“My only consolation’s that I’m me—vivacious, dynamic, single, and a queer,” quips Bongi Perez, the intrepid antiheroine of Valerie Solanas’s Up Your Ass. Written between 1962 and 1965, the play features a wisecracking masc lesbian panhandler and sex worker who sounds a lot like the writer herself. Notorious for shooting Andy Warhol and his associate Mario Amaya in 1968, Solanas’s best-known text is her SCUM Manifesto (1967), outlining a program of male elimination. But it was Up Your Ass, a lesser-known dramatic work, that lay at the heart of her conflict with Warhol. Until now, the bawdy and rollicking play has never been published by a major press. This month, it appears via Sternberg’s sub-imprint Montana.

It’s an apt time for the release of Up Your Ass, an absurdist one-act poking fun at post-Pill, pre-Roe 1960s sexual politics from all directions. Although SCUM Manifesto became a fringe classic, many feminists have debated its value as a humorous work vs. a deadly serious homicidal screed. A contrarian who alienated major figures from the women’s liberation movement, Solanas’s famous combativeness led critics to distance themselves from her work. But interest in Solanas has intensified over the last decade, due in part to new scholarship. (In 2014, for instance, Breanne Fahs published an excellently researched biography of the writer through the Feminist Press.) The US’s extreme rightward shift has also cast rageful radicals like Solanas in a more sympathetic light. As the rights of queer and trans people, sex workers, and people capable of pregnancy become further endangered, Solanas’s ribald play fascinates as a relic of taboo-busting sexual content, if not always the most cogent attack on the patriarchal status quo.

Up Your Ass has arguably enjoyed its widest pop-cultural visibility via Mary Harron’s 1996 biopic I Shot Andy Warhol. Starring a young Lili Taylor, the film follows the aspiring writer as she infiltrates the Pop artist’s social circle in the hopes that he will produce her play. Between first sending her script to Warhol in 1965 and shooting him three years later, Solanas wandered in and out of the Factory scene. When she was particularly hard up for cash, Warhol paid her a measly $25 to play a lesbian character in his 1967 film I, a Man. In an improvised scene in a stairwell, Solanas shifts between light flirting and sparring with Tom Baker before turning down his advances. The tension in I Shot Andy Warhol escalates as Solanas, after signing a dubious contract with publisher Maurice Girodias, enters a psychosis fueled by public humiliation and paranoia over the ownership of her works. She attempts to assassinate Warhol and his studio staff after claiming that he lost the “only” copy of her play. In the ensuing decades, there’s been a mistaken conflation between Solanas’s life and art: Up Your Ass as a forgotten dry run of the SCUM Manifesto, SCUM as a manual for deadly violence against men, and Solanas’s attack on Warhol. Like all events involving Valerie Solanas, the reality is more complicated.

Warhol did lose his copy of Solanas’s manuscript, which was later recovered in a silver-painted trunk belonging to Billy Name. It is untrue, however, that it was Solanas’s only copy. The writer had high ambitions for the play, filing multiple copyrights for the manuscript, staging small readings, and producing mimeographs of it for sale. As the radical feminist activist Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz recalled, Solanas spoke unceasingly about the play during her psychiatric holds and incarceration following the shooting. In the early 1970s, she performed a one-woman version of it while imprisoned for first-degree assault at Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane.

Despite Solanas’s insistence on its artistic significance, the play was eclipsed by her strident SCUM Manifesto, published by Girodias’s Olympia Press immediately after her arrest. In fact, Up Your Ass has only been staged once by a professional company. In 2000, George Coates Performance Works mounted a version with an all-female cast in San Francisco, just blocks from the SRO where Solanas died alone, a dozen years earlier, at the age of fifty-two. In 2001, the production saw a short run at New York’s P.S. 122. “Far from being a museum piece, ‘Up Your Ass’ is a clarion call,” wrote one reviewer. The show was heralded at the time for its forward-thinking take on genderbending and homicidal frustration with male chauvinism. Today, it stands out as much for its punkish irreverence—Solanas spares no one from her main character’s acid tongue.

Up Your Ass follows Bongi Perez, Solanas’s stand-in, on an average day hustling in the streets of “a large American city.” (Solanas wrote an early draft while living in Berkeley, California, and revised it in New York.) Full of clapbacks and one-liners, the script celebrates the fine art of gutter-talk while offering a parodic send-up of misogyny during the swinging ’60s. Over the course of Bongi’s wanderings, she catcalls women (“You got a twat by Dior?”); shoots the breeze with two single men (Black Cat and White Cat) about pickup strategies; hustles a john for dinner before giving him a quick hand job in an alley; and engages in banter with two drag queens (“Do you know what I’d like more than anything in the world to be?” one muses. “A Lesbian. Then I could be the cake and eat it too”). Bongi then meets Ginger, a demented Helen Gurley Brown type who brings her own turd to a dinner party (“Everybody knows that men have much more respect for women who’re good at lapping up shit,” Ginger says), and her faux-intellectual colleague Russell, whom Bongi cajoles into screwing behind a bush just minutes after he declares her a “desexed monstrosity.” As an absurdist palate cleanser, Solanas shifts the scene to a Creative Homemaking class. There, an instructor advises aspiring wives to integrate fucking into domestic chores—by ramming a soaped-up bottle brush up one’s husband’s ass, recalling the play’s titular expletive. In Bongi’s final encounter, our protagonist befriends a bicurious housewife who murders her penis-obsessed toddler. The grand finale shows the pair walking off into the proverbial sunset, aggressively propositioning women together.

The manuscript’s épater la bourgeoisie sensibility, shot through with clichés about race and sexuality, places it squarely in the twentieth century. But the text also outlines a space of genderqueer possibility that wouldn’t be theorized for years, advocates for sex workers’ rights, and sketches the dark future of reproductive technology through allusions to biological determinism. A line can be traced directly from Bongi’s offhanded political musings—“Maybe being president wouldn’t be such a bad idea . . . I could eliminate the money system, and let the machines do all the work”—to SCUM’s opening sentence, which urges “civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females” to “overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and destroy the male sex.” Just as importantly, Bongi expresses a desire that Solanas, who claimed to be asexual, often hid in her public life. The fictional character longs for “real lowdown, funky broads, nasty, bitchy hotshots, the kind that when she enters a room it’s like a blinding flash.” Such heated, desperate attempts at communicating want—in tonally mischievous dialogue that slides between screwball comedy and apocalyptic tirade—crackle throughout Solanas’s script.

Up Your Ass is fascinating, but is it feminist? In Andrea Long Chu’s Females, (2019) her gender-transition-memoir-cum-theoretical-provocation, the same question is posed, but turned inside out. Chu writes that “one could be forgiven for wondering if Solanas’s art, not unlike that of the male artists she despises (and occasionally shot), might have represented its own kind of attempt to repress the very femaleness she hoped to unleash, like a biological weapon, upon the world.” The “always selfish, always cool” vision of femaleness that Solanas laid out in SCUM simply reversed the traditional poles of misogyny. Chu, for her part, embraces Solanas as an avatar of the self-negation she argues is intrinsic to the female condition. “Everyone is female,” Chu declares, “and everyone hates it.”

Up Your Ass reveals Solanas as an equal-opportunity roaster, a role that places her outside of contemporary feminism’s tendency toward self-examination. Rather than shared vulnerability, this sexual comedy is shot through with a tart flavor of camp able to deflect earnest political criticisms directed at the author. Solanas takes aim at the sexual expectations of placed on “groovy,” liberated-but-docile chicks. (In SCUM, she would later damningly term these women “Daddy’s Girls.”) The reader can sense a tension in the play, Solanas knotting her rage into a tightly coiled spring, ready to release at any target that gets in her way—as it did, appallingly, at a fellow queer artist that she once viewed as her potential producer. But we also glimpse traces of Solanas that are more complex and contradictory than her manifesto, or her attempted murders, might suggest. As the old saying goes, women’s greatest fear is that men will kill them, while men’s greatest fear is that women will laugh at them. Rather than programmatic gendercide, her play offers the chance to laugh with her at the grotesqueries of a patriarchy that enmeshes and implicates us all.

Scum as you are : The furious comedy of Valerie Solanas / By Wendy Vogel. Artforum, August 22, 2022

Violent

and corrosively humorous, Dans Ton Cul is a play written in the 1960s by

Valérie Solanas. A short and powerful text by a radical author ahead of her

time, to discover urgently today.

It is often presented for two feats of arms: the publication of SCUM Manifesto in 1967, feminist firebrand and misandre and the attempted assassination of Andy Warhol the following year. Valerie Solanas was radical feminist figure born in 1936 and died in 1988, is again highlighted through the publication in May 2022 and for the first time in France of In Your Ass. This play was translated in France by Wendy Delorme and published by Éditions Fayardin the 1001 Nights collection.

An opportunity to see that the anger of Valérie Solanas is still alive, that his verve still hits the mark, and that his denunciation of male domination and capitalism finds still resonates with feminists today.

How In Your Ass Almost Never Came to Be

In Your Ass (in English Up Your Ass), it is a work of around thirty pages, which Valérie Solanas took three years to write. Claimed lesbian, she then lives in New York, tries to become a writer and earns her living by prostituting herself.

His play almost remained lost in limbo : when in 1967, Valérie Solanas presented her manuscript to Andy Warhol and asked him to produce his play, the latter believed not in a joke, but downright in a set up. Because at that time, he was not in the odor of holiness with the authorities, as he told in his memoirs, co-written with Pat Hackett and published in the 80s: “I quickly took a look at it and it was so lewd, I thought it was working for the police and it was some kind of incitement to crime”. Andy Warhol ends up telling him that he has misplaced the manuscript and, in return, offers Valérie Solanas a role in the film. I, a Man.

It was not until 1999 that the text was found. Director George Coates directs it. It was only in 2014 that it was published for the first time in the United States.

Each dialogue is finely chiseled, rhythmic, everything hits the spot. “It’s extremely built”, tells us the author Wendy Delorme, to whom we owe in particular The time of fire will come at Cambourakis and who translated this first French edition of the play.

The Story of In Your Ass

“In your ass, it’s a fierce and hilarious pamphlet that comes in the form of boulevard theater”, summarizes Wendy Delorme.

The short play features the cheeky Bongi Perez, a sort of incarnation of Valérie Solanas, who like her, prostitutes herself. As they meet and interact, it highlights and denounces the norms, the patriarchal springs and the hypocrisy of the American society of the 60s with a harsh and terribly corrosive spirit.

“She is funny, and her humor is a weapon”, explains Wendy Delorme. “The way she brings form and content together is an example to follow, it’s a source of inspiration. One of the problems in getting the facts about sexual violence across is precisely who you talk to and how you do it. Sometimes a message does not get through, because its enunciation does not get through. Valérie Solanas, while being radical, while seeming excessive, always manages to get a message across.”

Radical, extreme, rabid… There is no shortage of adjectives to qualify Valérie Solanas and her provocations. ‘In Your Ass’ do not take gloves and shows all the irreverence of this author totally out of step with the times : “She is way ahead of her time”, summarizes Wendy Delorme.

“She wrote Dans Ton Cul when we weren’t yet talking about gender issues. She was brilliant, off the charts, but that wasn’t a choice on her part. She went to college, but in her day, women were said to go to college to find a husband and were never given positions in research labs. Her rage comes from there too, she can’t live in that world. “

She is finally even too transgressive for the already very transgressive Factory, she does not fit into the codes of the studio where Andy Warhol and his clique of marginals and artists gather, in no way resembling the stars who gravitate around the artist and populate his universe.

After shooting Andy Warhol, she is brought to justice and sent to a psychiatric hospital, where she is diagnosed with schizophrenia. This assassination attempt makes her ironically famous.

The other major work of Valérie Solanas is of course SCUM Manifesto (SCUM for Society for Cutting Up Men, in other words “Society to emasculate men”), in which Valérie Solanas spits this desire to eliminate men. “Un funny and jubilant text, cathartic and humorous. It’s a big puppet that has real political power” describes the author Chloé Delaume, in an article in the World which celebrates 50 years of the work of Valérie Solanas. It was reissued in France in 2021 by Fayard with an afterword by Lauren Bastide.

In Your Ass also exists through a translation into French and a radio play produced by a collective TPG (Trans Pédés Gouines). It is broadcast on Station Station, the media of La Station — Gare des Mines.

Why you should read Dans Ton Cul, a work by Valérie Solanas as funny as it is gritty and radical. By Steven Felton. Soul Mirror One, August 7, 2022.

It is often presented for two feats of arms: the publication of SCUM Manifesto in 1967, feminist firebrand and misandre and the attempted assassination of Andy Warhol the following year. Valerie Solanas was radical feminist figure born in 1936 and died in 1988, is again highlighted through the publication in May 2022 and for the first time in France of In Your Ass. This play was translated in France by Wendy Delorme and published by Éditions Fayardin the 1001 Nights collection.

An opportunity to see that the anger of Valérie Solanas is still alive, that his verve still hits the mark, and that his denunciation of male domination and capitalism finds still resonates with feminists today.

How In Your Ass Almost Never Came to Be

In Your Ass (in English Up Your Ass), it is a work of around thirty pages, which Valérie Solanas took three years to write. Claimed lesbian, she then lives in New York, tries to become a writer and earns her living by prostituting herself.

His play almost remained lost in limbo : when in 1967, Valérie Solanas presented her manuscript to Andy Warhol and asked him to produce his play, the latter believed not in a joke, but downright in a set up. Because at that time, he was not in the odor of holiness with the authorities, as he told in his memoirs, co-written with Pat Hackett and published in the 80s: “I quickly took a look at it and it was so lewd, I thought it was working for the police and it was some kind of incitement to crime”. Andy Warhol ends up telling him that he has misplaced the manuscript and, in return, offers Valérie Solanas a role in the film. I, a Man.

It was not until 1999 that the text was found. Director George Coates directs it. It was only in 2014 that it was published for the first time in the United States.

Each dialogue is finely chiseled, rhythmic, everything hits the spot. “It’s extremely built”, tells us the author Wendy Delorme, to whom we owe in particular The time of fire will come at Cambourakis and who translated this first French edition of the play.

The Story of In Your Ass

“In your ass, it’s a fierce and hilarious pamphlet that comes in the form of boulevard theater”, summarizes Wendy Delorme.

The short play features the cheeky Bongi Perez, a sort of incarnation of Valérie Solanas, who like her, prostitutes herself. As they meet and interact, it highlights and denounces the norms, the patriarchal springs and the hypocrisy of the American society of the 60s with a harsh and terribly corrosive spirit.

“She is funny, and her humor is a weapon”, explains Wendy Delorme. “The way she brings form and content together is an example to follow, it’s a source of inspiration. One of the problems in getting the facts about sexual violence across is precisely who you talk to and how you do it. Sometimes a message does not get through, because its enunciation does not get through. Valérie Solanas, while being radical, while seeming excessive, always manages to get a message across.”

Radical, extreme, rabid… There is no shortage of adjectives to qualify Valérie Solanas and her provocations. ‘In Your Ass’ do not take gloves and shows all the irreverence of this author totally out of step with the times : “She is way ahead of her time”, summarizes Wendy Delorme.

“She wrote Dans Ton Cul when we weren’t yet talking about gender issues. She was brilliant, off the charts, but that wasn’t a choice on her part. She went to college, but in her day, women were said to go to college to find a husband and were never given positions in research labs. Her rage comes from there too, she can’t live in that world. “

She is finally even too transgressive for the already very transgressive Factory, she does not fit into the codes of the studio where Andy Warhol and his clique of marginals and artists gather, in no way resembling the stars who gravitate around the artist and populate his universe.

After shooting Andy Warhol, she is brought to justice and sent to a psychiatric hospital, where she is diagnosed with schizophrenia. This assassination attempt makes her ironically famous.

The other major work of Valérie Solanas is of course SCUM Manifesto (SCUM for Society for Cutting Up Men, in other words “Society to emasculate men”), in which Valérie Solanas spits this desire to eliminate men. “Un funny and jubilant text, cathartic and humorous. It’s a big puppet that has real political power” describes the author Chloé Delaume, in an article in the World which celebrates 50 years of the work of Valérie Solanas. It was reissued in France in 2021 by Fayard with an afterword by Lauren Bastide.

In Your Ass also exists through a translation into French and a radio play produced by a collective TPG (Trans Pédés Gouines). It is broadcast on Station Station, the media of La Station — Gare des Mines.

Why you should read Dans Ton Cul, a work by Valérie Solanas as funny as it is gritty and radical. By Steven Felton. Soul Mirror One, August 7, 2022.

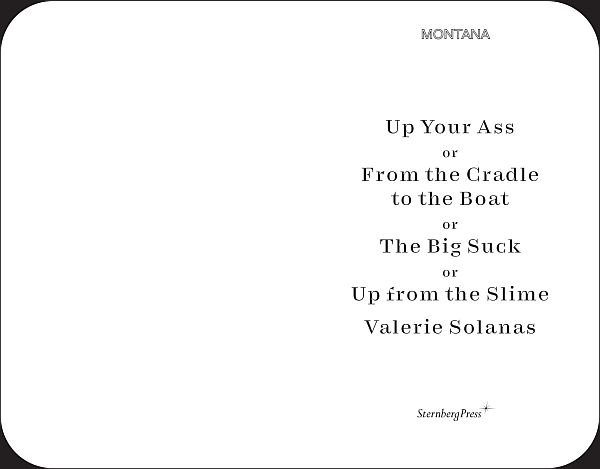

Valerie

Solanas’s rarely published, legendary play, Up Your Ass, explodes social and

sexual mores and the hypocritical, patriarchal culture that produces them

through her signature irreverence and wit, incisiveness and camp. The play,

whose full title is Up Your Ass or From the Cradle to the Boat or The Big Suck

or Up from the Slime, marches out a cast of screwy stereotypes: the unknowing

john, the frothy career girl, the boring male narcissist, two catty drag

queens, the sex-depraved housewife, and a pair of racialized pickup artists,

among others. At the center is protagonist Bongi Perez—a thinly veiled

Solanas—a sardonic, gender-bending hustler who escorts us through the back

alleys of her street life. The fictionalized predecessor to SCUM Manifesto, the

play shares the same grand, subversive, implicative language, equally spitting

and winking, embracing the margins, the scum, and selling a trick along the

way.

Sternberg Press

Sternberg Press

For a

while there, I became obsessed with Valerie Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto. How can

one not, with this opening line?

“Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation, and destroy the male sex.”

This extraordinary opening sentence starts in a mood of studied nonchalance, its participle “being” introducing as a given something which may in fact require argument. It is a sentence which starts in a distinctly camp mode, conjuring a cocktail-party wit—leaning on a bar perhaps—but which, by the time it becomes declarative, swerves to a stark, deadpan seriousness. It showcases Solanas’s intense penchant for lists, here enumerating casually asserted yet wildly ambitious demands. It displays an impeccable sense of rhythm and comedic timing, the final devastating words landing with an almost shoulder-shrugging obnoxiousness. The manifesto’s egregious unreasonableness turns on the word “only” in that perfect first sentence. I laughed out loud in a library on first reading.

I’m not sure Solanas intended the manifesto to be funny. Jeremiah Newton, a 17-year-old boy who turned up for auditions for her play, Up Your Ass, has said that “she wasn’t a comedian by any stretch. Just the fact that she was so serious made her funny.” Seriousness and impatience are key to the manifesto. In an interview in the Village Voice in 1967, Solanas answered Robert Marmorstein, who had asked if she was “serious about the SCUM thing,” by saying “Christ! Of course I’m serious. I’m dead serious.”

Pressed on why peaceful revolution wasn’t possible, she said “we’re impatient”; “I’m not going to be around 100 years from now. I want a piece of a groovy world myself. That peaceful shit is for the birds.” Vivian Gornick has rightly described Solanas’s voice as a voice “beyond reason, beyond negotiation,” but in this disarming statement of desire—I want a piece of a groovy world myself—we glimpse also the longing and perhaps the deprivation that might underlie it.

SCUM Manifesto is tremendous, an awe-inspiring, thrilling piece of writing. It has an urgency and a rage in dialogue with a ludic enjoyment in pure language, as if Solanas has been carried on a wave of her own linguistic capacity and is having a wild ride. It baldly aims to bring forth a future that she makes sound utterly reasonable. She is perennially irritated by others’ slowness, their failure to have reached the self-evident conclusions that she has. Things are very clear for her; hallucinatorily sharp and obvious. It’s uncanny to read; it’s both objectionable and lucid, lucid to the point of being a lurid fantasy.

Amongst much else, she advocates membership of the “unwork force, the fuck-up force,” elaborating arguments for automation that have since flourished in left discourse; she shruggingly asserts assisted reproduction as a self-evident inevitability; she dissects what some might now call emotional labor; she anticipates the ubiquitous surveillance that we’re now in thrall to, as well as a “perpetual hardness technique” (such as Viagra).

And all this from the gutter, from a precarious, hand-to-mouth existence on the streets of New York, in 1967, its author hawking her mimeographed pamphlet—one of the most searing, brilliant, grandiose feminist texts ever written—around town in an increasingly desperate state.

*

Daddy Issues, my short book about fathers and daughters, emerged in part from the phenomenon of #MeToo; the anguished, rageful reckoning with violence against women that swept through the media in 2017 and 2018. #MeToo elicited plentiful metaphors of beginnings and endings, of tsunamis washing shame away, of wrongdoings being exposed to the light of day and of truth, of a cleansing and a destruction all at once.

Bad men—boyfriends, sexual partners, and bosses in particular—were subjected to intense scrutiny. But fathers seemed to be largely absent from the rhetoric that swirled, and from the remarkable rise in prominence of feminism in the last ten years. Was this the familiar insulation of the private realm, the family, from scrutiny? Had feminism forgotten about fathers?

Daddy Issues also emerged from a fascination I’d long had with that phrase—”daddy issues”; a phrase routinely, knowingly, casually thrown out about a woman’s sexual choices. It is usually invoked to mock a woman for choosing a man who can be construed as a version of her father—by virtue of his age, status, or power. It nods to the power of the father and the patriarch—but then laughs at a woman for being in thrall to these. It fleetingly sees something clearly, but then turns on the woman. It serves to deflect attention and locate in the other—the woman, the girl—dynamics that are interrelational, social, and political.

The phrase also takes as a given, and then scorns, the possibility that our lives and our sexual desires are profoundly shaped by our relationships to our parents or caregivers. This terrain—infantile sexuality, Oedipal desires—often induces a phobic shudder. The phrase “daddy issues” curiously acknowledges this terrain, however, only to then reject it, turning it into a source of derision, at the cost of the women, who, as its target, are asked to be accountable for their sexual and romantic choices.

This is a familiar dynamic: the disproportionate spotlighting of women’s responsibility for sexual relations. A dynamic which, incidentally or not, is what #MeToo was trying—often clumsily, unsteadily—to address and possibly invert. Some—not all—of the disquiet about #MeToo may come from a feeling that simply inverting this structure—turning the spotlight around and interrogating male sexuality—may not be the self-evident solution that it can be felt to be.

But in Daddy Issues, I wanted to explore how representations of fathers and daughters—in fiction, in film, on TV, in public families—do a tremendous amount of work, teaching us lessons in gender and in heterosexuality, while also revealing and reinscribing an enduring horror at female sexuality—particularly a girl’s emerging sexuality. What happens when we look more closely at “daughter issues”—those of fathers and of the culture more widely?

*

Daddy Issues was a flight of fancy—a format in which I could write something short and fast, without thinking too much about it. Partly this was of necessity; it was commissioned, and by the time I found time for it, I had to squeeze the writing into busy days, writing bits here and there, and not having time to get too self-conscious about it. It came from a place of anger, sadness, unresolved difficulty, but it felt joyous to write. Could I, I wondered, derive some kind of wicked pleasure from dashing off a text that simply leaned into my own hostility, in a perhaps unreasonable, deadpan way? I don’t think Daddy Issues reads at all like SCUM Manifesto, but I know it was there, hovering, with its rage and violence, in my dark little book about dads.

Joanne Steele, a key figure in the emerging women’s movement of the 60s and 70s, has said that SCUM Manifesto “had an important message for women to hear. Nothing else was as virulent. She was the first to say you can hate your oppressor.” This is key. Solanas embraced her feelings of hate; not just a noble feeling of anger about injustice, but a feeling of pure hatred and disgust. Not just for men, either. All women “have a fink streak about them,” she notes, that stems from “a lifetime of living amongst men.” And she is caustic about “passive, rattle-headed Daddy’s Girl, ever eager for approval, for a pat on the head, for the ‘respect’ of any passing piece of garbage, is easily reduced to Mama, mindless ministrator to physical needs, soother of the weary, apey brow, booster of the tiny, appreciator of contemptible, a hot water bottle with tits.” No one escapes Solanas’s acerbic ire.

When I see women posting on Father’s Day about their dads, it’s possible that I feel some envy, but also some shame, too, about having much more mixed feelings than many of these posts convey. And yet mixed feelings—ambivalence—are the natural state of things, from the day we are born. Mothers, fathers, caregivers provide but also frustrate, and they have to, if they are to provide the conditions for their infants’ development. Aggression and hatred are an inevitable and necessary part of development for infants, and create the possibility for so much else, including love.

Donald Winnicott argued that the child needs to hate and defy someone, without there being a complete rupture in the relationship, in order to develop a sense of self. Adam Phillips has written of the requirement on parents to be both “sufficiently resilient and responsive” to be able to “withstand the full blast of the primitive love impulse”; the full blast that includes aggression. That’s what this little book felt like to me: a blast of aggression that it felt important, and pleasurable, for me to give voice to. Could I be ruthless, as Winnicott argues the baby needs to be in relation to its caregivers?

Solanas took a refusal of deference towards men to a mad, thrilling extent. Was I doing something similar, digging my heels in and refusing any concession of warmth to fathers? Could I write a book about fathers that could play with my own aggression—my need for aggression—and come out safely on the other side? I was diving in, perhaps, to my difficult feelings in the hope that really reckoning with them might be transformative. Writing Daddy Issues was, I think now, an experiment in attempting to destroy an object who could, hopefully, survive that destruction. It was an attempt, in Winnicott’s terms, to feel real.

*

The obvious problem with SCUM Manifesto is that Solanas made good on her promises. She shot Andy Warhol, who survived, but only just. How does one read a book about destroying the male sex when you know the author tried to kill a man and irreparably changed his life? Solanas had been on the periperhy of Warhol’s Factory, Solanas, and she had interested him—he cast her in I, A Man. But then he lost interest and also lost her play. They were both outsiders, Catholics from blue-collar immigrant families, but for Solanas, Warhol (along with her publisher Maurice Girodias) became a metaphor for deception, withholding, and profit—a figure of paranoia.

Yet, as Breanne Fahs argues in her book on Solanas, “Valerie exhibited a unique blend of schizophrenic paranoia and outright accuracy.” Kate Millett has said that “even people who respected Warhol and his work thought that people at the Factory were being used as cannon fodder for avant-garde art.” As Olivia Laing has written of Solanas, “just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you.” Solanas was excluded and quite possibly ill-treated, not just by the worlds she gravitated towards in New York, but in her volatile early life too. She lived an errant and erratic life that included imprisonment and hospitalization, and died aged 52, her body having been left several days before she was found.

Plenty have found SCUM Manifesto more objectionable than anything else, though plenty of writers (Andrea Long Chu, Breanne Fahs, Avitall Ronell, Olivia Laing) have, like me, been enthralled and thrilled by Solanas’s writing. It feels genuinely alarming to read her, disquieting to love this “indefensible text,” as Ronell puts it. But as Ronell goes on to say, “psychosis often catches fire from a spark in the real.”

Solanas had a lot, still has a lot, to teach us. As for Daddy Issues, any violence there was safely contained in a long essay, steadied by the forces of sentence-making. Though I might have felt alarmed writing it, I guess it worked out fine. Everybody survived.

Texts

Andrea Long Chu: “On Liking Women,” n+1 30, Winter 2018 · Olivia Laing, The Lonely City (Picador, 2016) · Breanne Fahs, Valerie Solanas: The Defiant Life of the Woman who Wrote SCUM (and Shot Andy Warhol) (Feminist Press, 2014) · Avitall Ronell, “Deviant Payback: The Aims of Valerie Solanas,” introduction to SCUM Manifesto (Verso, 2004, 2015)

Katherine Angel on Valerie Solanas, Bad Dads, and the Literary Pleasures of Pure Rage. By Katherine Angel. LitHub, July 7, 2022.

“Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation, and destroy the male sex.”

This extraordinary opening sentence starts in a mood of studied nonchalance, its participle “being” introducing as a given something which may in fact require argument. It is a sentence which starts in a distinctly camp mode, conjuring a cocktail-party wit—leaning on a bar perhaps—but which, by the time it becomes declarative, swerves to a stark, deadpan seriousness. It showcases Solanas’s intense penchant for lists, here enumerating casually asserted yet wildly ambitious demands. It displays an impeccable sense of rhythm and comedic timing, the final devastating words landing with an almost shoulder-shrugging obnoxiousness. The manifesto’s egregious unreasonableness turns on the word “only” in that perfect first sentence. I laughed out loud in a library on first reading.

I’m not sure Solanas intended the manifesto to be funny. Jeremiah Newton, a 17-year-old boy who turned up for auditions for her play, Up Your Ass, has said that “she wasn’t a comedian by any stretch. Just the fact that she was so serious made her funny.” Seriousness and impatience are key to the manifesto. In an interview in the Village Voice in 1967, Solanas answered Robert Marmorstein, who had asked if she was “serious about the SCUM thing,” by saying “Christ! Of course I’m serious. I’m dead serious.”

Pressed on why peaceful revolution wasn’t possible, she said “we’re impatient”; “I’m not going to be around 100 years from now. I want a piece of a groovy world myself. That peaceful shit is for the birds.” Vivian Gornick has rightly described Solanas’s voice as a voice “beyond reason, beyond negotiation,” but in this disarming statement of desire—I want a piece of a groovy world myself—we glimpse also the longing and perhaps the deprivation that might underlie it.

SCUM Manifesto is tremendous, an awe-inspiring, thrilling piece of writing. It has an urgency and a rage in dialogue with a ludic enjoyment in pure language, as if Solanas has been carried on a wave of her own linguistic capacity and is having a wild ride. It baldly aims to bring forth a future that she makes sound utterly reasonable. She is perennially irritated by others’ slowness, their failure to have reached the self-evident conclusions that she has. Things are very clear for her; hallucinatorily sharp and obvious. It’s uncanny to read; it’s both objectionable and lucid, lucid to the point of being a lurid fantasy.

Amongst much else, she advocates membership of the “unwork force, the fuck-up force,” elaborating arguments for automation that have since flourished in left discourse; she shruggingly asserts assisted reproduction as a self-evident inevitability; she dissects what some might now call emotional labor; she anticipates the ubiquitous surveillance that we’re now in thrall to, as well as a “perpetual hardness technique” (such as Viagra).

And all this from the gutter, from a precarious, hand-to-mouth existence on the streets of New York, in 1967, its author hawking her mimeographed pamphlet—one of the most searing, brilliant, grandiose feminist texts ever written—around town in an increasingly desperate state.

*

Daddy Issues, my short book about fathers and daughters, emerged in part from the phenomenon of #MeToo; the anguished, rageful reckoning with violence against women that swept through the media in 2017 and 2018. #MeToo elicited plentiful metaphors of beginnings and endings, of tsunamis washing shame away, of wrongdoings being exposed to the light of day and of truth, of a cleansing and a destruction all at once.

Bad men—boyfriends, sexual partners, and bosses in particular—were subjected to intense scrutiny. But fathers seemed to be largely absent from the rhetoric that swirled, and from the remarkable rise in prominence of feminism in the last ten years. Was this the familiar insulation of the private realm, the family, from scrutiny? Had feminism forgotten about fathers?

Daddy Issues also emerged from a fascination I’d long had with that phrase—”daddy issues”; a phrase routinely, knowingly, casually thrown out about a woman’s sexual choices. It is usually invoked to mock a woman for choosing a man who can be construed as a version of her father—by virtue of his age, status, or power. It nods to the power of the father and the patriarch—but then laughs at a woman for being in thrall to these. It fleetingly sees something clearly, but then turns on the woman. It serves to deflect attention and locate in the other—the woman, the girl—dynamics that are interrelational, social, and political.

The phrase also takes as a given, and then scorns, the possibility that our lives and our sexual desires are profoundly shaped by our relationships to our parents or caregivers. This terrain—infantile sexuality, Oedipal desires—often induces a phobic shudder. The phrase “daddy issues” curiously acknowledges this terrain, however, only to then reject it, turning it into a source of derision, at the cost of the women, who, as its target, are asked to be accountable for their sexual and romantic choices.

This is a familiar dynamic: the disproportionate spotlighting of women’s responsibility for sexual relations. A dynamic which, incidentally or not, is what #MeToo was trying—often clumsily, unsteadily—to address and possibly invert. Some—not all—of the disquiet about #MeToo may come from a feeling that simply inverting this structure—turning the spotlight around and interrogating male sexuality—may not be the self-evident solution that it can be felt to be.

But in Daddy Issues, I wanted to explore how representations of fathers and daughters—in fiction, in film, on TV, in public families—do a tremendous amount of work, teaching us lessons in gender and in heterosexuality, while also revealing and reinscribing an enduring horror at female sexuality—particularly a girl’s emerging sexuality. What happens when we look more closely at “daughter issues”—those of fathers and of the culture more widely?

*

Daddy Issues was a flight of fancy—a format in which I could write something short and fast, without thinking too much about it. Partly this was of necessity; it was commissioned, and by the time I found time for it, I had to squeeze the writing into busy days, writing bits here and there, and not having time to get too self-conscious about it. It came from a place of anger, sadness, unresolved difficulty, but it felt joyous to write. Could I, I wondered, derive some kind of wicked pleasure from dashing off a text that simply leaned into my own hostility, in a perhaps unreasonable, deadpan way? I don’t think Daddy Issues reads at all like SCUM Manifesto, but I know it was there, hovering, with its rage and violence, in my dark little book about dads.

Joanne Steele, a key figure in the emerging women’s movement of the 60s and 70s, has said that SCUM Manifesto “had an important message for women to hear. Nothing else was as virulent. She was the first to say you can hate your oppressor.” This is key. Solanas embraced her feelings of hate; not just a noble feeling of anger about injustice, but a feeling of pure hatred and disgust. Not just for men, either. All women “have a fink streak about them,” she notes, that stems from “a lifetime of living amongst men.” And she is caustic about “passive, rattle-headed Daddy’s Girl, ever eager for approval, for a pat on the head, for the ‘respect’ of any passing piece of garbage, is easily reduced to Mama, mindless ministrator to physical needs, soother of the weary, apey brow, booster of the tiny, appreciator of contemptible, a hot water bottle with tits.” No one escapes Solanas’s acerbic ire.

When I see women posting on Father’s Day about their dads, it’s possible that I feel some envy, but also some shame, too, about having much more mixed feelings than many of these posts convey. And yet mixed feelings—ambivalence—are the natural state of things, from the day we are born. Mothers, fathers, caregivers provide but also frustrate, and they have to, if they are to provide the conditions for their infants’ development. Aggression and hatred are an inevitable and necessary part of development for infants, and create the possibility for so much else, including love.

Donald Winnicott argued that the child needs to hate and defy someone, without there being a complete rupture in the relationship, in order to develop a sense of self. Adam Phillips has written of the requirement on parents to be both “sufficiently resilient and responsive” to be able to “withstand the full blast of the primitive love impulse”; the full blast that includes aggression. That’s what this little book felt like to me: a blast of aggression that it felt important, and pleasurable, for me to give voice to. Could I be ruthless, as Winnicott argues the baby needs to be in relation to its caregivers?

Solanas took a refusal of deference towards men to a mad, thrilling extent. Was I doing something similar, digging my heels in and refusing any concession of warmth to fathers? Could I write a book about fathers that could play with my own aggression—my need for aggression—and come out safely on the other side? I was diving in, perhaps, to my difficult feelings in the hope that really reckoning with them might be transformative. Writing Daddy Issues was, I think now, an experiment in attempting to destroy an object who could, hopefully, survive that destruction. It was an attempt, in Winnicott’s terms, to feel real.

*

The obvious problem with SCUM Manifesto is that Solanas made good on her promises. She shot Andy Warhol, who survived, but only just. How does one read a book about destroying the male sex when you know the author tried to kill a man and irreparably changed his life? Solanas had been on the periperhy of Warhol’s Factory, Solanas, and she had interested him—he cast her in I, A Man. But then he lost interest and also lost her play. They were both outsiders, Catholics from blue-collar immigrant families, but for Solanas, Warhol (along with her publisher Maurice Girodias) became a metaphor for deception, withholding, and profit—a figure of paranoia.

Yet, as Breanne Fahs argues in her book on Solanas, “Valerie exhibited a unique blend of schizophrenic paranoia and outright accuracy.” Kate Millett has said that “even people who respected Warhol and his work thought that people at the Factory were being used as cannon fodder for avant-garde art.” As Olivia Laing has written of Solanas, “just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you.” Solanas was excluded and quite possibly ill-treated, not just by the worlds she gravitated towards in New York, but in her volatile early life too. She lived an errant and erratic life that included imprisonment and hospitalization, and died aged 52, her body having been left several days before she was found.

Plenty have found SCUM Manifesto more objectionable than anything else, though plenty of writers (Andrea Long Chu, Breanne Fahs, Avitall Ronell, Olivia Laing) have, like me, been enthralled and thrilled by Solanas’s writing. It feels genuinely alarming to read her, disquieting to love this “indefensible text,” as Ronell puts it. But as Ronell goes on to say, “psychosis often catches fire from a spark in the real.”

Solanas had a lot, still has a lot, to teach us. As for Daddy Issues, any violence there was safely contained in a long essay, steadied by the forces of sentence-making. Though I might have felt alarmed writing it, I guess it worked out fine. Everybody survived.

Texts

Andrea Long Chu: “On Liking Women,” n+1 30, Winter 2018 · Olivia Laing, The Lonely City (Picador, 2016) · Breanne Fahs, Valerie Solanas: The Defiant Life of the Woman who Wrote SCUM (and Shot Andy Warhol) (Feminist Press, 2014) · Avitall Ronell, “Deviant Payback: The Aims of Valerie Solanas,” introduction to SCUM Manifesto (Verso, 2004, 2015)

Katherine Angel on Valerie Solanas, Bad Dads, and the Literary Pleasures of Pure Rage. By Katherine Angel. LitHub, July 7, 2022.

Breanne

Fahs: Aileen Wuornos and Valerie Solanas are both known by many people as

perpetrators of homicidal violence against men who wronged them. Looking closely at their stories, as you do

in your new book, Requiem for a Serial Killer, and as I did in my biography of

Solanas, Valerie Solanas: The Defiant Life of the Woman Who Wrote SCUM (and

Shot Andy Warhol), their violent rage reflected the profoundly oppressive

conditions in which they lived. We can read Wuornos and Solanas as feminist

characters or as aberrations of feminism. Why should they be embraced?

Alternatively, are there aspects of them we should reject?

Phyllis Chesler: They are both feminist icons, armed Amazon figures, and, at the same time, lone, non-political actors, badasses, folk heroes, like Billy the Kid or Jesse James. They work with no one, trust no one, are literal, concrete, specific; as Solanas might say, they act, while feminists are too often women who just talk. They are also mad women, in both senses of that word. However, Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto is brilliant and daring, as well as crackpot — political theatre at its best. Wuornos does not think or write in feminist terms. Although both women have lived at the edge of the ledge, endured enormous sexual violence, and gave up babies for adoption when they were teenagers, Solanas did not become a serial killer; Wuornos did. Both women refused to be rescued by feminist leaders who came to their aid. They gave us all a right royal run for our money. I found that I was the revolutionary idealist who wanted to overthrow patriarchy and Wuornos was a petit-bourgeois capitalist, who only wanted a piece of the pie. She did not enjoy the luxury of a life of ideas.

BF: Tell me more about that — the tension between the life of ideas and the act of violence. Solanas’s writing straddled the edge of satire and seriousness, and until she shot Andy Warhol in June 1968, most considered her a “crazy” polemicist, using the SCUM Manifesto as (what she called) a “literary device” rather than as something serious. Yet, her publisher later admitted that if she hadn’t shot Warhol, he never would have published SCUM Manifesto. This suggests that women like Solanas and Wuornos need to “scream to be heard,” that there is no place for them to express rage in moderated, polite, or mediated ways. At the same time, I think we’d both agree that homicidal rage leaves a wake of destruction, particularly for women struggling with severe mental illness. Neither could really get the help they needed after committing this violence. Where does that leave those of us wanting to express rage, or (like Solanas) express radical ideas, while also wanting to embrace non-violence?

PC: I am not sure that Wuornos wanted to be “heard.” All her life she was secretive — even more so after her arrest. But once she was in jail, she became very invested in her own fame, notoriety. She was proud that she’d “made history,” zealously tried to collect all her clippings, and agonized over others being able to make money “offa” what she alone did. This behaviour is also typical for male serial killers. I do not believe that the anger you and I may feel about genocide or femicide, or what we do about it (name it, analyze it, teach it, pass legislation against it, reach out to its victims, march, even go to jail) has anything in common with individual acts of final-straw homicide. We are lucky. We are privileged — we can “de-construct” such concrete acts and try to connect with the actors. Clearly, in both Solanas’s and Wuornos’s case, they viewed the feminist do-gooders with suspicion, contempt, and perhaps hatred.

BF: It is a luxury to be able to think and write about these characters rather than live through their specific material conditions. You’ve just written a book about the much-misunderstood character of Aileen Wuornos. It is an astonishing portrait of Wuornos, filled with a sympathetic understanding of her righteous anger, her severe mental illness, and her drive toward violence. Can you talk about what drew you to her and why she matters, particularly in this moment of COVID-19, the Donald Trump presidency, #MeToo, and the intensification of women’s righteous rage?

PC: I began this book 30 years ago, set it aside, published some law review and op-ed articles about her case, forgot about the book, and then picked it up, liked the five chapters that I’d written, reconstituted my entire Wuornos archive, read everything, and then steadily worked on the book from the summer of 2019 through the summer of 2020. I was originally drawn to Wuornos’s case in 1991 and felt compelled to organize a pro bono team of experts (she wanted this) to educate her first jury about the kind of violence that so many prostituted girls and women routinely face. Her claim that she killed in self-defence was entirely believable to me, but not to anyone who has not studied prostitution, interviewed prostitutes, and who is not familiar with cases of women who have killed in self-defence and with how their cases are handled. These are burning issues that remain with us today. They are as timely now as they were in the 19th and 20th centuries. I agree with you: Wuornos may be of greater interest now than she was in her day. Women are righteously “riled up” about racial and class injustice, sexual harassment, and rape. Also, we are now watching so many movies about female assassins, women dealing with domestic violence who fight back and who kill, female detectives who carry and use guns, female counter-terrorist special agents, etc.

BF: I agree that images and stories of women fighting back are in ascendancy, and I also feel haunted by how many images and stories we have of women being victimized and terrorized. I can’t help but think that this impacts women’s consciousness. You and I are both feminist psychologists and have worked with many women in bad romantic, sexual, financial, workplace, and mental health situations, including many women who have been abused, beaten, dismissed, trivialized, and discarded by (more) powerful men. How does this work — grounded in the material conditions in which women often live — inform how you see Wuornos and Solanas? What do Wuornos and Solanas teach us about how women survive violence enacted by men?

PC: Most severely battered women and child sex abuse/rape victims rarely fully recover. They tend to repeat their original traumas, which have rendered them more, not less, vulnerable to life-long abuse. Solanas and Wuornos got guns, got even, punched up, so to speak. Wuornos took down johns who towered over her in height and outweighed her. Some had been cops and Wuornos viewed such authority as corrupt and hypocritical, just as Solanas viewed Andy Warhol and her publisher Maurice Girodias as rip-off artists who bought and owned her work for a song and planned to hold it hostage for their amusement and profit.

BF: Do you consider their acts of violence a rational — or even predictable — response to the conditions they lived in?

PC: These acts are “rational” given the abuse they suffered for so long. However, these acts are also unpredictable. Most abused women do not kill men. Their abuse has made it difficult, perhaps impossible, for them to get out of harm’s way or to defend themselves from continued harm. To kill, even in self-defence, is rare. Many battered wives have been given life sentences for finally taking the law in their own hands and killing their batterers who had vowed to kill them. Absolutely no one else stopped these batterers.

BF: In that sense, Wuornos and Solanas were aberrations. Both Wuornos and Solanas had complicated relationships with men. Solanas lived with several different male partners, was sexually abused by men, worked as a sex worker with men, publicly derided men, shot two men, and wrote a manifesto calling for the elimination of all men (SCUM Manifesto) — a manuscript written for, in her words, “whores, dykes, criminals, and homicidal maniacs.” Wuornos was sexually abused by both her brother and grandfather, worked as a sex worker with men, and shot seven johns after they raped (or attempted to rape) her. Both women expressed rage at men in extreme and violent ways. That said, they both had many complicated and arguably justified reasons for feeling the rage they felt. How are these representations of men, as imagined by Wuornos and Solanas, a reflection of normal versus extreme toxic masculinity? Additionally, because both of them relied on men as a means of financial survival, does that relationship of economic dependence predict rage, anger, and violence toward men? How do we draw lines between childhood abuse and later acts of rage and violence?

PC: The economic dependence on men alone should drive women to violence. It does not. Because, as you say, it’s “complicated.” We are (falsely) reared to see men as our protectors; Daddy will take care of us if we take care of Daddy. By and large, for many women, this “peculiar arrangement” (which is how slavery was described) works, or is acceptable. They see no other alternative. As I reveal in Requiem for a Female Serial Killer, Wuornos insisted that she did not hate men; in fact, she viewed many of her johns as “boyfriends,” and was atypically very affectionate with them. She had a series of non-john boyfriends with whom she physically fought. She did not think of herself as a “lesbian” although the only person she was able to live with for 4 1/2 years was a very butch gay woman, one whom she said she “loved.” Tyria, who took the stand against her, also said that Wuornos was not really a “lesbian.” As you’ve shown in your excellent biography of Solanas, she, too, had boyfriends — and, at the same time, in blazing prose, told us that we had to eliminate the male sex. If you read enough about who the real serial killers are (men) and if you understand the nature of battering, and prostitution (mainly driven by men for money and “pleasure,”) it is not hard to understand Solanas’s point.

BF: Both Wuornos and Solanas are figures of anger but also of tragedy, resilience, and victimization. You’ve written extensively about how, when anger turns inward toward the self, it appears as depression. Both Wuornos and Solanas managed to resist a deeply depressive way of relating to their conditions of abuse and degradation. Why is it so hard for many women to validate and nurture their own anger? What lessons should we learn from Wuornos and Solanas?

PC: Women who act as if they are men — who act out their anger — were once diagnosed as “crazy” and punished as criminals. They have not been forgiven as many men are. I am not sure that anger turned outward is a way of expressing or avoiding depression. It might not even be “anger.” Women who kill their rapists or batterers in self-defence are often given life sentences. Wuornos killed in self-defence, at least the first time. Women do or should have the right to kill in self-defence, regardless of whether they are working as prostitutes, perhaps especially if they are, because many are battered and raped by multitudes of men, not just by one man. Most women are not permitted to express anger and then to let it go. It would be better if we learn how to do so.

BF: What would you say, drawing on the experiences of Solanas and Wuornos, to those who claim that people can engage in sex work in a consensual manner? How do their stories complicate the notions of consent, sex work, and mental health?

PC: Perhaps one to two per cent of prostituted girls and women, working alone, without pimps or Madams, especially as dominatrixes, may view what is a forced (economic) choice as a free choice. Everyone else has been trafficked into hell, especially young women of colour. As I write in Requiem:

“As an abolitionist, I do not view prostituted women with distaste or disgust — but I do see them as human sacrifices. I understand all the forces that track 98 per cent of girls and women into the ‘working life’: Dangerously dysfunctional families; physical and sexual abuse; drug addicted, absent, or imprisoned parents; serious poverty; homelessness; being racially marginalized; tricked or kidnapped into prostitution by a trafficker; sold by one’s parents; having too little education and few marketable skills; and, having absolutely no other way to eat or to feed your children.”

However, I do not view prostitution as an act of feminist resistance any more than I view marriage as one. The proposed solutions (legalization, decriminalization, etc.) will not abolish sexism, racism, poverty, war, genocide, or rape. What will? Until we find that magic bullet, starving and homeless girls and women will do whatever they can in order to afford their anesthetizing drugs so they can endure their work and put food on the table. And, as Wuornos said, men will keep taking their penises out of their pants and their money out of their pockets.

BF: Perhaps what you’re saying most clearly here is that options are limited for how oppressed people regain power, dignity, and autonomy, and that sex work cannot serve as a panacea for taking back power and dignity. One thing that sets these two women apart is their relationship to violence, and their use of violence as a way to regain dignity and power. Aileen Wuornos and Valerie Solanas exist on the margins of feminist consciousness as women who embraced violence as a form of fighting back against patriarchal oppression. Frantz Fanon wrote, in Wretched of the Earth, of the necessity of violence for oppressed people:

“From birth it is clear to him that this narrow world, strewn with prohibitions, can only be called in question by absolute violence… And it is clear that in the colonial countries the peasants alone are revolutionary, for they have nothing to lose and everything to gain. The starving peasant, outside the class system is the first among the exploited to discover that only violence pays. For him there is no compromise, no possible coming to terms; colonization and decolonization is simply a question of relative strength.”

I wonder if we can also read Wuornos and Solanas in this way, as the question of violence as useful must be seen through the lens of both class and gender simultaneously. Do people engage in violence if they have other options? Is there a place for violence in feminism? How can we make sense of women’s violence toward men outside of the framework of crimes of passion?

PC: I used to teach Fanon and Freire — Memmi too — in Women’s Studies but I’m not sure I’d do so today. Women’s position is a caste position, one that class, race, geography, education, luck, etc. does not seem to change. A girl or a woman cannot say: “No FGM for me, I believe that I’m really a boy;” “No sexual harassment my way, I’m an important scientist who is about to solve the three-body problem;” “You can’t rape me, my father is a wealthy and important man;” etc. Class and anti-colonial/anti-racism struggles have required a violent overthrow of kings and masters but have focused far less on incest, rape, woman-battering, trafficking, FGM, honour killing, femicide, etc. Legislation against sex slavery hasn’t done so, nor have conferences, brilliant books, or individual acts of sacrifice and heroism. Even vibrant feminist movements, which have named and analyzed violence against women, have failed to do so. What will? Solanas’s shot landed her in a psychiatric facility. Wuornos’s shot landed her on death row and in an execution chamber. True, if there were millions of women out there, targeting known and specific pimps, sexual harassers, pedophiles, and rapists, that would eliminate those particular fiends. But would that eliminate such practices among others and among future generations? And do we really favour vigilantism? Or mob rule?

BF: I know our job is not to provide answers to the provocative questions you raise, because in part your work is so valuable because it highlights the way that we are trapped within these systems and there is no easy solution. We are not creating a feminist utopia here, but rather, trying to better understand the nature of the trappings we are in. What do you want readers of your book, and those interested in Wuornos and Solanas more broadly, to understand about the particular conditions women are living in today?

PC: Radical feminism has been neutralized and disappeared both in the academy and in the media. Had our early 1970s work (both academic and activist) on sexual harassment and rape been continuously taught and updated, we might have had a #MeToo movement much sooner.

BF: That’s why we need radical critiques of sexism and misogyny, a “going to the roots” approach to why oppression exists in the first place. When we work in solidarity with each other on radical critiques of the status quo, new worlds open up.

Phyllis Chesler is an Emerita Professor of Psychology and Women’s Studies at the College of Staten Island (CUNY) and the author of twenty books, including Women and Madness, Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman, and A Politically Incorrect Feminist. In 1969, she co-founded the Association for Women in Psychology, and in 1974, she co-founded the National Women’s Health Network. She continues to work on political activism and legal work on behalf of women seeking political asylum.

Breanne Fahs is Professor of Women and Gender Studies at Arizona State University. She is the author of Performing Sex, Valerie Solanas, Out for Blood, Women, Sex, and Madness, and Firebrand Feminism, and co-editor of The Moral Panics of Sexuality, Transforming Contagion, and the newly released Burn It Down! Feminist Manifestos for the Revolution. She is the founder and director of the Feminist Research on Gender and Sexuality Group and also works as a clinical psychologist in private practice.

Phyllis Chesler: They are both feminist icons, armed Amazon figures, and, at the same time, lone, non-political actors, badasses, folk heroes, like Billy the Kid or Jesse James. They work with no one, trust no one, are literal, concrete, specific; as Solanas might say, they act, while feminists are too often women who just talk. They are also mad women, in both senses of that word. However, Solanas’s SCUM Manifesto is brilliant and daring, as well as crackpot — political theatre at its best. Wuornos does not think or write in feminist terms. Although both women have lived at the edge of the ledge, endured enormous sexual violence, and gave up babies for adoption when they were teenagers, Solanas did not become a serial killer; Wuornos did. Both women refused to be rescued by feminist leaders who came to their aid. They gave us all a right royal run for our money. I found that I was the revolutionary idealist who wanted to overthrow patriarchy and Wuornos was a petit-bourgeois capitalist, who only wanted a piece of the pie. She did not enjoy the luxury of a life of ideas.

BF: Tell me more about that — the tension between the life of ideas and the act of violence. Solanas’s writing straddled the edge of satire and seriousness, and until she shot Andy Warhol in June 1968, most considered her a “crazy” polemicist, using the SCUM Manifesto as (what she called) a “literary device” rather than as something serious. Yet, her publisher later admitted that if she hadn’t shot Warhol, he never would have published SCUM Manifesto. This suggests that women like Solanas and Wuornos need to “scream to be heard,” that there is no place for them to express rage in moderated, polite, or mediated ways. At the same time, I think we’d both agree that homicidal rage leaves a wake of destruction, particularly for women struggling with severe mental illness. Neither could really get the help they needed after committing this violence. Where does that leave those of us wanting to express rage, or (like Solanas) express radical ideas, while also wanting to embrace non-violence?

PC: I am not sure that Wuornos wanted to be “heard.” All her life she was secretive — even more so after her arrest. But once she was in jail, she became very invested in her own fame, notoriety. She was proud that she’d “made history,” zealously tried to collect all her clippings, and agonized over others being able to make money “offa” what she alone did. This behaviour is also typical for male serial killers. I do not believe that the anger you and I may feel about genocide or femicide, or what we do about it (name it, analyze it, teach it, pass legislation against it, reach out to its victims, march, even go to jail) has anything in common with individual acts of final-straw homicide. We are lucky. We are privileged — we can “de-construct” such concrete acts and try to connect with the actors. Clearly, in both Solanas’s and Wuornos’s case, they viewed the feminist do-gooders with suspicion, contempt, and perhaps hatred.

BF: It is a luxury to be able to think and write about these characters rather than live through their specific material conditions. You’ve just written a book about the much-misunderstood character of Aileen Wuornos. It is an astonishing portrait of Wuornos, filled with a sympathetic understanding of her righteous anger, her severe mental illness, and her drive toward violence. Can you talk about what drew you to her and why she matters, particularly in this moment of COVID-19, the Donald Trump presidency, #MeToo, and the intensification of women’s righteous rage?

PC: I began this book 30 years ago, set it aside, published some law review and op-ed articles about her case, forgot about the book, and then picked it up, liked the five chapters that I’d written, reconstituted my entire Wuornos archive, read everything, and then steadily worked on the book from the summer of 2019 through the summer of 2020. I was originally drawn to Wuornos’s case in 1991 and felt compelled to organize a pro bono team of experts (she wanted this) to educate her first jury about the kind of violence that so many prostituted girls and women routinely face. Her claim that she killed in self-defence was entirely believable to me, but not to anyone who has not studied prostitution, interviewed prostitutes, and who is not familiar with cases of women who have killed in self-defence and with how their cases are handled. These are burning issues that remain with us today. They are as timely now as they were in the 19th and 20th centuries. I agree with you: Wuornos may be of greater interest now than she was in her day. Women are righteously “riled up” about racial and class injustice, sexual harassment, and rape. Also, we are now watching so many movies about female assassins, women dealing with domestic violence who fight back and who kill, female detectives who carry and use guns, female counter-terrorist special agents, etc.

BF: I agree that images and stories of women fighting back are in ascendancy, and I also feel haunted by how many images and stories we have of women being victimized and terrorized. I can’t help but think that this impacts women’s consciousness. You and I are both feminist psychologists and have worked with many women in bad romantic, sexual, financial, workplace, and mental health situations, including many women who have been abused, beaten, dismissed, trivialized, and discarded by (more) powerful men. How does this work — grounded in the material conditions in which women often live — inform how you see Wuornos and Solanas? What do Wuornos and Solanas teach us about how women survive violence enacted by men?

PC: Most severely battered women and child sex abuse/rape victims rarely fully recover. They tend to repeat their original traumas, which have rendered them more, not less, vulnerable to life-long abuse. Solanas and Wuornos got guns, got even, punched up, so to speak. Wuornos took down johns who towered over her in height and outweighed her. Some had been cops and Wuornos viewed such authority as corrupt and hypocritical, just as Solanas viewed Andy Warhol and her publisher Maurice Girodias as rip-off artists who bought and owned her work for a song and planned to hold it hostage for their amusement and profit.

BF: Do you consider their acts of violence a rational — or even predictable — response to the conditions they lived in?

PC: These acts are “rational” given the abuse they suffered for so long. However, these acts are also unpredictable. Most abused women do not kill men. Their abuse has made it difficult, perhaps impossible, for them to get out of harm’s way or to defend themselves from continued harm. To kill, even in self-defence, is rare. Many battered wives have been given life sentences for finally taking the law in their own hands and killing their batterers who had vowed to kill them. Absolutely no one else stopped these batterers.

BF: In that sense, Wuornos and Solanas were aberrations. Both Wuornos and Solanas had complicated relationships with men. Solanas lived with several different male partners, was sexually abused by men, worked as a sex worker with men, publicly derided men, shot two men, and wrote a manifesto calling for the elimination of all men (SCUM Manifesto) — a manuscript written for, in her words, “whores, dykes, criminals, and homicidal maniacs.” Wuornos was sexually abused by both her brother and grandfather, worked as a sex worker with men, and shot seven johns after they raped (or attempted to rape) her. Both women expressed rage at men in extreme and violent ways. That said, they both had many complicated and arguably justified reasons for feeling the rage they felt. How are these representations of men, as imagined by Wuornos and Solanas, a reflection of normal versus extreme toxic masculinity? Additionally, because both of them relied on men as a means of financial survival, does that relationship of economic dependence predict rage, anger, and violence toward men? How do we draw lines between childhood abuse and later acts of rage and violence?

PC: The economic dependence on men alone should drive women to violence. It does not. Because, as you say, it’s “complicated.” We are (falsely) reared to see men as our protectors; Daddy will take care of us if we take care of Daddy. By and large, for many women, this “peculiar arrangement” (which is how slavery was described) works, or is acceptable. They see no other alternative. As I reveal in Requiem for a Female Serial Killer, Wuornos insisted that she did not hate men; in fact, she viewed many of her johns as “boyfriends,” and was atypically very affectionate with them. She had a series of non-john boyfriends with whom she physically fought. She did not think of herself as a “lesbian” although the only person she was able to live with for 4 1/2 years was a very butch gay woman, one whom she said she “loved.” Tyria, who took the stand against her, also said that Wuornos was not really a “lesbian.” As you’ve shown in your excellent biography of Solanas, she, too, had boyfriends — and, at the same time, in blazing prose, told us that we had to eliminate the male sex. If you read enough about who the real serial killers are (men) and if you understand the nature of battering, and prostitution (mainly driven by men for money and “pleasure,”) it is not hard to understand Solanas’s point.

BF: Both Wuornos and Solanas are figures of anger but also of tragedy, resilience, and victimization. You’ve written extensively about how, when anger turns inward toward the self, it appears as depression. Both Wuornos and Solanas managed to resist a deeply depressive way of relating to their conditions of abuse and degradation. Why is it so hard for many women to validate and nurture their own anger? What lessons should we learn from Wuornos and Solanas?

PC: Women who act as if they are men — who act out their anger — were once diagnosed as “crazy” and punished as criminals. They have not been forgiven as many men are. I am not sure that anger turned outward is a way of expressing or avoiding depression. It might not even be “anger.” Women who kill their rapists or batterers in self-defence are often given life sentences. Wuornos killed in self-defence, at least the first time. Women do or should have the right to kill in self-defence, regardless of whether they are working as prostitutes, perhaps especially if they are, because many are battered and raped by multitudes of men, not just by one man. Most women are not permitted to express anger and then to let it go. It would be better if we learn how to do so.

BF: What would you say, drawing on the experiences of Solanas and Wuornos, to those who claim that people can engage in sex work in a consensual manner? How do their stories complicate the notions of consent, sex work, and mental health?

PC: Perhaps one to two per cent of prostituted girls and women, working alone, without pimps or Madams, especially as dominatrixes, may view what is a forced (economic) choice as a free choice. Everyone else has been trafficked into hell, especially young women of colour. As I write in Requiem:

“As an abolitionist, I do not view prostituted women with distaste or disgust — but I do see them as human sacrifices. I understand all the forces that track 98 per cent of girls and women into the ‘working life’: Dangerously dysfunctional families; physical and sexual abuse; drug addicted, absent, or imprisoned parents; serious poverty; homelessness; being racially marginalized; tricked or kidnapped into prostitution by a trafficker; sold by one’s parents; having too little education and few marketable skills; and, having absolutely no other way to eat or to feed your children.”

However, I do not view prostitution as an act of feminist resistance any more than I view marriage as one. The proposed solutions (legalization, decriminalization, etc.) will not abolish sexism, racism, poverty, war, genocide, or rape. What will? Until we find that magic bullet, starving and homeless girls and women will do whatever they can in order to afford their anesthetizing drugs so they can endure their work and put food on the table. And, as Wuornos said, men will keep taking their penises out of their pants and their money out of their pockets.

BF: Perhaps what you’re saying most clearly here is that options are limited for how oppressed people regain power, dignity, and autonomy, and that sex work cannot serve as a panacea for taking back power and dignity. One thing that sets these two women apart is their relationship to violence, and their use of violence as a way to regain dignity and power. Aileen Wuornos and Valerie Solanas exist on the margins of feminist consciousness as women who embraced violence as a form of fighting back against patriarchal oppression. Frantz Fanon wrote, in Wretched of the Earth, of the necessity of violence for oppressed people:

“From birth it is clear to him that this narrow world, strewn with prohibitions, can only be called in question by absolute violence… And it is clear that in the colonial countries the peasants alone are revolutionary, for they have nothing to lose and everything to gain. The starving peasant, outside the class system is the first among the exploited to discover that only violence pays. For him there is no compromise, no possible coming to terms; colonization and decolonization is simply a question of relative strength.”

I wonder if we can also read Wuornos and Solanas in this way, as the question of violence as useful must be seen through the lens of both class and gender simultaneously. Do people engage in violence if they have other options? Is there a place for violence in feminism? How can we make sense of women’s violence toward men outside of the framework of crimes of passion?

PC: I used to teach Fanon and Freire — Memmi too — in Women’s Studies but I’m not sure I’d do so today. Women’s position is a caste position, one that class, race, geography, education, luck, etc. does not seem to change. A girl or a woman cannot say: “No FGM for me, I believe that I’m really a boy;” “No sexual harassment my way, I’m an important scientist who is about to solve the three-body problem;” “You can’t rape me, my father is a wealthy and important man;” etc. Class and anti-colonial/anti-racism struggles have required a violent overthrow of kings and masters but have focused far less on incest, rape, woman-battering, trafficking, FGM, honour killing, femicide, etc. Legislation against sex slavery hasn’t done so, nor have conferences, brilliant books, or individual acts of sacrifice and heroism. Even vibrant feminist movements, which have named and analyzed violence against women, have failed to do so. What will? Solanas’s shot landed her in a psychiatric facility. Wuornos’s shot landed her on death row and in an execution chamber. True, if there were millions of women out there, targeting known and specific pimps, sexual harassers, pedophiles, and rapists, that would eliminate those particular fiends. But would that eliminate such practices among others and among future generations? And do we really favour vigilantism? Or mob rule?

BF: I know our job is not to provide answers to the provocative questions you raise, because in part your work is so valuable because it highlights the way that we are trapped within these systems and there is no easy solution. We are not creating a feminist utopia here, but rather, trying to better understand the nature of the trappings we are in. What do you want readers of your book, and those interested in Wuornos and Solanas more broadly, to understand about the particular conditions women are living in today?