If you

happened to wander the puzzle-box warren of exhibit halls and saloons that made

up Phineas Taylor Barnum’s American Museum in the mid-1800s, no one would have

blamed you for feeling bombarded. Frankly, that was sort of the point: this

five-story destination in lower Manhattan was a living, thrumming organism that

strove to do nothing so much as overwhelm the senses. For a quarter’s

admission, visitors could take in fine portraiture and exotic taxidermy, live

theater and a lemonade stand, antiquities both real and imaginary, wax

sculptures, stereographs, a Canadian beluga whale in the basement aquarium, and

— capitalizing on an American strand of the Victorian-era “deformito-mania” — a

rotating assortment of human, biological rarities, whose unusual bodies

demonstrated the breadth and depth of creation.

Some of

these “living wonders” walked the venue’s halls, speaking with guests and

offering souvenir carte-de-visite photographs for sale. Other performers were

presented to the public in grand staged receptions known as “levees”. Alongside

the likes of conjoined twins, a seven-foot “giantess”, the bearded lady, and

the celebrated General Tom Thumb in his Napoleon costume was an act that

endured through Barnum’s era and into the twentieth-century sideshow: an

enigmatic, captivating woman known as the Circassian beauty, whose only

“deformity” was her lack of imperfection.

A staple

of dime museums and traveling shows throughout the nineteenth century,

Circassian beauties were alleged to be from the Caucasus Mountain region, and

were famous for both their legendary looks and their large, seemingly

Afro-textured hairstyles. The Circassian beauty was an attraction that required

audiences to hold a number of ultimately unresolvable stereotypes in tension

with each other. These women were presented as chaste, but were also billed as

former harem slaves. They were supposedly of noble lineage but appeared as

sideshow attractions. And they were displayed to predominantly white audiences

for an exoticism that traded on hair associated with Black women, which came

coupled with the paradoxical assurance that, being Caucasian, Circassian

beauties represented the height of white racial “purity”.

The

pseudoscience of race in the nineteenth century, the development of mass media

and entertainment venues at that time, and the employment of women who

performed race as though it were a theater role all combined in a jarring and

beguiling mix of stereotypes that kept the Circassian beauty attraction going

for decades, and has had a lasting impact on how we think about race, class,

and gender today.

This

particular conception of Circassian beauty can be traced to Johann Friedrich

Blumenbach (1752–1840), a German theorist who used craniometry — the measuring

of human skulls — to address the then-pressing scientific question of whether

racial variety was evidence of separate species within humanity. Blumenbach

firmly dismissed this idea, writing that the color of one’s skin was “an

adventitious and easily changeable thing, and can never constitute a diversity

of species”.

This is

not to say that everyone was equal in esteem according to the German

craniometrist. Blumenbach advocated for a hierarchy that considered people of

his own race to be humanity’s poster children. Assessing and comparing the

contours of various human skulls, Blumenbach ultimately arrived at a taxonomy

of five racial groups, among which he considered persons from the Black Sea region

to be the physical ideal. He coined the term “Caucasian” to describe this group,

writing that

“I have

taken the name of this variety from Mount Caucasus, both because its

neighbourhood, and especially its southern slope, produces the most beautiful

race of men, I mean the Georgian; and because all physiological reasons

converge to this, that in that region, if anywhere, it seems we ought with the

greatest probability to place the autochthones of mankind. ‘’

Blumenbach

considered this Caucasian population, spread across Europe, Western Asia, and

North Africa, the “primeval” (or “autochthonous”) human race, which branched

into four other categories: Mongolian (Central Asian), American (Native), Malay

(Southeast Asian), and Ethiopian (sub-Saharan African). It was, he argued,

environmental conditions that caused a “degeneration” of the fair Caucasian

original into peoples of color.

To

support his assertion that white skin had to be humanity’s default starting

point, Blumenbach needed little more data than the fact that European ladies

who spent their winters indoors exhibited “a brilliant whiteness”, while those

who “exposed themselves freely to the summer sun and air” quickly ended up with

a solid tan. “If then under one and the same climate the mere difference of the

annual seasons has such influence in changing the colour of the skin”, he

reasoned, ad absurdum, “is there anything surprising in the fact that climates.

. . according to their diversity should have the greatest and most permanent influence

over national colour”. The Ethiopian and Mongolian races Blumenbach considered

“extreme varieties”, with Native American and Malay, respectively, as

“intermediate” classifications between these extremes and the Caucasian ideal.

Blumenbach

may not have become especially famous, and craniometry (along with phrenology,

a sister pseudoscience devoted to divining personality from the bumps on one’s

skull) only had a short period of dubious fame, but the stereotype of idealized

Caucasian beauty caught on fast. Circassia, a region of the Caucasus Mountains,

became ground zero for Western notions of white beauty. Throughout the

nineteenth century, books and magazines extolled the virtues of fair, buxom

women in draped gowns and peasant jewelry; stout, bearded soldiers with daggers

at their belts, and a certain warmly exotic way of mountain life. A smattering

of nineteenth-century “Circassian” branded products promised women they could

achieve Circassian beauty in their own home: hair dye to turn light-colored

tresses into a “soft, glossy & natural” brown or black, Circassian fabric

to achieve the right gauzy look, and various skin products promising “that

whiteness, transparency and color so highly prized by all civilized nations”.

The endorsement of “the elite of our cities, the Opera, [and] the stage” was

supposed to be reassuring, but the promise of removing freckles, acne, sunburn,

“Moth”, and roughness suggests such lotions were little more than a chemical

belt sander for one’s face.

Circassia

was more than the rugged, simplistic paradise one might have imagined from

cosmetics or travelogues. The target of invasion and ethnic cleansing

throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as Russia and Ottoman Turkey

encroached by land and sea, Circassia was invaded during the Russian conquest

of the Caucasus and formally placed under Russian control following the end of

the Crimean War in 1856. During this period (just before Barnum’s Caucasian

beauty appeared on the scene), the Russian Empire carried out systematic murder

and expulsion against the region’s predominantly Muslim communities. By the middle

1860s, the remaining population was largely and forcibly evacuated to the

Ottoman Empire, where overcrowding, price-gouging, and enslavement were

enduring risks for Circassian refugees.

There

was, concurrently, a mid-century Western fascination with melodramatic

narratives of white slavery, popular on both sides of the Atlantic in the

mid-nineteenth century. Art and drama explored the horror-movie allure of brute

men trafficking in the doom of innocent, blushing virgins (suffice it to say

that the reality of human trafficking was far broader, harsher, and less

discriminating). In the U.S., this manifested in many ways. The sculptor Hiram

Powers’ Greek Slave, a statue of a nude woman chained at the wrists by Turkish

captors, was adopted as an emblem by abolitionists and seen on tour by more

than one hundred thousand Americans in the 1840s. Race and slavery were

explored in plays like Dion Boucicault’s The Octoroon, the 1859 story of a

young southern white woman whose marriage plans are thwarted when it is

revealed that her mother is one of the plantation’s enslaved workers, and who,

despite passing for white, is then put up for sale with the assets of her

father’s estate. (British audiences got a happy ending, but in American

performances the girl commits suicide, avoiding even staged approval of mixed

marriage.) These audiences liked to raise their collective heart-rate in a safe

environment, playing out histrionic fears of subjugation and integration

through entertainment.

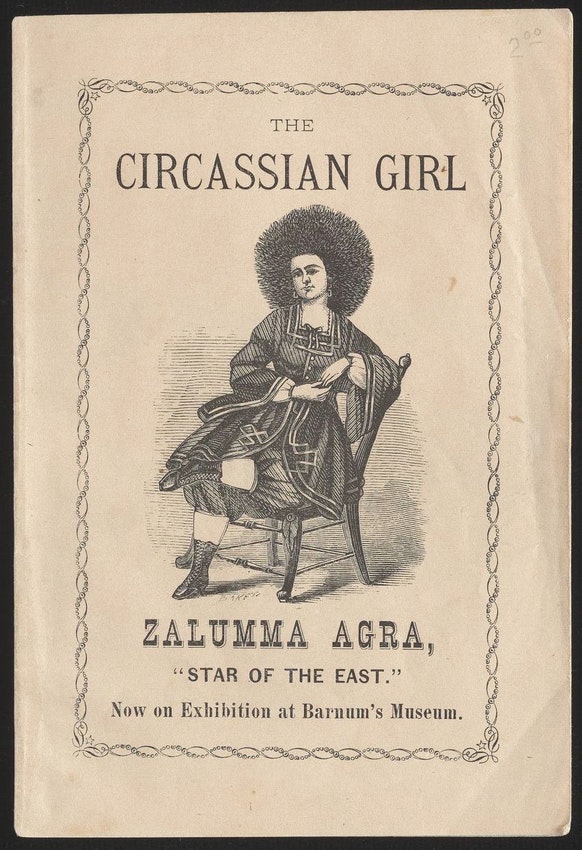

It was

against this backdrop that, in 1865, P. T. Barnum introduced American Museum

patrons to Zalumma Agra, the “Star of the East”, the first “Circassian beauty”.

Her face framed in a halo of frizzy hair, this alluring young lady appeared in

levees at the American Museum dressed in a trimmed, three-quarter-length dress

with blousy sleeves, a swath of stocking visible above her mid-calf boots. She

occasionally completed the outfit with a sash of luxurious fabric or a

moon-shaped headdress.

A

biographical pamphlet sold to patrons laid out the story of Agra’s childhood

flight from Russian incursion into her native land, and how that path somehow

brought a woman who claimed royal descent to the sort of New York entertainment

venue that also offered pet taxidermy. Agra was said to have been orphaned by

invaders as a child, and discovered by John Greenwood Jr, Barnum’s right-hand

man, on the streets of Constantinople among masses of refugees. “Her marvellous

beauty and pleasant, intelligent manners at once arrested his attention”,

declared the nameless pamphlet author, “while the extraordinary peculiarity of

her hair challenged his interest and his admiration”.

Greenwood,

captivated by the child and hoping to save her from “the beautiful but ignorant

habitat of a pagan’s harem”, negotiated with the girl’s friends and Turkish authorities

to become her guardian, providing tutoring and accommodations to help her grow

into the “thorough and lavishly educated woman” of eighteen then entertaining

at the American Museum. No one was especially encouraged to inquire in further

detail: Agra’s promoters insisted that, since she had left Circassia as a

child, her homeland existed in her mind as “an imperfect and confused dream”,

and she remembered little of her native language.

As one

might expect, the true story was a bit different, and Agra’s promoters took

full advantage of the interpretive space afforded by imperfect details and

confused dreams. John Greenwood had indeed gone east on a scouting trip in

1864, looking to engage an allegedly horned woman. Greenwood found no one worth

exhibiting, and Barnum instructed him via letter to instead look for “a

beautiful Circassian girl if you can get one”. Barnum, in his autobiography,

says little about what followed, except that Greenwood disguised himself as a

slave-buyer and saw “a large number of Circassian girls and women” in

Constantinople. In private correspondence Barnum was more frank about his

willingness to conveniently ignore the evils of the Ottoman slave economy if it

got him a guaranteed hit: “If you can also buy a beautiful Circassian woman”,

he wrote Greenwood, “do so if you think best; or if you can hire one or two at

reasonable prices, do so if you think they are pretty and will pass for

Circassian slaves . . . if she is beautiful, then she may take in Paris or in

London or probably both. But look out that in Paris they don't try the law and

set her free. It must be understood she is free”. The Circassian beauty made

her debut not long afterward, presented as the result of Greenwood’s

expedition. An alternative origin story, uncovered by the disability scholar

Robert Bogdan in his 1988 book Freak Show, offers an explanation that seems far

more likely for the sort of Circassian lady who spoke in a perfect American

accent, and the sort of showman who was not exactly known for his infinite

patience: Greenwood came back empty-handed, and the American Museum (not

wanting to waste a good story) decided to cast a “Circassian” beauty from the

local talent roster.

That the

woman in question had distinctively abundant hair was, as best the historical

record can tell us, initially incidental. As the act grew in popularity,

though, her style created a stereotype for all subsequent women performing as

Circassian beauties (completely divorced from the style of actual Circassians):

frizzy hairdos, the larger the better. Whether or not “Circassian” performers

were originally from the Black Sea region was generally irrelevant, and in

truth the role was a character fiction, played by women — often lower class and

recently arrived to the U.S. from Europe — who washed their hair in beer to

achieve the desired look. Soon enough, a succession of women appeared in public

performance as Circassian beauties, with a carefully crafted foreign allure and

a particular visual script: voluminous Afro-like hair, exoticized peasant

costumes, a bit of skin (more as time went on: dresses eventually gave way to

ruffly shorts and tights), and a name that usually began with the letter “Z” —

Zula Zeleah, Zoe Zobedia, Zuruby Hannum, and Zobeide Luti, to name a few.

The

Circassian character — and she was a character, to be sure, as much as any

dramatic role — was presented as the pinnacle of beauty and evolution. But this

ideal white woman was also an unfamiliar curiosity from a foreign culture with

hair that connoted exoticism and minstrelsy. We have no idea if Barnum retained

the hairstyle part of the act on purpose, in a direct effort to imitate Black

hair or parody Black identity; nevertheless, the retention irretrievably linked

the Circassian Beauty with the racist associations and biases circulating in

American society. This entertainment effectively took the prior vogue of

Circassian beauty, which had far more conventional aspirations (selling glossy

brunette hair dye and flowery journalism), and added a thick layer of

Circassian whiteness. In using large textured hairstyles and suggestive poses,

Circassian beauties called forth cultural myths about promiscuity, tribalism,

and social worthiness, borrowing qualities from other racist stereotypes, like

the “Jezebel”, a lascivious seductress. “The ethnic kink”, wrote author Charles

D. Martin in The White African American Body, referencing the Circassian

beauty’s hair, “supplied a visible bridge between the normalized, exalted

whiteness that conferred citizenship and the distinguishing marks of racial difference

that facilitated slavery. The emancipated white body still bore the evidence of

its dark-bodied captivity.” The idea of white beauty relying on non-white

stereotypes — that whiteness, taken to its archetypal extreme, blends Black and

Caucasian features — is perhaps the strangest, most puzzling, and cunning facet

of the Circassian beauty act.

Within the sideshow ecosystem, the Circassian

beauty was more complex than her colleagues. She was not celebrated in her

individual identity like Anna Swan the giantess, nor was she exaggerated into

racialized or ableist inhumanity like many “ethnic curiosities” of the day.

Audiences could view her as morally upright, having escaped the harem for a

Western lifestyle, but still gasp at her past proximity to prostitution and

“pagan” sensuality. Rescued from a life of indentured, sexual slavery (so the

story went), the woman began anew in the United States at the very moment that

this nation, built on chattel slavery, passed the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.

At the

time Barnum debuted his Circassian beauty, it was an entertainment consistent

with a general culture of racial anxiety. In show business, as in science and

in the explosive political sphere, matters of race held a particular charge. In

the middle 1860s, the increasingly violent politics of abolition and its

detractors added a menacing edge to life in New York, which, despite its

northern location, was conspicuously unfriendly toward President Lincoln and

his refusal to make peace with the South. New York mayor Fernando Wood had

suggested in 1861 that the city secede from both New York state and the Union —

a “venal and corrupt master” — entirely. That did not happen, but New Yorkers

rioted in reaction to the federal draft for four days in July 1863, and

Confederate press threatening to burn the city in response to Union offensives

in the South assured readers that “The men to execute the work [raze New York]

are already there”. The city remained so staunchly hostile to Lincoln

administration policy and abolitionism that Union general Benjamin Butler,

nicknamed “The Beast”, was posted to the city along with thousands of soldiers

to ensure peace during the 1864 Presidential election. And all manner of

then-current arts and “sciences”, from phrenology to miscegenation theory,

attempted to explain and reinforce a scheme of racial hierarchy that overlaid

itself onto warring political agendas.

The

public’s guilty fascination with white slavery narratives only boosted the

Circassian beauty’s popularity, and further crowded the inseparable braid of

historical concerns and contemporary biases involved in her exhibition. No one

interpretation seems sufficient, yet all, taken together, do not arrive at

clarity. In addition to the politics of American slavery and the pervasive

social fear of miscegenation, there was the romanticized supposition that

enslaved harem women were engaged in a “luxurious and mindless” state of posh

lounges, scanty clothing, and day after day of idle indulgence, while

Circassian men had to be rough primitives who “value their women less than

their stirrups” despite the women’s legendary beauty. These stories invoke questions

about Orientalism, making enemies of foreign sultans, and showing Circassian

ladies as subjects in need of colonizing influence; and they glorify

non-intellectual domesticity in a thumbs-up to conventional Victorian-era

womanhood. This entertainment was a mixtape that suited the current mood:

enough truth about Circassian slavery to ground the story in feasibility;

enough of a racialized visual language to invoke race and slavery in American

politics; Orientalist harem stories to justify white colonialist hierarchy; and

re-education narratives to reinforce female subordination and norms of conduct.

Barnum’s

American Museum was an arena in which such questions regarding performance,

social structure, and racial status could be considered. This sort of museum

model, which purported to show the wonders of the wider world to a mass of

people who did not have the ability to travel, was helpful insofar as it

democratized access to knowledge (the American Museum drew crowds on par with

modern Disneyland); but it was a highly curated presentation, in which people

and groups could all too easily be fetishized or tokenized. And while Barnum’s

reputation as an exploitative sideshow huckster is not entirely deserved — he

was a reputable employer, paid well, and insisted his employees were “living

wonders” rather than freaks — race undeniably mattered in how performers of

color were presented to the paying public. The same P. T. Barnum who in 1865

would speak before the Connecticut legislature to lobby for Black voting rights

nonetheless continued to rely on the profitable prevalence of lazy stereotype

and exoticism in paid entertainment. (For Barnum, as with many prominent men of

his era, anti-slavery did not necessarily mean pro-equality, and his

unwillingness to alienate any paying customer meant that he avoided taking

moral stances on the stage that were justly called for.) Zalumma Agra and other

Circassian beauties would have been exhibited under the same roof as the likes

of the Lucasie family who had albinism, the “Living Chinese Family”, or “What

Is It?”, a piece of racist, pseudoscientific theater in which a Black man

played the role of a supposed “missing link” between apes and humans. All of

this assumed and proclaimed a certain white social standard, and allowed

viewers to feel comfortably superior to the humans who were, in their eyes,

reduced to “curiosities” on display.

The

stereotype of the Circassian beauty continued in sideshows for quite some time.

Dime museums and circuses claimed to have the original Zalumma Agra on display

for decades, well past the point of feasibility (not that anyone seemed to

mind). In the 1880s, when Barnum was enjoying later-life fame as a circus

entrepreneur, his “Greatest Show on Earth” typically included a Circassian

woman in its sideshow, and one of the most famous — Zoe Meleke — offered a

pamphlet that told the same life story that had accompanied Zalumma Agra

decades earlier. Into the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, as the

Circassian story had less resonance for audiences, performers often doubled as

similarly exoticized snake-charmer acts, or displayed their hair as a curiosity

without the romance of a Black Sea origin story: this was the case with the

likes of Mademoiselle Ivy, the “Moss-Haired Girl”, and Zumigo, played by a

Black performer. While the latter character’s name and hairstyle conjured her

“Caucasian” predecessors, Zumigo was billed as an Egyptian, swapping peasant

costumes for fancy dresses and fringed leotards.

The

legacy of the Circassian beauty endures, beginning with the fact that the word

“Caucasian” is now so common in use as to be completely divorced from its

origins. Today, the question of race as performance has further crossed the

permeable barrier between the stage and the outside world — the Circassian

woman, after all, relied not only on prevalent bias but on the suspension of

disbelief that was P. T. Barnum’s stock-in-trade. More recent controversies

over assumed racial identity, from Rachel Dolezal to Jessica Krug, Hache

Carrillo, and Andrea Smith, have been carried out in the public sphere, where

there is no ticket booth or stage curtain to signal a space of malleable truth,

and where repercussions touch more than an audience or performer. Circassian

beauties may seem like a distant relic of the Barnum era, their popularity only

hinted at from the quiet of a cabinet card or carte-de-visite photograph today,

but, in demonstrating the pitfalls of reducing any experience to a performed

stereotype, they still contribute to our ongoing dialogue around race,

community, and identity.

Circassian

Beauty in the American Sideshow. By Betsy Golden Kellem. The Public Domain Review, September 16, 2021.

No comments:

Post a Comment