AM: Do you have any memory of shooting the films?

First

Trip to Bologna 1978 / Last Trip to Venice 1985 is the seventh book in a series

of titles about Furuya’s wife. In it, he revisits the first and final holidays

they spent together before her untimely death.

Between 1989 and 2010, Seiichi Furuya released a series of five books, titled Mémoires. They explored the relationship with his late wife, Christine Gössler, who tragically took her own life in 1985. Composed of portraits, the books chronicle the life they made together, focusing primarily on their day-to-day existence in Graz, Austria, where they met in 1978 and lived for six years.

Throughout the making of Mémoires, the Japanese photographer attempts to work through the emotional fallout of his wife’s premature death, hoping to gain not just a better understanding of their relationship, but also of Gössler’s own thoughts and feelings during what was an extremely intimate, yet at times strained relationship.

Between 1989 and 2010, Seiichi Furuya released a series of five books, titled Mémoires. They explored the relationship with his late wife, Christine Gössler, who tragically took her own life in 1985. Composed of portraits, the books chronicle the life they made together, focusing primarily on their day-to-day existence in Graz, Austria, where they met in 1978 and lived for six years.

Throughout the making of Mémoires, the Japanese photographer attempts to work through the emotional fallout of his wife’s premature death, hoping to gain not just a better understanding of their relationship, but also of Gössler’s own thoughts and feelings during what was an extremely intimate, yet at times strained relationship.

In 1983, Gössler was diagnosed with schizophrenia and, for the final two years of her life, was like “a shell with a closed lid”. Speaking last year in an interview with Aperture, Furuya said: “This lasted until her final day in Berlin in October 1985. It wasn’t until 2005 that I became fully aware that she was dealing with problems in her life alone.”

First Trip to Bologna 1978 / Last Trip to Venice 1985 is Furuya’s seventh book within this extensive body of work. It follows on from Face to Face (2020), which, for the first time since the photographer began working with his personal archive, includes photographs of him taken by her.

This release marked an important progression in the project, as Furuya showcased Gössler’s own participation in documenting their lives. “Finally, with Face to Face, Christine can be recognised as a creator herself,” he explains. “It’s another volume of Mémoires, with her being credited as the author of her own works.”

In First Trip to Bologna 1978 / Last Trip to Venice 1985, we witness yet another evolution in the project, this time in regards to the medium. All of the releases up until this point have consisted of still photographs. The latest book presents frames taken from videos shot on Super 8 film during the pair’s first and last trips abroad.

Furuya had almost entirely forgotten about the initial trip. “I found this film in the attic and was very surprised when I watched the digitised film on a screen,” he says. “No matter how many times I watched the video, I couldn’t recollect memories from the trip [to Bologna]. It got to the point where I doubted if I was even there with her.”

Acknowledging this gap in his memory, Furuya has focused on “creating a brand-new story” of the trip, reimagining this early experience in their relationship. These frames sit alongside images of the couple’s final holiday to Italy, shortly before Gössler’s death. Together, they continue Furuya’s three-decades long endeavour to give his wife “an eternal life”.

Seiichi Furuya looks back at the beginning and end of his relationship with his late wife. By Daniel Milroy Maher. British Journal of Photography, March, 2022.

Seiichi

Furuya, based in Graz, Austria, for almost fifty years, is an established

member of the European photo community and cofounder of the esteemed journal

Camera Austria International. But his departure from his native Japan to his

adopted country of Austria is not widely known. At the end of September 1973, Furuya

left from Yokohama on a Soviet cargo ship, arriving in Vienna in early October.

Furuya had been a student of photography at Tokyo Polytechnic University during

an increasingly turbulent time in postwar Japan. Between the university riots,

the anti–Vietnam War movement, and the anti–Japan-US Security Treaty movement,

Tokyo was like a battlefield. Furuya frequently participated in the

demonstrations with his camera. But as the movement cooled off, realizing that

there was no longer a place for him in Japan, he burned his negatives and left.

Furuya moved to Graz two years after his arrival in Vienna and soon connected with other photographers. He became a founding and active member of Fotogalerie im Forum Stadtpark, an artist cooperative organizing exhibitions and occasionally planning workshops with photographers, including Mary Ellen Mark and Ralph Gibson. In 1979, the group started the inaugural Symposion über Fotografie (Symposium on Photography), which occurred annually until 1997. The inaugural three-day symposium included participants such as Lee Friedlander, Robert Heinecken, Joseph Kosuth, and John Szarkowski. Furuya also served as liaison to many key Japanese photographers working at that time, including Shomei Tomatsu, Daido Moriyama, Masahisa Fukase, Miyako Ishiuchi, and Nobuyoshi Araki, helping many of them set up their first exhibitions in Europe. Around the same time as the launch of the symposium, Furuya collaborated with Manfred Willmann and Christine Frisinghelli to launch a new magazine, Camera Austria, the first issue of which was published in 1980.

Face to Face is the sixth volume of work Seiichi Furuya has published under a variation of the title Mémoires (1989, 1995, 1997, 2006, 2010). Unlike with the other five books, Furuya shares equal authorship in this edition: Christine Gössler’s gaze at Furuya, and his gaze at Gössler, intersect through photographs that each made of the other. While Furuya continues to work with the materials created during Gössler’s life—like an ongoing body of work that resulted from a trip they took to Bologna, among other images from their life together—he has stated that this is the last of the Mémoires variations. In these works, Furuya challenges us to think about what it means for an artist to go so deep into a single, emotionally charged body of work, made so long ago and revisited time and time again.

Furuya moved to Graz two years after his arrival in Vienna and soon connected with other photographers. He became a founding and active member of Fotogalerie im Forum Stadtpark, an artist cooperative organizing exhibitions and occasionally planning workshops with photographers, including Mary Ellen Mark and Ralph Gibson. In 1979, the group started the inaugural Symposion über Fotografie (Symposium on Photography), which occurred annually until 1997. The inaugural three-day symposium included participants such as Lee Friedlander, Robert Heinecken, Joseph Kosuth, and John Szarkowski. Furuya also served as liaison to many key Japanese photographers working at that time, including Shomei Tomatsu, Daido Moriyama, Masahisa Fukase, Miyako Ishiuchi, and Nobuyoshi Araki, helping many of them set up their first exhibitions in Europe. Around the same time as the launch of the symposium, Furuya collaborated with Manfred Willmann and Christine Frisinghelli to launch a new magazine, Camera Austria, the first issue of which was published in 1980.

Face to Face is the sixth volume of work Seiichi Furuya has published under a variation of the title Mémoires (1989, 1995, 1997, 2006, 2010). Unlike with the other five books, Furuya shares equal authorship in this edition: Christine Gössler’s gaze at Furuya, and his gaze at Gössler, intersect through photographs that each made of the other. While Furuya continues to work with the materials created during Gössler’s life—like an ongoing body of work that resulted from a trip they took to Bologna, among other images from their life together—he has stated that this is the last of the Mémoires variations. In these works, Furuya challenges us to think about what it means for an artist to go so deep into a single, emotionally charged body of work, made so long ago and revisited time and time again.

Yasufumi Nakamori: Face to Face [Chose Commune, 2020], published last year, is the first entry to the Mémoires series in ten years. Before diving into Face to Face, please tell us how you left Japan for Austria in the early 1970s and what you were doing before that in Japan.

Seiichi Furuya: At the end of September 1973, I left Japan from the Port of Yokohama on a Soviet cargo ship called Khabarousk and arrived in Austria’s capital Vienna in early October, along the way passing Nakhodka, Khabarovsk, and Moscow. Around 1970, I was a student photographer in Tokyo during what was known as a turbulent time in postwar Japan. Between university riots, the anti–Vietnam War movement, and the anti–Japan-US Security Treaty movement, Tokyo was like a battlefield. I was around twenty years old at the time. Although I didn’t belong to any particular group, I was one of those people who frequently participated in the demonstrations. For me, bringing my camera and taking photos did not preclude me from participating in the demonstrations. The highly charged atmosphere of the society gradually cooled off as the Japan-US Security Treaty was set up to renew automatically. When the turbulence ended, I started realizing that there was no longer a place for me in Japan, and that thought grew stronger over time. I had a friend who had left Japan earlier and was living in Vienna at the time. Eventually I left Japan under the pretext of visiting this friend. After spending two nights on the ship, we docked at Nakhodka. The moment I stepped onto the land, I thought to myself that I was probably never going to return to Japan. Right before leaving Japan, I burned all the photographic records of my bustling life in Tokyo.

Nakamori: Graz has been the base of your creative activities for forty-five years, during which you cofounded Camera Austria. When and for what reason did you move to Graz? Please talk about how you arrived at co-founding Camera Austria, especially your involvement with Symposion on Photography.

Furuya: After staying in Vienna for two years, I moved to Graz, which is the second largest city in Austria, and I have been here since. The biggest reason for the move was that I got a job at a camera store in Graz through an acquaintance whom I came to know through photography. While working at the store, I came to know others who shared interest in photography and eventually became a founding and active member of Fotogalerie im Forum Stadtpark, an artist-based voluntary organization. In the beginning, we organized about ten photo exhibitions a year and planned workshops of famous photographers from time to time. Some notable workshops that I attended include ones for Mary Ellen Mark and Ralph Gibson. Three years ago, I found in the attic some black-and-white Super 8 film, which had detailed footages of Mark’s workshop from 1979. In the fall of 1979, we started the inaugural Symposion über Fotografie [Symposion on Photography]. We invited a dozen or so guests from around the world who were active in photography and hosted a three-day symposium.

Americans including Lee Friedlander, Robert Heinecken, Joseph Kosuth, Allan Porter, and John Szarkowski also attended the symposium. As part of the brain behind the whole operation, Christine Frisinghelli was involved with the founding of both the organization as well as Camera Austria International. She was in charge of all the negotiations and translated the inadequate words of those of us who were self-claimed photographers into something beautiful. I remember it as if everything happened only a few days ago… driving to the airport to pick up Friedlander and Szarkowski, working on a draft version of what was going to be published about the symposium, Friedlander used a handmade lightbox which was stored in the darkroom up in the attic to copy slides he brought for the lecture. At the time, for Europeans and Japanese, the mecca of photography was America. Instead of us going over to America, we invited folks who were active on the frontline of photography in America to come over and it was a huge success. For the inaugural symposium, we also invited Shoji Yamagishi from Japan. Unfortunately, he passed away while still corresponding with me to finalize his lecture. Szarkowski paid tribute in front of his portrait at the symposium.

We hosted the Symposion on Photography every fall for seventeen years until 1997. In charge of Japanese affairs, I worked with Shomei Tomatsu, Daido Moriyama, Masahisa Fukase, Tsuneo Enari, Miyako Ishiuchi, and Nobuyoshi Araki, and probably helped many of them set up their first show or solo exhibition in Europe. While working on the symposium, we started planning for the publication of a photography magazine. Manfred Willmann of the organization and I worked on initial drafts of the new magazine while referencing the latest Japanese camera magazines that were getting delivered to my place every month. In 1980, the first issue of Camera Austria was published. At first, we thought about using our own photos and publishing the magazine under issue 0 as a pilot. Before we knew it, the magazine was published as the inaugural issue. I think it’s worth mentioning the origin of the name of the magazine: When contents of the first issue were mostly decided, we held a meeting in the basement of Forum Stadtpark to decide on its name. Six or seven members put forward their proposed names, but none of them got a decisive yes from the group. At the time, an acquaintance of mine who also left Japan, and was in the middle of his own wandering journey, shouted out the name “Camera Austria.” No one objected. I think that over the years Symposion on Photography has provided a platform to discuss and demonstrate the evolving definition and meaning of photographic expression through real-life examples. Meanwhile, Camera Austria continued to grow while keeping pace with changes that were happening at the symposium.

Nakamori: Please tell us how you met Christine Gössler, your life partner and a coauthor of Face to Face, who tragically took her own life in 1985.

Furuya: In February 1978, at Forum Stadtpark, I met Christine for the first time at the opening of a solo exhibition by Gwenn Thomas called Color Photographs. Christine came with another woman who was a mutual acquaintance of both Manfred Willmann and mine. Ten days later, I mustered up the courage to call her and asked her to watch a movie together. We saw the Japanese movie Harakiri. From that day on, our lives became inseparable. Looking back, I realize that our relationship started with a movie about suicide, and ended with her own suicide. In mid-March of that year, we went to Bologna for a week. According to her notebook, I made up my mind to marry her while we were in Bologna. One week after returning from Bologna, I went back to Japan for the first time since 1973 and Christine came with me. During our two-month stay in Japan, we took part in a Shinto-style wedding ceremony at my home in Izu, and with that our relationship quickly moved on to the next level. Thinking back, it may have been the happiest time for us, although she seemed a bit caught off guard by the sudden change in environment. Shortly after returning from Japan, I quit my job at the camera store and started a new phase of life without a regular job. Christine was aiming to complete her thesis at university, but she eventually gave up and started working for the Austrian National Broadcasting Corporation.

There is an old passage that I wrote that describes, in simple terms, our encounter and how I felt about her. The passage was included alongside a portrait of Christine in the first issue of Camera Austria in 1980. It implied a deep connection between the human encounter and the characteristics and essence of photography as an expressive medium. So much so that it wouldn’t be strange to say that the passage could also have been written for Face to Face, published in 2020.

“From the first day I began taking photographs of her regularly. I have seen in her a woman who passes me by, sometimes a model, sometimes the woman I love, sometimes the woman who belongs to me. I feel it is my duty to continue to photograph the woman who holds so many meanings for me.

When I consider that taking photographs means fixing time and space, then this work—the documenting of the life of one human being—is exceptionally thrilling for me. In facing her, in photographing her, and looking at her in photographs, I also see and discover “myself.”

Nakamori: After Christine passed away, you edited and published several different editions of Mémoires featuring photographs from her life. I was wondering if all of that might have helped you get to know her better.

Furuya: In 1981, our son was born. Around the summer of 1982, the three of us left Graz and moved to Vienna. By that time, Christine had already started producing her own radio program at the Austrian National Broadcasting Station. One day, out of the blue, she said to me, “I want to be an actor. I want to be on the stage. It’s a dream I’ve had since I was a kid.” I was against it. After having lived together for four years by then, I honestly didn’t think she had what it takes to get through all the hardship that’s necessary in order to become an actor. I thought I knew her sensitive and compassionate personality. I thought I knew how, despite her modesty and tendency to not show her true feelings and thoughts, she was the type of person who would devote herself completely to something. However, as someone who didn’t have a job with steady pay and was at the mercy of Camera Austria, I strongly felt responsible for the impoverished life my family was going through, and thus I couldn’t convince her otherwise. When she started taking private lessons in order to matriculate at a theater college, Christine became like a shell with a closed lid and stopped talking to me about not just theater, but also things in her daily life. This lasted until her final day in Berlin in October 1985. It wasn’t until 2005 that I became fully aware that she was dealing with theater and other problems in her life alone.

Nakamori: Please tell us how Face to Face came about. You published five photobooks from 1989 to 2010 under the title Mémoires (all with Christine as subject). What’s the relationship between those five books and Face to Face?

Furuya: In the summer of 1987, I went back to Graz from East Berlin. It was when I started organizing her belongings that I discovered her notes. But I didn’t have the courage to read them right away. I was afraid that it was something that I either couldn’t bear to know or didn’t need to know. The notes were handwritten in German, so it wasn’t like I could easily read and understand them anyway. If they were written in Japanese, I’m sure things would have been different. It wasn’t until almost twenty years after her death, around Christmas 2005, that I finally decided to find out what the notes were about. I asked a girl who was a total stranger working part-time at the Graz Art Museum to reproduce a clean copy of the notes. I read and reread that clean copy carefully during a two-month stay in Paris. I hadn’t hid any secrets from Christine and always thought that I was living a straightforward life. However, Christine’s notes revealed that she’d become obsessed with theater and was increasingly struggling with her own limits while dealing with her mother and our child. I was shocked to read that at some point, she thought her theater instructor had become the only person who could forgive her, like a true mother. I didn’t know any of this, and it was as if I was reading about a different person. For me, the expressive power of her notes was beyond what photography could achieve. There were quite a few parts of her notes that even the female student who reproduced the clean copy couldn’t fully understand. In 2006, I published the fourth edition of Mémoires [titled Mémoires 1983] using portions of her notes along with photos.

After Christine killed herself in East Berlin in 1985, I worked there for two more years, finishing my job as an interpreter. In the summer of 1987, I returned to Graz to reunite with my son. On June 12, 1987, President Reagan delivered his “Tear Down This Wall” speech to Gorbachev on the west side of the Brandenburg Gate, which was also a symbol of the division between East and West Berlin. I listened to the speech along with many Stasi, National Secret Police of East Germany, on the east side of the gate. Of course, for someone who always carried a camera, I took photos of this historic occasion. Although at the time, no one, including probably President Reagan himself, foresaw that just two years later the Berlin Wall would come down along with the collapse of East Germany. In 2010, the fifth and final volume of Mémoires was published, which documented our lives moving from Dresden to East Berlin in 1984 and up until my return to Graz in 1987.

In 1989, my solo exhibition was held at the Neue Galerie Graz [the state museum of modern art in Graz]. The first edition of Mémoires was published at the same time. Meeting the museum director to discuss the name of the exhibition, I suggested a few names, such as Travelogue. But it took a while for us to agree. Eventually, the director said that what I was thinking about and trying to do would fit well with the French word mémoires. Thus, the name of the exhibition and my photobook was born. The exhibition was supposed to be important for both commemorating Christine and for sorting through my own feelings. It toured Vienna and Tokyo, and in the midst of changing venues, I felt that something new was stirring inside me. This feeling first came about when the 1995 edition of Mémoires was published, and lingered over the course of publishing the 1997 and 2006 editions, and even when I published what was meant to be the final iteration of Mémoires in 2010.

I publicly announced, at my solo exhibition at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography [formerly the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum] in 2010, that this would be the final publication in the Mémoires series. I felt that no matter how many times I tried with the publications of these photobooks, I didn’t really understand anything new. At the same time, I wanted to work on a book of my works that were not directly related to Christine. However, I had a stroke just before the exhibition in Tokyo, and it took me at least five years to recover. Since the announcement in 2010, I avoided works related to Christine and spent my days away from photography to focus on recovering my health.

Nakamori: What brought you back to photography and back to the world of Mémoires?

Furuya: Something came along out of the blue. At the end of 2017, the director of a photography museum in Japan reached out to me about doing a solo exhibition. While on the phone, I had this sudden feeling that I was being pulled back into the world of Mémoires. I was surprised, as I had been avoiding it until then, but the feelings just rushed in as if bursting through a dam. But this time, there was a definitive difference from the previous books, as I thought about presenting mainly works done by Christine herself for the exhibition. With only a few exceptions, the different editions of Mémoires had mainly presented photos that I took of Christine. Over the years, I was consumed with my own works, and I didn’t realize that Christine was a creator in her own right, with works expressing herself, until some thirty years after she passed away. To prepare for the exhibition, I started organizing her belongings, which had been stored in the attic for decades. I found her writings, Super 8 footage, cassette tapes, 110 film—things that I had forgotten about or saw for the first time. There was a reversal film of me standing behind a tripod with a 6 by 7 camera, which was taken on the coast of my hometown of West Izu in 1978. Christine must have taken that picture while I was taking a portrait of her standing on the edge of the cliff, with a Leica camera strapped around her neck, wearing tall, black rubber boots and carrying a bamboo stick. I was excited to have discovered this and found myself uttering the words “face to face.”

I arrived at Face to Face after going through five volumes of Mémoires. In a sense, my photos in each of those books are the starting point to make sense of the tragedy and mystery of the woman that is Christine. It was difficult for me to dismiss her death simply as a result of schizophrenia, which is a standard response given by society these days. Some friends tried to comfort me by using this standardized response. But after going through trial and error for over twenty years, the sad truth remains that I still don’t fully understand why it happened. Finally, with Face to Face, at least Christine can be recognized as a creator herself. It’s another volume of Mémoires, with her being credited as the author of her own works.

Nakamori: A key difference between Face to Face and your other works is the alternation between photos you took of Christine and photos that she took of you. Please tell us about the challenges of making and editing a photobook that focuses on the intersection of two creators.

Furuya: I was hoping to find more photos that Christine took. As if answering my prayer, I found 110 film negatives that I didn’t know existed, as well as color negatives from a 35 mm camera from when she started taking photos again in 1985. Eventually, it became clear that Christine was often taking pictures of me, and that we were taking pictures of each other at almost the same time. The act of taking photos and having our own photos taken continued, with varying frequency, until the day before she took her own life. On top of that, the hardest part was finding myself in my own photographs. I carefully checked the photos that I took from the time I first met her until I lost her, because sometimes she took photos of me with cameras that I was using. I made prints from selected films, arranged them in chronological order, and started to look at them carefully. The exhibition hall for Camera Austria was an ideal place for doing so. When viewed side by side, the prints were about twenty meters long. Just when the prints were completed such that they would fit nicely with the layout of the venue in Japan, we heard the news that the exhibition had been canceled. At the beginning of 2019, I immediately switched from planning an exhibition to planning a photobook, and carried on working. At that time, after having finished the selection of photos and arranging the material in chronological order, I selected the Marseille-based Chose Commune to be the publisher. I was told that Cécile Sayuri Poimboeuf-Koizumi was the editor in charge, and I entrusted the production of the book to her. If the editor wasn’t a woman, I’m not sure that I could have entrusted the whole process to someone else. Instead, I was completely hands-off.

I was shocked when I viewed the printed photobook for the first time in December 2020. After opening the cover and going through the pages, I almost felt that the two people in the book were talking to each other. It was like traveling back in time and space. I didn’t realize this when I was still preparing for an exhibition. I’m sure it has a lot to do with the binding of the photobook and the layout of each page. When the book is closed, the two people are still and facing each other, just like the title, face to face. But when you turn the pages, it’s as if a switch has been flipped, and the two people start to move and talk to each other. I reread the book and it felt the same every time. Maybe it’s something only I can experience, since I know the background of the photos. I also thought that might be what it means to have a book of moving pictures for adults. Some might simply think that what’s happening here is two people staring at each other and trying to read into the meaning of each other’s facial expressions, but one should be mindful that such reproduction of the act of staring is only made possible by the incredible invention of photography. Capturing a momentary image is one of the most salient characteristics of, and the original purpose of, photography. In that sense, what you see in terms of two people’s facial expressions satisfies that aspect of photography very well. But I can’t help but feel that those photos also express something beyond that. This is something that one becomes aware of only after a photo, which captures a past reality, is taken, and it’s something that is almost impossible to experience in real life. Even on the occasions when we take photos of each other, everything is a series of moments that keep changing. The moments when we stare at each other are so fleeting amid the passing flow of time that it is impossible to consciously read into and interact with each other mentally there and then. Photography is the only expressive medium through which we can relive and reconfirm a moment from the past. In that sense, I think Face to Face is a perfect embodiment of the magic of photography.

Nakamori: What does the act of taking photos mean to you? What does making and publishing photobooks mean to you?

Furuya: While thinking about how to respond to this question, I realized that I had never thought about the meaning of taking photos. I just always took photos before thinking about meaning or purpose. But for the last ten years, I haven’t taken many pictures. The reason is simple—things are less visible to me now, and my inner desire and need to take photos are not what they used to be. I think one of the reasons is that I have had almost no chance to expose myself to the vicissitudes of today’s world, and the lifestyle or habit of always carrying a camera with me wherever I go has largely gone away. For a while, I was taking pictures with a digital camera for blogging. Starting about a year ago, I’ve been taking photos of my grandkids and the change of seasons in my garden with my mobile phone. But at the end of the day, for me, a photo is a copy of reality printed on film that can be touched by hand. I have no interest in creating “artworks” using the medium of photography. For me, photography is the act of quickly capturing an image that approximates a premonition we feel when encountering moments of anxiety or interest in daily life. In my case, it can also be said that the act of taking photos, instead of, say, writing, is a way for me to record my impression and experience of encountering things that I can’t comprehend even through imagination, but is somehow connected to my existence. I’ve been called a “boundary” photographer by some. In fact, one of my works is called Boundary and I took photos of the Berlin Wall, but many portraits of Christine also portray the boundaries between people. It doesn’t matter if the quality of a photo is good or bad; it is no longer my concern in the moment it’s taken. Then, when it revives with the passage of time, it becomes the first time for me to face a photo that I once took.

I think that making a photobook is like assembling chaotic and complex images toward one big theme in your head. As the work progresses, the outline of the theme becomes clearer. I think it might be similar to how a composer writes a symphony by combining individual notes. For me, with the exception of my first photobook, AMS [Edition Camera Austria, 1981], I keep making photobooks so that I can bring them along with me when I eventually meet Christine again. Maybe they can also be called reports. There is another important reason why I keep making these photobooks—it is to tell our son and our grandchildren what kind of a person she was in ways that I could never do with words. The day after Face to Face arrived from Chose Commune, I brought it with me to the front door of my son’s house. There were strict rules in place related to the novel coronavirus. My son was fearful that I might contract the virus from my grandchildren, so we didn’t see each other. It seems that my son was more worried than I was about older folks getting infected. In Face to Face, my son showed up on many of the pages. Since this was his first time seeing these photos, I wasn’t sure how he would react. I was told that later that night, he read the photobook with his eldest daughter, who was six years old at the time. They seem to have enjoyed the book, and he was asked a lot of questions. My granddaughter was a little confused at first since her grandmother, Christine, looked youthful in those photos.

Now that I’m over seventy years old, I feel that I don’t need to hide anything anymore. There are a few reasons why I’ve published photobooks and portraits of Christine again and again over the years, but there’s one key reason that I’ve never publicly stated. That is, I want to help accomplish her childhood dream of standing on the stage—a dream that tormented her and may have forced her to kill herself. For example, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and MoMA in New York have collected several photos of her, and her portrait on the coast of Izu in 1978 was just exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Seeing her smile at me with that same bamboo stick, this time in New York, I couldn’t help but go up to the photo and talk to her. I never thought I could meet her again in such a place. I will continue to publish works of her and works by her, all of which always contain my unwavering desire to give my deceased wife an eternal life.

Nakamori: What do you think about COVID-19 and the resulting lockdown of cities and nations from last year to the present day? Also, please tell us what you are currently working on or would like to work on in a situation like this.

Furuya: It has been exactly one year since measures to battle COVID-19 were issued here in Austria [as of March 2021]. It actually has been a very fulfilling year for me. Thanks to the lockdown, I was able to focus on work that required a lot of patience and concentration. From the non-stop and inescapable news cycle about the virus, the idea that has related to me the most is death. From the moment of birth, a person begins their journey toward death. Yet, for a period of time, there is no need to think about the idea or meaning of death, so one is not aware of death and thinks that death has nothing to do with them. One might even think that they can live forever. After the age of seventy, death creeps into our life on many more occasions, while the eventuality of our own death remains ever more present. In my case, death is neither unpleasant nor frightening, and recently I’m even starting to feel that confronting death can make one feel refreshed. There is a tall gingko tree in my garden. I used to totally ignore its existence. These days, I watch the tree change throughout the seasons and think about the fateful encounters in life. Some of us live to be thirty-two years old, others to seventy-something years old, and yet others to a thousand years old (since I was a child, I’ve heard that gingko trees can live to be a thousand years old). I spend my days meditating on the trajectory and stories of my life, while being amazed at the small miracle that I got through all the trials and tribulations in my life since leaving Japan, and that I’m still around. Since we are still required to refrain from social activities to fight the virus, this is not a bad way to spend my otherwise solitary life.

At the moment, I’m getting started on the production of a new photobook called First Trip to Bologna. The book consists of materials from our trip to Bologna shortly after I met Christine in 1978. I plan on using only frames from videos taken with a Super 8 camera instead of the still photos that appear in this book. I also found this film in the attic and was very surprised when I watched the digitized film on a screen. No matter how many times I watched the video, I couldn’t recollect memories from the trip. It got to the point where I doubted if I was even there with her. It’s as if days that I didn’t know existed were brought back and recreated in front of me. Since I don’t remember anything, I thought about creating a brand-new story of the Bologna trip for us. In addition, I would like to publish a collection of photos taken solely by Christine. I wonder which project would come first, but I hope to bring this photobook with me as a souvenir when I see her again. I want to leave behind records of Christine’s works for our son and his kids. For me, the days of taking photos are mostly over. From this point on, I think my job will be to work with the newly discovered materials belonging to Christine and bring them to the public as her own works as much as possible. Other than that, I would probably continue to take family photos of my son and grandchildren with a 6 by 7 camera from time to time.

Nakamori: Thank you very much.

This piece originally was published in Issue 019 of The PhotoBook Review. Translated from Japanese to English by Shiwei Yin.

A Japanese Photographer’s Bittersweet Archive of His Late Wife. By Yasufumi Nakamori. Aperture, September 22, 2021.

In 1973,

the photographer Seiichi Furuya left his native Japan for Europe by

Trans-Siberian rail. He met Christine Gössler, a student of art history, in

Austria in 1978, and after a few months’ courtship the two married. Furuya

documented their bohemian life in Iron Curtain-era Europe: travel, cigarettes,

apartments that still appear stylish across the distance of time. Eventually,

he started an art magazine, and she was drawn to a career in the theatre. They

had a baby and settled in East Germany. A few years later, Gössler died by

suicide.

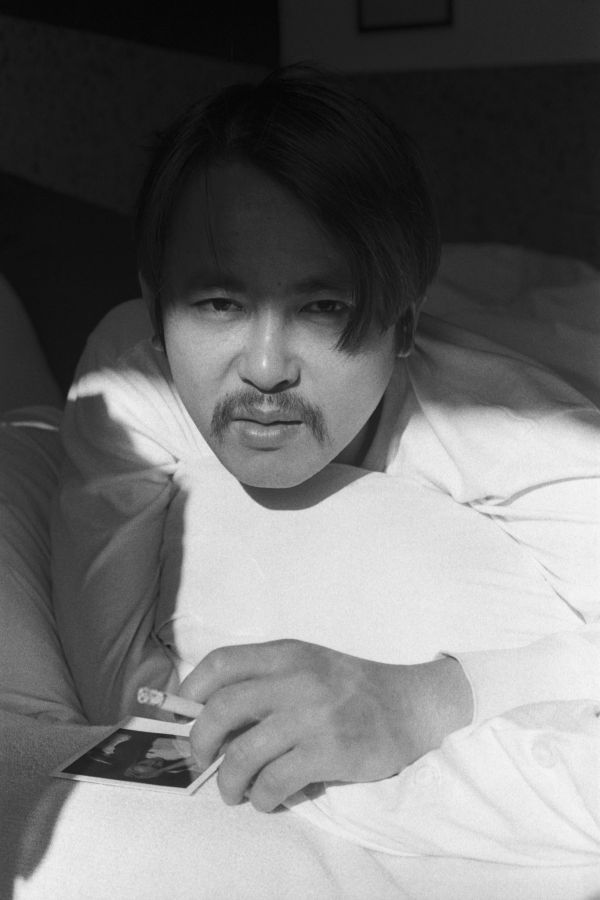

In the course of their relationship, Furuya had photographed his wife regularly, though I think it would be wrong to describe Gössler as her spouse’s muse—a term that suggests the model as object. Furuya’s images were quotidian in a way that seemed to presage our contemporary relationship to the medium. But even decades on, his late wife remains Furuya’s great subject. He has published five volumes—collectively titled “Mémoires”—containing portraits of Gössler and scenes captured from their brief life together. For his new book, “Face to Face,” Furuya returned to his archive, where he found something unexpected: images that Gössler had taken of him, sometimes documenting the very moment in which Furuya was photographing her.

There’s a simple elegance to the presentation of “Face to Face”: we see her, then we see him. Sometimes the two are posed against the same backdrop (a blue sofa, or the stucco wall of a house, with a flowering tree in the foreground); sometimes they’re undressed; sometimes they’re in black-and-white; sometimes they’re with other people. Often the pairings show us two vantages on a single moment: resting on a log, skis sticking out of the snowbank behind, or on a train, facing each other, an anonymous station glimpsed through the window.

The book is organized so that Gössler appears mostly on the verso, her husband opposite. This rhythm breaks, occasionally, suggesting that some special attention is warranted: see Furuya, nude and backlit, a shadowy form on a beautiful parquet floor, and his wife, also obscured by the contrast of light in the window behind, with her hair in a girlish side ponytail.

It’s hard not to be seduced by the couple: they are young, cool, dressed in chic clothing that one might mistake for contemporary. Their domestic bric-a-brac—a red plastic-topped soy-sauce decanter, blue-and-white ceramic bowls, a package of cigarettes at the ready—seems instantly recognizable to me. I was eight years old, with a bowl cut not unlike that of their son, Komyo, when this picture was taken, and even the way the sunlight filters through the lacy window panel feels somehow familiar.

In the course of their relationship, Furuya had photographed his wife regularly, though I think it would be wrong to describe Gössler as her spouse’s muse—a term that suggests the model as object. Furuya’s images were quotidian in a way that seemed to presage our contemporary relationship to the medium. But even decades on, his late wife remains Furuya’s great subject. He has published five volumes—collectively titled “Mémoires”—containing portraits of Gössler and scenes captured from their brief life together. For his new book, “Face to Face,” Furuya returned to his archive, where he found something unexpected: images that Gössler had taken of him, sometimes documenting the very moment in which Furuya was photographing her.

There’s a simple elegance to the presentation of “Face to Face”: we see her, then we see him. Sometimes the two are posed against the same backdrop (a blue sofa, or the stucco wall of a house, with a flowering tree in the foreground); sometimes they’re undressed; sometimes they’re in black-and-white; sometimes they’re with other people. Often the pairings show us two vantages on a single moment: resting on a log, skis sticking out of the snowbank behind, or on a train, facing each other, an anonymous station glimpsed through the window.

The book is organized so that Gössler appears mostly on the verso, her husband opposite. This rhythm breaks, occasionally, suggesting that some special attention is warranted: see Furuya, nude and backlit, a shadowy form on a beautiful parquet floor, and his wife, also obscured by the contrast of light in the window behind, with her hair in a girlish side ponytail.

It’s hard not to be seduced by the couple: they are young, cool, dressed in chic clothing that one might mistake for contemporary. Their domestic bric-a-brac—a red plastic-topped soy-sauce decanter, blue-and-white ceramic bowls, a package of cigarettes at the ready—seems instantly recognizable to me. I was eight years old, with a bowl cut not unlike that of their son, Komyo, when this picture was taken, and even the way the sunlight filters through the lacy window panel feels somehow familiar.

But Gössler’s eventual death looms, even when the pictures provide us only a smiling new mother with a baby in a comical bonnet. As we watch the woman change over the years, we do what the photographer must himself be doing in revisiting the pictures: we hunt for clues. Shots that are playful, or even sexy—she’s sprawled on a bed, hands pulling her hair from her face; he’s in the same bed, a cigarette in hand—seem almost mournful. Here’s a casual nude of a pregnant Gössler, standing before a bassinet; does she look haunted, or irritated, or merely tired? Here she is a couple of years on, hair fashionably shorn, her body no longer full with child—is she worryingly thin, possibly ill? The pictures do not yield easily to our scrutiny.

Furuya’s act in capturing his subject is one of pride, affection, desire, and maybe possession. If it’s also an act of art, Gössler, in photographing her photographer, transforms the thing into something closer to a game, a way of showing that she sees him as clearly as he sees her.

How many times, trying to capture whatever it is that we all feel compelled to remember these days (an especially photogenic cappuccino, my children doing something cute) have I fumbled, making the phone turn its eye back to me? I have dozens of these accidental, unflattering self-portraits, the inconvenient by-product of our era’s almost-too-efficient technology. I wonder how Furuya felt, suddenly confronted with his younger self—long hair, turtleneck sweater, wire-rimmed glasses. I hope he felt some solace. Gössler’s pictures of him aren’t just technical blips. They’re a message, dispatched across decades: I remember, too.

A Photographer, Seen Through the Eyes of His Late Wife. By Rumaan Alam. The New Yorker,

February 14, 2021

Artist page Choose Commune

Seiichi Furuya website

No comments:

Post a Comment