The

Drowned Children

You see,

they have no judgment.

So it is

natural that they should drown,

first

the ice taking them in

and

then, all winter, their wool scarves

floating

behind them as they sink

until at

last they are quiet.

And the

pond lifts them in its manifold dark arms.

But

death must come to them differently,

so close

to the beginning.

As

though they had always been

blind

and weightless. Therefore

the rest

is dreamed, the lamp,

the good

white cloth that covered the table,

their

bodies.

And yet

they hear the names they used

like

lures slipping over the pond:

What are you waiting for

come home, come home, lost

in the waters, blue and permanent.

Mock

Orange

It is

not the moon, I tell you.

It is

these flowers

lighting

the yard.

I hate

them.

I hate

them as I hate sex,

the

man’s mouth

sealing

my mouth, the man’s

paralyzing

body—

and the

cry that always escapes,

the low,

humiliating

premise

of union—

In my

mind tonight

I hear

the question and pursuing answer

fused in

one sound

that

mounts and mounts and then

is split

into the old selves,

the

tired antagonisms. Do you see?

We were

made fools of.

And the

scent of mock orange

drifts

through the window.

How can

I rest?

How can

I be content

when

there is still

that

odor in the world?

The Pond

Night

covers the pond with its wing.

Under

the ringed moon I can make out

your

face swimming among minnows and the small

echoing

stars. In the night air

the

surface of the pond is metal.

Within,

your eyes are open. They contain

a memory

I recognize, as though

we had

been children together. Our ponies

grazed

on the hill, they were gray

with

white markings. Now they graze

with the

dead who wait

like

children under their granite breastplates,

lucid

and helpless:

The

hills are far away. They rise up

blacker

than childhood.

What do

you think of, lying so quietly

by the

water? When you look that way I want

to touch

you, but do not, seeing

as in

another life we were of the same blood.

The Fear

of Burial

In the

empty field, in the morning,

the body

waits to be claimed.

The

spirit sits beside it, on a small rock--

nothing

comes to give it form again.

Think of

the body's loneliness.

At night

pacing the sheared field,

its

shadow buckled tightly around.

Such a

long journey.

And

already the remote, trembling lights of the village

not

pausing for it as they scan the rows.

How far

away they seem,

the

wooden doors, the bread and milk

laid

like weights on the table.

Lamentations

1. The

Logos

They

were both still,

the

woman mournful, the man

branching

into her body.

But God

was watching.

They

felt his gold eye

projecting

flowers on the landscape.

Who knew

what He wanted?

He was

God, and a monster.

So they

waited. And the world

filled

with His radiance,

as

though He wanted to be understood.

Far

away, in the void that He had shaped,

he

turned to his angels.

2.

Nocturne

A forest

rose from the earth.

O

pitiful, so needing

God’s

furious love—

Together

they were beasts.

They lay

in the fixed

dusk of

His negligence;

from the

hills, wolves came, mechanically

drawn to

their human warmth,

their

panic.

Then the

angels saw

how He

divided them:

the man,

the woman, and the woman’s body.

Above

the churned reeds, the leaves let go

a slow

moan of silver.

3. The

Covenant

Out of

fear, they built a dwelling place.

But a

child grew between them

as they

slept, as they tried

to feed

themselves.

They set

it on a pile of leaves,

the

small discarded body

wrapped

in the clean skin

of an

animal. Against the black sky

they saw

the massive argument of light.

Sometimes

it woke. As it reached its hands

they

understood they were the mother and father,

there

was no authority above them.

4. The

Clearing

Gradually,

over many years,

the fur

disappeared from their bodies

until

they stood in the bright light

strange

to one another.

Nothing

was as before.

Their

hands trembled, seeking

the

familiar.

Nor

could they keep their eyes

from the

white flesh

on which

wounds would show clearly

like

words on a page.

And from

the meaningless browns and greens

at last

God arose, His great shadow

darkening

the sleeping bodies of His children,

and

leapt into heaven.

How

beautiful it must have been,

the

earth, that first time

seen

from the air.

Siren

I became

a criminal when I fell in love.

Before

that I was a waitress.

I didn't

want to go to Chicago with you.

I wanted

to marry you, I wanted

Your

wife to suffer.

I wanted

her life to be like a play

In which

all the parts are sad parts.

Does a

good person

Think

this way? I deserve

Credit

for my courage--

I sat in

the dark on your front porch.

Everything

was clear to me:

If your

wife wouldn't let you go

That

proved she didn't love you.

If she

loved you

Wouldn't

she want you to be happy?

I think

now

If I

felt less I would be

A better

person. I was

A good

waitress.

I could

carry eight drinks.

I used

to tell you my dreams.

Last

night I saw a woman sitting in a dark bus--

In the

dream, she's weeping, the bus she's on

Is

moving away. With one hand

She's

waving; the other strokes

An egg

carton full of babies.

The

dream doesn't rescue the maiden.

Celestial

Music

I have a

friend who still believes in heaven.

Not a

stupid person, yet with all she knows, she literally talks to God.

She

thinks someone listens in heaven.

On earth

she's unusually competent.

Brave

too, able to face unpleasantness.

We found

a caterpillar dying in the dirt, greedy ants crawling over it.

I'm

always moved by disaster, always eager to oppose vitality

But

timid also, quick to shut my eyes.

Whereas

my friend was able to watch, to let events play out

According

to nature. For my sake she intervened

Brushing

a few ants off the torn thing, and set it down

Across

the road.

My

friend says I shut my eyes to God, that nothing else explains

My

aversion to reality. She says I'm like the child who

Buries

her head in the pillow

So as

not to see, the child who tells herself

That

light causes sadness-

My

friend is like the mother. Patient, urging me

To wake

up an adult like herself, a courageous person-

In my

dreams, my friend reproaches me. We're walking

On the

same road, except it's winter now;

She's

telling me that when you love the world you hear celestial music:

Look up,

she says. When I look up, nothing.

Only

clouds, snow, a white business in the trees

Like

brides leaping to a great height-

Then I'm

afraid for her; I see her

Caught

in a net deliberately cast over the earth-

In

reality, we sit by the side of the road, watching the sun set;

From

time to time, the silence pierced by a birdcall.

It's

this moment we're trying to explain, the fact

That

we're at ease with death, with solitude.

My friend

draws a circle in the dirt; inside, the caterpillar doesn't move.

She's

always trying to make something whole, something beautiful, an image

Capable

of life apart from her.

We're

very quiet. It's peaceful sitting here, not speaking, The composition

Fixed,

the road turning suddenly dark, the air

Going

cool, here and there the rocks shining and glittering-

It's

this stillness we both love.

The love

of form is a love of endings.

End of

Winter

Over the

still world, a bird calls

waking

solitary among black boughs.

You

wanted to be born; I let you be born.

When has

my grief ever gotten

in the

way of your pleasure?

Plunging

ahead

into the

dark and light at the same time

eager

for sensation

as

though you were some new thing, wanting

to

express yourselves

all

brilliance, all vivacity

never

thinking

this

would cost you anything,

never

imagining the sound of my voice

as

anything but part of you—

you

won't hear it in the other world,

not

clearly again,

not in

birdcall or human cry,

not the

clear sound, only

persistent

echoing

in all

sound that means good-bye, good-bye—

the one

continuous line

that

binds us to each other.

Vespers

[In your extended absence, you permit me]

In your

extended absence, you permit me

use of

earth, anticipating

some

return on investment. I must report

failure

in my assignment, principally

regarding

the tomato plants.

I think

I should not be encouraged to grow

tomatoes.

Or, if I am, you should withhold

the

heavy rains, the cold nights that come

so often

here, while other regions get

twelve

weeks of summer. All this

belongs

to you: on the other hand,

I

planted the seeds, I watched the first shoots

like

wings tearing the soil, and it was my heart

broken by

the blight, the black spot so quickly

multiplying

in the rows. I doubt

you have

a heart, in our understanding of

that

term. You who do not discriminate

between

the dead and the living, who are, in consequence,

immune

to foreshadowing, you may not know

how much

terror we bear, the spotted leaf,

the red

leaves of the maple falling

even in

August, in early darkness: I am responsible

for

these vines.

The Wild

Iris

At the

end of my suffering

there

was a door.

Hear me

out: that which you call death

I

remember.

Overhead,

noises, branches of the pine shifting.

Then

nothing. The weak sun

flickered

over the dry surface.

It is

terrible to survive

as

consciousness

buried

in the dark earth.

Then it

was over: that which you fear, being

a soul

and unable

to

speak, ending abruptly, the stiff earth

bending

a little. And what I took to be

birds

darting in low shrubs.

You who

do not remember

passage

from the other world

I tell

you I could speak again: whatever

returns

from oblivion returns

to find

a voice:

from the

center of my life came

a great

fountain, deep blue

shadows

on azure sea water.

Anniversary

I said

you could snuggle. That doesn’t mean

your

cold feet all over my dick.

Someone

should teach you how to act in bed.

What I

think is you should

keep

your extremities to yourself.

Look

what you did—

you made

the cat move.

But I didn’t want your hand there.

I wanted your hand here.

You should pay attention to my

feet.

You should picture them

the next time you see a hot fifteen

year old.

Because there’s a lot more where

those feet come from.

Parable

of the Swans

On a

small lake off

the map

of the world, two

swans

lived. As swans,

they

spent eighty percent of the day studying

themselves

in the attentive water and

twenty

percent ministering to the beloved

other.

Thus

their

fame as lovers stems

chiefly

from narcissism, which leaves

so

little leisure for

more

general cruising. But

fate had

other plans: after ten years, they hit

slimy

water; whatever the filth was, it

clung to

the male’s plumage, which turned

instantly

gray; simultaneously,

the true

purpose of his neck’s

flexible

design revealed itself. So much

action

on the flat lake, so much

he’s

missed! Sooner or later in a long

life

together, every couple encounters

some

emergency like this, some

drama

which results

in harm.

This

occurs

for a reason: to test

love and

to demand

fresh

articulation of its complex terms.

So it

came to light that the male and female

flew

under different banners: whereas

the male

believed that love

was what

one felt in one’s heart

the

female believed

love was

what one did. But this is not

a little

story about the male’s

inherent

corruption, using as evidence the swan’s

sleazy

definition of purity. It is

a story

of guile and innocence. For ten years

the

female studied the male; she dallied

when he

slept or when he was

conveniently

absorbed in the water,

while

the spontaneous male

acted

casually, on

the whim

of the moment. On the muddy water

they

bickered awhile, in the fading light,

until

the bickering grew

slowly

abstract, becoming

part of

their song

after a

little longer.

Vita

Nova

You

saved me, you should remember me.

The

spring of the year; young men buying tickets for the ferryboats.

Laughter,

because the air is full of apple blossoms.

When I

woke up, I realized I was capable of the same feeling.

I

remember sounds like that from my childhood,

laughter

for no cause, simply because the world is beautiful,

something

like that.

Lugano.

Tables under the apple trees.

Deckhands

raising and lowering the colored flags.

And by

the lake’s edge, a young man throws his hat into the water;

perhaps

his sweetheart has accepted him.

Crucial

sounds

or gestures like

a track

laid down before the larger themes

and then

unused, buried.

Islands

in the distance. My mother

holding

out a plate of little cakes—

as far

as I remember, changed

in no

detail, the moment

vivid,

intact, having never been

exposed

to light, so that I woke elated, at my age

hungry

for life, utterly confident—

By the

tables, patches of new grass, the pale green

pieced

into the dark existing ground.

Surely

spring has been returned to me, this time

not as a

lover but a messenger of death, yet

it is

still spring, it is still meant tenderly.

The

Empty Glass

I asked

for much; I received much.

I asked

for much; I received little, I received

next to

nothing.

And

between? A few umbrellas opened indoors.

A pair

of shoes by mistake on the kitchen table.

O wrong,

wrong—it was my nature. I was

hard-hearted,

remote. I was

selfish,

rigid to the point of tyranny.

But I

was always that person, even in early childhood.

Small,

dark-haired, dreaded by the other children.

I never

changed. Inside the glass, the abstract

tide of

fortune turned

from

high to low overnight.

Was it

the sea? Responding, maybe,

to

celestial force? To be safe,

I

prayed. I tried to be a better person.

Soon it

seemed to me that what began as terror

and

matured into moral narcissism

might

have become in fact

actual

human growth. Maybe

this is

what my friends meant, taking my hand,

telling

me they understood

the

abuse, the incredible shit I accepted,

implying

(so I once thought) I was a little sick

to give

so much for so little.

Whereas

they meant I was good (clasping my

hand intensely)—

a good

friend and person, not a creature of pathos.

I was

not pathetic! I was writ large,

like a

queen or a saint.

Well, it

all makes for interesting conjecture.

And it

occurs to me that what is crucial is to believe

in

effort, to believe some good will come of simply trying,

a good

completely untainted by the corrupt initiating impulse

to

persuade or seduce—

What are

we without this?

Whirling

in the dark universe,

alone,

afraid, unable to influence fate—

What do

we have really?

Sad

tricks with ladders and shoes,

tricks

with salt, impurely motivated recurring

attempts

to build character.

What do

we have to appease the great forces?

And I

think in the end this was the question

that

destroyed Agamemnon, there on the beach,

the

Greek ships at the ready, the sea

invisible

beyond the serene harbor, the future

lethal,

unstable: he was a fool, thinking

it could

be controlled. He should have said

I have nothing, I am at your mercy.

Mother

and Child

We’re

all dreamers; we don’t know who we are.

Some

machine made us; machine of the world, the constricting family.

Then

back to the world, polished by soft whips.

We

dream; we don’t remember.

Machine

of the family: dark fur, forests of the mother’s body.

Machine

of the mother: white city inside her.

And

before that: earth and water.

Moss

between rocks, pieces of leaves and grass.

And

before, cells in a great darkness.

And

before that, the veiled world.

This is

why you were born: to silence me.

Cells of

my mother and father, it is your turn

to be

pivotal, to be the masterpiece.

I

improvised; I never remembered.

Now it’s

your turn to be driven;

you’re

the one who demands to know:

Why do I

suffer? Why am I ignorant?

Cells in

a great darkness. Some machine made us;

it is

your turn to address it, to go back asking

what am

I for? What am I for?

A Village

Life

The

death and uncertainty that await me

as they

await all men, the shadows evaluating me

because

it can take time to destroy a human being,

the

element of suspense

needs to

be preserved—

On

Sundays I walk my neighbor’s dog

so she

can go to church to pray for her sick mother.

The dog

waits for me in the doorway. Summer and winter

we walk

the same road, early morning, at the base of the escarpment.

Sometimes

the dog gets away from me—for a moment or two,

I can’t

see him behind some trees. He’s very proud of this,

this

trick he brings out occasionally, and gives up again

as a

favor to me—

Afterward,

I go back to my house to gather firewood.

I keep

in my mind images from each walk:

monarda

growing by the roadside;

in early

spring, the dog chasing the little gray mice

so for a

while it seems possible

not to

think of the hold of the body weakening, the ratio

of the

body to the void shifting,

and the

prayers becoming prayers for the dead.

Midday,

the church bells finished. Light in excess:

still,

fog blankets the meadow, so you can’t see

the

mountain in the distance, covered with snow and ice.

When it

appears again, my neighbor thinks

her

prayers are answered. So much light she can’t control her happiness—

it has

to burst out in language. Hello, she yells, as though

that is

her best translation.

She

believes in the Virgin the way I believe in the mountain,

though

in one case the fog never lifts.

But each

person stores his hope in a different place.

I make

my soup, I pour my glass of wine.

I’m

tense, like a child approaching adolescence.

Soon it

will be decided for certain what you are,

one

thing, a boy or girl. Not both any longer.

And the

child thinks: I want to have a say in what happens.

But the

child has no say whatsoever.

When I

was a child, I did not foresee this.

Later,

the sun sets, the shadows gather,

rustling

the low bushes like animals just awake for the night.

Inside,

there’s only firelight. It fades slowly;

now only

the heaviest wood’s still

flickering

across the shelves of instruments.

I hear

music coming from them sometimes,

even

locked in their cases.

When I

was a bird, I believed I would be a man.

That’s

the flute. And the horn answers,

When I

was a man, I cried out to be a bird.

Then the

music vanishes. And the secret it confides in me

vanishes

also.

In the

window, the moon is hanging over the earth,

meaningless

but full of messages.

It’s dead,

it’s always been dead,

but it

pretends to be something else,

burning

like a star, and convincingly, so that you feel sometimes

it could

actually make something grow on earth.

If

there’s an image of the soul, I think that’s what it is.

I move

through the dark as though it were natural to me,

as

though I were already a factor in it.

Tranquil

and still, the day dawns.

On

market day, I go to the market with my lettuces.

A

Sharply Worded Silence

Let me

tell you something, said the old woman.

We were

sitting, facing each other,

in the

park at ___, a city famous for its wooden toys.

At the

time, I had run away from a sad love affair,

and as a

kind of penance or self punishment, I was working

at a

factory, carving by hand the tiny hands and feet.

The park

was my consolation, particularly in the quiet hours

after

sunset, when it was often abandoned,

But on

this evening, when I entered what was called the Contessa’s Garden,

I saw

that someone had preceded me. It strikes me now

I could

have gone ahead, but I had been

set on

this destination; all day I had been thinking of the cherry trees

with

which the glade was planted, whose time of blossoming had nearly ended.

We sat

in silence. Dusk was falling,

and with

it came a feeling of enclosure

as in a

train cabin.

When I

was young, she said, I liked walking the garden path at twilight

and if

the path was long enough I would see the moon rise.

That was

for me the great pleasure: not sex, not food, not worldly amusement.

I

preferred the moon’s rising, and sometimes I would hear,

at the

same moment, the sublime notes of the final ensemble

of The

Marriage of Figaro. Where did the music come from?

I never

knew.

Because

it is the nature of garden paths

to be

circular, each night, after my wanderings,

I would

find myself at my front door, staring at it,

barely

able to make out, in darkness, the glittering knob.

It was,

she said, a great discovery, albeit my real life.

But

certain nights, she said, the moon was barely visible through the clouds

and the

music never started. A night of pure discouragement.

And

still the next night I would begin again, and often all would be well.

I could

think of nothing to say. This story, so pointless as I write it out,

was in

fact interrupted at every stage with trance-like pauses

and

prolonged intermissions, so that by this time night had started.

Ah the

capacious night, the night

so eager

to accommodate strange perceptions. I felt that some important secret

was

about to be entrusted to me, as a torch is passed

from one

hand to another in a relay.

My

sincere apologies, she said.

I had

mistaken you for one of my friends.

And she

gestured toward the statues we sat among,

heroic

men, self-sacrificing saintly women

holding

granite babies to their breasts.

Not

changeable, she said, like human beings.

I gave

up on them, she said.

But I

never lost my taste for circular voyages.

Correct

me if I’m wrong.

Above

our heads, the cherry blossoms had begun

to

loosen in the night sky, or maybe the stars were drifting,

drifting

and falling apart, and where they landed

new

worlds would form.

Soon

afterward I returned to my native city

and was

reunited with my former lover.

And yet

increasingly my mind returned to this incident,

studying

it from all perspectives, each year more intensely convinced,

despite

the absence of evidence, that it contained some secret.

I

concluded finally that whatever message there might have been

was not

contained in speech—so, I realized, my mother used to speak to me,

her

sharply worded silences cautioning me and chastizing me—

and it

seemed to me I had not only returned to my lover

but was

now returning to the Contessa’s Garden

in which

the cherry trees were still blooming

like a

pilgrim seeking expiation and forgiveness,

so I

assumed there would be, at some point,

a door

with a glittering knob,

but when

this would happen and where I had no idea.

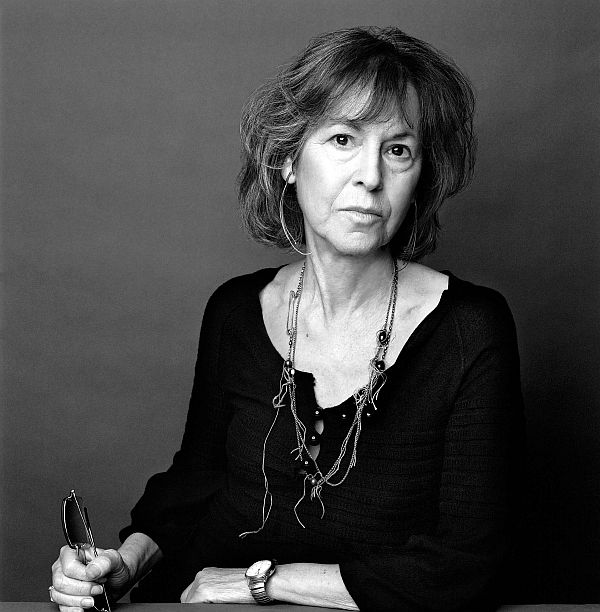

more information on Louise Glück :

Louise

Glück, a former Poet Laureate of the United States, is the author of over a

dozen books of poetry including Faithful and Virtuous Night (winner of the

National Book Award for Poetry) and her recent anthology, Poems: 1962-2012.

Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Hass has called her “one of the purest and most

accomplished lyric poets now writing.”

Glück

taught at Williams College for 20 years and is currently Rosenkranz

writer-in-residence at Yale University. She is a member of the American Academy

of Arts and Letters, and in 1999 was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of

American Poets. Her numerous books of poetry include A Village Life (2009), The

Seven Ages (2001), and The Wild Iris (1992), for which she received the

Pulitzer Prize. Louise Glück says of writing, “[It] is not decanting of

personality. The truth, on the page, need not have been lived. It is, instead,

all that can be envisioned.”

Louise

Glück with Peter Streckfus, Conversation.

Recorded at the Lensic Theater in Santa Fe, New Mexico on May 11, 2016. This

was a Lannan Literary event.

Louise Glück,

is introduced by Peter Streckfus and

then read from her work.

A Lannan Literary event.

Stand-Up

Vampire. By Gillian White. London Review of Books , September 26, 2013.

Acquainted

With the Dark. By Peter Campion. New York Times , September 26, 2014

No comments:

Post a Comment