At the

moment, fascism has to be the most sloppily used term in the American political

vocabulary. If you think fascists are buffoonish, racist, misogynist despots,

the people who support them are deplorable, and a political leader who incites

paramilitary forces against protestors is not much different from Mussolini

unleashing his black-shirted thugs against unarmed workers, you may be tempted

to call the current president of the U.S. a fascist. But then the president,

too, has taken to labelling his enemies fascists. And who wants to argue about

semantics in that company?

Make no

mistake: Understanding what fascism meant in its time, 1920 to 1945, is

absolutely crucial to understanding the gravity of our own current national

political crisis—as well as to summoning up the huge political creativity we

will need to address it. But we won’t get close to that understanding if we

keep confusing fascism, the historical phenomenon, with fascism, the political

label.

If you

grew up as I did, in the United States after the Second World War, everyone

seemed to be an anti-fascist, at least at first. America had fought the good

fight, and triumphed. I ached at my father’s war stories about the misery of

the newly liberated Italians, studied army snapshots of him in front of a mound

of corpses at Dachau, and suffered nightmares at learning what the Nazis and

the Fascists did to the Jews.

But the

picture grew complicated. From my Jewish American mother, a New Dealer and

later a communist fellow traveler, I learned that McCarthyism was the form

fascism took in America. After my study abroad in Italy during the 1960s, where

I had joined student and worker demonstrations against the country’s

still-vivid authoritarian streak, I came home rhetorically armed to denounce

fascists. America seemed riddled with them—starting with those “fascist pigs”

in the Princeton, New Jersey, police force who hauled the Black kids (and my

little brothers) into custody for Halloween pranks and held them indefinitely,

as if habeas corpus didn’t apply to juveniles. My Smith College dorm mother was

a fascist for enforcing fascistic-patriarchal rules in loco parentis, as were a

couple of professors who argued that fascism and communism were opposite sides

of the same coin. The ranks of the fascists included LBJ for Vietnam, Nixon and

Kissinger for many reasons, and even my father (who also supported the Vietnam

war) for his haywire libertarian politics.

Calling

people “fascists” has been as American as apple pie for as long as I can

remember. But, after becoming a scholar of fascism, I came to see the

phenomenon of fascist labeling very differently.

This is

especially true now, 20 years into the 21st century, heading up to the 2022

centenary of Mussolini’s March on Rome.

It’s

been 75 years since the coalition of armies—spearheaded by the U.S., the Soviet

Union, and Great Britain—crushed the Axis belligerents, Germany, Italy, and

Japan. And it’s been 30 years since 1990, when the relatively stable Cold War

world order, ruled by the two superpowers, broke up with the dissolution of the

Soviet bloc.

I now

see the fascist phenomenon with new context—the crumbling of the liberal norms

that were constructed to save the world from a recurrence of authoritarianism

after World War II; the social inequities and financial crises arising from

globalization; the failures of American unilateralism; and the obsolescence of

domestic and international institutions in the face of new challenges, from

climate change to the COVID-19 pandemic, that are posed to wreak even greater

global disorder.

In this

21st-century light, fascism and its horrific trajectory in the second quarter

of the 20th century look at once inexorable and global, awful and attractive,

even understandable. Fascism, its early 20th-century proponents claimed, had

all of the answers to the political, material, and existential crises of the

British-led imperialist world order in the wake of World War I: It would

mobilize the militarism generated by World War I to reorder civilian life. It

signaled a third way between capitalism and socialism by imposing harmony

between labor and capital. And fascism would establish new racial hierarchies

to defend the West against soulless American materialism, Judeo-Bolshevism, and

the inexorable advance of Asia’s “yellow masses.” It would knock the

hypocritical British Empire off its plutocratic pedestal, destroy the puppet

League of Nations, and carve out new colonial empires to let the proletarian

nations of the world get their just desserts.

It makes

sense that Italy was home to the first fascist takeover. After surviving well

enough as a second-order power through the end of the 19th century, the

country’s retrograde monarchy eschewed undertaking needed social reforms and

instead got swept up in the competition for colonies, empowering a flamboyant

young nationalist right. These activists dominated debates in the piazzas and

ultimately pushed the country to enter World War I believing it would be richly

rewarded with new lands.

But that

vision was not to be. Mobilizing at a grand scale to fight the Austrians and

Germans unhinged Italy’s political system. The country divided into

interventionist and anti-war camps. After fighting ended, the old political

class secured a few new territories out of the Versailles Peace Conference, but

not enough to satisfy the imperialist expectations of the pro-war factions. Nor

could elites deliver a substantial program of reforms that would have made war

sacrifices seem worthwhile to the ever-larger, ever-more-exasperated movements

of workers and peasants spearheaded by socialist and Catholic opposition

parties.

By 1921,

the liberal political elite calculated that if it opened its electoral

coalition to Benito Mussolini’s burgeoning fasci di combattimento movement, it

could coopt this vigorous political upstart, punish the left and Catholic

opposition, and shore up its own power.

Who

better than the brilliant, unscrupulous journalist Mussolini, a leading

socialist turned radical nationalist, to offer a new way? Lover and tutee of

brilliant cosmopolitan women, with a facile ear for big ideas and overweening

self-confidence in his political intuition, Mussolini claimed to be both a

revolutionary and a reactionary—and positioned his anti-party’s armed squads as

the only bulwark against the Reds’ advance. Avowedly opportunistic, he seized

every moment to bash the opposition, ingratiate himself with the old elites,

stymie alternative solutions, and woo the military and the police by stressing

their shared struggle to restore law and order against the Bolsheviks.

Called

by the king to form a coalition government, Mussolini embarked on a restoration

more than a revolution. He established an unshakable political majority by

outlawing opposition parties. He revived the economy through austerity

measures, outlawing non-fascist unions, and renegotiating war debts to prompt

U.S. capital to pour into Italy. He restored national prestige by swagger and bluff,

no longer a junior partner to Great Britain in the Mediterranean and East

Africa, but a freebooting statesman with the ambition to reestablish Italy’s

Roman empire.

Fascists

spoke of the state as something alive, with a moral personality of its own, and

justifiably predatory to survive in a Darwinian world. They celebrated people

as energetic animals—New Men and Women who needed hierarchy and a true leader

to harness their vigor. The males could become more virile breedstock, the

women more fertile, all for the purposes of the State.

Between

1920 and 1930, as Mussolini turned his one-time radical-populist social

movement into a giant party-militia, seized power, and transformed his

government into totalitarian dictatorship—in his words, “Everything in the

State, nothing outside the State, nothing against the State”—fascism

established itself as an international reference point for a wide array of

like-minded political entrepreneurs and collaborating movements. With the Great

Depression, Adolf Hitler’s seizure of power in Germany, and fascist Italy’s

alliance with the Third Reich, fascism would transform into a multi-pronged

global force. Militarily, Mussolini conquered Ethiopia and Hitler re-armed,

both in defiance of the League of Nations. They intervened to help General

Francisco Franco overthrow the Spanish Second Republic and formed their

anti-Bolshevik Axis with Imperial Japan.

Economically,

fascism appealed during a worldwide depression because it seemed to have found

a winning model to confront it: closed economies, big state spending, and

tightly controlled labor organizations and markets to control wages and

inflation. Revved up by rearmament spending, Germany was becoming the new

engine of Europe and the leading trade partner for most of its neighboring

nations. Germany boasted that it had no unemployment, and Italy had at least

suppressed the visibility of out-of-work citizens by recruiting them for its

ever-growing volunteer militia, sending them back to their rural home towns,

settling them in its new empire in Libya and Ethiopia, or offering them

assistance through winter help funds. In both regimes, leaders claimed, capital

and labor cooperated in the national interest.

Political

enthusiasm displayed itself in whole peoples uniformed and integrated into mass

organizations, their distinctions effaced, united in their cult of the leader.

By 1938, propagandists were speaking of the Nazi-Fascist New Order as the true

heir to European culture. It launched a counter-Hollywood in the form of UFA, the

giant German-dominated film production and distribution cartel, and financed

joint film productions with the Japanese as well as a dazzling film festival at

Venice to counter the one at Cannes.

The

Nazi-Fascist New Order championed the new sciences of demographics and race

hygienics in scientific congresses and exchanges. It fostered debates over how

to revive jurisprudence and political science by differentiating between

friends and enemies in legal codes and in international law and how to build

more totalizing welfare states by incorporating sports and healthy eating, in

addition to eugenic measures to prevent “useless” lives from detracting from

the social good. And it portrayed itself as a pioneer in geopolitics, striking

a new balance so that all of the world’s great powers would have their

so-called vital spaces or “lebensraum.” Just as the U.S. would rule Latin

America through its Monroe Doctrine, fascist geopoliticians said, Italy would

have Eur-Africa, Japan its Co-Prosperity Sphere in Asia, and Germany its

Ost-Plan for colonizing eastern Europe and Russia. On that basis, fascism had a

right to make war and for the winning regimes to re-distribute chunks of

colonial empire to the “deserving.”

It’s

scary to look at a map of the world in 1941: continental Europe conquered for

the New Order, the Nazi war machine at the gates of Moscow; Italy in the

Balkans, its armies in the field from Benghazi to British Somalia; Japan

occupying much of East Asia. The war was a true crusade, driven by its dictators’

furies, as well as old-fashioned imperialism: for the fascists, winning meant

not just territorial conquest, but population elimination including the global

eradication of the Jews, wholesale pillage, and capturing prisoners for slave

labor. The tyrants had few qualms about immolating their own peoples to salvage

their lost cause. Rather than capitulate to the Allies in June 1943, Mussolini

abandoned Italy to German military occupation and two more years of

bombardment, invasion, and civil war. Refusing to capitulate as Soviet forces

encircled Berlin, Hitler summoned his people to continue the “sacrifice” and

“struggle,” then killed himself.

Americans

may think we know this history, but we have oversimplified its complexity.

Boasting about defeating fascism, and declaring it our duty to police the world

against any recurrence, we have lost sight of the global crises of the early

20th century, born of World War I and the Great Depression, that fascism was

invented to address.

Over

time, we have become accustomed to political leaders of both parties turning

the history of fascism into a set of political hobgoblins to legitimate new

wars. Never again a Munich, where the great powers capitulated to Hitler, to

justify intervention in Vietnam. Never again the Holocaust, to justify

intervention in the Balkans and Libya. Never would we bow to an Arab Hitler, to

justify invading Iraq and overthrowing Saddam Hussein.

We also

have gotten used to Hollywood turning the U.S. encounter with Nazi-Fascism into

mawkish images of good and evil, and to facile evocations of the Holocaust

making Antisemitism practically the sole measure of what it meant to be

fascist. “Fascinating Fascism” is the term Susan Sontag, the literary critic,

once used to call out American culture’s superficiality at being beguiled by

fascism’s kitschy aesthetics and by the sadomasochistic pleasure of thinking of

fascism as chains and shackles that, once shaken off, reinvigorate the meaning

of being whole and free.

By

cultivating such a jejune view of what fascism was historically, we have

struggled to understand the highly relevant story of why it took two decades

between the world wars to develop a coalition powerful enough to fight it.

Fascism always had opponents, of course, but they—dyed-in-the-wool

conservatives, old-fashioned liberals, Catholic centrists, social democrats,

communists, and anarchists—were deeply divided. Mussolini got points from his

men when, after outlawing the opposition, he brushed off its leaders as

“anti-fascists,” meaning they had no program except to contest his.

It is no

disrespect to the hard-fought struggles of anti-fascist forces to underscore

how hard it was to win, much less sustain, electoral victories once the right

in polarized political systems aligns itself with forces identifying with

fascism. In Spain, the left-wing coalition known as the Popular Front won in

February 1936, only to be overthrown by a military coup, backed by

international fascism. In France, the May 1936 victory of the Popular Front was

reversed in short order as capital took flight for fear of a Red revolution,

the economy stalled, and the coalition dissolved.

Most

places sought to immunize themselves from fascism by becoming more

conservative. Nearly everywhere, the interwar years were a time of nationalism,

red-baiting, and eugenics. Antisemitism and race-mongering were normal. There

was only one place in Europe that fended off the fascist turn with substantial

social reforms: the Kingdom of Sweden, where the Social Democratic party won

the vote in 1932. Of course, this solid left regime only could thrive as a

neutral power, as a niche at the edge of the New Order, supplying the German

war machine with coal and steel.

Ultimately,

it was the rising hegemons, the United States and the Soviet Union, which had

the strongest interests in battling Nazi-Fascist hegemony: the Soviet Union

because it was in the direct line of Nazi aggression; the United States because

it opposed German and Italian, allied with Japanese expansionism around the

global. But it still took years for New Deal America, the troglodyte British

Empire, and Stalin’s walled-off USSR to overcome their differences and forge a

functioning antifascist military alliance.

Fascism

was not fully vanquished by the military victories of World War II alone.

Preventing its revival required a big rethink of economic and political

principles around the world. It called for big projects, for huge investments,

and for government planning to bring about economic recovery. How could a

nation’s subjects be citizens if they were excluded by their poverty, and by

caste-like differences in their education, standards of living, and life

prospects? How could enhanced productivity, and big profits from new

mass-industrial technologies like cars and radios, be more equitably

distributed? Capitalism had to accept regulation. Old-fashioned liberalism had

to accept labor reform and state spending on social benefits. Europe, if it was

to end its warring divisions, had to accept some kind of federalism. The Catholic

Church had to resolve its theological ambivalence and champion human rights

universally, not only for Christians. Socialism (and communism) had to become

more patriotic and reformist. World government had to become stronger, fairer,

and more universal.

The

substance, then, of fascism, but also of anti-fascism, is what mattered about

fascism—not the label of “fascism” that obsesses so many people and dominates

our politics today. That focus on substance is what we need now in the U.S. as

we face not fascism, but rather a crisis of a kind that historic fascism

invented itself to address, in the most awful ways. In this crisis, we need to

summon up the terrifying honesty to address our nation’s responsibility for the

crumbling of the liberal international order, and, if history serves, to create

Popular Front forms of collective action nationally and globally with the power

to confront our many challenges—ideally, well short of new wars.

What We

don’t Understand about Fascism. Using

the Word Incorrectly Oversimplifies History—And Won't Help Us Address Our

Current Political Crisis. By Victoria de Grazia. Zocalo Public Square, August 13, 2020.

Mussolini's

Italy and the perfect fascist

Attilio

Teruzzi was a decorated military hero who rose to power to become a close

associate of Mussolini. But this high ranking official in charge of the black

shirts is really a mediocre man and his personal life is a complicated mess.

Late

Night Live. With Phillip Adams. Guest

Victoria de Grazia, Moore

Collegiate Professor of History, Columbia University. Australian Broadcasting Corporation , August

27, 2020.

"The

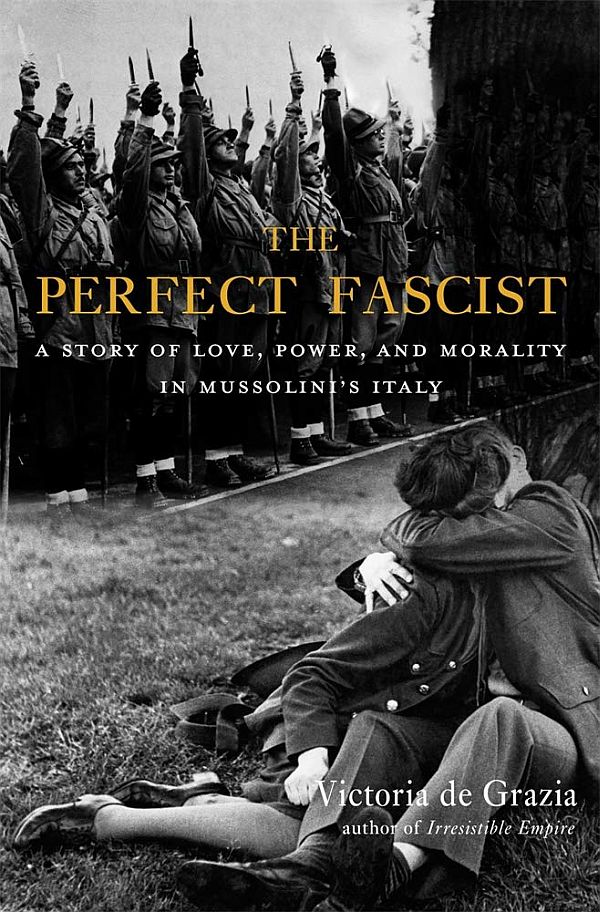

Perfect Fascist" (Harvard University Press, 2020) tells the story of

Attilio Teruzzi, an Italian army officer who became a commander of the

Blackshirts and a colonial administrator under Mussolini. The book analyzes,

through Teruzzi's career and personal history, the inner workings of Italian

fascism. It also explores the issues of ultra-nationalism, strong men, and

racial conflict, which remain sadly relevant in today's political discourse.

Panelists

: Victoria de Grazia (author), Moore

Collegiate Professor of History, Columbia University ; Rachel Donadio,

Contributing Writer, The Atlantic ; Susan

Pedersen, Morris Professor of British History, Columbia University ; Alexander

Stille, San Paolo Professor of International Journalism, Graduate School of

Journalism, Columbia University. Moderator

: Adam Tooze, Kathryn and Shelby Cullom

Davis Professor of History and Director of the European Institute, Columbia

University

Book

launch, European Institute, Columbia University on September 29, 2020.

Mostly

neglected by history, Teruzzi was always close to Mussolini, physically and

ideologically. The enforcer of discipline among the Fascist Blackshirt militia,

he played a pivotal role in the march on Rome in 1922 which brought Mussolini

to power. In his private life Teruzzi would emerge as an ineffectual man in

many ways, clinging to large female figures whenever he could and then cheating

on them. A man created by a bella figura obsessed, parvenus petit bourgeois

mammista culture.

Victoria

de Grazia, Moore Collegiate Professor of History at Columbia University, has

written landmark works on Fascist Italy, notably The Culture of Consent – Mass

Organization of Leisure in Fascist Italy (1981), and How Fascism Ruled Women

1922-1945 (1991). In her latest book, The Perfect Fascist. A Story of Love,

Power, and Morality in Mussolini’s Italy, Prof. de Grazia uncovers an

extraordinary story of unconventional love and politics during Italy’s Fascist

regime. It focuses on the political career of ex-military officer Attilio

Teruzzi, who became one of Benito Mussolini’s most prominent executors. It also

tells the very intimate tale of Teruzzi’s love for, and troubled marriage with,

the beautiful, young and ambitious New York Jewish opera singer, Lilliana

Weinman. But this is not the only obscure side to Teruzzi that de Grazia

uncovers. Teruzzi’s public life has also largely escaped historical analysis

despite the fact that it spanned the whole tragic arc of the regime at the

highest levels.

In this

interview with Victoria de Grazia we learn more about how the book came to be

written, and more fascinating facts about Teruzzi. De Grazia spent twelve years

piecing together both the private and public vicissitudes of Lilliana and

Attilio’s relationship set against the backdrop of Fascism’s precipitous rise

and ruinous fall. It is also illuminating to consider the parallels between

fascism in Teruzzi’s day and its resurgence today.

Victoria,

how did this book come about?

VdG “It

was one of those almost apocryphal events that is quite serendipitous: a very

educated woman, a relative of Lilliana Weinman, had these bags of her papers

and she was worried that they would be disposed of. So, she approached me to

take a look at them, knowing that I was a historian. Initially, I was

skeptical, but then I was very taken by a photograph of Mussolini taken at

Lilliana’s wedding. And then there were many photographs of Libya under Italian

colonial rule. The fact that Lilliana was an opera singer also intrigued me as

did the several volumes of their marriage annulment proceedings. Once I latched

onto that and began to ask, ‘who is this? what was this love affair with the

fascist notable that she married’, the story began to unfold and it became more

and more interesting as I continued the research.”

Why do

you think that Attilio Teruzzi has been so neglected by historians as a major

figure in Fascist Italy? Why are you the first historian to write a book about

Teruzzi?

VdG “It

is remarkable that no one has really written about Teruzzi. Sometimes greater

familiarity with a person breeds contempt and you can see that in opinions

regarding Achille Starace (Secretary of the Fascist National Party from

1931-1939) who was always in the public view and is often treated like a clown

by historians. Historians have preferred to focus on outstanding Fascist

leaders like Italo Balbo (Minister of the Air Force 1929-1933 and Governor

General of Libya 1934-1940) who was dashing and impertinent, or the pro-Nazi

Roberto Farinacci (Secretary of the Fascist National Party 1935-1936), who left

a lot of papers, because he had his own newspaper and a great amount of

correspondence.

Then we

have the diaries of Galeazzo Ciano (Minister of Foreign Affairs 1936-1943),

Mussolini’s son in law, which are also highly important. Historians also

haven’t been able to access some very important sources, which would have made

Teruzzi a more central figure. For one, the Fascist Blackshirt militia records

have been lost.

Secondly,

only recently has the German Historical Institute of Rome digitized Mussolini’s

Appointment Calendar from 1923–1943. Until now biographers of Mussolini have

not been able to document who visited him every day: we know now that Teruzzi

was a regular presence. The immense photographic archives of the Istituto Luce

reveal just how prominent Teruzzi was. He’s always standing straight and close

to Mussolini. There’s a lot of physical proximity between them.”

What

sort of man was Teruzzi?

VdG “Attilio

Teruzzi was born in Milan in 1882 into a relatively modest lower middle class

family. After losing his father at a young age he opted for a military career.

He served in Eritrea, at the time an Italian colony, and later attended Italy’s

version of West Point, the Military Academy of Modena. Teruzzi’s subsequent

success in his career was largely due to intelligence and merit. He fought in

Italy’s war to make Libya a colony in 1911-1914 and subsequently in the First

World War, distinguishing himself and winning medals for bravery under fire.

After demobilization he joined the Fascist movement in its early stages,

enforcing discipline among the Fascist Blackshirt militia and playing a pivotal

role in the march on Rome in 1922 which brought Mussolini to power.”

How

competent was Teruzzi as a political leader?

VdG “In

his military life Teruzzi was a very good battalion major and in another era he

would excelled in a big bureaucracy such as a railroad company. Fascist Italy

took him to another level. Even so, he acquitted himself quite well. In

Cyrenaica he could be considered a brilliant choice: he was one of the very few

competent colonial men of the regime. Between 1929 and 1935 he was the head of

the Fascist Blackshirt Militia, a 350,000 strong force that reported directly

to the Duce, making his position one of the highest in the fascist political

hierarchy.

This

entrusted him with what was becoming the most important mission of the regime,

to transform the armed guard of the Fascist revolution, the Blackshirts, into a

formidable fighting force. During the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, for

example, he successfully led a Blackshirt Division tasked with making roads:

not a glamorous role, but a fundamental one in a country that had little

infrastructure. Teruzzi’s time in service was probably the longest of

anybody’s. He survived various calls for him to resign because of corruption.

And Teruzzi certainly messed around: he was a libertine. He gave lots of gifts

to people. He was a man of the Empire, who seemed to be luxuriating in coffee,

you know? He was such a perfect target for melodrama, and there was always

melodrama. So Teruzzi was targeted in disproportion because he got some things

done and not others.”

Let’s

look at his personal relationship with Lilliana. When did he meet her and what

sort of woman was she?

VdG “In

1924 Teruzzi became a parliamentary deputy for the Fascist Party and

undersecretary for the Ministry of the Interior. It was at this point that he

began to court a young opera singer freshly arrived from New York: Lilliana

Weinman. She was an aspiring opera diva from a prosperous New York Jewish

family. A physically imposing woman, she was attractive, ambitious and much

younger than Teruzzi. After an assiduous courtship she and Teruzzi married in

1926. Mussolini was the witness. Lilliana abandoned her promising opera career

and dedicated herself to her husband’s career, which included a stint in

Italy’s Libyan province of Cyrenaica between 1926 and 1928. In the book I cite

her cousin who stated: “Lilliana liked the red carpet, she didn’t like to look

under it.” And by this, I mean that there is no trace of her expressing

misgivings about the politics of regime, including its colonial wars. This was

despite the fact that she ended up embroiled in the intricacies of Italy’s hypocritical

marital laws after Teruzzi suddenly and unilaterally decided to annul their

marriage.”

Did

Teruzzi manage to have his marriage to Lilliana annulled?

VdG “Well,

the fact that she strenuously and definitively blocked the annulment of her

marriage, which was regulated by Church law at the time, gives you some

indication of what a formidable character she was. And she never stopped using

her husband’s surname. When people addressed her as Contessa Teruzzi, she never

corrected them! In the book I muse on whether Lilliana could be considered the

heroine of the story. But in many ways, she could also be considered the

heroine manquée of this saga.”

How

would you characterize Teruzzi as a person rather than as a politician?

VdG “We

can get a glimpse at his character from his reaction when he was appointed head

of the Fascist militia in 1928: he starts crying and gets very sick because he

was forced to leave his beloved Libya. If they had made a film on his life some

time ago it would have to be played splendidly by Marcello Mastroianni or

Vittorio Gassman. Or in a more recent rendition he would have been an ideal

subject for a Lina Wertmüller film played by Giancarlo Giannini with his liquid

and tearful eyes. Teruzzi would emerge as an ineffectual man in many aspects of

his private life, clinging to large female figures whenever he could and then

cheating on them. A man created by a bella figura obsessed, parvenus petit

bourgeois mammista culture.”

In 1912

the famous Italian historian-philosopher, Benedetto Croce, theorized that, ‘All

History is Contemporary History’. How does this relate to your book?

VdG“I

started this research when Silvio Berlusconi, the Italian media tycoon who

became the Prime Minister of Italy, was still around. He exemplified a run of

new political types that came to the fore as party systems broke down in the

wake of 1989. Before that time a kind of equilibrium existed between

center-right and center-left. We began to see the denouement of this breakdown

some 15-20 or even 25 years later with the rise of the early 21st century

strongmen such as Vladimir Putin. At the time I was thinking: ‘It would be so

wonderful to drive a stake through the political heart of Berlusconi.’

Subsequently, I thought my research would lead me to some sort of transcendent

truth about how these strong men act and cocoon themselves in privilege. Their

entitlement, guaranteed by the state apparatus, shows them up as weak men who

rely on retinues, privileges and policing to stay in power. This dynamic applies

even to smaller bureaucracies such as universities. So, leaders often let

things go at the same time as they aggrandize the capacities needed to do their

jobs.”

Today

the term ‘Fascist’ is bandied around quite a bit, even on social media. You’re

a scholar specializing in the fascist period, so what are your thoughts on the

current use of the term?

VdG “Very

commonly you hear right leaning people being called fascist from the left. And

there’s also a sense that the liberal global order is cracking or has cracked

apart and that we have got new movements that seem as terrifying or

disorienting as we think Fascism was in the 1920s. So, you get many people who

work with typologies, historians, political scientists who say: ‘Look if we

understand such and such then we can decide whether this is a real Fascism or

this is something else.’ I don’t find that interesting at all. I don’t think

they have any predictive models, and I don’t think they know very much history

either with rare exceptions like Robert Paxton, whose typology is actually very

flexible and really is an account over time. This approach underscores the

opportunism of fascist movements that are changing all the time. In Italy

Fascism was neo-liberal in the 1920s, then mercantalist, only to become an

Autarchic imperialist warmongering regime in the 1930s. In these extreme times,

I think that we need to get people to think about how a movement that wants

power legitimates itself and then acts. You can see over time certain political

actors at work. And basically, you’re saying: ‘Wow, I’m now more informed

because I’ve seen how it was active then. They were called fascists, and I

could see how they were acting.’ They could be called Putinists, or Orbanists

or whatever. They could be like the current head of the National Party in

France, a woman who believes in the French national welfare state. But we

shouldn’t get caught up by saying: ‘Wow, this is Fascism.’ Then we’ll be able

to identify fascists today or from what we see today. We will have some predictive

understanding of today and tomorrow by looking back onto the past.”

Why did

you choose the title The Perfect Fascist?

VdG “I

titled the book The Perfect Fascist because you could say every era has its

perfect fascist. But you don’t have to call anyone a perfect fascist. One could

call them a perfect Trumpist a perfect Putinist, the perfect whatever. You can

understand this mechanism of total power, this effort to exercise a totalizing

kind of power which is good for the leader and for the leader’s followers.

Power which they say is absolutely paramount to keep the nation on keel. So

that that’s pretty much where I stand here, I don’t think we should be drawing

lessons from that, rather we should be drawing a kind of sensitization in

thinking about politics. I do think you can get that from my book. But not a

catechism.”

Attilio

Teruzzi: “The Perfect Fascist”. Today This Could Be a Trumpist or a Putinist

Interview

with Professor Victoria De Grazia, author of "The Perfect Fascist. A Story

of Love, Power, and Morality in Mussolini’s Italy". By Gerardo Papalia. La Voce di New York, November 19, 202

It was

dubbed as a “Fascist Wedding in Rome” by the society page of The New York

Times. The unlikely marriage between Attilio Teruzzi, an army officer and one

of the rising stars of the Italian fascist movement, and Lilliana Weinman, an

American Jewish opera singer, took place in June 1926.

Benito

Mussolini, the supreme leader of Italy and the head of its fascist party, was

Teruzzi’s best man.

The

governor of Rome officiated at their civil ceremony, which was followed by a

church wedding at the Basilica of Saint Mary of the Angels. Six hundred guests

attended the glittering reception.

It

didn’t seem to matter to Mussolini that Weinman, whose stage name was Lilliana

Lorma, was Jewish. After all, Mussolini’s lover, Margherita Sarfatti, was

Jewish, too. As far as he was concerned, Weinman was an American, period.

Antisemitism would become a menacing factor in Italy only in the late 1930s. So

for now, Weinman’s Jewishness was not an issue.

Three

years later, after Teruzzi’s appointment as national commander of the

Blackshirts, the paramilitary force that protected Mussolini’s regime, he

renounced his marriage, claiming she had betrayed and dishonored by his bride.

Since Italy had no divorce law, he sought an annulment, but Weinman stubbornly

resisted.

Their

tempestuous relationship, along with Teruzzi’s dazzling career and his affair

with another woman of Jewish descent, form the backbone of Victoria de Grazia’s

splendid work, The Perfect Fascist: A Story of Love, Power, and Morality in

Mussolini’s Italy, published by Harvard University Press.

Born in

Milan in 1882, Teruzzi was an arresting figure. An affable socializer and

horseman who played tennis and fenced, he was a dandy who could speak French

and had a taste for gorgeous dress uniforms. Like many European military

officers of that era, he groomed his facial hair meticulously, favoring a

moustache, sideburns and a beard.

Having

fought in a colonial war in Libya and in World War I, he joined the fascists in

December 1920, before Mussolini’s ascent to power. Elected to parliament in

1924, Teruzzi was promoted to the powerful position of undersecretary of state

of the Ministry of Interior in 1925. A year later, he served as governor of the

Libyan province of Cyrenaica. In 1928, he was appointed commander of the

350,000-strong Blackshirts. On the eve of World War II, he was named the

minister in charge of Italian colonies in Africa.

Mussolini

valued Teruzzi, calling him “a soldier and fascist, valorous in the Great War

and loyal in every moment of the fascist revolution.” In short, he was “a

perfect fascist,” writes de Grazia, a professor of history at Columbia

University.

Teruzzi

met Weinman in 1920 in Milan, where she was completing her operatic studies.

But their courtship really began in 1925.

De

Grazia has a high opinion of Weinman, whose wealthy parents, Isaac and Rose,

hailed from the southern Polish city of Rzeszow. As she puts it, “Lilliana

believed in her art, hard work, and the success arising from both. Unlike the

Italian woman of aristo-bourgeois wealth, she had no family estates, no stash

of ancestral porcelain and silver plate, baroque paintings, or antique furniture.

She was the pure product of America’s grand experiment in meritocracy, entirely

self-made, deservedly successful and thus a demonstrably superior person.”

De

Grazia says that one of her mentors was Tullio Serafin, Arturo Toscanini’s

successor at the La Scala opera house.

A

secular Jew, Weinman did not have to convert to Christianity to marry Teruzzi.

She received a special dispensation from the Catholic Church after promising to

study catechism, baptize their children, and uphold her husband’s religious

inclinations.

Interestingly

enough, she was not his first Jewish girlfriend. While serving in Libya, he

fell in love with a Jewish woman, the daughter of a merchant or cafe owner.

After

the collapse of his marriage, Teruzzi met Yvette Maria Blank, supposedly a

Coptic Christian who, in fact, was Jewish. He couldn’t marry Blank since he was

legally married to Weinman, but they had a daughter, Celeste, who was born out

of wedlock in 1938. As Italy’s alliance with Nazi Germany tightened and as Italy

restricted the civil rights of Jews, Blank’s racial origins developed into a

sensitive problem.

Once

Weinman and Teruzzi parted ways, Weinman’s status as a Jew came into play.

Teruzzi’s defenders made the case that he had been tricked into the marriage by

a seductive and treacherous Jew. Weinman, however, did not believe her husband

was anti semitic.

De

Grazia takes a middle-of-the-road approach to this issue. After the Italian

government passed its first antisemitic laws in 1938, he tried to help some Italian

citizens of Jewish or partial Jewish descent. But in 1942, having come under

increasing pressure to show his antisemitism, he decreed that Libyan Jews

should be subjected to exactly the same restrictions as Jews in Italy.

The

Italian fascist movement treated Jews as equal citizens for almost the first 20

years of its existence. But in the wake of Adolf Hitler’s visit to Italy in May

1938, the Fascist Grand Council approved a package of antisemitic legislation,

which was passed by the Council of Ministers and signed into law by the king on

November 11, 1938, a day after the Kristallnacht pogroms in Germany. The Roman

Catholic Church did not oppose these harsh limitations on Jewish rights.

Among

the Jews affected by the race laws was Mussolini’s office manager, Jole Foa,

who had been a loyal employee for 12 years, and Mussolini’s Jewish mistress,

Margherita Sarfatti, who was forced into

exile.

Weinman

left Italy for good in 1938, returning to her home in New York City, where she

joined the family business. She visited Italy after the war, but her romance

with it had dissipated. She paid her visit in 1953.

She

refused to grant Teruzzi an annulment on principle, claiming there had never

been a divorce in her family. De Grazia doesn’t buy her rationale: “Lilliana

saw no paradox at all in an American Jew fighting the Catholic Church to defend

her right to preserve her marriage with a cad and a fascist, a declared

antisemite, and an enemy of her country.”

Teruzzi’s

career flourished during the first years of the war. He attained the rank of

general, and in 1940, following Germany’s conquest of France, Hitler granted

him a meeting. While in Berlin, he conducted talks with Reinhard Heydrich, one

of the highest-ranking SS officials.

The

anti-fascist movement declared Teruzzi guilty of war crimes after Allied troops

liberated Rome in June 1944. Captured in northern Italy by partisans, he was

placed on trial. He received a 30-year prison sentence and his properties were

confiscated.

He spent

the next five years in jail on the island of Procida, and was released in March

1950. Within a few days of being set free, he was diagnosed with congestive

heart failure. He died in April of that year.

Weinman,

known as the Countess Attilio Teruzzi, passed away in 1987, the widow of the

perfect fascist.

The

Perfect Fascist. By Sheldon Kirshner. Sheldon Kirshner Journal , September 1, 2020.

As we

all hunkered down in our respective

abodes to socially distance at the dawning of the age of COVID-19, some of us

learned how to make sourdough bread, others picked up knitting, and still

others turned to Animal Crossing. I tried all these and I failed at all. So I

am a COVID-19 hobby failure. Except I did become an expert in Netflix, Amazon

Prime Video, Hulu, and other streaming platforms. I have watched just about

every sappy Korean teen soap opera out there. But one genre has fascinated us

above all others, and it’s not a virus-generated interest: the first season of

American Crime Story, the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman, and

the trial of football legend O. J. Simpson. And then we devoured the second

season when we witnessed Andrew Cunanan murdering five people, including

fashion designer Gianni Versace, in 1997. Add to that the new Netflix

documentary on Jeffrey Epstein and the popular award-winning Making a Murderer

series that documented the story of Steven Avery that led to a petition to the

White House for an official pardon (something the president could not do as he

could not intervene in a state criminal offense) signed by over 500,000 people.

Clearly, the American public has a fixation on understanding the minds of

criminals, murderers, and others featured in the infamous rogues’ gallery.

So it

should come as no surprise that Victoria de Grazia’s captivating investigation

into the trials and tribulations of Attilio Teruzzi — one of Benito Mussolini’s

most trusted high-ranking officials, who suffered the tensions of a convenient

and then utterly inconvenient marriage, loyalty to il Duce and the fascist

dictates, and then an utter failure to adhere to them in matters of the heart —

should thrill this reader who had become perhaps too much an expert in crime

and psychological thrillers. Of course, The Perfect Fascist: A Story of Love,

Power, and Morality in Mussolini’s Italy is not an intellectual’s Italian Crime

Story or Making a Fascist: this is a work of serious historical research by one

of the great historians of Italian history. And, as de Grazia reminds us, the

book is no simple biography. It is a microhistory of one man’s journey, one

man’s decisions as he navigated the complicated, chaotic, confusing, sometimes

nonsensical, often racist, misogynist, nativist, populist, oft-changing agendas

and alliances of the fascist regime. The book illuminates not just the much

broader dictatorial, ultra-nationalistic systems in place in Italy during the

1920s, ’30s, and ’40s, but also the very human and individual characteristics

of the players and the victims — all agents in this theater — that rendered

Italian fascism so impactful.

Atillio

was in line to be “the perfect fascist”: the “archetypal virtuous warrior of

the imperial West [who] invites us to consider how individuals, in their lusts

and longing, in their dreams and prejudices and petty quarrels, are swept up

and reshaped by the course of history.” As de Grazia explains, her book is “a

social history of a man who as he makes his way, in the complexity of his

political and human relations, often captured from the vantage point of his

women, shows us how Italian fascism really worked.” Attilio’s story is nothing

if not complex. Even for a member of the decision-making elite, the ground was

constantly shifting, and his standing in the Partito Nazionale Fascista

vulnerable. The Perfect Fascist contextualizes the personal — the sordid, the

intimate — within the political framework of the grounding of the Fascist

Party: its authoritarian, yet completely legal takeover of the Italian

political systems, and its aggressions in World War II. But the story is so

juicy, the affairs so unexpected, the narrative so rich, the analysis so

intricate, that, with all its historical rigor, it reads — as Eddie Izzard

describes the druids in Dressed to Kill — in an “interesting night-time telly

sort of way.”

Italy’s

reckoning with its fascist past is complicated. The brava gente (“good people”)

trope went a long way in stopping substantive conversations about antisemitism,

racism, nativism, ultra-nationalism, and state terrorism. “Well, we were

fascists, but we weren’t Nazis. We were brava gente,” became the pseudo-battle

cry when Italians were asked to explain their part in the Nazi persecution and

ultimate annihilation of European Jews. So how do we negotiate the trajectory

of a person like Attilio, who became a lieutenant general and inspector general

of the Blackshirts during the Spanish Civil War after having served in Italy’s

army during its quest for empire in the 1911 Libya campaign? For some, the

brava gente mythology applied just as well to fascism as it did to defuse the

well-documented brutality of the Italian imperial campaigns in Eritrea, Libya,

and Ethiopia. We cannot help but wonder: Did someone like Attilio carry his

membership in the brava gente from 1937 to 1939, when he served as

undersecretary in the Ministry of Italian Africa, and when he was promoted to

minister from 1939 to 1943? Does ambition lessen his complicity in the

teleology of racism, imperialism, and fascism?

When I

first began my studies on race, nation, and the “Southern question” (the

historic cultural, social, economic, and perceived racial divide between

Northern and Southern Italy) as a graduate student, I was admonished by a

senior faculty member to “study my own skin.” (I am, for the record, a proud

Chinese American scholar of Italian history.) Then, later, when I was a

graduate student on my first Fulbright, I visited one of the foremost scholars

of Italian Unification. After hearing my dissertation three-minute elevator

pitch about my work on the use of the racialized “Southern question” metaphor

to describe other notions of difference, he asked me if I really needed to

“travel all the way to Italy to study racism when it was so rampant in [my] own

country.” We should not pretend, then, that the brava gente myth is anything

other than a myth. Race is not a secondary theme to the more strident and

forceful strains of the fascist refrain. It has been, and always will be, the

underlying chord that defines nativism and authoritarianism. While de Grazia

skillfully teases out the man, the soldier, the officer, the husband, the

lover, the lothario, the ambitious politician who climbed the vicious ladder of

the fascist patriarchy, she never shies away from the more difficult

conversations about the ruthlessness of the populist regime: its xenophobia,

misogyny, racism, and antisemitism, the use of propaganda and misinformation,

the preying on fear of the other, of change, and the empowering of those who

felt vulnerable, unheard, disrespected, disenfranchised in the post–World War I

era.

And yet,

even as de Grazia traces the choices of Attilio the politician, what anchors

the book is an intimate, personal story. It is not unlike the popular thrillers

on Netflix in its suspense and surprises, but this story is told with a

scholar’s eye in reading, analyzing, and interpreting archival documents, and a

historian’s experience in placing it all within the context of Mussolini’s

Italy.

When

Attilio chose, in 1926, to marry a woman whom we might call an early

20th-century “influencer” — a beautiful American opera singer, Lilliana

Weinman, the daughter of a wealthy family of Polish Jewish origin — it looked

as though both his professional and his love life was off to a promising start.

Benito Mussolini himself attended the festivities, and celebrated the promessi

sposi (à la Alessandro Manzoni and his 19th-century germinal novel) when they

became simply sposi (married). To top it all off, il Duce stood front and

center in the Teruzzi marriage portrait, right smack between the Jewish

mother-of-the-bride and the Jewish bride herself. Eerie and perhaps ominous

when you consider that just three years later, in 1929, Attilio would seek an

annulment. In 1939, 10 years after the annulment was filed, Mussolini would

sign the Pact of Steel, sealing the military-political alliance between fascist

Italy and Nazi Germany on the eve of the World War II. Thus, while the

annulment would wind its ways through the Catholic Church for two decades, the

antisemitic policies of Italy would allow Attilio to use Lilliana’s Jewish

origins and then her American citizenship (the entry of the United States in

the war made them enemies of the Italian state) as reasons for the separation.

Some Italians may argue that it was the alliance with Germany that brought the

rhetoric of racism to the peninsula, but make no mistake: race and racial

origin were already very much a part of the fascist discourse. Even before the

racial laws of 1938, official Italian bureaucratic documents often asked about

the race of the person filling out the forms. The correct answer for Italians

was simple: Aryan. While Lilliana herself had never known her husband to hold

antisemitic beliefs, he was not below falling along party lines if it might

help with the adjudication of his request for annulment.

De

Grazia began this research at the behest of the Weinman family, who wanted to

understand how Lilliana, a rising star in the opera world (a world she would

remain connected to by sponsoring the $2,500 Teruzzi Award in the 1960s, and

then presenting the awards to winners of the Metropolitan Opera competition

from 1965 to 1969), with a forthright and bold voice, operatic and otherwise,

from a proud Polish Jewish family, would choose to abandon her career and marry

a rising fascist with a big, bushy beard (the beard will play a role in the

popular attempts to have Teruzzi meet his ultimate demise).

De

Grazia quickly grasped that Lilliana might be pivotal not only in revealing the

inner workings of the heart, but in understanding the motivations of a fascist

who marries a Jewish woman, annuls that marriage, and then goes on to have an

affair with a second Jewish woman. This second woman, whom Attilio met in late

1936, was Egyptian-born Yvette Maria Blank. De Grazia describes her as a

“Levantine” beauty with “something racially exotic about her sweet, animated

face, strong nose, intense eyes, and thick cap of dark, wavy hair […] Was she

Turkish? Levantine? Egyptian? Some combination of the above?” Or was she, as

the spies and informers who did the background checks for Attilio concluded, a

Romanian woman, but one who spoke no Romanian and was a Coptic Christian to

boot? Her father had identified as Jewish until he converted upon marriage. De

Grazia points out that Yvette’s mother, Corine Schmill, was an implausible

Coptic Christian. She was a mysterious woman of mysterious origins, and surely

the question of her Jewishness must have raised some eyebrows. None of this

mattered for the besotted Attilio. By January 1938, Yvette was pregnant and

would, in September of that year, give birth to a much-loved daughter whose

birth certificate would list the father as “Unknown” (because Attilio was still

legally married to Lilliana), and would carry her mother’s surname Blank rather

than Teruzzi.

De

Grazia’s coup de grâce is to have weaved together into one coherent whole so

many narrative threads: the story of the long longed-for annulment from an

American opera singer of Jewish Polish origins, the story of this second,

ill-fated love affair with a “foreign,” “Other-ed” Jewish mother of his child,

the attempts to eradicate and then conceal and then adopt and then make Italian

his daughter, all unfolding within, without, informing, and informed by the

rise and fall of the fascist regime. Lilliana, the opera singer, may have got

more than she had ever bargained for: she found herself in the middle of an

Italian lyrical opera with all its drama, illnesses, deaths, misunderstandings,

concealed identities, and family secrets. This story has all the elements of a

thriller — the psychological drama that reveals the inner workings of fascist

criminal minds — with all the soap opera twists and turns: an annulment process

that lasts two decades, an escape to America from Nazi persecution, the selling

of one’s soul to the fascist devil to advance professionally, two wives — one

legal, the other of the heart, a disowned then recognized “bastard” daughter,

detention and concentration camps, blackmail, intrigue, lynchings. When

Mussolini was executed (and his body lost and then found and then strung up by

his feet at a gas station for the Italian public to stone), the crowd mistook

the heavily bearded man hanging next to him for Teruzzi. They were wrong that

time, just as they would be wrong many more times as several unfortunate

big-bearded men were lynched at the end of the war in cases of mistaken

identity. And did I mention sex? There is lots of it in the story. It’s the

Kardashians, The Godfather, fascism, Nazis, a little Jersey Shore, and Vatican

shenanigans all rolled into one.

We

likely have many more months of COVID-19 ahead of us, and depending on what

happens in the November elections, a few more months or several more years of

anti-intellectualism and, as Tom Nichols coins it, the death of expertise.

Victoria de Grazia has offered us a historical escape, one that speaks directly

to pandemic hobbies. You are being warned, as you turn page after page of her

book, of the price we pay when ambition outweighs conscience, when ego eclipses

community, when fascism and populist authoritarianism disguise themselves as

originalist democracy, when private wealth is privileged over public good. We

are reminded, as we read this tale of the perfect fascist who faced the

imperfections of his own heart and his party, that Mussolini came to power

legally in an appointment by the then-king of Italy, and that that legality

allowed people like Attilio to support and even idolize the man-who-would-become-dictator

with an alleged clear conscience. And we are warned that we are not reading or

watching or chilling “in an interesting night-time telly sort of way.” If we do

not vote, if we do not dissent, if we do not resist, if we do not persist, we

are the ones who will be living this hellscape reality show that will last far

beyond 2020.

For a

More Perfect Fascism: On Victoria de Grazia’s “The Perfect Fascist”. By Aliza

Wong. Los Angeles Review of Books , November 3, 2020.

No comments:

Post a Comment