In my

freshman year at Queens College, I had a strange awakening—strange in that the

attendant, overmastering emotion was a combination of humiliation and pleasure.

My English professor had called me to his desk and handed me the A+ paper I had

written on Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia and suggested that I make an

appointment to see him. This was no ordinary suggestion at the City University

of New York, where professors never scheduled regular office hours and only

rarely invited students to private conferences.

I was

uneasy about the meeting, though I imagined that Professor Stone wished simply

to congratulate me further, perhaps even to recommend that I join the staff of

the college literary magazine, or to enlist my assistance as a tutor. Delusions

of grandeur. Modest grandeur.

Professor

Stone’s office had been carved out of a warren of rooms in the fourth-floor

attic of the English Department building, where I was greeted with a warm

handshake and a “delighted you could come.” Though the encounter took place

almost 60 years ago, I remember everything about it—the few books scattered on

a small wooden table, the neatly combed silver hair on the professor’s head,

his amiable, ironic eyes. Most clearly I remember the surprising moment when

another professor named Magalaner was called in and stood next to Professor

Stone, both men smiling and looming ominously over me. It was then that I was

asked to describe—in a few sentences, or more, don’t hesitate—the paper I’d

written on Orwell.

Which of

course I did, picking up steam after the first few sentences of diffident

preamble, until Professor Stone asked me to stop, that’s quite enough, and then

turned to his colleague with the words “see what I mean?” and Magalaner

assented. The two men only now pulled over two chairs and sat down, close

enough that our knees almost touched, and seemed to look me over, as if taking

my measure. Both of them were smiling, so that again I speculated that I was to

be offered a prize, a summer job, or who knew what else.

“I’ve a

feeling,” Professor Stone said, “that you may be the first person in your

family to go to college.”

“It’s

true,” I replied.

“You

write very well,” he offered.

“Very

well,” said Magalaner, who had apparently also read my paper.

“But you

know,” Stone went on, edging his chair just a bit closer to mine, “I didn’t

call you here to congratulate you, but to tell you something you need to hear,

and of course I trust that you’ll listen carefully—with Professor Magalaner

here to back me up—when I tell you, very plainly, that though you are a bright

and gifted young fellow, your speech, I mean the sounds you make when you

speak, are such that no one will ever take you seriously. I repeat, no one will

ever take you seriously, if you don’t at once do something about this. Do you

understand me?”

I’ve

told this story over the years, starting on that very first night with my

teenage sister, explaining what I understood: namely, that a man I admired, who

had reason to admire me, thought that when I opened my mouth I sounded like

someone by no means admirable. It was easy to accept that no one close to me

would have mentioned this before, given that, presumably, we all shared this

grave disability, and failed to think it a disability at all. Professor Stone

didn’t sound like anyone in our family, we may have thought, simply because,

after all, he was an educated man and was not supposed to sound or think like

us.

In any

event, my teacher moved at once to extract from me a promise that I would

enroll in remedial speech courses for as long as I was in college, and not “so

much as consider giving them up, not even if you find them tedious.” The

proposal left me feeling oddly consoled, if also somewhat ashamed. Consoled by

the thought that there might be a cure for my coarse Brooklynese, as my teacher

referred to it, and that the prescription was indisputably necessary. Unsure

whether to thank my interlocutors or just stand up and slink ignominiously

away, I agreed to enroll immediately in one of those speech courses, ending the

meeting with an awkward, “Is that all?”

A former

student, hearing my story a few years ago at our dinner table, after telling

her own tale of a recent humiliation, asked, “Who the fuck did that guy think

he was?” and added that he was “lucky you didn’t just kick his teeth out.” She

was concerned, clearly, that even after so many years, my sense of self might

still be at risk, the injury still alive within me. And yet, though I’ve often

played out the whole encounter in my head, I had decided within hours of my

escape that I had been offered a gift. An insult as well, to be sure, but

delivered not with an intention to hurt but to save and uplift. It would have been

easy to be offended by the attempt to impress upon someone so young the idea

that he would undoubtedly want to become the sort of person whose class origins

would henceforth be undetectable. But I had not been programmed to be offended,

and was, in my innocent way, ambitious to be taken seriously, and though I

rapidly came to loathe the speech exercises to which I was soon subjected, I

thought it my duty and my privilege to be subjected to them. Night after night,

standing before the mirror in my parents’ bathroom, I shaped the sounds I was

taught to shape, and I imagined that one day Professor Stone would beam with

satisfaction at the impeccably beautiful grace notes I would produce.

A long

story, perhaps, for opening an essay on privilege. But the idea of privilege

has moved many people to say things both nonsensical and appalling, and it is

worth pointing out what is often ignored or willfully obscured: that privilege

is by no means easy to describe or understand. Say, if you like, that privilege

is an advantage, earned or unearned, and you will be apt to ask several

important questions. Earned according to whom? Unearned signifying shameful or

immoral? The advantage to be renounced or held onto? To what end? Whose?

Privilege, the name of an endowment without which we would all be miraculously

released from what exactly? Is there evidence, anywhere, that the attention

directed at privilege in recent years has resulted in a reduction in inequality

or a more generous public discourse? Say privilege and you may well believe you

have said something meaningful, leveled a resounding charge, when perhaps you

have not begun to think about what is entailed in so loaded a term. What may

once have been an elementary descriptor—“he has the privilege of studying the violin

with a first-rate music instructor”—is at present promiscuously and often

punitively deployed to imply a wide range of advantages or deficits against

which no one can be adequately defended.

Is

privilege at the root of the story I have told about my freshman-year

adventure? Consider that Professor Stone was himself the beneficiary of the

privilege, so-called, that allowed him to deliver a potentially devastating

message to a boy he barely knew, and with little fear of contradiction. The

protocols lately associated with what the writer Phoebe Maltz Bovy, author of

The Perils of “Privilege,” calls the “privilege turn” in contemporary culture

would demand that the professor acknowledge his privilege and proceed with

greater sensitivity to the feelings of his student. If he had been challenged

at the time, the professor would have noted that his action reflected his

concern for his student, and he would not have felt that any special privilege

had been involved in the exercise of his authority. That our positions were

unequal would have seemed to him natural but in no way problematic—in the very

nature of the teacher-student relationship—reflecting, moreover, only a

temporary arrangement, requiring of me no permanent resignation to my fate as a

subordinate, consigned for all time to yield to the whims of a master.

In

short, the very notion of privilege in his case would have seemed to him—quite

as it seems to me now—of little or no importance. Of course, if I were so

inclined, I might now level the charge at my teacher, retroactively, as it

were. After all, inequality is today often regarded as unjust or intolerable,

even criminal, even though in most situations we have no particular reason to

feel aggrieved. During a brief period when I saw a psychotherapist, I noted the

inequality built into our situation. I know nothing at all about the emotions

of my palely imperturbable therapist, I thought, whereas he is forever asking

me personal questions and drawing astounding conclusions about my so-called

motives. Our ritual meetings were designed to make me feel that our relations

were anything but reciprocal, and he had the privilege of treating everything I

said as suspect, or symptomatic, whereas I was required to treat the few things

he said as mature and reliable. The inequality was built into the situation,

and there was nothing for me to do but nurture my resentment or accept that I

enjoyed the very different privilege of placing myself in the hands of someone

who might help me.

Privilege,

then, like inequality, is not usually a simple matter. Not in the past, not at

present, not even in the domain of male privilege, with all that particular

species of entitlement and inequality entails. I suppose it fair to say that I

know as much, and as little, about my own exercise of male privilege as most

men who have enjoyed its benefits without sufficiently acknowledging them. But

I suppose, as well, what it is also fair to say: namely, that the exercise of

privilege among men is no unitary thing. My own working-class father had the

privilege, after all, of working, through the best years of his adult life, in

a Brooklyn dry goods store for six days each week, from 8 A.M. to 9 P.M., 50

weeks each year. Would he have agreed, if alerted to the fact, that he was also

the beneficiary of male privilege? I like to think that I could have persuaded

him to accept that this was so, much though the two of us would have gone on to

reflect that his “advantage,” in that respect as in many others, was almost

comically limited.

Certainly it is not a simple matter to speak

of privilege in the domain of race relations. A few years ago, I found myself

embroiled in an argument at a symposium, where one speaker had referred to

“white privilege” as a self-evident phenomenon. Was it really necessary, I

asked, to point out that there is privilege and privilege, whiteness and

whiteness? If my white colleague felt that she had a great deal to apologize

for, and thought a public symposium a suitable occasion for a display of soul

searching, that was well and good, so long as she did not also suggest that we

must all follow her lead and all feel about our own so-called privilege exactly

what she felt. Was it reasonable to suppose that whiteness confers, on everyone

who claims it, comparable experiences and privileges? Was my own background as

a working-class Jewish boy, growing up in a predominantly black community,

remotely similar to the background or disposition of a white colleague who had

never known privation, or had no contact at all with black children? Did it

matter, thinking of ourselves simply as possessors of white privilege, that one

of us had written extensively on race while the other had devoted herself to

scholarly research on metaphysical poetry? Was it not the case, I asked, that

what Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda call in The Racial Imaginary “the

boundaries” of our “imaginative sympathy” had been drawn in drastically

different ways? How could whiteness, or blackness, signify to us the same

things?

To

consider either of us primarily as white people, deliberately consigning to

irrelevance everything that made us different from each other—and different

from the kinds of white people who regard their whiteness as an endowment to be

proud of—was to deny what was clearly most important about each of us. Rankine

and Loffreda rightly challenge those who “argue that the imagination is or can

be somehow free of race,” and they mock white writers “who make a prize of

transcendence,” supposing that the imagination can be “ahistorical” or “postracial.”

But to insist that elementary distinctions be made, as between one experience

of race and another, would seem indispensable to a serious discussion of

privilege.

Though

whiteness was not an active or obvious factor in my encounter with Professor

Stone, it is possible that, had I been a black student in his class, he might

have resisted the impulse to call me in and inform me, in effect, that my

speech seemed to him low or disreputable. In this sense, the fact of my

whiteness would have conferred upon me the inestimable advantage of having been

chosen for the insult he directed at me. A peculiar advantage, to be sure. When

I told my story to a half-dozen student assistants recently, the two black

students at our dinner table showered me with sympathy and asserted that they

would have found the professor’s admonition offensive and perhaps “done

something about it.” Though I attempted then to explain my own sense of the

privilege afforded me, my students were by no means persuaded, and the white students

were sure only that things are different now, that today “respect” would

happily ensure that no professor would dare to do what my teacher had done.

A good

many of my students, white and black, are in thrall to the idea that they are

required to portray themselves as beautiful souls. Even those with little

feeling for polemic or posturing are ever at the ready to declare—like their

academic instructors—their good conscience and their attachment to the

indisputably correct virtues. Thus they find in the idea of privilege an ideal

vehicle. It seems at least to provide, to anyone who climbs on board, an

opportunity to arrive at a sort of moral high ground that costs nothing. The

students at our table were at one in feeling superior to my old teacher. He

had, they felt, been oblivious to his privilege, and they were secure in their

conviction that they would never be as oblivious as that. Their comfort lay in

their unambivalent commitment to a species of one-upmanship. Theirs was the

empty affirmation of an ideal they had no need to articulate with any

precision, but which amounted to the certainty that, above all things, we are

required to be and to remain perfectly guiltless. Nor did they recognize—not so

that I could tell—that their immurement in good conscience was itself a

privilege that could only be secured by finding others guilty, in one degree or

another, of privilege.

During a

panel discussion on political fiction convened at the New York State Summer

Writers Institute two years ago, a graduate student in the audience said that

she associated works in this genre mainly with male writers. In response, I

suggested that much of the best political fiction was in fact written by women,

and I named Doris Lessing, Nadine Gordimer, Ingeborg Bachmann, Pat Barker,

Anita Desai, Joyce Carol Oates, and others about whom I had written in books

and essays. At that, another graduate student raised her hand and, quivering

with indignation, asked me whether I was aware of the privilege I had exercised

in addressing the question. Privilege in what sense exactly? I asked. Your

authority, she said, your presumption, the sense of entitlement that permits

you to feel that you can pronounce on any question put to you. Not any

question, I said. Only a question about which I actually have something

potentially useful to say. But then of course, I added, I want, like you, to be

alert to my own power, when I have any, and to be able to acknowledge that each

of us, in a civilized setting like this one, is the beneficiary of several

different kinds of privilege.

Though

no further fireworks then erupted, it was clear to pretty much everyone present

on that occasion that privilege had been invoked as a noise word intended to

distract all of us from the substance of our discussion, and from the somehow

unpleasant spectacle of a male writer intoning the names of great women

writers, as if this were, in itself, a flagrant violation of a protocol. More,

the invoking of privilege was oddly intended to punish the speaker of the

offending words—my words—by making him into a representative of something he

could not possibly defend himself against.

Privilege,

then, is increasingly hauled in as a weapon, though wielded, in the main, by

persons attached still to the conviction that, whatever their own bristling

incivility and the punishing quietus they clearly intend to deliver, they

remain in full possession of their virtue. Can those who come on as

investigating magistrates really hope to regard themselves as generous and

tolerant people? The privilege turn has made the examining magistrate role

enticing to large numbers of those whose being-in-the-right is to them an

article of faith.

In a

recent interview, the novelist and essayist Zadie Smith speaks of her

friendship with the writer Darryl Pinckney, describing him as “a model of …

active ambivalence. He is as well read on African-American issues as anyone

could imagine being,” she goes on, and he “is absolutely aware that there is

such a thing as having been subjected to the experience of blackness, which

causes all kinds of consequences.” Even so, “and at the same time, he claims

the freedom of just being Darryl, in all his extreme particularity. I haven’t

met many people like that.”

No need

to observe—though I will—that the words “he claims the freedom of just being

Darryl” denotes the exercise of a privilege to which others would likewise hope

to stake a claim, or that Smith is right to note that not many are now equipped

to be “like that.” There is privilege, of course, in the refusal to accede to

someone else’s view of you, the refusal to emit the affirming noises that

declare unequivocally your willingness to be what others take you to be and

insist that you remain. It is not at all surprising that Smith has often

described what she calls the “cartoon thinness” of many of the identity images

we employ to certify who we are, or that a character in her recent novel Swing

Time calls upon his friend to reevaluate her sense of reality with the words

“you think far too much about race—did anyone ever tell you this?” Pinckney—in

spite of the great opening line of his novel High Cotton (“No one sat me down

and told me I was a Negro”)—has devoted virtually all of his writing to the

study of race, and yet he has refused to think of himself principally in terms

of race. Though he is “absolutely aware,” as Smith says, that race has marked

him, his brave determination has been to affirm his “extreme particularity.”

Black

writers who have challenged the standard racialist orthodoxies about color have

often come in for withering criticism from other black intellectuals. When

Ralph Ellison complained that black writers “fear to leave the uneasy sanctuary

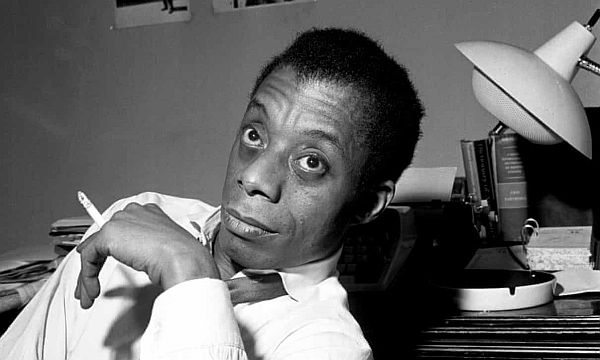

of race,” he generated a firestorm of hostility. Even James Baldwin received

considerable criticism, much of it having to do with his efforts to have it

both ways—that is, to insist upon his estrangement from the “white centuries”

of Western culture while refusing to pretend that those centuries did not shape

and define him. Baldwin famously wrote,

‘’I know, in any case, that the most crucial

time in my own development came when I was forced to recognize that I was a

kind of bastard of the West; when I followed the line of my past I did not find

myself in Europe but in Africa … I brought to Shakespeare, Bach, Rembrandt … a

special attitude. These were not really my creations, they did not contain my

history … At the same time I had no other heritage which I could possibly hope

to use—I had certainly been unfitted for the jungle or the tribe. I would have

to appropriate these white centuries, I would have to make them mine.’’

Baldwin

wears his ambivalences and refusals with the cunning of a man who is ever in

search of what will suit him. He accords to himself, as he should, the

privilege of fashioning what he calls a “special attitude,” a “special place.”

Baldwin knew that he could not be the man he wished to be, or write the books he

had to write, unless he found a personal way to declare “appropriate”

affinities. He could not operate from a doctrinaire idea of ethnic solidarity

and thus was bound to provoke disappointment in quarters where solidarity was

regarded as an indispensable virtue.

It’s

tempting to say of Baldwin that he was, after all, a great writer, and that he

was therefore singular in ways we ought not to claim for ourselves. But the

drama he enacted, rooted in his own extreme particularity, is not so very alien

to the condition to which most of us aspire, however limited our courage and

our gifts. Rankine and Loffreda note that “we wish”—all of us—to “unsettle the

assumption that it is easy or simple to write what one ‘is.’ ” But then, they

say, when we “keep familiar things familiar,” we inevitably miss what is most

important about ourselves. Baldwin’s “special attitude” required that he

repudiate familiar assumptions about what did and did not define him, and he

accorded to himself the privilege of appropriating what he needed.

Baldwin thought of the special place he was required to make for himself in terms peculiar to him and his situation. And why not? Yet, when I read the words “these were not really my creations,” I find it impossible not to think that they apply as well to me, growing up in an inner-city apartment without books or other cultural artifacts. I note too that the words—Baldwin’s words—“I might search in them in vain forever for any reflection of myself,” are somewhat misleading, in that, like myself, he would early discover reflections of himself even in works far removed from his own family setting.

But what

burns through every page of Baldwin’s writing is the truth of his own intense

subjectivity and his contempt for provincial slogans and categories, provincial

a word notably absent from discussions of privilege, which rely upon an

impoverished idea of identity and, by extension, of what rightly belongs to

each of us. The charge of privilege, as leveled even in ostensibly

sophisticated critiques, carries with it the presumption that people are

readily intelligible, their natures and motives determined by accidents of

color or class. When I read sentences that begin with the words “white persons

think” or “whites can only know,” I feel at once the fatal absence of any

intimation of radical uncertainty. The agitation we want to feel in confronting

others—or in confronting what is opaque or impenetrable in ourselves—is denied,

banished by the impulse to define and diminish by resorting to accusations of privilege—as

if the work of understanding might thereby be accomplished.

Does

privilege exist? Of course it does. Only a fool would deny that advantage is

real and that some people have what others lack. Though advantage is unevenly

distributed in any population, or within any racial or ethnic group, it is

legitimate to assert that whiteness—like maleness—has long been an advantage,

however little some wish to acknowledge it. Just so, other kinds of privilege

often determine, unfairly, the way people live, and suffer, or thrive. But then

these are commonplaces, and if not everyone is as yet prepared to accept them,

that is hardly a good reason to employ privilege in the way it has lately been

used. The culture of grievance that has taken shape in recent years has led to

what Phoebe Maltz Bovy calls “the fetishization of powerlessness” and the not

always “polite bigotry” that makes it acceptable to target groups or persons

not because of what they have done but because of what they are.

The most

promising feature of the privilege turn was its focus not on the kinds of

privilege everyone can see for themselves—expensive private schools, 10-bedroom

vacation homes, inordinate tax breaks or deductions available only to the

wealthy—but instead on advantages unacknowledged and pernicious. For a while it

seemed a good idea to dwell upon the hypocrisies that allowed us to proceed as

if class inequities were not major factors in the system that supported our

habits and assumptions. We were moved to learn things we wanted somehow not to

learn: that housing laws designed to help returning GIs discriminated against

black veterans; that college admissions boards, even where inclined to

diversify their student bodies, continued to rely upon protocols that would

ensure acceptance mainly for the wealthy or the otherwise privileged; that

apparently trivial slights or insults might conceivably affect people in

disastrous ways, while allowing those responsible for the insults to proceed as

if nothing consequential had transpired. Rankine and Loffreda argue that

“whiteness has veiled from them their own power to wound,” and though what they

call the “recourse to innocence: I did not mean to do any harm” has rightly

been called out within the framework of “privilege,” it is surely legitimate to

ask where this initially promising thrust has taken us.

For one

thing, it has taken us to the domain of cliché and pure assertion. Nothing is

easier than to wield the charge of privilege and thereby to win instant

approval, nothing easier than to beat oneself up now and then for enjoying

privilege while pretending to solidarity with the disadvantaged. There is

comedy in the rush of the well-heeled and enlightened to affirm their virtue by

signaling their guilt and their difference from those who have not yet mastered

the rituals of self-disparagement and privilege bashing required of them. And

there is temptation, surely, in the prospect of constructing a privilege-free

profile: in my case, for example, by citing my own less-than-exalted childhood

in Bedford-Stuyvesant, my struggles in three years of remedial speech courses,

not to mention the fact that I could never have succeeded in life by virtue of

good looks or an impressively masculine baritone voice. Thus, competitively

speaking, in the precinct shaped by the privilege obsession, here I stand,

nearly virtuous, though white, to be sure, and though not completely powerless,

near enough to having been so to qualify for a modicum of sympathy.

The

absurdity inherent in all of this should not obscure the damage it has wrought:

damage in sowing confusion even about the obvious—about the difference between

what is important and less important, between doing what is injurious and being

deficient in doing what is positively good, between sponsoring injustice and

simply living more or less modestly in an imperfect world. To be unable to make

these kinds of elementary distinctions is to be radically impaired, and there

seems to me no question that the tendency to invoke privilege has exacerbated

that impairment. There was, at the heart of the privilege turn, an aspiration

to enlightenment. But the partisans committed to promoting the privilege

critique are mainly interested in drawing hard lines separating the guilty from

the saved, the serenely oblivious from the righteous, fiercely aggrieved, and

censorious.

It is

hard not to see in all of this the operation of garden-variety envy, though the

online diatribes denouncing the guilty are necessarily loath to mention that

sentiment, even where it is impossible to miss. At my own college, younger

faculty members have complained publicly about the “privilege” exhibited by

colleagues who speak at length and “with confidence” about controversial

matters. The charge carries with it the wish, sometimes the suggestion, that

those “other” faculty members find a way to be ashamed of this privilege, which

so many of their colleagues do not enjoy. Thus forthrightness and

self-assurance can be made to seem as offensive and illegitimate as the Bentley

parked ostentatiously in a well-tended driveway. Again, the rage to call out

privilege is often an expression of a simple desire to have what others have,

or to cast aspersions on those who have it. It is not at all surprising that

the most brilliant and accomplished of my colleagues should lately have

inspired criticism that cites her “relentless articulacy” and her “always

having something to say.”

One

consequence of the obsession with privilege is the growing divide within

communities otherwise united by shared principles. The emphasis upon so-called

microaggressions—that is, upon what Rankine calls “slippages,” including the

failure to acknowledge privilege—has created a climate in which many people

have withdrawn from active participation in public or political life. Many

faculty members at my college have intimated, or declared, that they will no

longer become involved in controversial debates or speak on the floor at

faculty meetings. Why get involved in efforts to raise consciousness among

students by enlisting in voter registration campaigns when some students will

likely accuse you of exploiting your power and your privilege? Why join your

local Democratic Party and work to field a slate of electable candidates in a swing

district when you are apt to be pilloried for the privilege entailed in

championing moderation and electability? After all, only someone privileged

enough (and clueless enough) to embrace a gradualist approach to politics would

counsel incrementalism. Better to stay out of politics entirely, with the

privilege charge always apt to erupt and make you feel guilty.

For that

matter, why attempt to find common ground in situations where envy for your

good fortune and resentment of your advantages are sure to make everything you

do an expression of your “identity”? For all of the intensity unleashed by

proponents of the privilege critique, they would seem to have little interest

in real politics—that is, in coalition building and respect for difference. The

tendency to think of potential allies as inevitably tainted by the habits and

perspectives of their racial, ethnic, or gender cohort is unlikely to issue in

an effectual politics. The privilege turn is part of a new fundamentalism built

on a willful refusal to accept that the most obvious features of our so-called

identity are the least reliable indicators of what may reasonably be expected

of us.

None of

this is to suggest that identity, as usually conceived, counts for nothing at

all. “I am born,” writes the Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, “with a

past, and to try to cut myself off from that past … is to deform my present

relationships.” At the same time, he goes on, “rebellion against my identity is

always one possible mode of expressing it.” We are always, as it were, “moving

forward” from the condition and the tradition we inherit. A culture is in good

order only when its people are engaged in conducting a continual argument about

the assorted virtues—MacIntyre calls them “goods”—they hope to pursue. The

fundamentalism central to the privilege turn is predicated upon the assumption

of deficits inherent in groups and persons who are condemned to reflect those

deficits and to apologize, however inadequately, for embodying them. That

assumption is not only ungenerous. It is also simply untrue, given that

rebellion against aspects of identity is a feature of ordinary cultural

evolution. The envy and resentment that would deny to Pinckney his

particularity, or to Baldwin his wayward appropriation, or to W. E. B. Du Bois

his will to “summon Aristotle and Aurelius and what soul I will” are no less

vicious than promiscuous assertions of privilege deployed to deny the complex

particularity of others. Proponents of the privilege turn have adopted a sanctimonious

rhetoric to create an “us” an a “them” that answers not at all to the reality

of our common life.

The

Privilege Predicament. By Robert Boyers. The American Scholar , March 5, 2018

The

American culture war continues apace, with increasingly high stakes, between

the right and left. But over the past several years, especially online and in

academia, a parallel conflict has been taking place between liberals and

progressives. Robert Boyers, the editor of the literary journal Salmagundi and

a professor of English at Skidmore College, fits neatly, although not

reflexively, within the liberal camp. In his new book, “The Tyranny of Virtue:

Identity, the Academy, and the Hunt For Political Heresies,” he reflects on

“trying to square your liberal principles with your sense that people who are

with you on most things—on the obligation to move the world as it is closer to

the world as it should be—are increasingly suspicious of dissent.” Boyers comes

to the conclusion that an unwillingness to hear non-progressive points of view,

an obsessive focus on “privilege” (a term he thinks is being used

indiscriminately), and an unwarranted concern about the idea of cultural

appropriation are occurring across the country and posing a danger to the

ideals of the academy.

I

recently spoke by phone with Boyers. During our conversation, which has been

edited for length and clarity, we discussed the difference between political

correctness and virtue signalling, why he thinks that we are too focussed on

the idea of “privilege,” and whether we are becoming more or less mature in

judging works of art.

Isaac

Chotiner :

Your

book begins by connecting the increasing focus on the concept of privilege with

the idea of virtue. Can you explain how you think the two are connected?

Robert

Boyers :

Privilege

is a term that has come more and more to be sounded in the culture, and there

is no question that it has a meaning we all know—that there is such a thing as

privilege, which has to do with advantage. The advantage can be earned or

unearned, but certainly there is such a thing as earned or unearned advantage.

What’s happened is that the term “privilege” has come to be used promiscuously,

so that it has become something of a noise word which is invoked to prevent

conversations from heading in directions that people would rather they not go

in. So that when a person is making a comment that you don’t like, you raise

your hand and you say something like, “Oh, do you realize that you’re

exercising a privilege in speaking this way?”

And, of

course, when certain epithets are attached to the word “privilege,” like “white

privilege” for example, or “male privilege,” they exacerbate or intensify the

charge, so that, in many cases, “white privilege” is a term that now is used to

signify something that all white people enjoy in the same way, simply because

it can’t be enjoyed by anyone who is not white. The problem with that, and I

think it’s fairly obvious, is that not all white people are the same. Not all

white people enjoy the same privileges. Not all white people have the same

backgrounds and experiences, and to think of white people in this sort of

indiscriminate way and to invoke the term “privilege” to talk about what they

enjoy is to be completely misleading about the lives of white people.

IC : What’s

the connection between that and virtue?

RB : Well,

if you constantly speak about people in that way, you are signalling your own

virtue by indicating that you are alert to the privilege that people enjoy,

with the implication, of course, that all of the privilege they enjoy is

unearned—even if these privileges that you’re speaking about are, in fact,

earned, or earned by people who have worked hard, people who have spent many

years in educational institutions to get where they are. And so you’re

signalling your virtue by accusing people of privilege in that way. And there

are many other ways of signalling your virtue by pointing out to people things

that they should not have said, things that they should not have thought, and,

in that sense, virtue signalling has become a common feature of life and the

culture, most especially in academic culture.

IC : I

think we are all aware of seeing someone tweet something because they want to

signal that they have some point of view. But it does seem, in a way, that the

term “virtue signalling” is a backhanded compliment, because it’s essentially

saying there is some virtue to it, or that it acknowledges an awareness of

racism or misogyny or a history of discrimination. So when you say “virtue

signalling,” are you saying that bringing up these issues in a discussion is

frustrating or annoying, even if somehow true? Or are you saying that you think

that these things are not actually accurate in some way? Or both? If that

distinction makes sense.

RB : The

distinction makes sense. I think that there’s a difference between [virtue

signalling] and pointing something out when, in fact, there is reason to do so.

If I’m in a room in which someone calls another person a horrific name, and I

say, “I’m sorry, but I can’t sit quietly by when you use a word like that to

speak to this person,” or if I say to a student, “I’m sorry, but in our

workshop we don’t speak to one another that way”—when we’re talking about

someone’s story that she’s written for this week, we don’t say, “I’m sorry, I

think that story’s stupid”—I don’t regard that as virtue signalling. It might

be virtuous for me to call the person on the thing that’s been said, but I

don’t do it to signal my virtue.

But

there’s a whole realm of discourse in which people call people out in order to

signal their own virtue, and that’s a very different sort of thing. Let me give

you an example. If someone confuses the names of two people who are black or

Asian-American, calling one by the name of the other, and you want to make a

very big deal of that instead of regarding it simply as a mistake, well, then,

it seems to me you are signalling your virtue. You’re making a great deal of

something which may simply be no more than a mistake.

I have a

whole chapter in my book about ableist language. If you make a big deal about

the use of expressions like, “We ought to learn to walk in someone else’s

shoes,” and you make a big deal about that because you’re afraid that people

who can’t walk will be offended or that their feelings will be hurt, it seems

to me you’re engaging in virtue signalling. That’s very different from calling

people out when there is actually a legitimate reason to do so.

IC :

It often

seems to me that there is too little awareness of historical injustices and

present-day injustices, and of how those injustices shape the world we live in.

It is the paradigm under which a lot of us operate, or all of us operate. But,

still, individual people should be able to talk about what they want and should

be judged on the content of what they say, not their specific experiences of

race or gender or so on.

RB : I

think you’re taking us in the direction of what I would call the distinction

between identity and identity politics, which seems to be a very important

distinction. We all know that there’s been a great deal of talk in the culture

in recent years about identity, which is an important and legitimate idea to

talk about. And it’s something that each one of us is concerned with, in our

own peculiar ways. I think about where I come from, who I am, how I got to be

the person I am, why I think the way I do, and so on. That’s entirely

understandable.

But when

we enter the realm of identity politics we’re talking about a tendency for

people of a particular race or religion or ethnicity or gender or social

orientation to form more or less exclusive political alliances and to think of

themselves as beholden in some way to that particular background experience,

set of experiences, or identity. And that’s a change to me, and legitimately

understandable for people who have been discriminated against and who have had

to live under certain burdens of oppression. Those people want to mobilize and

gather with people of a similar background and orientation and to achieve a

certain kind of power, on the basis of which they can hope to change the state

of things.

But

there are very unfortunate aspects of identity politics, which we’ve seen all

too much and which seem to me to have something to do with the question you

just put to me. There are insidious features of, or extrapolations from, this

tendency toward identity politics—most especially the notion that people of a

particular kind tend to be like-minded or to see and feel things more or less

in the same way. The worst part of this is the demand, not only the notion that

people of a particular background or experience or ethnicity tend to see and

feel things in this same way, but the demand that they continue to see and feel

things in the same way. That’s the direction we’ve been headed in, and I think

it’s both dangerous and deeply misleading.

I come

from a Jewish background. My grandfather was a rabbi, my father was a cantor.

Am I expected to think about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a Jew? Is it

expected of me that I will adopt a perspective that’s, shall we say, suitable

for a person of a Jewish background? Is that reasonable? In fact, I think about

the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a person who is also a left liberal, an

intellectual, a college professor, a person who’s had a whole range of

experiences, who reads many books about the Middle East. Why would I be

expected to relate to this particular kind of conflict solely by virtue of the

fact that I went to Hebrew school and that my grandfather was a rabbi?

Obviously, all identities are plural. I am many different things. I am not just

someone who went to Hebrew school, but the demand increasingly is that I should

think about things that way.

IC : When

you talk about the “demand,” are you talking about in the academy or across

society?

RB : We

see aspects of this in the general society and the culture, but it’s

particularly important and prominent in colleges and universities, where

students are encouraged to think of themselves in narrowly identitarian ways,

or basically as avatars of particular racial backgrounds. We have in colleges

and universities ethnic-studies programs, along with black-studies programs.

Nothing wrong with studying such subjects, by any means. But I would say that

encouraging students in those programs to think of themselves primarily in

terms of their race or ethnicity is terribly misleading.

IC : To

what degree do you feel that people are being encouraged to think that way by

other people in the academy, and to what degree do you think that people feel

that society views them primarily in that way, and so that ends up being the

identity that they’re most likely to express or to want to use to push back

against what they see is the way society looks at them?

RB : I

think there’s no question that people who have a personal experience of

oppression, who have felt that, will tend clearly to self-identify along the

lines suggested by that experience. So that, for example, if you’re an Islamic

person who lives in a city where there’s a great deal of anti-Islamic

sentiment, and you find yourself being looked at in ways that are distinctly

uncomfortable, you will tend to think about yourself as a Muslim principally,

and, of course, if you’re a religious Muslim, and your religion is the most

important thing in your life, then again you will tend to think of yourself in

that way. But the demand that the rest of us, who don’t live in those

conditions, think of ourselves in that way seems to me not only unreasonable

but misleading.

IC

: In the book, you write, “Intolerance

among young people and their academic sponsors in the university is more

entrenched than it was before, and both administrators and a large proportion

of the liberal professoriate are running scared, fearful that they will be

accused of thought crimes if they speak out against even the most obvious

abuses and absurdities.” Young people are generally toward the left, but even

on the left of the Democratic Party, candidates like Bernie Sanders and

Elizabeth Warren seem to have no interest in this sort of intolerance. There’s

no left-wing Trump, obviously. Do you feel this has any political

manifestations yet?

RB :

I don’t

know if it will change, and I don’t know if these aspects of the culture will

go all the way up to the Presidential race. I doubt it. Certainly, I doubt that

we’ll see anything like that in the near future. But the thing I’m describing

is definitely intolerance on the left, intolerance in my own cohort, intolerance

among young people and their academic sponsors in the university who think of

themselves as leftists and liberals, as I do. I give many such examples of

intolerance, and these are serious. Look at the people who, in a workshop of

the New York State Summer Writers Institute the year before last, attacked a

white student who had spent a year on leave working at Bryan Stevenson’s Equal

Justice Initiative, in Alabama. They attacked him for using material that he

had come by in the course of that year, because he had illegitimately

appropriated it as a white person from the experience of black people that he

encountered in his year. [Boyers, the director of the summer institute, at

Skidmore, describes the incident in his book.] That seems to me a mark of

intolerance—that young man was shamed and chastised in his workshop by students

who regard themselves as liberals, leftists, progressives, and passionate about

racial matters.

IC :

My

general takeaway from polling on young people is that you get more support for

not allowing speech that people perceive as bigoted. And then, if you ask

people questions about whether mosques should be able to be built or athletes

should be able to kneel before a football game without getting fired, they’re

actually more tolerant than previous generations. So I don’t disagree with you

that something has changed in certain ways, but it also seems like it’s a mixed

picture. Is that not your sense?

RB : Of

course, I think in my cohort there is considerable support for Colin Kaepernick,

as there should be. He should’ve been able to kneel, and he should be able to

use his hands in the way that he wanted to, to signal his allegiance to certain

ideas. Without any question. But, meanwhile, not only in the university but in

the larger culture, you see reflections of the thing I’m describing. I’m sure

you read about the pulling of the poem at The Nation in the summer of 2018, on

the grounds, again, that the white poet had used the language of black

speech—and this was found to be illegitimate after the poem had been accepted

and published in The Nation. And I know you’re aware that, in the publishing

world, there is a considerable momentum behind the notion that authors ought

not to be publishing books or stories about or in the voices of persons who

belong to groups different from their own. There are agents, powerful agents in

New York, who will no longer send out a story by an author dealing with

characters who don’t belong to that author’s own racial or ethnic group. That’s

real. That’s happening.

IC

: You wrote a great essay years ago

about V. S. Naipaul and whether to separate the artist from the art, and I’m

curious what you think of the conversations that have arisen in the last few

years, especially around #MeToo and different works of art and how we should be

judging them now. Do you feel that that conversation has become, in some ways,

less mature or more mature?

RB : The

#MeToo movement has been an important, and, in most cases, highly beneficial

movement, and it’s done very important things for all of us and the culture. I

have misgivings about certain things that have happened under the auspices of

#MeToo. But, on the whole, it seems to me #MeToo has been extraordinarily

beneficial.

But has

the conversation about ideas, ideology, and works of art become more mature?

Decidedly not. There are large numbers of people who regard themselves as

liberals and progressives and so on who were involved in demanding that Dana

Schutz’s painting based upon the Emmett Till event be taken down from the walls

of the Whitney. There are people who mobilized last year to ask the

Metropolitan Museum to take down Balthus’s painting of “Thérèse Dreaming” from

the walls because, presumably, certain viewers of these works found them

offensive or disturbing.

That

doesn’t seem to be mature. Again, people are allowed to demand what they want

to demand and allowed to protest what they want to protest. I don’t regard

those kinds of things as mature at all. The argument against appropriation has

not, for the most part, been a mature conversation. A mature conversation would

ask the question that Zadie Smith asked about the Dana Schutz painting: namely,

does it give justice to the event—that is, the murder of Emmett Till—which it

purports to represent? That’s a mature, adult question to ask of a painting. An

immature question to ask of a painting is, “Is the person who made it white?”

IC : It

seems like the question of who’s doing the representation is an interesting

question, but it’s not the mature question about the quality of a specific

painting.

RB : The

term that Zadie Smith uses in her Harper’s essay on the question, or for the

concern with the race of the person who purports to represent an event, is

“philistine.” I agree with her entirely. She argued the Schutz painting is a

failure that doesn’t do justice to the event that it purports to represent.

That seems to me entirely legitimate. It’s a concern that we all have when we

read novels, when we look at paintings, and we ask, “Do these do justice to the

material that they handle?”

IC : Right.

It’s a mature or interesting question to ask what groups of people are doing

different types of artistic representation. If it were only white people who

were asked to cover foreign countries or to write book reviews about the

African-American experience, that would be an important thing to understand.

But I agree with you that to look at a specific review, or to look at a

specific person, and to judge their work by the color of their skin rather than

the content of the art or the journalism that they’re creating is much less

mature.

RB : I’m

entirely in accord with what you just said.

IC : I

grew up in Oakland and Berkeley in the eighties and nineties, and there were

things as a teen-ager that I found really frustrating about political

correctness. I felt people were kind of moralistic in the way they talked about

the environment. I thought the way that they talked about inclusiveness was

really good, but also could be kind of silly, and you’d roll your eyes and say,

“Oh, it’s Berkeley, whatever.” Twenty-five years later, so much of that stuff

is conventional wisdom across the whole country. People pay much more attention

to the food they eat and to the environment, and most Americans have an opinion

on gay rights and trans issues. And that makes me think that, if there are

things that I find silly now, thirty years from now I’m going to look back on

them and say, No, those actually were good things. Do you ever think this,

despite your frustrations?

RB : Well,

yeah, of course. One of the reasons that I really don’t want to talk about

political correctness in my book is because there’s a sense in which, along the

lines that you were just describing it, political correctness is obviously a

very beneficial thing. It is wonderful that most people in a society like ours

can no longer feel comfortable using epithets, disgraceful and disgusting

epithets, to describe other human beings. We can no longer say the kinds of

things that people used to say about Jews, black people, Italians, Poles, and

so on. That’s an aspect of political correctness that I think most of us who

are decent human beings applaud and you live by, and we’re glad that political

correctness has, in that sense, had its way with us. But, on the other hand,

political correctness comes in many different guises, and political correctness

may also have to do with the demand that we not say things that, in fact, are

not offensive, that some people take to be uncomfortable.

IC : So

you are drawing a distinction between political correctness and virtue

signalling, which I agree are not the same thing, but it seems like they have

some overlap, no? What is the distinction?

RB : Virtue

signalling would focus on what are sometimes called microaggressions, which are

things, first of all, that are unintentional in many cases, accidental, and

which in many cases really don’t hurt anybody’s feelings, but which people who

are virtue signalling have taken hold of in order to emphasize their own

alertness and their own virtue. That’s very different from the kinds of

political correctness you were talking about.

IC : I

think, in a way, we acknowledge this point about political correctness when we

say we don’t want to judge people from twenty or thirty years ago too harshly

by the standards of today. If we are going to acknowledge that, then it also

seems like we should acknowledge that there were people thirty years ago who

had more forward-thinking opinions, and even if they sometimes annoyed us, they

were right, and so maybe the people who seem to have opinions today we find

frustrating are onto something.

RB : They

were right in some respects. In other respects they were not. Look, we have all

paid considerable attention in recent months to controversies involving the use

of the n-word. A professor at the New School for Social Research, a woman named

Laurie Sheck, got into trouble for reading out the word in a graduate class, in

a [statement] by James Baldwin. There was an article in the New York Times

Op-Ed page by the black writer Walter Mosley about the way he received

complaints and is brought up on charges for using the word. So those kinds of

circumstances in which writers and professors and intellectuals are being

called out for doing their jobs in the classroom seem to me to be aspects of

what I’m calling virtue signalling. And, yes, they are related to political

correctness, but they are decidedly different.

The True

and False Virtues of the Left. By Isaac Chotiner. The New Yorker , October

11, 2019

In

recent years, Skidmore College, where I am a professor, has been roiled by

political incidents large and small. As at other colleges and universities,

these eruptions have ranged from sometimes violent protests designed to prevent

controversial speakers from speaking to “call-outs” and disruptions to prevent

the teaching of ostensibly offensive books or to punish people for using

ostensibly offensive language.

In an

effort to encourage dialogue, the president of Skidmore recently invited a

scholar named Fred Lawrence to give a lunchtime lecture to faculty and staff.

As author of a book called Punishing Hate and the secretary of Phi Beta Kappa,

the nation’s oldest honor society, Lawrence seemed suited to offer advice about

the troubles we’d been going through on campus. How could we better

differentiate between offenses serious enough to warrant concern, and the more

minor slips or unintentional derogations sometimes called “microaggressions”?

“To be

unable to tell the difference between kicking a dog and accidentally tripping

over one is to have little hope of successfully navigating life on a college

campus,” Lawrence said, in a talk that was mild and notably free of polemic.

The

first faculty member to raise a hand after the lecture asked Lawrence whether

he was aware of the privilege he had exercised in addressing us. She spoke with

conviction, and suggested that Lawrence had taken advantage of his august

position by daring to offer his advice. Lawrence replied with courtesy,

conceding that, like everyone else assembled, he was of course the beneficiary

of several kinds of “privilege”, and would try to be alert to them.

Though

nothing further came of this exchange, it seemed clear that “privilege” had

been invoked as a noise word to distract from the substance of Lawrence’s

remarks and from his suggestion that some of us had failed to make the

elementary distinction he had called to our attention. More, the “privilege”

charge had been leveled with the expectation that he was guilty – not because

of anything particular he had said, but because he was a white male.

It was

hard not to think that my young colleague was in fact suffering from what

Nietzsche and others called ressentiment – a feeling of inferiority redirected

on to an external agent felt somehow to be the source or cause of that painful

feeling. Rightly or wrongly, she regarded him as the embodiment of a power, or

authority, that is nowadays conventionally associated with “privilege”; that

is, with some endowment or attribute – wealth, position, conviction, erudition,

benevolence – enjoyed by some people but not others.

Of

course there really is such a thing as “privilege”, and of course it is

distributed unequally in any society. You’d have to be a fool to deny that

whiteness has long been an advantage, however little some white people believe

that their own whiteness has given them what others lack. Can anyone doubt that

privilege is a real and legitimate issue when certain groups in a society enjoy

ready access to good healthcare and schooling when others do not? There was a

time, not so long ago, when to speak of privilege was to identify forms of

injustice that decent people wished to do something about.

But

you’d also have to be a fool to deny that the idea of privilege has been

weaponized in contemporary discourse, often by people attempting to seize

rhetorical advantage. The privilege call-outs increasingly common in the

culture entail a readiness to rebuke people simply because their gender,

ethnicity or rank makes them an apt target for shaming and condemnation. The

charge of “privilege” is usually directed at its targets not with the prospect

of enlisting them in some plausible action to combat injustice but instead to

signal the accuser’s membership in the party of the virtuous. Accusations of

“privilege” have become a form of oneupsmanship, and a charge against which

there is no real defense.

The

writer and linguist John McWhorter has written of “the self-indulgent joy of

being indignant”; for many in the academy, he notes, the “existential state of

Living While White constitutes a form of racism in itself”. In fact, he argues,

the standard “White Privilege paradigm” is designed to “shunt energy from

genuine activism into – I’m sorry – a kind of performance art”.

Those

words – a kind of performance art – sharply identify what has lately happened

and explain why many of us believe it is time to retire the term “privilege”,

or at least agree to use it only when it cannot be understood to describe a

self-evident crime. Not every advantage is unearned. Not every advantage is

misused. Not every white person enjoys privilege in the way that some white

persons do. Not all black people are without advantages.

In fact,

to speak of “privilege” in the way that is now customary is to suppose that

whiteness, or blackness, or maleness, or other such attributes, must signify to

all of us the same things. It is to consider a white person primarily as a

white person, a black person primarily as a black person, and to consign to irrelevance

the many other qualities that make humans different from each other.

Our

emphasis on “privilege” has served to obscure a great many things that ought to

be obvious. We cannot have a serious discussion about privilege without first

making elementary distinctions between one experience of race or advantage and

another. Until and unless we are prepared to renounce the “performance art”

phase of our relationship to “privilege” we ought to let it go.

The term

‘privilege’ has been weaponized. It's time to retire it. By John Boyers. The Guardian. November 8, 2019.

A

leading American Liberal arts college recently set out to hire a full-time

fiction writer. Four candidates made the shortlist out of 200 applicants. Each

candidate had to give a demonstration class to some students and field

questions from faculty members sitting at the back. One candidate called some

of the questioners by their first names. Unfortunately, he confused the names

of the only two Asian-American faculty in the department. This was obviously

not deliberate, just unfortunate. At a department meeting a week later, the

department chair made it clear that as far as she was concerned the writer

would no longer be considered for the job.

Why not?

He had made a mistake, at the end of a gruelling and pressurising day. Did

anyone think that mistaking the names of two Asian-Americans, who he had never

met before, made him a racist? Maybe yes, maybe no. In a liberal arts college

in America today, it was sufficient that there might be a suspicion that he

might not be able to tell two Asian-Americans apart for him to be considered

totally unacceptable.

This is

what has happened to universities in America and this is what has led Robert

Boyers to write The Tyranny of Virtue. Boyers, the founding editor of the

cultural magazine Salmagundi and professor of English at Skidmore College,

where this incident happened, has set out to explore this new culture of

intolerance.

How

could it be that in universities, of all places, free speech and the open

debate of ideas, could have become intolerable, not just to students but to

faculty and administrators? Why are academics running for cover, refusing to

stand up for tolerance? Worse still, why have they become the “new commissars”,

“fluent with anxiety about art that offends”?

Boyers

is not some right-wing reactionary. He may be considered privileged because

he’s a white man, but he was from a Jewish working-class family in Queens. His

father worked in a dry-goods store for 13 hours a day, six days a week. He has

been on the left for more than half a century, on what his academic colleagues

would consider the right side of political debates from civil rights and

Vietnam to Iraq and Trump. He has been, he writes, “a partisan in the ongoing

culture wars for about 30 years”.

This

isn’t some cranky polemic, raging against Bernie Sanders or Alexandria

Ocasio-Cortez. From beginning to end, this is a moderate, thoughtful book,

constantly questioning the rage for “purity”, the obsession with “safe spaces”,

the longing to “drink at this well of misinformation and grievance”. It is as

if he suddenly found that people who are with him on most things are

increasingly suspicious of dissent. How have American universities become so

illiberal?

The

Tyranny of Virtue is superbly written and full of interesting anecdotes. At his

college Boyers saw a sign that said, “KEEP SKIDMORE SAFE”. Of course. Who

doesn’t want to be in a college which is safe and protected from potentially

violent intruders? Women, gay and minority students have too often been victims

of attacks on American college campuses.

But this

isn’t what the sign meant at all. It was about “ableist language”, expressions

like “stand up for”, “turn a blind eye to” and “take a walk in someone’s

shoes”. These are apparently demeaning and offensive. A professor who talks

about turning a blind eye to something is offending someone who is visually

impaired. If you speak of having to “run” to catch a train, imagine how

insensitive this must be to someone who has problems walking.

This is

typical of an academic culture obsessed with harms, protections and all manner

of offences. Nothing is innocent. Intention is irrelevant. As Boyers writes,

“Just about every conversation had become a minefield.” Not just conversations,

every lecture, every comment in a seminar or to a student in a casual

conversation.

Someone

protests against “the screening of a ‘disturbing’ 1960s Italian comedy that may

trigger, in a person with her background, traumatic memories”. Boyers thinks

that he was “courteous and sympathetic”, but then she tells him “that as a man

you’ll never understand the problem”. Game, set and match.

A

student complains to Boyers about a set text by the white South African writer

Nadine Gordimer. It was “a bad idea” for a “privileged” white woman to be

dealing with people about whose lives “she was bound to be clueless”. And were

there particular instances in the novel, Boyers asks her, where Gordimer seemed

to her “clueless” and had got things wrong? She couldn’t say. “I felt very

uncomfortable about the direction we were heading in,” she says later in the

conversation. She didn’t like “the usual Western prejudices”. This is, of

course, not open for discussion. How she felt trumped everything.

For that

student it was Gordimer. For many others it will be Saul Bellow. “Who is the

Tolstoy of the Zulus? The Proust of the Papuans? I’d be glad to read them.”

With those few words Bellow destroyed his reputation in American literature

departments for a generation. Does anyone teach Bellow any more in America?

Perhaps Philip Roth can hang on for another decade, then he will make students

feel uncomfortable. All those angry accounts of what happened to black Newark.

All those men, all those jars of liver.

Boyers

moves carefully through these issues, from identity politics and diversity to

cultural appropriation and “policing disability”. The key word here is

“policing”. The thought police have taken over. Boyers is quick to point to

what gets ruled out. There is no room for diversity, complexity and ambiguity,

what Robert Pinsky called “the virtues of ‘creole’”. There is one right way of

viewing everything: a right way and a wrong way.

Boyers

is not alone, of course. He quotes others who championed tolerance and

diversity. Susan Sontag, who wrote, “Party lines make for intellectual monotony

and bad prose.” Edward Said, who called on us all to “abandon[s] fixed

positions, all the time”. But Said died in 2003, Sontag in 2004. That already

feels a long time ago. Boyers, decent, embattled, at times sounds like the Last

of the

Mohicans.

Even his son asks him if he puts too high a value on doubt and contradiction.

There is

a crisis in American universities and in Britain too. Intolerance reigns

supreme. Boyers quotes Jonathan Freedland: “What so infuriates opponents on left

and right is the insistence that two things, usually held to be in opposition,

can both be true.” No, say the commissars. If someone is a sexist, a homophobe,

a racist, there is nothing else that we need to know about them. We are the

saved, they are the damned.

And what

if they innocently muddle up two Asian-Americans or talk of “turning a blind

eye” to something? Also damned. Or if they insist on discussing a Shakespeare

play or an Italian comedy that makes a student feel uncomfortable? Double

damned. Reasonable, sane, decent, this is the right book at the right time.

Intolerable

intolerance. By David Herman. The Critic, December 2019.

Robert

Boyers discusses his new book “The Tyranny of Virtue: Identity, the Academy,

and the Hunt For Political Heresies. The Open Mind, hosted by Alexander

Heffner. Thirteen, January 20, 2020

For

every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. Newton’s Third Law deals

with physical objects, but does it also have something to teach us about human

behavior and the clash of forces in our fraught and turbulent society?

When it

comes to the volatile issues of race, sex, identity, privilege, rights, and

freedom, well-intentioned actions to redress genuine injuries can conflict with

equally important societal values, such as freedom of speech and the open

exchange of ideas. Are there unintended and adverse consequences that flow from

the energetic vindication of cherished rights in our society? Consequences that

have been ignored and deserve serious examination? Is there still any

legitimate place for dissent and disagreement on these fundamental issues?

In The

Tyranny of Virtue: Identity, the Academy, and the Hunt for Political Heresies,

Robert Boyers, professor of English at Skidmore College, author of 10 books,

and editor of the literary journal Salmagundi, is alarmed by the “irrationality

and anti-intellectuality” on college campuses and in the wider cultural

environment that was “unleashed by many of the most vocal proponents of the new

fundamentalism” to “silence or intimidate opponents.” He is deeply concerned

that

‘’concepts with some genuine merit — like

“privilege,” “appropriation,” and even “microaggression” — were very rapidly

weaponized, and well-intentional discussions of “identity,” “inequality,” and

“disability” became the leading edge of new efforts to label and separate the

saved and the damned, the “woke” and the benighted, the victim and the

oppressor.’’

He

regrets that “people who are with you on most things — on the obligation to

move the world as it is closer to the world as it should be — are increasingly

suspicious of dissent.”

Boyers

is asking whether in our zeal to address the consequences of racism, misogyny,

sexual violence, bigotry, and intolerance in America, are we spreading a new

intolerance, undermining cherished values of free and open discussion? The Tyranny

of Virtue prompts serious readers to take a second look at their own

assumptions as we try to navigate the troubles waters on which we so often feel

adrift.

The

force of Boyers’s book comes from the proximity of his own university

experiences to the issues he is confronting, the grounding he provides with

relevant examples to illustrate his arguments, and his bracing writing style

which consistently expresses difficult ideas in crisp and succinct language.

As

Boyers sees it, tendencies that alarmed him and others on the liberal left 25

or 30 years ago have grown more disturbing.

‘’Intolerance

among young people and their academic sponsors in the university is more

entrenched than it was before, and both administrators and a large proportion

of the liberal professoriate are running scared, fearful that they will be

accused of thought crimes if they speak out against even the most obvious

abuses and absurdities.’’

Boyers

offers a startling example.

An Ivy

League college senior in Boyers’s July 2018 New York State Summer Writers

Institute — a young white man — told Boyers he was denounced in a seminar by

several other students for writing poems based on his experience as a volunteer

in Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative in Alabama. “How dare he write

poems about lynching and the travails of oppressed people when it was obvious

that he has no legitimate claim to that material?” Boyers sarcastically asks,

echoing the all-too-sincere accusations leveled at the student. “Was it not

obvious,” Boyers continues, “that a ‘privileged’ white male, who could afford

to take off a year of college to work as a volunteer, really had no access to

the suffering of the people he hoped to study and evoke?”

Boyers

expands this example beyond the college setting by recounting another

controversy that unfolded in July 2018, when objections (which Boyers calls

“predictably nasty and belligerent”) were lodged against The Nation magazine

for publishing a short poem by a young white poet in which he used black

vernacular language. Within a few days the poetry editors who had reviewed and

approved the poem issued what Nation columnist Katha Pollitt called a “craven

apology” that read “like a letter from a re-education camp.” In The Atlantic,

the scholar of black English John McWhorter called the language in the poem

“true and ordinary black speech” and a “spot-on depiction of the dialect in

use.” He also noted the irony that, at a time when whites are encouraged “to

understand […] the black experience,” white artists who seek “to empathize […]

as artists” are told to cease and desist.

Boyers

is angry about what he sees going on in the institutions of higher learning to

which he has devoted his life’s work as well as in the society at large about

which he cares deeply.

‘’The revolution of moral concern, driven by

people in the grip of delusions I have attempted to anatomize throughout this

book, is clearly a bizarre phenomenon, fueled by convictions and passions that

have the appearance of benevolence but are increasingly harnessed to create a

surveillance culture in which strict adherence to irrational codes and

“principles” is demanded.’’

He sees

a “toxic environment that now permeates the liberal academy” that is

“increasingly drawn to denial and overt repression” including “speech codes and

draconian punishments for verbal indecorum or ‘presumption.’”

Unfortunately,

Boyers’s anger can get the best of him as he ascribes ugly motivations to the

targets of his denunciation. “It is decidedly not true that academics

mobilizing to punish dissident or ‘incorrect’ voices on their own campuses are

nevertheless operating with benevolent motives,” he defiantly declares. And it

is “not true than an ostensibly well-intentioned effort to prevent a young

white poet from imagining the lives of black people is an expression of genuine

concern for black people.” Why does Boyers assume the motives of those

concerned about cultural appropriation are not “benevolent” or “genuine”? For

someone so dedicated to freedom of speech and open debate, why not address the

merits of the arguments in these controversies without making groundless

assumptions and attacking the motivations of those with whom he disagrees? Isn’t