With its otherworldly woodcuts and ornate descriptions of imagined architecture, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili brims with an obsessive and erotic fixation on form. Demetra Vogiatzaki accompanies the hero as he wanders the pages of this quattrocento marvel, at once a story of lost love and a fever dream of antiquity.

On the right, The Worship of Priapus, featuring nineteen women and five men. In the foreground, priestesses sacrifice an ass beneath the phallic god’s herma —

A

fountain of the “little Priapus”, featuring a weight-sensitive step that, when

depressed, “raises the child’s instrument”, spraying Poliphilo’s face with cold

water

For all that we know, the original “dreamer” remains unidentified. Written in an idiosyncratic hybrid language fusing Italian, Latin, and Greek, and replete with inauthentic Egyptian hieroglyphs and an abundance of architectural and botanical jargon, the rambling text of Hypnerotomachia does little to dispel the mystery of its authorship, even though it does mirror with remarkable accuracy the composite, winding nature of its contents. An acrostic formed by the first letter of each chapter, reading “Poliam Frater Franciscus Columna Peramavit" (Brother Francesco Colonna greatly loved Polia) led scholars to identify a Dominican monk from Treviso as the author of the book. Nevertheless, the polymathy of Poliphilo — along with the cryptic and playful nature of the work as a whole — has raised doubts regarding the plausibility of this hypothesis, with some critics suggesting that “Colonna” could be a pseudonym.

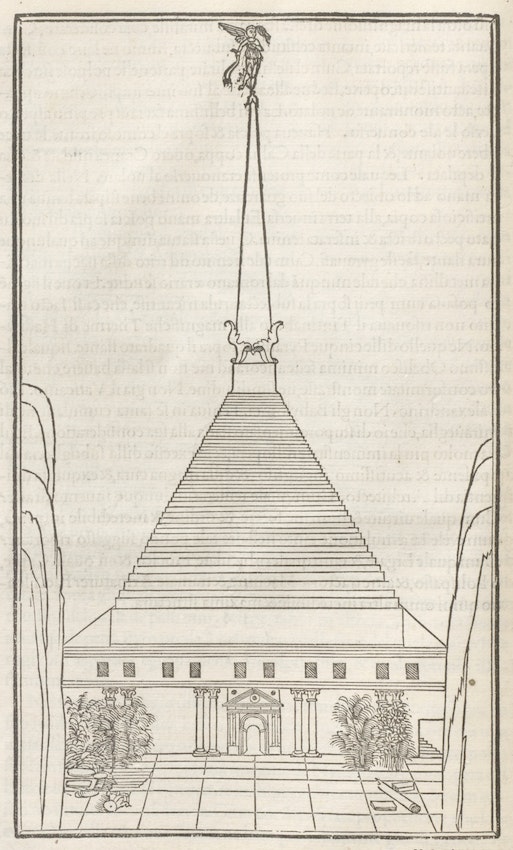

The Temple of the Sun, constructed of white Parian marble, with 1410 steps and a cornucopia-clutching winged figure

“Considered vertically, the building is an unlikely compilation of elements. On top of the temple is a plinth, and on top of the plinth is a pyramid, and on top of the pyramid is a monolithic stone cube and on top of the monolithic stone cube is an obelisk and on top of the obelisk is a bronze statue of a nymph holding an inverted cornucopia. Poised on one leg with the other elevated in arabesque, she pirouettes on a pivot with every shift of the wind, emitting a deafening shriek with every turn. “”

Left: an ornate vessel decorated with “marvelous artificial foliage, such as is not made in our times” and surmounted by a cubit-high coral tree, which is nested in a hillock “studded with incomparable gems”. Right: a perpetual fountain with harpies, scintillating emerald leaves, and a golden pomegranate tree with coral flowers containing “calyxes full of golden bees”

Poliphilo surrounded by remains of classical antiquity. A ferocious wolf eyes him with its jaws agape

Section and ground-plan of the Temple of Venus Physizoa, whose spire is capped by a bronze crescent moon and an eagle with its wings akimbo

In the centuries that followed its enigmatic appearance, Hypnerotomachia came to represent a type of architectural and artistic invention that derives its sensuous, eccentric qualities from the cryptic world of dreams, rather than from the orderly forms usually associated with Renaissance aesthetics. Yet, besides its multiple references to and deviations from architectural rules, the world in which Hypnerotomachia unfolds presents astounding continuities with the broader religious, civic, and cultural context of Venice at the time. The ruination of the world in which Poliphilo wanders coexists with the marvelous monuments he encounters in a way that is reminiscent of the double function of Christian icons in this period. For Hans Belting, the icon’s intentional fragmentation of pictorial space pointed to a transcendental world that remained intact. Accordingly, the kind of memory that these artworks heralded had “both a retrospective and, curious as it sounds, a prospective character”. The icon was not only a trace of something from the past but also something that was promised in the future. A similar dynamic is at play in Hypnerotomachia, against the backdrop of the Venetian art scene and the work of Vittore Carpaccio in particular.

From left to right: a

weathercock, with genius blowing the trumpet; a box tree pruned into the shape

of a man, whose feet rest on vases, and arms support an ornament of towers and

arch; another box tree, this one pruned in the shape of a centrepiece; and the

decorative crowning of the Temple of the Sun

Under

the guise of the dream, Hypnerotomachia seems to present a new symbolic

universe in which the complicated relationship between ancient and modern space

could be redefined. In his influential book, Unearthing the Past, Leonard

Barkan showed how the pace at which antiquities were being unearthed in the

late Quattrocento brought forth a sea change in historical, political, and

aesthetic thought. These resurfaced objects didn’t just challenge established

views on the past. They also generated new kinds of artistic expression and

appreciation, including the production and circulation of drawings and

ekphrastic narratives, the first private collections of antique fragments, and

new forms of theory and practice that embraced architecture’s inventive as well

as restorative potential.

Yet

Hypnerotomachia is much more than an architectural manifesto. These intricate

negotiations also seem to emerge through the orchestration of Poliphilo’s and

Polia’s triste. Almost halfway through his dream, Poliphilo encounters the

beloved and embarks with her on a journey to celebrate their union. The

dreamworld appears to have diminished Polia’s resistance; receptive to

Poliphilo’s advances, the woman sets off to explain her former hesitations and

recent change of mind.

A sequence from Polia’s narrative: “a furious goddess crowned with a wreath of agnus castus, with an unstrung bow and empty quiver, who turned a frightful countenance on me, burning with the desire to wreak cruel vengeance”

Much like Nausicaa’s visitation by the goddess Athena in the opening of the Odyssey’s sixth rhapsody, Polia’s vision at the closing of Hypnerotomachia reaffirms the primacy of a patriarchal, civic order over the sovereignty of a female body. Unlike Nausicaa, however, who was chastised for the messiness hidden behind the ornate doors of her bedroom, Polia is forced to give up idealistic purity and embrace the disturbing disorder of Poliphilo’s world. This reversal becomes all the more pronounced considering how the tactility of Nausicaa’s messy trousseau gives way to fully fledged architectural pandemonium in Hypnerotomachia.

“Reader,

if you wish to hear briefly what is contained in this work, know that Poliphilo

tells that he saw remarkable things in a dream, hence he calls the work in

Greek words ‘the strife of love in a dream’. He represents himself as having

seen many ancient things worthy of memory, and everything that he says he has

seen, he describes point by point in the appropriate terms and in an elegant

style: pyramids, obelisks, huge ruins of buildings.” With these words,

Francesco Colonna introduces his Hypnerotomachia Poliphili in 1499, at the

closing of the age of the incunabulum. A Dominican friar living in Venice, he

waited for thirty years before his manuscript, completed in 1467, was published

by Aldus Manutius. This was partially due to the cost of the undertaking, for

the volume, together with its 174 woodcuts by an anonymous artist, was one of

the most extravagant publishing ventures of its day. English readers have had

to wait a lot longer, until this 1999 edition that appears exactly 500 years

after the entry of Hypnerotomachia Poliphili into the Renaissance literary

canon.

Often

mentioned as one of the most handsomely produced books in the Renaissance, the

first edition of Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is exceedingly rare. Many surviving

copies have been mutilated by readers wishing to possess some of its opulently

designed woodcuts. It is, therefore, all the more rewarding that the present

publication attempts to convey the beauty of the original by adhering to its

size, as well as to the layout of the text and the images. Adding to the appeal

of this English edition for bibliophiles is its typeface, favored by Aldus

Manutius and known by modern printers as “Poliphilus.”

Indispensable

to any study of the Renaissance obsession with the lost world of Antiquity, Hypnerotomachia

Poliphili is more admired than actually read. Part of the reason for this is

the notorious difficulty of the original language, a fanciful linguistic idiom

based on Latin vocabulary and Italian morphology and syntax, challenging even

for Colonna’s contemporaries. A labor of love for Joscelyn Godwin, this

translation follows his earlier forays in the intellectual history of the early

modern world, most notably his publications on the seventeenth-century

philosophers Robert Fludd and Athanasius Kircher.

The

story—ostensibly a retelling of a long and involved dream that takes Poliphilo

through a landscape filled with ruins, tablets with inscriptions and

hieroglyphs, and other magnificent or curious remnants of Antiquity—is both

autobiographical and allegorical. Like Dante and his Beatrice, or Petrarch and

his Laura, Poliphilo pursues an ideal lover, a nymph by the name of Polia. And,

like these illustrious examples, he is doomed to lose her at the moment of

their closest embrace, as her body disappears into the air, ending both his

dream and his book. While the exact meaning of this symbolic account is as

elusive as Poliphilo’s pursuit, the author hints at his allegorical intent

throughout, beginning with the names of the two main protagonists. That

Poliphilo (literally “the lover of Polia”) is his alter-ego, is suggested by

the closing words of the nymph in which she calls him a “column of her life”

(Italian “Colonna”). Polia’s own name, deriving from the Greek term for “old

age” or "antiquity, " is generally understood as a hermeneutical key

to the overall theme of this dream-book.

Like its

language, the literary genre of Hypnerotomachia Poliphili is truly a hybrid

one, combining the conventions of romance, travelogue, and antiquarian treatise

in an ever-changing narrative. To follow Poliphilo’s descriptions of the

temples and monuments encountered on his imagined journey is to delve into an

assemblage of favorite Renaissance topoi. At the same time, this learned fabric

is interwoven with passages detailing his desire for Polia, whose undisguised

eroticism brings to mind the popular contemporary literature of a more

lascivious bent. In this manner, as stressed in the dedicatory preface to the

1499 edition, he fashioned a book for many audiences, a cornucopia of knowledge

that could rival the work of the ancients, and be presented with a pleasing

grace and novelty.

Notwithstanding

its textual eccentricity, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili has had a rich pictorial

and literary legacy. Mantegna, Titian, Lotto and Bernini, to name but a few of

the artists it inspired, eagerly drew upon its opulent, often enigmatic

imagery. Equally important was the impact of this volume on emblem books, the

principal vehicle for the dissemination of visual and poetic tropes in the

seventeenth century. From Alciatus and Valeriano, to lesser known authors such

as the Antwerp poet Jan van der Noot, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili was a favorite

sourcebook of Renaissance commonplaces.

Though

its publishing history prior to 1999 includes a number of translations, most of

them are abbreviated versions of the original. Notable among them, at least in

terms of the wider circulation of the text in Europe in the century following

its writing, was the 1546 French edition: Hypnerotomachia, ou, Discours du

Songe de Poliphile. The first and only attempt to translate this work into

English before Godwin was made in 1592, as Hypnerotomachia The Strife of Love

in a Dreame (London, Simon Waterson). Thwarted by the scope of the undertaking,

the translator R.D. (usually identified as Sir Robert Dallington, a courtier

and man of letters), stopped about two fifths into the text, leaving the

English readers for the next few centuries with a little more than a foretaste

of Colonna’s fertile imagination.

In the

brief and excellent introduction to the present edition, Godwin notes that his

translation project would have been a lot more difficult without the critical

edition of Hypnerotomachia Poliphili by Giovanni Pozzi and Lucia A. Ciapponi

(Padua: Editrice Antenore, 1968, reprinted in 1980 with a new Preface and

Bibliography). Unlike that scholarly volume, he intended this translation for a

more general audience interested in the culture of the Renaissance. As he

observes further, while he tried to preserve the spirit of Colonna’s literary

style, he knew that by rendering it in plain, standard English, he would

inevitably lose some of its linguistic wit.

Notwithstanding

this recognition of the limits of any translation, Godwin proves himself a

skillful interpreter of Colonna’s eccentric language. Thus, when Poliphilo

ventures to describe the physical charms of Polia, his words resonate with the

Renaissance poetics of praise of beautiful women, sensitively captured in

Godwin’s translation. Polia’s tresses are “filaments of gold with a changeable

lustre” ( subtilissimi fili d’oro inconstantemente rutilanti), her “festive and

radiant eyesπ are fit to turn Jupiter into a rain of gold” (festevoli et

radiosi ochii, da fundere Iove in piogia d’oro), while her cheeks, “fresh roses

gathered at dawn and placed in vases of purest Cypriot crystal” (fresche rose

alla surgente aurora collecte, et dopoi tra vasi di mundissimo crystalo de

Cypri) (145).

This

rhetoric of desire is even more pronounced in the author’s accounts of ancient

ruins, each one a document of the continuous struggle between Culture and the

implacable forces of Nature. Standing at a “great ruin of walls and enclosures”

(vastitate magna di muri o vero parieti) Poliphilo observes fissures filled

with “salt-loving littoral cock’s crestπsaltwort and fragrant sea-wormwoodπ”

(alcuni lochi vidi il literale cachile et molto kali et lo odoroso abscynthio

marino) (236). At another such edifice, he marvels at “the fragments of holy

antiquity” (gli fragmenti dilla sancta antiquitate) and wonders what their

effects would be “were they whole” (quanto farebbe la sua integritate) (59).

To

render Hypnerotomachia Poliphili in an English version approximating the

hermetic density of the language of the original would have required

philological acrobatics of doubtful merit for readers. Godwin illustrates this

point by comparing two passages, the first of which is a “more faithful”

translation of Colonna’s description of a Fury: “In this horrid and cuspidinous

littoral and most miserable site of the algent and fetorific lake stood

saevious Tisiphone, efferal and cruel with her viperine capillament, her

meschine and miserable soul, implacably furibund.” As we turn to the “plain”

English of the actual translation, we find a welcome respite whose deviance

from the original is more a blessing than a loss: “On this horrid and

sharp-stoned shore, in this miserable region of the icy and foetid lake, stood

fell Tisiphone, wild and cruel with her vipered locks and implacably angry”

(249).

Godwin

may have sacrificed some of Colonna’s linguistic craftsmanship, but he has

certainly shown a great sensitivity towards Colonna’s imagination and mastery

of tropes. In page after page of this expansive and convoluted dreamscape, he

succeeds in imparting the poetic exuberance of the original to the modern

reader. Even if Godwin intended this translation for a number of different

readers, it will undoubtedly rekindle the interest of art historians in this

famous, if still insufficiently explored monument to the Renaissance

infatuation with Antiquity.

Hypnerotomachia

Poliphili: The Strife of Love in a Dream. By Aneta Georgievska-Shine. CCA.Reviews, June 16, 2000.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Hypnerotomachia, by Francesco Colonna. Translated

by Robert Dallington, 1969.

No comments:

Post a Comment