One Art

The art

of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose

something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

Then

practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost

my mother’s watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

I lost

two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

—Even

losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.

I love) I shan’t have lied. It’s evident

the art of losing’s not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

Letter

to N.Y.

For Louise Crane

In your next letter I wish you'd say

where you are going and what you are doing;

how are the plays, and after the plays

what other pleasures you're pursuing:

taking cabs in the middle of the night,

driving as if to save your soul

where the road goes round and round the park

and the meter glares like a moral owl,

and the trees look so queer and green

standing alone in big black caves

and suddenly you're in a different place

where everything seems to happen in waves,

and most of the jokes you just can't catch,

like dirty words rubbed off a slate,

and the songs are loud but somehow dim

and it gets so terribly late,

and coming out of the brownstone house

to the gray sidewalk, the watered street,

one side of the buildings rises with the sun

like a glistening field of wheat.

—Wheat, not oats, dear. I'm afraid

if it's wheat it's none of your sowing,

nevertheless I'd like to know

what you are doing and where you are going.

For Louise Crane

In your next letter I wish you'd say

where you are going and what you are doing;

how are the plays, and after the plays

what other pleasures you're pursuing:

taking cabs in the middle of the night,

driving as if to save your soul

where the road goes round and round the park

and the meter glares like a moral owl,

and the trees look so queer and green

standing alone in big black caves

and suddenly you're in a different place

where everything seems to happen in waves,

and most of the jokes you just can't catch,

like dirty words rubbed off a slate,

and the songs are loud but somehow dim

and it gets so terribly late,

and coming out of the brownstone house

to the gray sidewalk, the watered street,

one side of the buildings rises with the sun

like a glistening field of wheat.

—Wheat, not oats, dear. I'm afraid

if it's wheat it's none of your sowing,

nevertheless I'd like to know

what you are doing and where you are going.

Little

Exercise

for Thomas Edwards Wanning

Think of

the storm roaming the sky uneasily

like a dog looking for a place to sleep in,

listen to it growling.

Think

how they must look now, the mangrove keys

lying out there unresponsive to the lightning

in dark, coarse-fibred families,

where

occasionally a heron may undo his head,

shake up his feathers, make an uncertain comment

when the surrounding water shines.

Think of

the boulevard and the little palm trees

all stuck in rows, suddenly revealed

as fistfuls of limp fish-skeletons.

It is

raining there. The boulevard

and its broken sidewalks with weeds in every crack

are relieved to be wet, the sea to be freshened.

Now the

storm goes away again in a series

of small, badly lit battle-scenes,

each in "Another part of the field."

Think of

someone sleeping in the bottom of a row-boat

tied to a mangrove root or the pile of a bridge;

think of him as uninjured, barely disturbed.

for Thomas Edwards Wanning

like a dog looking for a place to sleep in,

listen to it growling.

lying out there unresponsive to the lightning

in dark, coarse-fibred families,

shake up his feathers, make an uncertain comment

when the surrounding water shines.

all stuck in rows, suddenly revealed

as fistfuls of limp fish-skeletons.

and its broken sidewalks with weeds in every crack

are relieved to be wet, the sea to be freshened.

of small, badly lit battle-scenes,

each in "Another part of the field."

tied to a mangrove root or the pile of a bridge;

think of him as uninjured, barely disturbed.

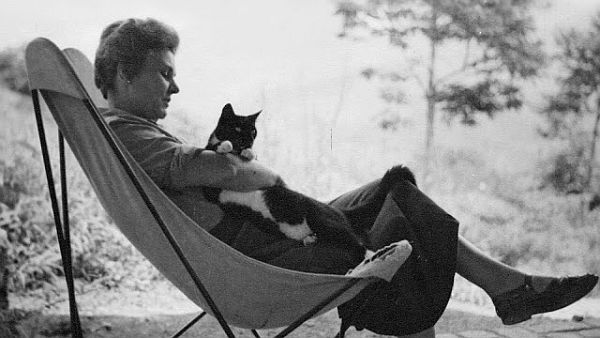

Lullaby

For the Cat

Minnow, go to sleep and dream,

Close your great big eyes;

Round your bed Events prepare

The pleasantest surprise.

Darling Minnow, drop that frown,

Just cooperate,

Not a kitten shall be drowned

In the Marxist State.

Joy and Love will both be yours,

Minnow, don't be glum.

Happy days are coming soon —

Sleep, and let them come…

Minnow, go to sleep and dream,

Close your great big eyes;

Round your bed Events prepare

The pleasantest surprise.

Darling Minnow, drop that frown,

Just cooperate,

Not a kitten shall be drowned

In the Marxist State.

Joy and Love will both be yours,

Minnow, don't be glum.

Happy days are coming soon —

Sleep, and let them come…

In the

Waiting Room

In

Worcester, Massachusetts,

I went with Aunt Consuelo

to keep her dentist's appointment

and sat and waited for her

in the dentist's waiting room.

It was winter. It got dark

early. The waiting room

was full of grown-up people,

arctics and overcoats,

lamps and magazines.

My aunt was inside

what seemed like a long time

and while I waited I read

the National Geographic

(I could read) and carefully

studied the photographs:

the inside of a volcano,

black, and full of ashes;

then it was spilling over

in rivulets of fire.

Osa and Martin Johnson

dressed in riding breeches,

laced boots, and pith helmets.

A dead man slung on a pole

--"Long Pig," the caption said.

Babies with pointed heads

wound round and round with string;

black, naked women with necks

wound round and round with wire

like the necks of light bulbs.

Their breasts were horrifying.

I read it right straight through.

I was too shy to stop.

And then I looked at the cover:

the yellow margins, the date.

Suddenly, from inside,

came an oh! of pain

--Aunt Consuelo's voice--

not very loud or long.

I wasn't at all surprised;

even then I knew she was

a foolish, timid woman.

I might have been embarrassed,

but wasn't. What took me

completely by surprise

was that it was me:

my voice, in my mouth.

Without thinking at all

I was my foolish aunt,

I--we--were falling, falling,

our eyes glued to the cover

of the National Geographic,

February, 1918.

I said

to myself: three days

and you'll be seven years old.

I was saying it to stop

the sensation of falling off

the round, turning world.

into cold, blue-black space.

But I felt: you are an I,

you are an Elizabeth,

you are one of them.

Why should you be one, too?

I scarcely dared to look

to see what it was I was.

I gave a sidelong glance

--I couldn't look any higher--

at shadowy gray knees,

trousers and skirts and boots

and different pairs of hands

lying under the lamps.

I knew that nothing stranger

had ever happened, that nothing

stranger could ever happen.

Why

should I be my aunt,

or me, or anyone?

What similarities--

boots, hands, the family voice

I felt in my throat, or even

the National Geographic

and those awful hanging breasts--

held us all together

or made us all just one?

How--I didn't know any

word for it--how "unlikely". . .

How had I come to be here,

like them, and overhear

a cry of pain that could have

got loud and worse but hadn't?

The waiting

room was bright

and too hot. It was sliding

beneath a big black wave,

another, and another.

Then I

was back in it.

The War was on. Outside,

in Worcester, Massachusetts,

were night and slush and cold,

and it was still the fifth

of February, 1918.

I went with Aunt Consuelo

to keep her dentist's appointment

and sat and waited for her

in the dentist's waiting room.

It was winter. It got dark

early. The waiting room

was full of grown-up people,

arctics and overcoats,

lamps and magazines.

My aunt was inside

what seemed like a long time

and while I waited I read

the National Geographic

(I could read) and carefully

studied the photographs:

the inside of a volcano,

black, and full of ashes;

then it was spilling over

in rivulets of fire.

Osa and Martin Johnson

dressed in riding breeches,

laced boots, and pith helmets.

A dead man slung on a pole

--"Long Pig," the caption said.

Babies with pointed heads

wound round and round with string;

black, naked women with necks

wound round and round with wire

like the necks of light bulbs.

Their breasts were horrifying.

I read it right straight through.

I was too shy to stop.

And then I looked at the cover:

the yellow margins, the date.

Suddenly, from inside,

came an oh! of pain

--Aunt Consuelo's voice--

not very loud or long.

I wasn't at all surprised;

even then I knew she was

a foolish, timid woman.

I might have been embarrassed,

but wasn't. What took me

completely by surprise

was that it was me:

my voice, in my mouth.

Without thinking at all

I was my foolish aunt,

I--we--were falling, falling,

our eyes glued to the cover

of the National Geographic,

February, 1918.

and you'll be seven years old.

I was saying it to stop

the sensation of falling off

the round, turning world.

into cold, blue-black space.

But I felt: you are an I,

you are an Elizabeth,

you are one of them.

Why should you be one, too?

I scarcely dared to look

to see what it was I was.

I gave a sidelong glance

--I couldn't look any higher--

at shadowy gray knees,

trousers and skirts and boots

and different pairs of hands

lying under the lamps.

I knew that nothing stranger

had ever happened, that nothing

stranger could ever happen.

or me, or anyone?

What similarities--

boots, hands, the family voice

I felt in my throat, or even

the National Geographic

and those awful hanging breasts--

held us all together

or made us all just one?

How--I didn't know any

word for it--how "unlikely". . .

How had I come to be here,

like them, and overhear

a cry of pain that could have

got loud and worse but hadn't?

and too hot. It was sliding

beneath a big black wave,

another, and another.

The War was on. Outside,

in Worcester, Massachusetts,

were night and slush and cold,

and it was still the fifth

of February, 1918.

Arrival

at Santos

Here is

a coast; here is a harbor;

here, after a meager diet of horizon, is some scenery;

impractically shaped and—who knows?—self-pitying mountains,

sad and harsh beneath their frivolous greenery,

with a

little church on top of one. And warehouses,

some of them painted a feeble pink, or blue,

and some tall, uncertain palms. Oh, tourist,

is this how this country is going to answer you

and your

immodest demands for a different world,

and a better life, and complete comprehension

of both at last, and immediately,

after eighteen days of suspension?

Finish

your breakfast. The tender is coming,

a strange and ancient craft, flying a strange and brillant rag.

So that's the flag. I never saw it before.

I somehow never thought of there being a flag,

but of

course there was, all along. And coins, I presume,

and paper money; they remain to be seen.

And gingerly now we climb down the ladder backward,

myself and a fellow passenger named Miss Breen,

descending

into the midst of twenty-six freighters

waiting to be loaded with green coffee beans.

Please, boy, do be more careful with that boat hook!

Watch out! Oh! It has caught Miss Breen's

skirt!

There! Miss Breen is about seventy,

a retired police lieutenant, six feet tall,

with beautiful bright blue eyes and a kind expression.

Her home, when she is at home, is in Glens Fall

s, New

York. There. We are settled.

The customs officials will speak English, we hope,

and leave us our bourbon and cigarettes.

Ports are necessities, like postage stamps, or soap,

but they

seldom seem to care what impression they make,

or, like this, only attempt, since it does not matter,

the unassertive colors of soap, or postage stamps—

wasting away like the former, slipping the way the latter

do when

we mail the letteres we wrote on the boat,

either because the glue here is very inferior

or because of the heat. We leave Santos at once;

we are driving to the interior.

here, after a meager diet of horizon, is some scenery;

impractically shaped and—who knows?—self-pitying mountains,

sad and harsh beneath their frivolous greenery,

some of them painted a feeble pink, or blue,

and some tall, uncertain palms. Oh, tourist,

is this how this country is going to answer you

and a better life, and complete comprehension

of both at last, and immediately,

after eighteen days of suspension?

a strange and ancient craft, flying a strange and brillant rag.

So that's the flag. I never saw it before.

I somehow never thought of there being a flag,

and paper money; they remain to be seen.

And gingerly now we climb down the ladder backward,

myself and a fellow passenger named Miss Breen,

waiting to be loaded with green coffee beans.

Please, boy, do be more careful with that boat hook!

Watch out! Oh! It has caught Miss Breen's

a retired police lieutenant, six feet tall,

with beautiful bright blue eyes and a kind expression.

Her home, when she is at home, is in Glens Fall

The customs officials will speak English, we hope,

and leave us our bourbon and cigarettes.

Ports are necessities, like postage stamps, or soap,

or, like this, only attempt, since it does not matter,

the unassertive colors of soap, or postage stamps—

wasting away like the former, slipping the way the latter

either because the glue here is very inferior

or because of the heat. We leave Santos at once;

we are driving to the interior.

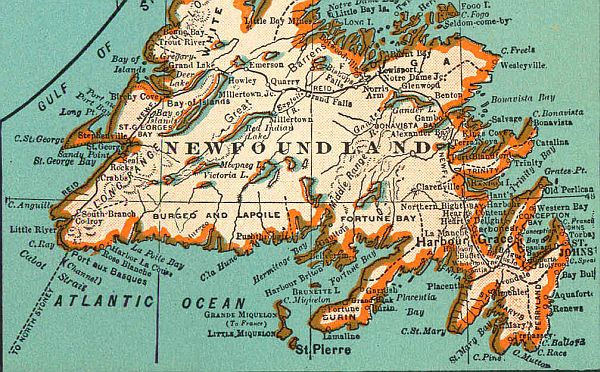

The Map

Land

lies in water; it is shadowed green.

Shadows, or are they shallows, at its edges

showing the line of long sea-weeded ledges

where weeds hang to the simple blue from green.

Or does the land lean down to lift the sea from under,

drawing it unperturbed around itself?

Along the fine tan sandy shelf

is the land tugging at the sea from under?

The shadow

of Newfoundland lies flat and still.

Labrador’s yellow, where the moony Eskimo

has oiled it. We can stroke these lovely bays,

under a glass as if they were expected to blossom,

or as if to provide a clean cage for invisible fish.

The names of seashore towns run out to sea,

the names of cities cross the neighboring mountains

-the printer here experiencing the same excitement

as when emotion too far exceeds its cause.

These peninsulas take the water between thumb and finger

like women feeling for the smoothness of yard-goods.

Mapped

waters are more quiet than the land is,

lending the land their waves’ own conformation:

and Norway’s hare runs south in agitation,

profiles investigate the sea, where land is.

Are they assigned, or can the countries pick their colors?

-What suits the character or the native waters best.

Topography displays no favorites; North’s as near as West.

More delicate than the historians’ are the map-makers’ colors.

Shadows, or are they shallows, at its edges

showing the line of long sea-weeded ledges

where weeds hang to the simple blue from green.

Or does the land lean down to lift the sea from under,

drawing it unperturbed around itself?

Along the fine tan sandy shelf

is the land tugging at the sea from under?

Labrador’s yellow, where the moony Eskimo

has oiled it. We can stroke these lovely bays,

under a glass as if they were expected to blossom,

or as if to provide a clean cage for invisible fish.

The names of seashore towns run out to sea,

the names of cities cross the neighboring mountains

-the printer here experiencing the same excitement

as when emotion too far exceeds its cause.

These peninsulas take the water between thumb and finger

like women feeling for the smoothness of yard-goods.

lending the land their waves’ own conformation:

and Norway’s hare runs south in agitation,

profiles investigate the sea, where land is.

Are they assigned, or can the countries pick their colors?

-What suits the character or the native waters best.

Topography displays no favorites; North’s as near as West.

More delicate than the historians’ are the map-makers’ colors.

The Fish

I caught

a tremendous fish

and held him beside the boat

half out of water, with my hook

fast in a corner of his mouth.

He didn't fight.

He hadn't fought at all.

He hung a grunting weight,

battered and venerable

and homely. Here and there

his brown skin hung in strips

like ancient wallpaper,

and its pattern of darker brown

was like wallpaper:

shapes like full-blown roses

stained and lost through age.

He was speckled with barnacles,

fine rosettes of lime,

and infested

with tiny white sea-lice,

and underneath two or three

rags of green weed hung down.

While his gills were breathing in

the terrible oxygen

—the frightening gills,

fresh and crisp with blood,

that can cut so badly—

I thought of the coarse white flesh

packed in like feathers,

the big bones and the little bones,

the dramatic reds and blacks

of his shiny entrails,

and the pink swim-bladder

like a big peony.

I looked into his eyes

which were far larger than mine

but shallower, and yellowed,

the irises backed and packed

with tarnished tinfoil

seen through the lenses

of old scratched isinglass.

They shifted a little, but not

to return my stare.

—It was more like the tipping

of an object toward the light.

I admired his sullen face,

the mechanism of his jaw,

and then I saw

that from his lower lip

—if you could call it a lip—

grim, wet, and weaponlike,

hung five old pieces of fish-line,

or four and a wire leader

with the swivel still attached,

with all their five big hooks

grown firmly in his mouth.

A green line, frayed at the end

where he broke it, two heavier lines,

and a fine black thread

still crimped from the strain and snap

when it broke and he got away.

Like medals with their ribbons

frayed and wavering,

a five-haired beard of wisdom

trailing from his aching jaw.

I stared and stared

and victory filled up

the little rented boat,

from the pool of bilge

where oil had spread a rainbow

around the rusted engine

to the bailer rusted orange,

the sun-cracked thwarts,

the oarlocks on their strings,

the gunnels—until everything

was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!

And I let the fish go.

and held him beside the boat

half out of water, with my hook

fast in a corner of his mouth.

He didn't fight.

He hadn't fought at all.

He hung a grunting weight,

battered and venerable

and homely. Here and there

his brown skin hung in strips

like ancient wallpaper,

and its pattern of darker brown

was like wallpaper:

shapes like full-blown roses

stained and lost through age.

He was speckled with barnacles,

fine rosettes of lime,

and infested

with tiny white sea-lice,

and underneath two or three

rags of green weed hung down.

While his gills were breathing in

the terrible oxygen

—the frightening gills,

fresh and crisp with blood,

that can cut so badly—

I thought of the coarse white flesh

packed in like feathers,

the big bones and the little bones,

the dramatic reds and blacks

of his shiny entrails,

and the pink swim-bladder

like a big peony.

I looked into his eyes

which were far larger than mine

but shallower, and yellowed,

the irises backed and packed

with tarnished tinfoil

seen through the lenses

of old scratched isinglass.

They shifted a little, but not

to return my stare.

—It was more like the tipping

of an object toward the light.

I admired his sullen face,

the mechanism of his jaw,

and then I saw

that from his lower lip

—if you could call it a lip—

grim, wet, and weaponlike,

hung five old pieces of fish-line,

or four and a wire leader

with the swivel still attached,

with all their five big hooks

grown firmly in his mouth.

A green line, frayed at the end

where he broke it, two heavier lines,

and a fine black thread

still crimped from the strain and snap

when it broke and he got away.

Like medals with their ribbons

frayed and wavering,

a five-haired beard of wisdom

trailing from his aching jaw.

I stared and stared

and victory filled up

the little rented boat,

from the pool of bilge

where oil had spread a rainbow

around the rusted engine

to the bailer rusted orange,

the sun-cracked thwarts,

the oarlocks on their strings,

the gunnels—until everything

was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!

And I let the fish go.

Cirque

D'Hiver

Across

the floor flits the mechanical toy,

fit for a king of several centuries back.

A little circus horse with real white hair.

His eyes are glossy black.

He bears a little dancer on his back.

She

stands upon her toes and turns and turns.

A slanting spray of artificial roses

is stitched across her skirt and tinsel bodice.

Above her head she poses

another spray of artificial roses.

His mane

and tail are straight from Chirico.

He has a formal, melancholy soul.

He feels her pink toes dangle toward his back

along the little pole

that pierces both her body and her soul

and goes

through his, and reappears below,

under his belly, as a big tin key.

He canters three steps, then he makes a bow,

canters again, bows on one knee,

canters, then clicks and stops, and looks at me.

The

dancer, by this time, has turned her back.

He is the more intelligent by far.

Facing each other rather desperately—

his eye is like a star—

we stare and say, "Well, we have come this far."

Chemin

De Fer

Alone on

the railroad track

I walked with pounding heart.

The ties were too close together

or maybe too far apart.

The

scenery was impoverished:

scrub-pine and oak; beyond

its mingled gray-green foliage

I saw the little pond

where

the dirty old hermit lives,

lie like an old tear

holding onto its injuries

lucidly year after year.

The

hermit shot off his shot-gun

and the tree by his cabin shook.

Over the pond went a ripple

The pet hen went chook-chook.

"Love

should be put into action!"

screamed the old hermit.

Across the pond an echo

tried and tried to confirm it.

O breath

Beneath

that loved and celebrated breast,

silent, bored really blindly veined,

grieves, maybe lives and lets

live, passes bets,

something moving but invisibly,

and with what clamor why restrained

I cannot fathom even a ripple.

(See the thin flying of nine black hairs

four around one five the other nipple,

flying almost intolerably on your own breath.)

Equivocal, but what we have in common's bound to be there,

whatever we must own equivalents for,

something that maybe I could bargain with

and make a separate peace beneath

within if never with.

fit for a king of several centuries back.

A little circus horse with real white hair.

His eyes are glossy black.

He bears a little dancer on his back.

A slanting spray of artificial roses

is stitched across her skirt and tinsel bodice.

Above her head she poses

another spray of artificial roses.

He has a formal, melancholy soul.

He feels her pink toes dangle toward his back

along the little pole

that pierces both her body and her soul

under his belly, as a big tin key.

He canters three steps, then he makes a bow,

canters again, bows on one knee,

canters, then clicks and stops, and looks at me.

He is the more intelligent by far.

Facing each other rather desperately—

his eye is like a star—

we stare and say, "Well, we have come this far."

I walked with pounding heart.

The ties were too close together

or maybe too far apart.

scrub-pine and oak; beyond

its mingled gray-green foliage

I saw the little pond

lie like an old tear

holding onto its injuries

lucidly year after year.

and the tree by his cabin shook.

Over the pond went a ripple

The pet hen went chook-chook.

screamed the old hermit.

Across the pond an echo

tried and tried to confirm it.

silent, bored really blindly veined,

grieves, maybe lives and lets

live, passes bets,

something moving but invisibly,

and with what clamor why restrained

I cannot fathom even a ripple.

(See the thin flying of nine black hairs

four around one five the other nipple,

flying almost intolerably on your own breath.)

Equivocal, but what we have in common's bound to be there,

whatever we must own equivalents for,

something that maybe I could bargain with

and make a separate peace beneath

within if never with.

At the

Fishhouses

down by one of the fishhouses

an old man sits netting,

his net, in the gloaming almost invisible,

a dark purple-brown,

and his shuttle worn and polished.

The air smells so strong of codfish

it makes one’s nose run and one’s eyes water.

The five fishhouses have steeply peaked roofs

and narrow, cleated gangplanks slant up

to storerooms in the gables

for the wheelbarrows to be pushed up and down on.

All is silver: the heavy surface of the sea,

swelling slowly as if considering spilling over,

is opaque, but the silver of the benches,

the lobster pots, and masts, scattered

among the wild jagged rocks,

is of an apparent translucence

like the small old buildings with an emerald moss

growing on their shoreward walls.

The big fish tubs are completely lined

with layers of beautiful herring scales

and the wheelbarrows are similarly plastered

with creamy iridescent coats of mail,

with small iridescent flies crawling on them.

Up on the little slope behind the houses,

set in the sparse bright sprinkle of grass,

is an ancient wooden capstan,

cracked, with two long bleached handles

and some melancholy stains, like dried blood,

where the ironwork has rusted.

The old man accepts a Lucky Strike.

He was a friend of my grandfather.

We talk of the decline in the population

and of codfish and herring

while he waits for a herring boat to come in.

There are sequins on his vest and on his thumb.

He has scraped the scales, the principal beauty,

from unnumbered fish with that black old knife,

the blade of which is almost worn away.

where they haul up the boats, up the long ramp

descending into the water, thin silver

tree trunks are laid horizontally

across the gray stones, down and down

at intervals of four or five feet.

element bearable to no mortal,

to fish and to seals . . . One seal particularly

I have seen here evening after evening.

He was curious about me. He was interested in music;

like me a believer in total immersion,

so I used to sing him Baptist hymns.

I also sang “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.”

He stood up in the water and regarded me

steadily, moving his head a little.

Then he would disappear, then suddenly emerge

almost in the same spot, with a sort of shrug

as if it were against his better judgment.

Cold dark deep and absolutely clear,

the clear gray icy water . . . Back, behind us,

the dignified tall firs begin.

Bluish, associating with their shadows,

a million Christmas trees stand

waiting for Christmas. The water seems suspended

above the rounded gray and blue-gray stones.

I have seen it over and over, the same sea, the same,

slightly, indifferently swinging above the stones,

icily free above the stones,

above the stones and then the world.

If you should dip your hand in,

your wrist would ache immediately,

your bones would begin to ache and your hand would burn

as if the water were a transmutation of fire

that feeds on stones and burns with a dark gray flame.

If you tasted it, it would first taste bitter,

then briny, then surely burn your tongue.

It is like what we imagine knowledge to be:

dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free,

drawn from the cold hard mouth

of the world, derived from the rocky breasts

forever, flowing and drawn, and since

our knowledge is historical, flowing, and flown.

The

Unbeliever

with his eyes fast closed.

The sails fall away below him

like the sheets of his bed,

leaving out in the air of the night the sleeper's head.

asleep he curled

in a gilded ball on the mast's top,

or climbed inside

a gilded bird, or blindly seated himself astride.

said a cloud. "I never move.

See the pillars there in the sea?"

Secure in introspection

he peers at the watery pillars of his reflection.

and remarked that the air

was "like marble." He said: "Up here

I tower through the sky

for the marble wings on my tower-top fly."

with his eyes closed tight.

The gull inquired into his dream,

which was, "I must not fall.

The spangled sea below wants me to fall.

It is hard as diamonds; it wants to destroy us all."

looks out a million miles

(and perhaps with pride, at herself,

but she never, never smiles)

far and away beyond sleep, or

perhaps she’s a daytime sleeper.

she’d tell it to go to hell,

and she’d find a body of water,

or a mirror, on which to dwell.

So wrap up care in a cobweb

and drop it down the well

where left is always right,

where the shadows are really the body,

where we stay awake all night,

where the heavens are shallow as the sea

is now deep, and you love me.

Manners

as we sat on the wagon seat,

“Be sure to remember to always

speak to everyone you meet.”

My grandfather’s whip tapped his hat.

“Good day, sir. Good day. A fine day.”

And I said it and bowed where I sat.

with his big pet crow on his shoulder.

“Always offer everyone a ride;

don’t forget that when you get older,”

climbed up with us, but the crow

gave a “Caw!” and flew off. I was worried.

How would he know where to go?

from fence post to fence post, ahead;

and when Willy whistled he answered.

“A fine bird,” my grandfather said,

nicely when he’s spoken to.

Man or beast, that’s good manners.

Be sure that you both always do.”

the dust hid the people’s faces,

but we shouted “Good day! Good day!

Fine day!” at the top of our voices.

he said that the mare was tired,

so we all got down and walked,

as our good manners required.

First

Death In Nova Scotia

my mother laid out Arthur

beneath the chromographs:

Edward, Prince of Wales,

with Princess Alexandra,

and King George with Queen Mary.

Below them on the table

stood a stuffed loon

shot and stuffed by Uncle

Arthur, Arthur's father.

a bullet into him,

he hadn't said a word.

He kept his own counsel

on his white, frozen lake,

the marble-topped table.

His breast was deep and white,

cold and caressable;

his eyes were red glass,

much to be desired.

"Come and say good-bye

to your little cousin Arthur."

I was lifted up and given

one lily of the valley

to put in Arthur's hand.

Arthur's coffin was

a little frosted cake,

and the red-eyed loon eyed it

from his white, frozen lake.

He was all white, like a doll

that hadn't been painted yet.

Jack Frost had started to paint him

the way he always painted

the Maple Leaf (Forever).

He had just begun on his hair,

a few red strokes, and then

Jack Frost had dropped the brush

and left him white, forever.

were warm in red and ermine;

their feet were well wrapped up

in the ladies' ermine trains.

They invited Arthur to be

the smallest page at court.

But how could Arthur go,

clutching his tiny lily,

with his eyes shut up so tight

and the roads deep in snow?

Questions

of Travel

There

are too many waterfalls here; the crowded streams

hurry too rapidly down to the sea,

hurry too rapidly down to the sea,

and the

pressure of so many clouds on the mountaintops

makes them spill over the sides in soft slow-motion,

turning to waterfalls under our very eyes.

—For if those streaks, those mile-long, shiny, tearstains,

aren't waterfalls yet,

in a quick age or so, as ages go here,

they probably will be.

But if the streams and clouds keep travelling, travelling,

the mountains look like the hulls of capsized ships,

slime-hung and barnacled.

Think of the long trip home.

Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?

Where should we be today?

Is it right to be watching strangers in a play

in this strangest of theatres?

What childishness is it that while there's a breath of life

in our bodies, we are determined to rush

to see the sun the other way around?

The tiniest green hummingbird in the world?

To stare at some inexplicable old stonework,

inexplicable and impenetrable,

at any view,

instantly seen and always, always delightful?

Oh, must we dream our dreams

and have them, too?

And have we room

for one more folded sunset, still quite warm?

But surely it would have been a pity

not to have seen the trees along this road,

really exaggerated in their beauty,

not to have seen them gesturing

like noble pantomimists, robed in pink.

—Not to have had to stop for gas and heard

the sad, two-noted, wooden tune

of disparate wooden clogs

carelessly clacking over

a grease-stained filling-station floor.

(In another country the clogs would all be tested.

Each pair there would have identical pitch.)

—A pity not to have heard

the other, less primitive music of the fat brown bird

who sings above the broken gasoline pump

in a bamboo church of Jesuit baroque:

three towers, five silver crosses.

—Yes, a pity not to have pondered,

blurr'dly and inconclusively,

on what connection can exist for centuries

between the crudest wooden footwear

and, careful and finicky,

the whittled fantasies of wooden footwear

and, careful and finicky,

the whittled fantasies of wooden cages.

—Never to have studied history in

the weak calligraphy of songbirds' cages.

—And never to have had to listen to rain

so much like politicians' speeches:

two hours of unrelenting oratory

and then a sudden golden silence

in which the traveller takes a notebook, writes:

"Is it lack of imagination that makes us come

to imagined places, not just stay at home?

Or could Pascal have been not entirely right

about just sitting quietly in one's room?

Continent, city, country, society:

the choice is never wide and never free.

And here, or there . . . No. Should we have stayed at home,

wherever that may be?"

makes them spill over the sides in soft slow-motion,

turning to waterfalls under our very eyes.

—For if those streaks, those mile-long, shiny, tearstains,

aren't waterfalls yet,

in a quick age or so, as ages go here,

they probably will be.

But if the streams and clouds keep travelling, travelling,

the mountains look like the hulls of capsized ships,

slime-hung and barnacled.

Think of the long trip home.

Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?

Where should we be today?

Is it right to be watching strangers in a play

in this strangest of theatres?

What childishness is it that while there's a breath of life

in our bodies, we are determined to rush

to see the sun the other way around?

The tiniest green hummingbird in the world?

To stare at some inexplicable old stonework,

inexplicable and impenetrable,

at any view,

instantly seen and always, always delightful?

Oh, must we dream our dreams

and have them, too?

And have we room

for one more folded sunset, still quite warm?

But surely it would have been a pity

not to have seen the trees along this road,

really exaggerated in their beauty,

not to have seen them gesturing

like noble pantomimists, robed in pink.

—Not to have had to stop for gas and heard

the sad, two-noted, wooden tune

of disparate wooden clogs

carelessly clacking over

a grease-stained filling-station floor.

(In another country the clogs would all be tested.

Each pair there would have identical pitch.)

—A pity not to have heard

the other, less primitive music of the fat brown bird

who sings above the broken gasoline pump

in a bamboo church of Jesuit baroque:

three towers, five silver crosses.

—Yes, a pity not to have pondered,

blurr'dly and inconclusively,

on what connection can exist for centuries

between the crudest wooden footwear

and, careful and finicky,

the whittled fantasies of wooden footwear

and, careful and finicky,

the whittled fantasies of wooden cages.

—Never to have studied history in

the weak calligraphy of songbirds' cages.

—And never to have had to listen to rain

so much like politicians' speeches:

two hours of unrelenting oratory

and then a sudden golden silence

in which the traveller takes a notebook, writes:

"Is it lack of imagination that makes us come

to imagined places, not just stay at home?

Or could Pascal have been not entirely right

about just sitting quietly in one's room?

Continent, city, country, society:

the choice is never wide and never free.

And here, or there . . . No. Should we have stayed at home,

wherever that may be?"

The Imaginary Iceberg

We'd

rather have the iceberg than the ship,

although it meant the end of travel.

Although it stood stock-still like cloudy rock

and all the sea were moving marble.

We'd rather have the iceberg than the ship;

we'd rather own this breathing plain of snow

though the ship's sails were laid upon the sea

as the snow lies undissolved upon the water.

O solemn, floating field,

are you aware an iceberg takes repose

with you, and when it wakes may pasture on your snows?

This is

a scene a sailor'd give his eyes for.

The ship's ignored. The iceberg rises

and sinks again; its glassy pinnacles

correct elliptics in the sky.

This is a scene where he who treads the boards

is artlessly rhetorical. The curtain

is light enough to rise on finest ropes

that airy twists of snow provide.

The wits of these white peaks

spar with the sun. Its weight the iceberg dares

upon a shifting stage and stands and stares.

The

iceberg cuts its facets from within.

Like jewelry from a grave

it saves itself perpetually and adorns

only itself, perhaps the snows

which so surprise us lying on the sea.

Good-bye, we say, good-bye, the ship steers off

where waves give in to one another's waves

and clouds run in a warmer sky.

Icebergs behoove the soul

(both being self-made from elements least visible)

to see them so: fleshed, fair, erected indivisible.

although it meant the end of travel.

Although it stood stock-still like cloudy rock

and all the sea were moving marble.

We'd rather have the iceberg than the ship;

we'd rather own this breathing plain of snow

though the ship's sails were laid upon the sea

as the snow lies undissolved upon the water.

O solemn, floating field,

are you aware an iceberg takes repose

with you, and when it wakes may pasture on your snows?

The ship's ignored. The iceberg rises

and sinks again; its glassy pinnacles

correct elliptics in the sky.

This is a scene where he who treads the boards

is artlessly rhetorical. The curtain

is light enough to rise on finest ropes

that airy twists of snow provide.

The wits of these white peaks

spar with the sun. Its weight the iceberg dares

upon a shifting stage and stands and stares.

Like jewelry from a grave

it saves itself perpetually and adorns

only itself, perhaps the snows

which so surprise us lying on the sea.

Good-bye, we say, good-bye, the ship steers off

where waves give in to one another's waves

and clouds run in a warmer sky.

Icebergs behoove the soul

(both being self-made from elements least visible)

to see them so: fleshed, fair, erected indivisible.

Brazil,

January 1, 1502

. . . embroidered nature . . . tapestried landscape.

––Landscape Into Art, by Sir Kenneth Clark

Januaries, Nature greets our eyes

exactly as she must have greeted theirs:

every square inch filling in with foliage––

big leaves, little leaves, and giant leaves,

blue, blue-green, and olive,

with occasional lighter veins and edges,

or a satin underleaf turned over;

monster ferns

in silver-gray relief,

and flowers, too, like giant water lilies

up in the air––up, rather, in the leaves––

purple, yellow, two yellows, pink,

rust red and greenish white;

solid but airy; fresh as if just finished

and taken off the frame.

A blue-white sky, a simple web,

backing for feathery detail:

brief arcs, a pale-green broken wheel,

a few palms, swarthy, squat, but delicate;

and perching there in profile, beaks agape,

the big symbolic birds keep quiet,

each showing only half his puffed and padded,

pure-colored or spotted breast.

Still in the foreground there is Sin:

five sooty dragons near some massy rocks.

The rocks are worked with lichens, gray moonbursts

splattered and overlapping,

threatened from underneath by moss

in lovely hell-green flames,

attacked above

by scaling-ladder vines, oblique and near,

“one leaf yes and one leaf no” (in Portuguese).

The lizards scarcely breathe; all eyes

are on the small, female one, back-to,

her wicked tail straight up and over,

red as a red-hot wire.

Just so the Christians, hard as nails,

tiny as nails, glinting,

in creaking armor, came and found it all,

not unfamiliar:

no lovers’ walks, no bowers,

no cherries to be picked, no lute music,

but corresponding, nevertheless,

to an old dream of wealth and luxury

already out of style when they left home––

wealth, plus a brand-new pleasure.

Directly after Mass, humming perhaps

L’Homme armé or some such tune,

each out to catch an Indian for himself––

those maddening little women who kept calling,

calling to each other (or had the birds waked up?)

and retreating, always retreating, behind it.

. . . embroidered nature . . . tapestried landscape.

––Landscape Into Art, by Sir Kenneth Clark

Januaries, Nature greets our eyes

exactly as she must have greeted theirs:

every square inch filling in with foliage––

big leaves, little leaves, and giant leaves,

blue, blue-green, and olive,

with occasional lighter veins and edges,

or a satin underleaf turned over;

monster ferns

in silver-gray relief,

and flowers, too, like giant water lilies

up in the air––up, rather, in the leaves––

purple, yellow, two yellows, pink,

rust red and greenish white;

solid but airy; fresh as if just finished

and taken off the frame.

A blue-white sky, a simple web,

backing for feathery detail:

brief arcs, a pale-green broken wheel,

a few palms, swarthy, squat, but delicate;

and perching there in profile, beaks agape,

the big symbolic birds keep quiet,

each showing only half his puffed and padded,

pure-colored or spotted breast.

Still in the foreground there is Sin:

five sooty dragons near some massy rocks.

The rocks are worked with lichens, gray moonbursts

splattered and overlapping,

threatened from underneath by moss

in lovely hell-green flames,

attacked above

by scaling-ladder vines, oblique and near,

“one leaf yes and one leaf no” (in Portuguese).

The lizards scarcely breathe; all eyes

are on the small, female one, back-to,

her wicked tail straight up and over,

red as a red-hot wire.

Just so the Christians, hard as nails,

tiny as nails, glinting,

in creaking armor, came and found it all,

not unfamiliar:

no lovers’ walks, no bowers,

no cherries to be picked, no lute music,

but corresponding, nevertheless,

to an old dream of wealth and luxury

already out of style when they left home––

wealth, plus a brand-new pleasure.

Directly after Mass, humming perhaps

L’Homme armé or some such tune,

each out to catch an Indian for himself––

those maddening little women who kept calling,

calling to each other (or had the birds waked up?)

and retreating, always retreating, behind it.

Breakfast

Song

My love, my saving grace,

your eyes are awfully blue.

I kiss your funny face,

your coffee-flavored mouth.

Last night I slept with you.

Today I love you so

how can I bear to go

(as soon I must, I know)

to bed with ugly death

in that cold, filthy place,

to sleep there without you,

without the easy breath

and nightlong, limblong warmth

I've grown accustomed to?

—Nobody wants to die;

tell me it is a lie!

But no, I know it's true.

It's just the common case;

there's nothing one can do.

My love, my saving grace,

your eyes are awfully blue

early and instant blue.

My love, my saving grace,

your eyes are awfully blue.

I kiss your funny face,

your coffee-flavored mouth.

Last night I slept with you.

Today I love you so

how can I bear to go

(as soon I must, I know)

to bed with ugly death

in that cold, filthy place,

to sleep there without you,

without the easy breath

and nightlong, limblong warmth

I've grown accustomed to?

—Nobody wants to die;

tell me it is a lie!

But no, I know it's true.

It's just the common case;

there's nothing one can do.

My love, my saving grace,

your eyes are awfully blue

early and instant blue.

Late Air

From a magician’s midnight sleeve

the radio-singers

distribute all their love-songs

over the dew-wet lawns.

And like a fortune-teller’s

their marrow-piercing guesses are whatever you believe.

But on the Navy Yard aerial I find

better witnesses

for love on summer nights.

Five remote lights

keep their nests there; Phoenixes

burn quietly, where the dew cannot climb.

From a magician’s midnight sleeve

the radio-singers

distribute all their love-songs

over the dew-wet lawns.

And like a fortune-teller’s

their marrow-piercing guesses are whatever you believe.

But on the Navy Yard aerial I find

better witnesses

for love on summer nights.

Five remote lights

keep their nests there; Phoenixes

burn quietly, where the dew cannot climb.

More

poems here :

Some articles of interest

Hiding

in Plain Sight : The loneliness of

Elizabeth Bishop. By David Yaffe. The Nation , October 19, 2017

“Familiar,

Unbidden”: Finding Home with Elizabeth Bishop. By Elisa Wouk Almino. Hyperallergic ,

November

8, 2015

A tale

of two poets, Thom Gunn and Elizabeth Bishop. By Colm Tóibín. The Guardian,

April 11, 2015.

Elizabeth

Bishop, paintings

Elizabeth Bishop: Exchanging Hats – in pictures. By William Benton. The Guardian, November 3, 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment