Someday,

people with penises will gestate foetuses. I am speculating, of course, but not

wildly. If babies can be conceived in a test tube, that is, if we can amend the

erstwhile rules of reproductive biology this way, why can’t people with penises

gestate foetuses, lactate, and do other things associated exclusively with the

uterine body? We’re used to the idea that physiological differences dictate rigidly

different ways of participating in sexual reproduction. Or at least, that’s the

way it’s been so far.

As more

and more people are recognising today, biology and sex turn out to be a lot

less fixed than we might have once thought. And, importantly, politics is

involved in how much our understanding of biology, sex and gender can and

should change – and the direction of change.

Commonplace

notions of biology and sex continue to influence what we take as natural and

given, including the belief that men don’t get pregnant. (And as important as

it is to point out that trans men can get pregnant, I am addressing a rather

different set of challenges in this essay.) A question I often ask my students

in a class on gender and science is this: how many effective and widely

available new forms of birth control have been developed in the past 100 years

for men? It’s a safe assumption that my captive audience is in the first years

of learning about and utilising contraception. Why had so few considered this

situation unfair and overly burdensome on women? Why was there still no easily

accessible kind of artificial birth control for men other than the condom,

which after all has been around in one form or another for at least hundreds of

years?

They

knew why, because we all know why: no matter how much we talk about gender

equality, the implicit assumption often ends up being that men and women are,

deep down, different. Only people with female reproductive organs get pregnant,

and somehow this has come to mean that women should be more responsible for

contraception. Or at least that’s the unspoken belief of many, despite the fact

that no one with female reproductive organs ever got pregnant without help from

someone with male reproductive organs.

We still

live in an age of the gender binary, but it’s also a time of mass gender

confusion, debate and renegotiation disputing the gender binary. And that’s a

great thing. Assumptions and shibboleths about gender (and sex and sexuality)

are being defended and challenged, and language is being recast – think about

the sudden transformations of pronouns people are using to refer to themselves.

Language matters, and with respect to gender and sexuality I have come to the

conclusion that we need to be very careful indeed when we make unwarranted

comparisons about common ‘male’ and ‘female’ traits among humans and nonhuman

animals. Among other things, there is a whole lot of exaggerated

anthropomorphism that tickles our curiosities and satisfies our quixotic

yearnings but reinforces erroneous stereotypes about male and female.

Among my

favourite examples are prostitute hummingbirds, baboon harems, and mallard duck

gang rape.

Some wit

thought that when male and female hummingbirds have sex, and the male ‘gives’

something, like a twig for a nest, to the female, the male is in effect paying

the female for sex. And that’s what prostitution is all about, isn’t it? The

idea that sex work involves a complex network of relationships, and that humans

who have sex can also give each other presents without this in itself

constituting sex work, is apparently not relevant here. The point is that males

pay females for sex (and that this payment is the only reason females allow

males to have sex with them), and that there are strong enough cross-species

similarities to justify such language flourishes.

When I

was young and just learning about sex, I learned about something called a

harem. It was an arrangement in some other parts of the world, we thought,

where a man could have many wives, and have sex with any one of them he chose.

We believed that, if one wife didn’t want to have sex, there would always be

another available. So, it’s not strange perhaps that virtually every

primatologist who has ever spent the night on a savannah with a troop of

baboons has resorted to the shorthand description of ‘harem’ to describe a

situation in which one male mates with many females. Not to get too

anthropologically nit-picky, but I must object: in dozens of papers and books I

have read by these primatologists, I have yet to come across one sentence

about, much less a fuller description of, an actual human harem, the cultural

and social contexts in which they are found, the agency of females as well as

males in these relationships, or any aspect of volition and choice in such

arrangements. An adolescent fantasy seems to be the most likely explanation for

this salacious anthropomorphism about harems among baboons.

Finally,

the matter of mallard ducks and the fact that perhaps 40 per cent of

copulations are coerced, an activity that has been called ‘gang rape’ of a

solitary female. Even calling this conduct ‘forced copulation’, which might be

considered a step in the right direction, still lands us in semantic quicksand,

erroneously confusing what is routine behaviour that leads to impregnating the

female duck with the actions of human males who consciously decide to sexually

attack a female. It also implies that female humans and female ducks are

comparatively the same, passive victims and receptacles of male aggression and

sexual predation. (For a brazen invocation of the mallard duck gang-rape

thesis, see David Barash’s book Sociobiology: The Whisperings Within (1980);

for a detailed and thorough takedown of the thesis, see Richard O Prum’s

prizewinning book The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin’s Forgotten Theory of

Mate Choice Shapes the Animal World – And Us (2017).)

It

matters what language we use to describe and explain human behaviour such as

prostitution, harems and gang rape, among other things, because it gets to the

gist of how ‘animal’ we are: how much we share in common with other animals;

how much we have control over our actions; what are fundamental, hardwired (or

genetically programmed, evolutionarily driven, chromosomally relevant)

differences between male and female humans that relate, for example, to

sexuality and aggression; the extent to which the males of all species and the

females of all species share some fundamental features in common and, if so,

what they are; and which allegedly cross-species male attributes represent a

relic of outmoded social values more than anything anatomical.

Let’s

consider the 220 million cats and 200 million dogs (and counting) worldwide

that we call our pets: how often do we bestow them with human names? How often

do we compare their personalities with those of friends or family? We humanise

nonhuman animals. And, pretty easily, we extend this line of thinking to

humanise nonhuman animal behaviour. We animalise humans, which really means we

dehumanise humans, making their actions and desires products of inherited

traits more than conscious decision-making and volition. Some have even argued

that the role of society is exactly to tame and restrict these supposedly

innate, mammalian instincts in humans. As the anthropologist and primatologist

Agustín Fuentes wrote in Race, Monogamy, and Other Lies They Told You (2012):

‘It’s a commonly held belief that if you strip away culture, that which keeps

us well behaved, then a beastly savage will emerge (especially in men).’

In one

of my classes I teach about gender and science, I have used the examples of

hummingbird prostitutes, baboon harems and mallard duck gang rape. A week after

we discussed how such anthropomorphism could lead to woefully incorrect

understandings about human sexuality, a student returned with the following

anecdote: she had just heard a lecture in her biology class in which the

professor used the phrase ‘gangbanging bacteria’. Not even animal gangbanging

in this instance! Amusing or alarming?

Although

the term ‘toxic masculinity’ has captured the imaginations of many people who

want to call attention to men thinking and acting in ways that are harmful to

others, male and female, it is also problematic. Because, if you believe that

someone who identifies as male can act only within a range of masculinities,

and by definition everything they do is on a masculinity continuum of some

kind, you are still stuck in a very binary world. Would it make sense to talk

about the toxic masculinity of certain male hummingbirds and ducks? Yet ideas

about males-of-all-species often lie just beneath the surface of contemporary

discussions about the gender binary and, indeed, widespread discussions and

debates regarding gender and sexuality.

Efforts

in recent years to dismantle neat male-female models have been met with stiff

resistance in both religious and scientific quarters. Evolutionary biologists,

for instance, have argued vociferously that male-female differences with

respect to sexuality and aggression are core components of what it means to be

human and animal in general. Among the theological responses to challenges to

the gender binary we find one from 2019, when the Vatican published ‘“Male and

Female He Created Them”: Towards a Path of Dialogue on the Question of Gender

Theory in Education’, written by Cardinal Giuseppe Versaldi and Archbishop

Angelo Vincenzo Zani. Apparently, the Vatican had decided that gender confusion

among its 1.2 billion parishioners worldwide had reached epidemic proportions.

Their ‘Male and Female’ paper faithfully endorses the gender binary as

God-given, and cautions that any and all notions of gender bending go against

not only God but also modern medicine and science.

By

censuring anthropology’s examination of gender and sexual indeterminacy as too

relativist, and asserting that male and female bodies and temperaments are

fundamentally unalike, the gender binary gets sanctified as reality, and it

becomes easier to attribute every form of male behaviour – including those related

to sexuality and aggression – to the natural, unchangeable world.

This is

a time of gender confusion and instability as to what the connection is between

physiology and temperament, especially when it comes to male and female.

Efforts to delink aggression from something that is considered

characteristically and particularly male – in effect, to de-gender our concept

of aggression – must inevitably contend with the gender binary. And this is

threatening to those with a vested interest in maintaining a view of the world

in which perceptions about our biology, and our evolutionary heritage, are

reduced to ageless Mars/Venus frameworks.

Yet

objections to the gender binary view of the world have implications far beyond

spiritual disputes, beyond how many credible parallels we can draw regarding

engendered behaviour in humans and, for example, monkeys. Monkey see, human do?

Biological extremism gets us into trouble repeatedly, many times without us

even realising that our assumptions about differences are based on little more

than common sense.

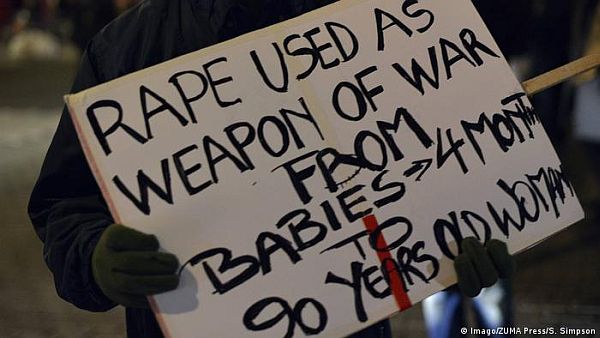

Although

most discussions about rape don’t involve mallard ducks, references to ‘rape’

in the nonhuman animal kingdom surely resonate with the idea that there is

something natural about rape across species, and therefore that it is, at most,

possible to control among humans, but never eradicate, because it is

biologically baked in. Thus do we pathologise maleness and reduce public policy

to restraining males’ ‘natural’ impulses.

The

leading anthropologist of gender and violence Sally Engle Merry has underscored

the ease with which the criminalisation of gender-based violence – in her

study, spouse abuse in Hilo, Hawai‘i – is naturalised. Husbands beating wives

is treated by the courts in Hilo as ‘natural to men’, while men attending

state-mandated programmes ‘discover that the authority of the court is

exercised against their customary control over women and that their “natural”

behaviours are penalised.’

Half a

world away, Maria Eriksson Baaz and Maria Stern conducted research on why vast

numbers of male soldiers raped women during the war in the Democratic Republic

of the Congo (DRC) in the 1990s and 2000s that killed more than 5 million

people. Interviewing officers and soldiers, men and women, these scholars were

repeatedly told that there had been two kinds of rape in the DRC: ‘lust rape’

and ‘evil rape’. Male sexual needs caused lust rapes; evil rapes were triggered

by men’s need to destroy. Lust rapes were directly linked to the sexual

deprivations of wartime.

We place

unreasonable trust in biological explanations of male behaviour. Nowhere is

this truer than with testosterone. Contemporary pundits invoke the hormone

nicknamed ‘T’ to prove points about maleness and masculinity, to show how

different men and women are, and to explain why some men (presumably those with

more T) have greater libidos. Yet, despite the mythic properties popularly

associated with T, in every rigorous scientific study to date there is no

significant correlation in healthy men between levels of T and sexual desire.

Beginning

in the 1990s and really picking up steam in the 2000s, sales of testosterone

replacement therapies (TRTs) went from practically zero to over $5 billion

annually in 2018. This was either because there was a sudden outbreak of ‘Low

T’ when a major medical epidemic was finally recognised, or because T became

marketed as a wonder drug for men thrown into a panic when they learned that

their T levels declined 1 per cent annually after they hit 30.

The

answer is not that men’s bodies changed or that Low T was horribly

underdiagnosed before but that, in the minds of many, T became nothing short of

a magic male molecule that could cure men of declining energy and sexual desire

as they aged.

What’s

more, many have been taught that, if you want to know what causes some men to

be aggressive, you just test their T levels, right? Actually, wrong: the

science doesn’t support this conclusion either. Some of the famous early

studies linking T and aggression were conducted on prison populations and were

used effectively to ‘prove’ that higher levels of T were found in some men

(read: darker-skinned men), which explained why they were more violent, which

explained why they had to be imprisoned in disproportionate numbers. The

methodological flaws in these studies took decades to unravel, and new rigorous

research showing little relation between T and aggression (except at very high

or very low levels) is just now reaching the general public.

What’s

more, it turns out that T is not just one thing (a sex hormone) with one

purpose (male reproduction). T is also essential in the development of embryos,

muscles, female as well as male brains, and red blood cells. Depending on a

range of biological, environmental and social factors, its influence is varied

– or negligible.

Robert

Sapolsky, a neuroscientist at Stanford University in California, compiled a

table showing that there were only 24 scientific articles on T and aggression

1970-80, but there were more than 1,000 in the decade of the 2010s. New

discoveries about aggression and T? No, actually, although there were new

findings in this period showing the importance of T in promoting ovulation.

There is also a difference between correlation and cause (T levels and

aggression, for example, provide a classic chicken-egg challenge). As leading

experts on hormones have shown us for years, for the vast majority of men, it’s

impossible to predict who will be aggressive based on their T level, just as if

you find an aggressive man (or woman, for that matter), you can’t predict their

T level.

Testosterone

is a molecule that was mislabelled almost 100 years ago as a ‘sex hormone’,

because (some things never change) scientists were looking for definitive

biological differences between men and women, and T was supposed to unlock the

mysteries of innate masculinity. T is important for men’s brains, biceps and …

that other word for testicles, and it is essential to female bodies. And, for

the record, (T level) size doesn’t necessarily mean anything: sometimes, the

mere presence of T is more important than the quantity of the hormone. Sort of

like starting a car, you just need fuel, whether it’s two gallons or 200. T

doesn’t always create differences between men and women, or between men. To top

it all off, there is even evidence that men who report changes after taking T

supplements are just as likely reporting placebo effects as anything else.

Still,

we continue to imbue T with supernatural powers. In 2018, a US Supreme Court

seat hung in the balance. The issues at the confirmation hearings came to focus

on male sexual violence against women. Thorough description and analysis were

needed. Writers pro and con casually dropped in the T-word to describe,

denounce or defend the past behaviour of Justice Brett Kavanaugh: one

commentator in Forbes wrote about ‘testosterone-induced gang rapes’; another,

interviewed on CNN, asked: ‘But we’re talking about a 17-year-old boy in high

school with testosterone running high. Tell me, what boy hasn’t done this in

high school?’; and a third, in a column in The New York Times, wrote: ‘That’s

him riding a wave of testosterone and booze…’

And it

is unlikely that many readers questioned the hormonal logic of Christine

Lagarde, then chair of the International Monetary Fund, when she asserted that

the economic collapse in 2008 was due in part to too many males in charge of

the financial sector: ‘I honestly think that there should never be too much

testosterone in one room.’

You can

find T employed as a biomarker to explain (and sometimes excuse) male behaviour

in articles and speeches every day. Poetic licence, one might say. Just a

punchy way to talk about leaving males in charge. Yet when we raise T as

significant in any way to explain male behaviour, we can inadvertently excuse

male behaviour as somehow beyond the ability of actual men to control. Casual

appeals to biological masculinity imply that patriarchal relationships are

rooted in nature.

When we

normalise the idea that T runs through all high-school boys, and that this

explains why rape occurs, we have crossed from euphemism to offering men

impunity to sexually assault women by offering them the defence ‘not guilty, by

reason of hormones’.

Invoking

men’s biology to explain their behaviour too often ends up absolving their

actions. When we bandy about terms such as T or Y chromosomes, it helps to

spread the idea that men are controlled by their bodies. Thinking that hormones

and genes can explain why boys will be boys lets men off the hook for all

manner of sins. If you believe that T says something meaningful about how men

act and think, you’re fooling yourself. Men behave the way they do because

culture allows it, not because biology requires it.

No one

could seriously argue that biology is solely responsible for determining what

it means to be a man. But words such as testosterone and Y chromosomes slip

into our descriptions of men’s activities, as if they explain more than they

actually do. T doesn’t govern men’s aggression and sexuality. And it’s a shame

we don’t hear as much about the research showing that higher levels of T in men

just as easily correlate with generosity as with aggression. But generosity is

less a stereotypically male virtue, and this would spoil the story about men’s

inherent aggressiveness, especially manly men’s aggressiveness. And this has a

profound impact on what men and women think about men’s natural inclinations.

We need

to keep talking about toxic masculinity and the patriarchy. They’re real and

they’re pernicious. And we also need new ways of talking about men, maleness

and masculinity that get us out of the trap of thinking that men’s biology is

their destiny. As it turns out, when we sift through the placebo effects and

biobabble, T is not a magic male molecule at all but rather – as the

researchers Rebecca Jordan-Young and Katrina Karkazis argue in their excellent

new book Testosterone (2019) – a social molecule.

Regardless

of what you call it, testosterone is too often used as an excuse for letting

men off the hook and justifying male privilege.

Testosterone

is widely, and sometimes wildly, misunderstood. By Matthew Gutmann. Aeon, March 10, 2020.

Matthew

Gutmann‘s Are Men Animals?: How Modern Masculinity Sells Men Short starts

promisingly. His premise is simple enough, but in that simplicity there are

some major problems. He writes: “I believe that the ways in which people think

about men and expect men to behave can be dramatically renegotiated.” It’s certainly

a compelling statement that’s hard to deny.

Unfortunately, there isn’t much provided in the way of how we can renegotiate these expectations. “Acting as if men can’t control themselves is hazardous,” he writes. He argues (not a hard position to take) that women are central to the lives of most men, and he looks at the origins of masculinity. There are myths and half-myths. Do men really spend less time in parental activities than women? Are there really no social structures on earth run by women?

Gutmann travels through Mexico and Shanghai to look at cultures of masculinity beyond US borders. He’s looking for clues, for counter-histories to write something different. His approach to the subject is effective to a point, but there’s no sense (even in these early pages) that the result of his work is unique.

Are men genetically pre-conditioned to commit sexual assault? Is rape and murder pre-destined and eventual because of destiny? Gutmann considers the notion that more such acts would occur if men thought they could get away with it, but this mixture of anthropological and gender studies clashing with a cursory look at the legal system is tough to swallow when it’s not done in equal parts. In his opening Chapter “Gender Confusion”, Gutman argues that The Human Genome Project of the ’90s was “…after eugenics, the second major push of the century for…’hereditarian scientific ideology.’ He asserts that the concept of “Gender Confusion” (aligning with traditional male roles of hunter and provider) is historical and cultural.

The problem here is simple. To propose we are “confused” about gender identity and social roles suggests that there is in fact a definite way to see men on their own and as reflected through their relationships with women. Gutmann continues to ask that we renegotiate what it means to be a man, but he leaves the reader at a loss by never proposing what that new masculine identity should be. By opening with a discussion on gender confusion, he implies that trans identity (which is given a very minor consideration in this book) is complicating rather than enhancing a progressive sense of gender fluidity.

Indeed, “The Science of Maleness” chapter has some problematic conclusions. In particular, Gutmann proposes that aggression elevates testosterone secretion, not the other way around. He proposes that murderers are predominantly men (“…about nine men commit murder for every one woman…”), and he indicates that some researchers have simply surrendered to the idea that men are, by and large, destined to murder. It’s an interesting notion, but once again he seems to contradict himself by noting “…most men never kill or even commit assault.”

The problem here is that Gutmann introduces these ideas but he doesn’t fully explore them, as the informed reader would hope to happen. Does he believe men are doomed? Gutmann’s argument is strongest when he makes his connections between human and animal males. Are we all that similar? He writes: “The words we use and the meanings behind them influence how we understand human relationships and events.”

Later, he makes a strong argument about the way we are as a species and how we can be better: “Humans don’t have to act like other animals…To lose sight of human mutability and the range of behavior among humans is to give men a morphological free pass to tyrannize others under the guise of ‘acting like a guy.'”

Gutmann carefully brings us through men’s libidos and natural aggressions. Why do men make war? He draws connections between the fact that sex workers of The Dominican Republic were used to satiate the sexual compulsion of UN Peacekeeping forces and the inherent male trait for aggression. Is rape really “…rooted in a feature of human nature,” as proposed by psychologist Steven Pinker? Gutmann introduces these ideas and then shuts them down: “Men’s bodies are biologically no more or less choosy, coy, or capricious than women’s.”

This is a long chapter that could very well have been expanded to better purposes, especially when he includes Donald Trump (not by name, but we all know the story) in his example of “Bad” violence and “Good” violence. He re-prints the transcript of Trump’s famous “Grab ’em by the pussy” interview with Access Hollywood and asserts that the greatest sin here was not that Trump said these words. Instead, there was “…complicity in the acquiescence, and that collusion was rooted in bedrock beliefs about men and women and violence.” In other words, the nation got what it wanted when it voted for him, and there is nobody to blame but ourselves for the consequences.

The more interesting and effective chapters are set in Mexico and China. Regarding the latter, “Reverting to Natural Genders in China” looks at Shanghai’s Blind Date Corner, where aged parents meet with matchmakers to offer their children as prospective mates. This is a place where “…the intellectual and career accomplishments of daughters are generally included on their flyers, along with their physical attractiveness. Men’s flyers list their height, professional trajectory, and whether they can already provide housing…” The argument is that there are three genders in China, and their third gender is women with PhDs. Gutman adds: “It didn’t take long before a fourth gender was added: men married to women with PhDs.

“Biology can’t be changed, and it won’t matter (as Gutmann notes about Mexico) if the transit system offers gender-segregated train cars to eliminate (or cut down on) crimes against women. Gutmann seems to rush through other issues in the later chapters: pronoun choices, Bret Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination case, and the all-pervasive truth of “toxic masculinity”. It’s a whirlwind of issues that Gutmann presents, but the volume of material should not be perceived as a comprehensive answer to whether or not men are animals.

“If we accept that violence is a core feature rather than a flaw of male behavior, and that assault is men’s essential nature reasserting itself, we cripple our ability to identify and combat misogyny, gender bias, and discrimination.” It’s hard to dispute this, but the rushed sense of this book’s final third gives the impression that Gutmann preferred to stuff his text with ideas and perspectives that would please all sides. Had he been more brave and emphasized the political consequences of toxic masculinity, this could have been a stronger book, even incendiary, as we all wait a possible second Trump presidency, where the worst aspects of manhood (primitive, predatory, animalistic) are elevated and rewarded.

The ground Gutmann walks throughout these pages is flat and wide, well-worn by those who came before him. He’s not forging any new paths here that can’t be accessed through deeper texts, different texts. Testosterone: An Unauthorized Biography by Rebecca M. Jordan-Young and Katrina Karkazis, and Stephen Pinker’s The Better Angels of our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined that have done a better job looking at the nature of violence and masculinity as expressed by men.

There is sound and solid research to be found about the way men are perceived in Mexico and China, but Gutmann’s questions on gender identity are problematic. His presumption that there is a definitive notion of masculinity hurts this book’s potential to make a major difference. Most of us can already answer the title’s question: Yes, men are indeed animals, “modern masculinity” is fluid and therefore not as lethal as he might assume, and we can raise ourselves up higher if we accept these truths.

Unfortunately, there isn’t much provided in the way of how we can renegotiate these expectations. “Acting as if men can’t control themselves is hazardous,” he writes. He argues (not a hard position to take) that women are central to the lives of most men, and he looks at the origins of masculinity. There are myths and half-myths. Do men really spend less time in parental activities than women? Are there really no social structures on earth run by women?

Gutmann travels through Mexico and Shanghai to look at cultures of masculinity beyond US borders. He’s looking for clues, for counter-histories to write something different. His approach to the subject is effective to a point, but there’s no sense (even in these early pages) that the result of his work is unique.

Are men genetically pre-conditioned to commit sexual assault? Is rape and murder pre-destined and eventual because of destiny? Gutmann considers the notion that more such acts would occur if men thought they could get away with it, but this mixture of anthropological and gender studies clashing with a cursory look at the legal system is tough to swallow when it’s not done in equal parts. In his opening Chapter “Gender Confusion”, Gutman argues that The Human Genome Project of the ’90s was “…after eugenics, the second major push of the century for…’hereditarian scientific ideology.’ He asserts that the concept of “Gender Confusion” (aligning with traditional male roles of hunter and provider) is historical and cultural.

The problem here is simple. To propose we are “confused” about gender identity and social roles suggests that there is in fact a definite way to see men on their own and as reflected through their relationships with women. Gutmann continues to ask that we renegotiate what it means to be a man, but he leaves the reader at a loss by never proposing what that new masculine identity should be. By opening with a discussion on gender confusion, he implies that trans identity (which is given a very minor consideration in this book) is complicating rather than enhancing a progressive sense of gender fluidity.

Indeed, “The Science of Maleness” chapter has some problematic conclusions. In particular, Gutmann proposes that aggression elevates testosterone secretion, not the other way around. He proposes that murderers are predominantly men (“…about nine men commit murder for every one woman…”), and he indicates that some researchers have simply surrendered to the idea that men are, by and large, destined to murder. It’s an interesting notion, but once again he seems to contradict himself by noting “…most men never kill or even commit assault.”

The problem here is that Gutmann introduces these ideas but he doesn’t fully explore them, as the informed reader would hope to happen. Does he believe men are doomed? Gutmann’s argument is strongest when he makes his connections between human and animal males. Are we all that similar? He writes: “The words we use and the meanings behind them influence how we understand human relationships and events.”

Later, he makes a strong argument about the way we are as a species and how we can be better: “Humans don’t have to act like other animals…To lose sight of human mutability and the range of behavior among humans is to give men a morphological free pass to tyrannize others under the guise of ‘acting like a guy.'”

Gutmann carefully brings us through men’s libidos and natural aggressions. Why do men make war? He draws connections between the fact that sex workers of The Dominican Republic were used to satiate the sexual compulsion of UN Peacekeeping forces and the inherent male trait for aggression. Is rape really “…rooted in a feature of human nature,” as proposed by psychologist Steven Pinker? Gutmann introduces these ideas and then shuts them down: “Men’s bodies are biologically no more or less choosy, coy, or capricious than women’s.”

This is a long chapter that could very well have been expanded to better purposes, especially when he includes Donald Trump (not by name, but we all know the story) in his example of “Bad” violence and “Good” violence. He re-prints the transcript of Trump’s famous “Grab ’em by the pussy” interview with Access Hollywood and asserts that the greatest sin here was not that Trump said these words. Instead, there was “…complicity in the acquiescence, and that collusion was rooted in bedrock beliefs about men and women and violence.” In other words, the nation got what it wanted when it voted for him, and there is nobody to blame but ourselves for the consequences.

The more interesting and effective chapters are set in Mexico and China. Regarding the latter, “Reverting to Natural Genders in China” looks at Shanghai’s Blind Date Corner, where aged parents meet with matchmakers to offer their children as prospective mates. This is a place where “…the intellectual and career accomplishments of daughters are generally included on their flyers, along with their physical attractiveness. Men’s flyers list their height, professional trajectory, and whether they can already provide housing…” The argument is that there are three genders in China, and their third gender is women with PhDs. Gutman adds: “It didn’t take long before a fourth gender was added: men married to women with PhDs.

“Biology can’t be changed, and it won’t matter (as Gutmann notes about Mexico) if the transit system offers gender-segregated train cars to eliminate (or cut down on) crimes against women. Gutmann seems to rush through other issues in the later chapters: pronoun choices, Bret Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination case, and the all-pervasive truth of “toxic masculinity”. It’s a whirlwind of issues that Gutmann presents, but the volume of material should not be perceived as a comprehensive answer to whether or not men are animals.

“If we accept that violence is a core feature rather than a flaw of male behavior, and that assault is men’s essential nature reasserting itself, we cripple our ability to identify and combat misogyny, gender bias, and discrimination.” It’s hard to dispute this, but the rushed sense of this book’s final third gives the impression that Gutmann preferred to stuff his text with ideas and perspectives that would please all sides. Had he been more brave and emphasized the political consequences of toxic masculinity, this could have been a stronger book, even incendiary, as we all wait a possible second Trump presidency, where the worst aspects of manhood (primitive, predatory, animalistic) are elevated and rewarded.

The ground Gutmann walks throughout these pages is flat and wide, well-worn by those who came before him. He’s not forging any new paths here that can’t be accessed through deeper texts, different texts. Testosterone: An Unauthorized Biography by Rebecca M. Jordan-Young and Katrina Karkazis, and Stephen Pinker’s The Better Angels of our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined that have done a better job looking at the nature of violence and masculinity as expressed by men.

There is sound and solid research to be found about the way men are perceived in Mexico and China, but Gutmann’s questions on gender identity are problematic. His presumption that there is a definitive notion of masculinity hurts this book’s potential to make a major difference. Most of us can already answer the title’s question: Yes, men are indeed animals, “modern masculinity” is fluid and therefore not as lethal as he might assume, and we can raise ourselves up higher if we accept these truths.

Do We

already know the Answer to the Question, Are Men Animals? By Christopher John

Stephens. Pop Matters, 20 February 2020

How Much Are Men Ruled By Biology?

No comments:

Post a Comment