept of artistic modernism. And although her work was

undoubtedly modern, it also shows how figurative and not just abstract painting

can capture the spirit of an era.

The

Berlinische Galerie show features about 60 of Laserstein’s works, most from the

early years of her career in Berlin, although some are from her time in exile

in Sweden. Also on display are the palette she used, as well as photographs and

documents that offer insight into her life.

Discovering

Rose

Lotte

Laserstein was born in a small town in East Prussia in 1898; her mother who was

a pianist and a father who was a pharmacist and died when she was very young.

She moved with her mother and sister to Danzig (now the Polish city of Gdansk).

As a girl, she studied painting with her aunt, who was also an artist.

The

family moved to Berlin before World War I, and thereafter Laserstein studied

philosophy and art history at the city’s Friedrich Wilhelm University. She was

then accepted at the Berlin Art Academy, which had just opened its doors to

women a few years beforehand. One of her primary instructors there was the

German-Jewish painter Erich Wolfsfeld.

In 1925,

by chance, Laserstein met a salesclerk named Traute Rose, whom she asked to be

a model for her paintings. The two became close and Rose, who went on to be an

actress and singer, features in many of the artist’s works. On more than one

occasion, Rose appeared next to the artist in them, and was considered to be an

equal partner in the composition – as opposed to the usual artist-model

hierarchical perception.

As with

other women whom Laserstein painted, Rose fit the image of the “new woman” of

the Weimar period, a time when women were gaining increasing independence.

Along with the right to vote, they were taking jobs that had been previously

seen as men’s work and in some instances, even adopted a male or androgynous

appearance.

During a

tour of the current show, art historian Krausse draws particular attention to

Laserstein’s portraits of women, including “Tennis Player” (1929), depicting a

sport that was becoming popular at the time in Germany; “Girl Lying on Blue”

(1931), which was selected as the exhibition poster; and “Self-Portrait with a

Cat” (1928), in which the artist sought to demonstrate her professional

capabilities, toying with the tradition of self-portraiture, according to

Krausse.

In the

painting the cat represents femininity and the artist is dressed like a man and

has a man’s haircut. The viewer will note that the canvas near her in the

painting is blank: It’s the painting that she is about to create, while still

sitting and peering into the mirror. Here, as with other works, Laserstein was

trying to understand perspective, allowing us to see together with her rather

than seeing through her, says Krausse.

Not a

‘party girl’

Another

major work from Laserstein’s early years is “Russian Girl with Compact” (1928),

which depicts a young woman from Russian émigré circles in Berlin – which

didn’t keep Laserstein from winning a prize in a competition of portraits of

German women, sponsored by a cosmetics firm. The way in which the artists

presented the émigrée as a young, up-to-date urban woman who is meticulous

about her appearance, suited the growing discourse at the time about the

importance of fashion and grooming in exhibitionist Western society.

Krausse

stresses that, “In Laserstein’s portraits of women, as opposed to portraits

created by male artists of the time, the model is not perceived as an object,

but rather as a subject. She presents them as women with natural

self-confidence, without provocations or eroticism, and also without a

perception of ‘sweet’ femininity, as can be found in other female painters of

the time. There is no difference in the way she paints men and women.”

An

example of this is one of her important paintings, “In the Tavern” (1927),

which portrays two women, each sitting alone in a café. The painting, which is

not included in the present exhibition, was originally acquired by the Berlin

municipality and later confiscated by the Nazis, who described it as

“degenerate art.”

That

work is also exceptional among Laserstein’s oeuvre because it focuses on the

new and vibrant urban culture of the early 20th century – a subject that

preoccupied many artists during her time but for the most part did not arouse

her curiosity. Krausse explains that Laserstein was not involved in the

Bohemian cultural scene in Weimar Berlin.

“She

wasn’t a ‘party girl’ and didn’t spend time with the great artists of the

period at the Romanisches Café or other places in the city where they would

go,” says the historian. “Moreover, avant-garde was not her natural milieu, and

when she began her independent career in the late 1920s, Expressionism, Dada

and Surrealism were in any case no longer in vogue. She worked parallel to the

artists of the New Objectivity movement, including Max Beckmann, Otto Dix,

George Grosz and Christian Schad, and she really resembles some of them in her

post-Expressionist style and her return to naturalistic painting. But as

opposed to them, her work does not contain scathing political and social

criticism.”

During

her most productive years Laserstein received a prize from the Prussian

Ministry of Art, joined the association of women artists in Berlin and had a

solo exhibition at the highly regarded gallery of Berlin art dealer Fritz

Gurlitt. But shortly after Hitler’s government took over, she was banned from

participating in shows and her studio was closed.

Laserstein

earned a living as an art teacher at a Jewish school in Berlin and in 1937,

after being invited to mount an exhibition in Stockholm, took advantage of the

opportunity in order to flee, taking a selection of her paintings with her. In

Sweden she made a living mainly from selling work on consignment. She tried

unsuccessfully to help relatives who remained behind in Germany: Her sister

survived in hiding in Berlin during the Holocaust, but their mother was

arrested and died in the Ravensbruck concentration camp.

After

the war Laserstein visited Germany and renewed her relationship with her friend

Rosa, but she never returned to live in the country. She lived in the Swedish

city of Kalmar and although she continued to paint and exhibit from time to

time, she found it difficult to revive her reputation – both because of her

style, which didn’t suit the new trends in European art, and because of her

distance from the centers of the European art scene.

Before

Laserstein died in 1993, however, she did witness the rediscovery of her work,

which began in 1987 with an exhibition in London. It continued with greater

momentum after her death and since the beginning of the millennium, her

paintings have aroused great curiosity among curators, art scholars and

collectors alike. Their prices have also been rising steadily in the past

decade: “In the Tavern” was sold at public auction for 110,000 euros, and

“Evening over Potsdam” was acquired by the New National Gallery in Berlin for

350,000 pounds sterling (about $435,800).

Among

art-lovers in Israel Laserstein is still not very well known – although

“Evening Over Potsdam” was one of the prominent works in the German art

exhibition “Twilight Over Berlin,” held about four years ago at the Israel

Museum in Jerusalem. The artist and the painting were also represented in a

charming literary form in the 2018 Hebrew novel “The Modern Dance” by Michal

Sapir, where they come to life in a story inspired by the writings of Jewish

philosopher Walter Benjamin, which takes place in Berlin during the twilight of

the Weimar Republic.

“We were

guests with a group of friends at an evening meal in the home of painter Lotte

… in Potsdam,” writes Sapir, in the voice of the main protagonist, who is

looking at the city spread out before his eyes beneath a cloudy and murky sky.

“Dora was wearing her sleeveless yellow summer dress. The air breathed heavily

in the oppressive heat of late summer. On the table leftover bread from the

meal and a few pale apples and pears were scattered. I stood there on the

balcony permeated with a feeling of endless exile …

“Lotte

poured milk into the coffee cups. Erwin Kraft [another character] still had a

half-full glass of beer in his hand … I returned to the table and looked at my

friends who were sitting immersed in a soft twilight melancholy, averting their

pensive glances from one another. I imagined them, each one of them, replacing

their facial expressions with the numbers on the face of an alarm clock, which

rang for 60 seconds every minute.”

Work of

a Nazi-banished Artist Is Back in Focus in Berlin. By Avner Shapira. Haaretz, July

25, 2019.

‘Face to

Face’ is an apt title for this comprehensive survey of the work of Lotte

Laserstein (1889–1993). Throughout her life, Laserstein was preoccupied with

the enigma and confrontation of the returned stare, her own emerging as the

most constant and profound of all. It is the portraits, specifically the

self-portraits in which Laserstein’s dark eyes look back at us under hooded

lids, with an almost haughty upward tilt of her top lip, that make an indelible

impression. A ‘face-to-face’ suggests a deeper level of communication and, with

this on offer, we have an obligation to return the gaze squarely, with eyes and

mind open.

The

vivid portraits of the new women and modern men of the Weimar Era for which she

is celebrated are carefully complemented in this show (which has travelled from

the Städel Museum) with landscapes and later works made after Laserstein

emigrated to Sweden in 1937. If these works lack the edge of those from the

Berlin years, they reflect how, in enduring the mental schism of forced exile,

her relationship to her talent became complicated. She took on commissions to

earn a living, but in 1946 felt ‘wretched that after nine years in Sweden one

is no further on than at the beginning’. Gothenburg Harbour (1943), a nocturne

drawing inspiration from Old Masters as much as lens-based innovations of the

age, enriches our understanding of what Laserstein could do with paint, but the

later works also question the idea that suffering begets ‘great art’.

Classified ‘three quarters Jewish’ under the Nazi dictatorship, Laserstein had

been banned from participating in German cultural life after 1933. In 1943, she

learned that her mother had been murdered at Ravensbrück concentration camp.

Laserstein’s

bravura skill as a draughtswoman reaches its peak in her masterpiece Evening

Over Potsdam (1930). Here, the looming political nightmare seems to descend

over a group of weary moderns engaged in a secular version of The Last Supper.

This skill was, perhaps, a sort of albatross in the era of the ‘New

Objectivity’, with contemporaries such as Christian Schad and Jeanne Mammen

pursuing a more obviously avant-garde agenda. But how might she have warped her

line to greater effect? What did it mean to possess such pure illustrative

technique, when everything about your identity could be deemed ‘warped’?

The

exhibition texts avoid comment on Laserstein’s sexuality, erring towards the

idea that ‘if anything, it is painting itself that comes across as the erotic

act for Laserstein’. As a queer viewer, it is not that you demand an absolute

position on the artist’s sexuality, rather that the conversation shouldn’t

always lean towards a heteronormative viewpoint; one that regularly assumes the

potential sexual relationship between a male artist and his muse, but ignores

or neutralises what is on display here. Laserstein’s portraits of her ‘friend’

Traute Rose are laced with same-sex intimacy. It is widely agreed that

Laserstein’s great power is her ability to communicate psychological states

between characters or, indeed, the characters and ourselves. It therefore seems

odd, blind even, to turn away from Laserstein’s sexuality.

In I and

my Model (1929/30), the artist works at her easel, her face turned to confront

the viewer, her eyebrows arched knowingly. Traute, not classically nude, but in

a domestic state of undress, observes close behind, her hand on Laserstein’s

shoulder where a patch of light beneath electrifies the gesture. It is a

radical take on the gendered power-play of the artist and model, feminist in

its depiction of care and interdependence, while glinting with delight and

provocation. Its erotic charge is picked up in a series of quick, tender

sketches of Traute sleeping naked in bed, executed on pages from a small

sketchpad that might have been kept by the bedside and reached for upon waking.

In the At the Mirror (1930/31), the naked Traute grapples with a mirror. Her

back is to the viewer, so that her reflected stare is the only clearly visible

face in a composition that hints at The Three Graces. Traute meets her own

determined, sensual expression as Laserstein stands braced in front of her

easel in a dingy workman’s coat, energetically squeezing paint on to her

palette. Traute, the mirror, and the edge of Laserstein’s canvas as it slices

back into the picture plane, are luminous elements in the painting, framing

Laserstein, as she so often depicted herself, at work.

Is it

time to take Lotte Laserstein at face value? By Phoebe Blatton. Apollo Magazine, June 20, 2019.

Emily

May speaks to the curator of Face to Face, a retrospective on the work of the

portrait painter Lotte Laserstein.

“The

Golden Twenties” hold a special allure for many people. During this time cities

all around the world were overcome with raucous parties and artistic

innovation, but none as much as Berlin. Funded by American loans, and under the

leadership of the newly formed democratic Weimar Republic, the post-war German

capital enjoyed a new era of decadent nightlife and nurtured the beginning of a

plethora of decade-defining artistic movements, all whilst living in the shadow

of political turmoil and the horrors that were yet to come. 100 years since the

Weimar Republic was formed, and with the centenary of the beginning of this

culturally rich decade a year away, it is unsurprising that there are a

plethora of exhibitions and events paying homage to the artists who made the

roaring twenties so special.

One such

exhibition is Face to Face, an upcoming retrospective at the Berlinische

Gallery (produced in collaboration with the Städel Museum, Frankfurt) which

explores the work of the portrait painter Lotte Laserstein. Opening on 5th

April and running through to 8th December 2019, Face to Face will shine a light

on a largely forgotten Weimar artist. We spoke to the exhibition’s curator,

Annelie Lütgens ahead of the opening to find out more about why Laserstein, and

female painters and thinkers in general, are enjoying new-found attention in

2019.

“I

[first] became interested in the art of the Weimar Republic during my studies

in the late 1970s, when contemporary art turned [towards] realism and a

critical view towards… society” says Lütgens, who is the head of the department

of prints and drawings at the Berlinische Gallery. “Out of this I discovered

women artists of the twenties and started to make research” she continues,

saying that she is not only inspired by painters and drafts people, but also

women writers of the period such as Irmgard Keun, Djuna Barnes, and Annemarie

Schwarzenbach. “All these people tried out, suffered, and finally made their

own independent lives as women and artists” says Lütgens. “They are… models still for today.”

The

paintings of Lotte Laserstein capture the emergence of such strong female

personalities. Whilst she depicted subjects from all areas of society, she is

particularly renowned for her portrayal of the newly liberated women of the

era. “The New Woman, as she was known in the 1920s, wore practical clothes and

cut her hair short” Lütgens describes. “Lotte Laserstein repeatedly returns to

this contemporary type [in her painting] and she also embodied it herself” she

continues. “In her self-portraits, Lotte Laserstein reflects visually on her identity

as an artist and as a woman. Like many artists, she uses the genre to convey

how she sees and wishes to be seen.”

Laserstein’s

status as a “New Woman” herself give a different feel to her work in comparison

to that of contemporary portrait painters such as George Grosz and Otto Dix,

the latter of whom also depicted famous women from Weimar society, such as the

cabaret dancer Anita Berber and the journalist Sylvia von Harden. Lütgens cites

Laserstein’s double portraits of herself and her sitter Traute Rose as perfect

examples of how the artist’s female gaze sets her apart from her male

contemporaries. “These intimate double portraits challenge the conventional

motif of male artist and muse, replacing the traditional hierarchy with

sympathetic collaboration,” she says, stating that “Laserstein depicts the

painter and sitter as equal partners.”

Despite

the innovative nature of Laserstein’s work, her name is less familiar to the

public than those of Dix and Grosz, who are consistently prominent in

exhibitions about the period. Take the recent Aftermath: Art and War in the

Wake of World War One display at London’s Tate Modern as an example, which

focused largely on male artists. “The rediscovering of women from the Weimar

period started later [than that of] painters like Dix and Grosz” Lügtens

laments, yet she does admit that even “they too were forgotten in the first

decades after World War Two when abstract art was the favorite style.” Although

there has been a rise in the number of retrospectives in the past few years to

shine light on the work of forgotten female Weimar artists, Lütgens asserts

that “women painters should be part of exhibitions as a matter of cause.”

One such

recent female-focused retrospective was Jeanne Mammen: The Observer, which was

also curated by Lütgens, and came to the Berlinische almost exactly one year

before Face to Face. Whilst one might think that Mammen and Laserstein’s works

are very similar, due to their joint focus on the archetype of “the New Woman”

and the fact that they pursued “an independent artistic life without being part

of a married couple or having children”, Lütgens informs us that there are in

fact many points of contrast between their artistic styles. “Jeanne Mammen

trained as an artist in France and Belgium,” say Lütgens. “She had another

background as – you could say – a European big city girl, and she had a

left-wing political opinion. She was more of a draftsperson than a pure

painter, even in her paintings of the Twenties. Mammen’s style is based on

French art, like [that of] Toulouse Lautrec or Steinlen” she continues.

Conversely, “Laserstein’s painting is based on German art of the late 19th

Century, which is more traditional” Lütgens explains, citing artists Max

Liebermann, Wilhelm Leibl and Karl Schuch as influences on her work. But

despite these conservative beginnings, Laserstein’s approach did transform over

time. “[Her] way of painting became more open in the 1930s. She developed a

sensual painterly style which could be compared for example to the French

painter Emile Bonnard.”

The

development of Laserstein’s style could be seen as a result of her to her move to

Stockholm from Berlin in 1937, where she sought refuge from the Nazi party who

had forbidden her to participate in public cultural life in Germany due to her

Jewish heritage. This change of artistic base also provides another point of

comparison between Laserstein and Mammen. “While Mammen did not emigrate and

developed her art of resistance in Berlin, Laserstein had to leave her

boundaries, and because of that… struggled for her artistic identity” asserts

Lütgens. Upon first moving to Sweden, “her portraits of elegant women… seem to

pick up where they left off in Berlin. But as time passed, she found the

pressure to earn a living from commissioned portraits wearisome and not very

inspiring” the exhibition curator informs us. “She seized every opportunity to

tackle new artistic challenges including murals for private and public

buildings, [but] her struggle to cater for prevailing tastes in art without

giving rein to her true talents plunged her into deep resignation”.

The Face

to Face exhibition in Berlin will feature artwork from both the artists’ Berlin

and Swedish periods to allow comparison, and perhaps to make people wonder how

the painter’s style would have developed if her unfortunate position as a

person of Jewish heritage in 1930s Berlin had not diverted her course. Whilst

Lütgens states that she cannot imagine how Laserstein’s artistic career would

have developed if she had been able to stay in Berlin, she does posit that “her

traditional style of painting could have been favorable in the Nazi era, but

her images of women would definitely not.”

It’s a

feeling that can’t be more removed from today when images of strong women from

history are celebrated in the market. Take the rediscovery of Renaissance

artist Artemisia Gentileschi for example, whose paintings of strong, powerful

women attracted waves of market interest, so much so that her Lucretia sold for

more than double its high estimate last October, realizing €1.88 million ($2

million). Lütgens seems confident that Face to Face will receive a positive

reception. “I hope people will take away moments of happy awareness having been

introduced to one of the most gifted artists of the Weimar era” she states. “I

am sure the audience will love Lotte Laserstein’s work.”

The Exhibition

Rediscovering One of the Weimar Era's 'Most Gifted Artists'. By Emily May.

Mutual Art, March 25, 2019.

Lotte

Laserstein was a rising star of Weimar Berlin, forced to leave her country and

abandon her artistic aspirations, but with this exhibition of highlights from

her peak, there is hope that her name may yet not be forgotten

Face to

face. An appropriate title for an exhibition so largely comprised of portraits

– among them a large proportion of self-portraits. For, surrounded by these

canvases of Lotte Laserstein (1898-1993), one feels beset by myriad pairs of

eyes. She is usually categorised as an artist of Neue Sachlichkeit (New

Objectivity), alongside her male contemporaries Otto Dix, George Grosz and

Christian Schad, but her style is really quite different from theirs – devoid

of political satire and containing far more empathy, intimacy, and, dare I say

it at the risk of sounding disingenuous, femininity.

Laserstein

grew up in a very female environment, with her mother, her sister, Käte, and

her aunt and grandmother, following the death of her father in 1902.

Fortunately, there was enough family money for both daughters to study and

Laserstein was one of the first generation of women accepted into the Berlin

Art Academy, in 1921 – two large charcoal drawings of male nudes evidence that

she also attended life classes while there. Bear in mind that she was painting

at the same time as, for example, the artists of the expressionist group, Die

Brücke, and her style might seem a little old fashioned and venerating of art

history – “more academy than avant garde”, as Kolja Reichert wrote in the

Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung (23 September 2018). One hypothesis put

forward by the exhibition texts is that, belonging to this first generation of

educated female artists, she lacked the rebellious streak of many of her male

contemporaries, wishing instead to prove her technical ability. Vermeer, for

example, was one artist she openly declared to be a great influence on her, and

aspects of the Dutch master’s style can be detected, especially, perhaps, in

her choice of palette.

Nevertheless,

Laserstein was not prosaic in her choice of subject, frequently depicting the

“new woman”, androgynous and with short-cropped hair. Her close friend and

favourite muse, Gertrud Rose, known as Traute, who modelled for 90% of

Laserstein’s nudes, embodies this “type”. There has been repeated speculation

over a lesbian relationship between the two women, but this seems, on the

whole, to be unfounded – as well as somewhat irrelevant and an example of our

contemporary classifications muddying those of the past. Not only was Traute

happily married, but Laserstein’s sister, Käte, was in an openly lesbian

relationship, so it seems unlikely that Laserstein should have remained in the

closet, were this the case.

As well

as paintings of Traute, there are, as mentioned, a great number of

self-portraits on display, as well as paintings in which Laserstein appears in

the background, frequently wearing her painting shirt, as a kind of attribute.

For example, In meinem Atelier (In my Studio) (1928) depicts Traute in a

classical reclining Venus pose, set against the snowy rooftops of Wilmersdorf,

Berlin. Between the foreground and background, the artist is present, standing

– and working – at her easel. This is, in fact, an impossible composition,

since, from the position in which Laserstein is standing, Traute would have had

to appear in reverse. Additionally, while the painting itself is oil on board,

in the picture, Laserstein is painting on canvas. Still, who is to deny a

little artistic licence?

This

mirroring is, in fact, something Laserstein plays with in a number of her

works, including also a later self-portrait in which she stands – somewhat

poignantly, as will soon become clear – before her masterpiece Abend über

Potsdam (Evening over Potsdam) (1930). In this example with Venus, however, the

artist’s presence acts further to prevent the viewer from laying claim in his

or her mind to the passive female (albeit androgynous) nude – since she is

already “possessed”. By “possessed”, however, I don’t mean to suggest any sense

of hierarchy or object-subject relationship – there is far more a sense of

equality between the artist and her model, as also captured in Zwei Mädchen

(Two Girls) (1927), which, with its close crop and studious but young and

carefree poses, is my favourite work in the show.

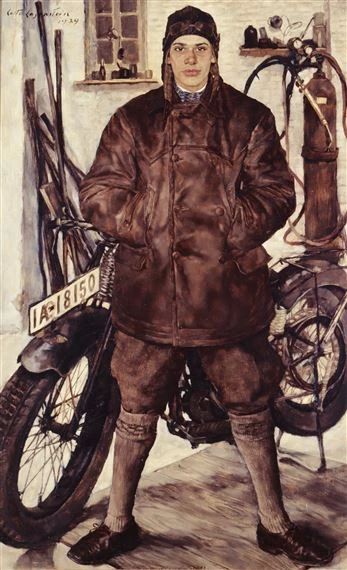

Laserstein

worked mainly with four basic sets of green-brown colours, and painted alla

prima, largely with just one layer. Nevertheless, she was able to successfully

create a convincing illusion of different materials, including, for example,

leather and metal in Der Motorradfahrer (The Motorcyclist) (1929).

The

hypnotic Russisches Mädchen mit Puderdose (Russian Girl with Compact) (1928),

with its luxuriously rich crimson red, was one of the 25 finalists in a

competition run by the cosmetics company Elida to find the most beautiful

portrait of a woman in 1928. The model was the daughter of Laserstein’s Russian

lodgers. In fact, she found many models among Russian exiles, following the

1917 revolution. This work and the later Junge mit Kasper-Puppe (Wolfgang

Karger) (Boy with Kasper Puppet (Wolfgang Karger)) (1933) were both recently

acquired by the Städel Museum, and it was around these that this long overdue

exhibition was conceived.

This is

the first time in Germany – outside Berlin – that Laserstein has been

recognised with a proper retrospective. This comes as little surprise, however,

given that she emigrated to Sweden in 1937, having been forbidden to work or

exhibit in her own country, following the introduction of the Nuremberg race

laws in 1935. Although a baptised Protestant, Laserstein had three Jewish

grandparents, and was accordingly declared “three-quarter Jew” by the

authorities when she turned to them for help. Cleverly – and luckily –

Laserstein organised an exhibition in Stockholm, comprising much of her work,

and, travelling there to “take it down”, simply stayed. Six months later, she

married a Swede, so as to obtain citizenship, and she never returned to Berlin.

This

exhibition comprises 40 paintings and drawings, primarily from the Weimar

period of the late-20s and early 30s. Laserstein’s life’s work as a whole

comprises about 10,000 pieces, but many of these – with examples being the

somewhat kitsch portraits of children on white backgrounds on display in the

final space – were produced for clients in Sweden so as to earn a living, and

weren’t what she would have wanted to be producing, either in terms of style or

subject matter. “I can’t develop any further artistically,” she declared during

this period. Accordingly – and, I believe, rightly – the curators have chosen

to largely overlook these later works, excepting a few self-portraits, painted

purely for herself, and thus enabling some element of continued

experimentation.

Laserstein’s

key work is generally considered to be Abend über Potsdam (Evening over

Potsdam) (1930), which has been likened by one of the curators, Elena Schroll,

to a depiction of the Last Supper. Certainly there is a sense of impending

depression (this was painted, quite literally, on the eve of the Depression),

and the excitement of the “roaring 20s” has been replaced by an overt sense of

melancholy. The five friends (painted after real-life friends of the artist,

with Traute on the left-hand side – although the woman on the right, less of a

patient model, actually has the legs of Traute beneath her own head and torso,

and the dog, the least patient model of them all, was largely painted from a

fur Laserstein had in her studio) seem no longer to know what to say to one

another.

The logistics

of producing the work were impressive, not just in terms of improvisation and

problem-solving when it came to the models, but the one-metre-high by

two-metres-wide canvas was transported by S-Bahn (overground train) from Berlin

to a friend’s house with a roof terrace in Potsdam, and then back again to

Berlin to be finished in Laserstein’s studio. Deservedly, that same year, Das

Berliner Tageblatt declared: “Lotte Laserstein – this is a name to watch. The

artist is one of the very best of the young generation of painters, her

glittering path to success will be one to follow!”1 Schroll similarly describes

Laserstein as a “rising star”, but she was sadly a rising star who had to flee

her homeland and abandon her achievements long before reaching her zenith. With

this presentation of highlights from her peak, there is hope that she might yet

not be forgotten.

Lotte

Laserstein : Face to Face. By Anna McNay. Studio International, November 19,

2018.

No comments:

Post a Comment