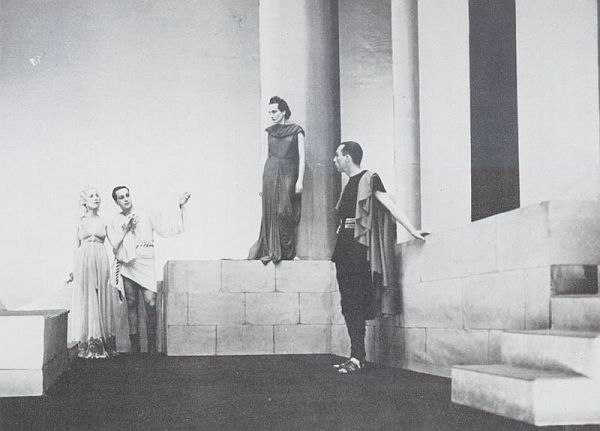

A dancer (left) with choreographers Martha Graham and Erick Hawkins, New York, 1946.

For

Rachel Bespaloff, philosophy was a sensual activity shaped by the rhythm of

history, embodied in an instant of freedom

Shortly after Rachel Bespaloff’s suicide in 1949, her friend Jean Wahl published fragments from her final unfinished project. ‘The Instant and Freedom’ condensed themes that occupied the Ukrainian-French philosopher throughout her life: music, rhythm, corporeality, movement and time. One of Bespaloff’s key ideas, ‘the instant’, is less a fragment of duration than a life-changing event, a moment of embodied metamorphosis. In the midst of a noisy world, torn between transience and eternity, the human being listens to the sound of history. Had she completed and published it, ‘The Instant and Freedom’ might have become the masterpiece of an important early existentialist thinker. Instead, her name is hardly mentioned today.

Yet Bespaloff was a brilliant and original thinker, among the first wave of existentialists in France. Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre and Gabriel Marcel all admired her. A professional dancer and choreographer, she had finely tuned ears for the musicality of philosophical writing. For Bespaloff, philosophy is a dynamic, sensual activity of listening to and engaging with the voices of others, including those long dead. In dialogue with Homer, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and Heidegger, she found her own voice. At the heart of Bespaloff’s world is an original conception of time shaped by embodiment and music: the instant is a silent pause that suspends history’s repetitive rhythm. Through our bodies, we experience that break from history as a brief moment of freedom.

Her more famous contemporary Simone Weil also used her body to express her philosophy: Weil eventually starved herself to death in solidarity with friends and compatriots in occupied France. Bespaloff shared Weil’s interest in attention, listening and waiting as mystical practices of the body. For both thinkers, philosophy was an existential embodiment of their ideas. However, Bespaloff did not use her body as a weapon against itself; rather, she was interested in dance as a creative alchemy of movement. Bespaloff’s philosophy of the body is closely linked to the experience of time: it is our embodied day-to-day existence that measures and gives rhythm to time. In an essay on Homer’s Iliad written during the Second World War, Bespaloff captured the experience of living through the horrors of exile and war. The human being, ‘bound to her time by disorder and misfortune, acquires a new perception of the time of her own existence.’ (All translations here from the French are my own.)

Bespaloff’s own life was one of repeated displacement: she moved from Ukraine to Switzerland, Paris to southern France, to Mount Holyoke via New York. Born in 1895 in Nova Zagora in Bulgaria to a Ukrainian-Jewish family, she spent her childhood in Kyiv and then in Geneva where the family moved in 1897. Her mother Debora Perlmutter was a philosopher who taught at university; her father, Daniel Pasmanik, a surgeon, became a leading theoretician of Zionism in the Russian Empire. A fervent anti-Bolshevik, Pasmanik fought for the White Army in the Russian Civil War. In Switzerland, Bespaloff (then Rachel Pasmanik), studied piano and composition at the conservatory, philosophy at the university, and eurythmics with Émile Jaques-Dalcroze. These three areas of study are all entwined in her existential philosophy of embodiment.

Dalcroze eurhythmics is a holistic method of musical education; it turns the body into an instrument. Different temporalities are concretised through movements, arm gestures and steps. For Bespaloff, eurythmics became an intimate practice of listening with her entire body. Dalcroze’s favourite student, she was sent to work in Paris in early 1919. She began teaching eurythmics at the Paris Opera while also publishing short texts on dance. Bespaloff’s ‘plastic dance’ aimed to restore a lost dynamism. Her method attracted the attention of Jean Cocteau and Sergei Diaghilev, who introduced this new corporeality to his Ballets Russes. If philosophy sharpened her ears, eurythmics sculpted her body towards an embodied experience of temporality. She believed that a more authentic sense of time, lost in modernity, still lurked beneath our skin.

In 1921, Bespaloff was the choreographer of the ‘Royal Hunt’ scene in Hector Berlioz’s opera The Trojans – a theme she would return to in her Iliad essay. In ‘Dance and Eurythmics’ (1924), Bespaloff wrote that dance is a universe with ‘its vocabulary, a fixed language, its own logic, its needs.’ Eurythmics is the system of this universe, turning movement into existential experiences. Through the plasticity of our bodies, we can reach new forms of being. In the fragment ‘The Dialectic of the Instant’, Bespaloff describes time consciousness as ‘nothing other than a certain way of grasping the relationship between finitude and infinity in the instant.’ The instant’s brevity points us towards a lost continuity that can be restored. Through music and dance, Bespaloff discovered what she calls the experience of ‘magic interiority’. By externalising movement, the subject of eurythmics plunges herself into an inner experience.

Bespaloff met her second important teacher in 1925, the Jewish existentialist philosopher Lev Shestov (born in Kyiv as Yehuda Leib Shvartsman). The encounter with Shestov changed her life: Bespaloff the choreographer decided to become a philosopher. This was a radical move but, by then, she was already married to a Ukrainian businessman, which allowed her to quit her job at the Opera and soon after have a daughter. Shestov was a central figure in the philosophical émigré circles of interwar Paris. French existentialism gained fame much later through the works of Sartre and Camus. However, Sartre was deeply indebted to Shestov’s original synthesis of Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky and Jewish theology.

Shestov’s charisma and unsystematic thought magnetised young philosophers, among them Georges Bataille. In many ways, the Shestov circle was the hotbed of French existentialism. Along with the Romanian poet Benjamin Fondane, Bespaloff was at the centre of Shestov’s salon. Her friend Daniel Halévy described her sitting on Shestov’s sofa, completely motionless, while ‘she listened with her whole person: with her hands, with her lips, with her eyes.’ One of the few women in the circle, she soon became friends with the Christian existentialist writer Gabriel Marcel and the Jesuit theologian Gaston Fessard who both admired her work. A female philosopher in the 1930s was, as Olivier Salazar-Ferrer put it, ‘a bit like a woman in the 19th century wearing men’s clothes.’ However, Bespaloff would soon wear her own clothes. In 1929, she had dinner with Edmund Husserl whose phenomenology she confidently attacked with Shestovian arguments.

Bespaloff caused another stir with the publication of her ‘On Heidegger (Letter to Daniel Halévy)’ in La Revue philosophique in 1933. It was among the very first discussions of Martin Heidegger’s thought in France. Fluent in German, Bespaloff had read Heidegger’s Being and Time (1927) in the summer of 1932. Heidegger’s greatness, she wrote, was that ‘he situates himself in the inextricable; he does not want to detach himself.’ Similar to the experience of eurythmics, Heidegger’s philosophy proposes our hopeless entanglement with the world. It is not difficult to imagine a 28-year-old Sartre being drawn to Bespaloff’s letter, where she wrote excitedly: ‘Existence projects itself into the possible: choice is its destiny.’ For Bespaloff, interpreting Heidegger, this choice is not a matter of free will but of irrevocable commitment. By actively choosing, we dash beyond ourselves into an uncertain future.

As a musician, Bespaloff ‘listened’ to Heidegger’s text as if to a performance of Bach, a ‘monumental Art of Fugue’. She recognised that, as in a Baroque fugue, all the motifs ‘bring us back to the central theme of Being taken up in all its possible aspects, with increasing infinite variation, but always identical to itself.’ Bespaloff’s enthusiasm for Heidegger’s musical metaphysics was soon tempered by the discovery of another existentialist: Søren Kierkegaard. In 1934, she published notes on Kierkegaard’s Repetition (1843), a work that emphasised the musicality of repetition as continuous transformation.

Repetition does not add anything, it only accentuates what is irreducible to human existence. Repetition in Kierkegaard is ‘the will to live again and the refusal to survive’. Only by repeating can we become authentic subjects. In Kierkegaard’s ‘beautiful moment’, Bespaloff found what she called ‘the instant’: an experience of absolute, eternal silence. The absence of a path, she wrote on Kierkegaard, is the only path his philosophy wants to follow. This Zen-like image also perfectly captures the meandering trajectories of her own thought, which Laura Sanò has called ‘nomadic’. A wandering cosmopolitan, Bespaloff was forced to traverse the boundaries of various countries, languages and cultures. Her philosophy mirrored that nomadism, with subtle attention to the embodied experience of movement, melody and metamorphosis.

Bespaloff’s essay collection Paths and Crossroads (Cheminements et Carrefours) appeared in 1938. Dedicated to Shestov, the book includes texts on Julien Green, André Malraux, Marcel and two essays on Kierkegaard. The chapter ‘Shestov before Nietzsche’ declares war on her teacher’s total denial of any possibility of truth. By refusing to think, she writes, Shestov had returned to another dogma – a radical relativism that ultimately turned into nihilism. Against Shestov’s rejection of reason, Bespaloff poses Nietzsche’s attempt to reach truth through and within one’s life. Nietzsche’s concept of the Will to Truth, she thought, could reconcile us to the tragedy of existence. Where Shestov saw an unbridgeable gap, Bespaloff made a leap: in the instant, happiness is in our reach. Bespaloff’s ‘happy consciousness’ made a deep impression on Camus who read the book closely in the summer of 1939.

Bespaloff’s writings on Kierkegaard coincided with the publication of Wahl’s Kierkegaardian Studies (1938) – a testimony to their friendship and lifelong collaboration. Bespaloff and Wahl were trendsetters in Paris. Introducing Kierkegaard’s anti-Hegelian philosophy into France, they prepared the ground for the existentialism that flourished in wartime Paris. Their ventures into Christian existentialism directly reacted to Hegel’s revival in France instigated by Alexandre Kojève’s lectures, held between 1933 and 1939. Another émigré from the Russian empire, Kojève was as pivotal as Shestov to the formation of French modernism. It was these refugees from eastern Europe, among them Bespaloff, who shaped the course of French culture by importing new currents to Paris, including Surrealism, Marxism, phenomenology and existentialist philosophy.

In the spring of 1938, Bespaloff began rereading the Iliad with her daughter Naomi. Her extensive notes turned into a brilliant essay on Homer’s epic poem. Shestov’s death that year deeply upset her. In a letter to Wahl, she calls Shestov one of the few truly noble men she knew. The family moved to her husband’s estate in southern France in 1939. Just before the Nazis occupied Paris, she wrote a letter to Marcel: ‘But the worse it gets, the more I realise that you can’t love life, the more I discover the urgent need to find new reasons to love it. And I am afraid that this time I won’t be able to, which would be worse than death…’

Her work on the Iliad essay became an existential ‘method of facing the war’. She soon became aware of a similar text, written coincidentally, that appeared in Cahiers du Sud in 1940: Weil’s ‘The Iliad, or the Poem of Force’. Bespaloff began to revise her essay; she critically responded to Weil’s condemnation of any use of force. Living as a Jew in Vichy France, Bespaloff became increasingly desperate, and with good reason. In November 1941, she wrote to Marcel: ‘I feel as if I am stuck in a sad, restless, absurd dream. And I am very afraid of waking up.’ Her friend Wahl, also Jewish, had been imprisoned and tortured by the Gestapo, and worse was to come for many Jews in Paris.

In 1942, Bespaloff managed to escape, boarding one of last ships to leave Nazi-occupied France, with her mother and daughter, her library and grand piano. Having narrowly fled a concentration camp outside of Paris, Wahl joined them. With his encouragement, Bespaloff began to rework her essay on the Iliad. She eventually finished her notes in yet another exile, this one in New York. Published in English translation in 1943, On the Iliad framed war as an absolute ‘question of losing it all to gain it all’. In the words of Fondane’s letter to his wife, war became ‘the moment to live our existential philosophy’. According to Bespaloff, Homer felt both intense love and intense horror of war. Where Weil claimed that force transforms subjects into objects, Bespaloff, emphasises brief moments of beauty that occur in the midst of violence. With war being waged all around, there are flashing instants of generosity and grace.

In the Iliad, force is both a supreme reality and an illusion. It is the superabundance of life itself, ‘a murderous lightning stroke, in which calculation, chance, and power seem to fuse in a single element to defy man’s fate.’ This does not mean that Bespaloff glorified violence. Far from it. But the experience of the Second World War made her realise the inescapability of force and its power to transform an individual’s understanding of the human predicament. At the heart of her essay is Hector, the ‘resistance-hero’ who embodies justice and courage. Like every human in the Iliad, Hector cannot flee his fate – and he knows it. Hector’s flight from force is short but has ‘the eternity of a nightmare’. That is the horrifying temporality of war that Bespaloff experienced first-hand.

The most crushing parts of Bespaloff’s Iliad essay are dedicated to Helen, a woman with whom she clearly identifies. Clothed in long white veils, she is the most austere character of Homer’s poem. Both unbearably beautiful and unfortunate, Helen awoke in exile and felt ‘nothing but a dull disgust for the shrivelled ecstasy that has outlived their hope.’ She is the prisoner of her own passivity, forced to live in horror of herself. Ultimately, Helen’s promise of freedom, like Bespaloff’s own, remains unfulfilled. Helplessly, Helen watches the men who went to war for her, observing ‘the changing rhythm of the battle’. The breaks that interrupt the fighting are rare instants of silence:

“The battlefield is quiet; a few steps away from each other, the two armies stand face to face awaiting the single combat that will decide the outcome of the war. Here, at the very peak of the Iliad, is one of those pauses, those moments of contemplation, when the spell of Becoming is broken, and the world of action, with all its fury, dips into peace.”

While in New York, Bespaloff preserved her ties to Parisian intellectual life from her exile by exchanging letters with Fessard and Marcel. She got a job with the Voice of America’s French broadcast before moving to Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, where she taught French literature. Mount Holyoke became an important outpost for French culture in the US during the war. At gatherings of exiled scholars organised by Wahl, Bespaloff met Jacques Maritain, André Masson, Marc Chagall and Claude Lévi-Strauss.

This ‘small, dark lady who wore white gloves’, as her translator Mary McCarthy described her, also made an impression on Hannah Arendt who visited in August 1944 to deliver a lecture on Franz Kafka. Arendt’s reading of Kafka, later published in Partisan Review, echoed Bespaloff’s existentialist despair. Under the dark shadow of war, Arendt describes humanity as inescapably trapped in history’s meshes. Kafka’s ‘nightmare of a world’ had become reality. In an essay on Camus, her last published work, Bespaloff describes how history forced her generation ‘to live in a climate of violent death’.

After the war, despite previously having been fêted by them, Bespaloff became a vocal critic of the new generation of French existentialists, especially Sartre. In a 1946 letter to the musicologist Boris de Schloezer, Bespaloff wrote that ‘the hollowness of subjectivity that Sartre opposes to what I call “magical interiority” is much less the foundation of a new humanism than the harbinger of a new conformity.’ She argued that, instead of liberating the individual, Sartre’s existentialism destroyed the magical interiority through which humans can authentically connect with one another. For Bespaloff, Sartre degraded the subject into an object under the gaze of the Other. This objectified ‘subjectivity curiously aligns with American “individualism”, which unleashes itself in action to mask the absence of the individual.’ Like Helen’s Troy, the US felt both dull and hostile to Bespaloff.

Bespaloff’s journey to Mount Holyoke was her final exile. During term break, in April 1949, for reasons not entirely clear, she sealed her kitchen doors and turned on the gas oven. Her own complex fugue ended with a tragic cadence. She had written earlier of the happiness that can be found in an instant. In her final note, alluding to Camus’s claim, she wrote: ‘One can imagine Sisyphus happy, but joy is forever out of his reach.’

Dancing

and time. By Isabel Jacobs, Aeon, December 22, 2023.

'It is

true that our weakness could prevent us from defeating the force that threatens

to overwhelm us. But this does not prevent us from understanding it. Nothing in

the world can stop us from being lucid.'

— Simone Weil

' Humility before the real, before untamable existence, is what we learn from the grief and supplications of the tragic poets and the exhortations and lamentations of the prophets.'

— Rachel Bespaloff

In the

summer of 1939, two women visited an exhibition of Goya’s The Disasters of War

at the Geneva Museum of Art and History. Goya’s 82 etchings, graphic depictions

of the human cost of war, impressed each of them deeply, especially in the

shadow of looming European conflict. The day after the exhibition closed,

Hitler’s troops invaded Poland.

Rachel Bespaloff and Simone Weil did not know each other. They saw the Goyas in Geneva on different days. But they had many things in common. Both were of Jewish descent, and both were French, although Bespaloff had been born in Ukraine. Both were philosophers, consumed by the questions of affliction and human suffering. Both would die too soon—Weil at 34 from malnutrition and heart failure in 1943, and Bespaloff at 53 by suicide in 1949. And both responded to the outbreak of World War II with influential essays on the Iliad.

Homer’s tragic epic, the founding work of European literature, bears impartial witness to the creative and destructive forces at work in the finite historical world. The poet sings of war, but his underlying theme is the complexity of human nature and human experience. There is rage in the Iliad, and cruelty, but wisdom and compassion as well.

With the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the reflections of Weil and Bespaloff on this ancient epic provide a timely lucidity. For example, Weil’s analysis of wrathful Achilles pinpoints the ultimate futility of force. In the Iliad, the harder Achilles tries to enforce his will, the more resistance he generates. Weil could have been describing Vladimir Putin:

“Homer shows us the limits of force in the very apotheosis of the force-hero. Through cruelty force confesses its powerlessness to achieve omnipotence. When Achilles falls upon Lycaon, shouting ‘death to all,’ and makes fun of the child who is pleading with him, he lays bare the eternal resentment felt by the will to power when something gets in the way of its indefinite expansion. We see weakness dawning at the very height of force. Unable to admit that total destruction is impossible, the conqueror can only reply to the mute defiance of his defenseless adversary with an ever-growing violence. Achilles will never get the best of the thing he kills: Lycaon’s youth will rise again, and Priam’s wisdom and Ilion’s beauty.”

Weil argued that the Iliad’s true subject was not any one figure, but the fateful dynamics of force to which both Greeks and Trojans were subject: “Force employed by man, force that enslaves man, force before which man’s flesh shrinks away. In this work, at all times, the human spirit is shown as modified by its relations with force, as swept away, blinded, by the very force it imagined it could handle, as deformed by the weight of the force it submits to.”

In her opening paragraph of her essay, Weil sees both the victors and the vanquished as dehumanized and uncreated by powers not of their own making. The victors are “swept away” when force goes its own way, generating consequences they can’t control. The vanquished are turned into “things,” stripped of the capacity to think, or act, or hope. Even if a victim’s life is spared, he or she is as good as dead. Force “makes a corpse out of [them]. Somebody was here, and the next minute there is nobody here at all.”

Goya’s war images convey this truth. They grant no wider picture of strategy or purpose, but only offer snapshots of an ambient violence, which seems to exist independently of the anonymous actors caught up in war’s depersonalizing horror. “What courage!” reads the artist’s caption, “Que Valor!” Was Goya being ironic? One might interpret this etching as an image of resistance—a brave woman standing on the bodies of her fallen comrades to reach the cannon’s fuse and repel the oppressors. But I can’t help seeing a pile of indistinguishable corpses, and a faceless figure whose own subjection to the laws of force has but one future.

As Weil put it, “for those whose spirits have bent under the yoke of war, the relation between death and the future is different than for other men. For other men death appears as a limit set in advance on the future; for the soldier death is the future, the future his profession assigns him.” [v] In his classic novel of the American Civil War, Stephen Crane said the same thing even more chillingly: War is “like the grinding of an immense and terrible machine.” Its “grim processes” are designed to “produce corpses.”

This pair of photos posted last week by a young Ukrainian couple on social media feels both stirring and sad. Scheduled to be married in May, they realized they might not live that long. So they rushed the wedding. As sirens sounded the Russian attack on Kyiv, they made their vows of lifelong fidelity. Then they took up arms to defend their city. Their courage is inspiring, like the man before the tank in Tiananmen Square. But their vulnerability is heartbreaking. May God protect them.

Weil describes the immutable laws of force, which has no regard for such “perishable joys.” “To the same degree,” Weil says, “though in different fashions, those who use it and those who endure it are turned to stone.” In battle, thought and choice and hope are swept away. “Herein lies the last secret of war,” Weil says, “a secret revealed by the Iliad in its similes, which liken the warriors either to fire, flood, wind, wild beasts, or God knows what blind cause of disaster, or else to frightened animals, trees, water, sand, to anything in nature that is set into motion by the violence of external forces.”

In other words, everyone involved is a victim of war. That is why neither Homer nor Goya seem to take sides. The unflinching visual witness of The Disasters of War may have been undertaken in protest against the brutality of Napoleon’s army in Spain, but as the series evolved it became harder to distinguish the nationality of perpetrators and victims in the images. We only see human beings equally deformed by the workings of force. There is no great cause in these pictures, only suffering.

For me, one of the most disturbing images of the war’s first week was this video of a Russian soldier taking evident pleasure in the firing of missiles into Ukraine. As a Christian, I am obligated to see Christ in his arrogant face, but it is not easy. He is smiling at the death of his fellow beings. The patch on his uniform reads: “They will die and we will go to heaven.” Nevertheless, understanding this man to be himself a victim of force plants a seed of compassion in me. He has lost his humanity to the machinery of war. I must pray for him as well.

In writing about the Iliad, Weil was repeating Goya’s message that “violence obliterates anybody who feels its touch. It comes to seem just as external to its employer as to its victim. And from this springs the idea of a destiny before which executioner and victim stand equally innocent, before which conquered and conqueror are brothers in the same distress. The conquered brings misfortune to the conqueror, and vice versa.

Rachel Bespaloff, writing during the Nazi invasion of France, attributes the Iliad’s impartiality to the seeming impartiality of life itself:

“With Homer there is no marveling or blaming, and no answer is expected. Who is good in the Iliad? Who is bad? Such distinctions do not exist; there are only men suffering, warriors fighting, some winning, some losing. The passion for justice emerges only in mourning for justice, in the dumb avowal of silence. To condemn force, or absolve it, would be to condemn, or absolve, life itself. And life in the Iliad (as in the Bible or in War and Peace) is essentially the thing that does not permit itself to be assessed, or measured, or condemned, or justified, at least not by the living. Any estimate of life must be confined to an awareness of its inexpressibility.”

The impartiality of Homer and Goya is echoed in one of the most remarkable battle scenes in the history of cinema. In Terence Malick’s The Thin Red Line, U.S. marines are trying to take a Japanese position on a Pacific island in World War II. But instead of encouraging the viewer to take sides, the director presents both the Americans and the Japanese as common victims of force, as if we were seeing war through God’s eyes. On the soundtrack the gunfire and explosions remain faint, barely there, while a slow elegiac score, like the music of weeping angels, allows us to reflect on the tragedy of violence instead of stirring our partisan emotions. One of the soldiers, a kind of Christ figure, speaks in voice-over:

“This great evil, where does it come from? How does it still enter the world? What seed, what root did it grow from? Who’s doing this, who’s killing us, robbing us of life and light, mocking us with the sight of what we might have known? Does our ruin benefit the earth? Is this darkness in you too? “

Impartiality is not the same as indifference. Although she favoured pacifism, Weil wrote her essay after joining the fight against fascism in Spain (the near-sighted and clumsy intellectual had to be sent home after accidentally stepping into a pot of boiling oil). She spoke out in favour of struggles for independence in the French colonies, and worked for the French Resistance. Similarly, Bespaloff renounced her own pacifist sympathies when Hitler seized France. Both women felt their ideals constrained by the “yoke of necessity.” Sometimes force simply won’t let you abstain. Bespaloff would later lament that history had forced her entire generation “to live in a climate of violent death,” amid “the smoke of crematories.”

To see everyone as a victim is to realize the limits of force and begin to discover the power of compassion. “Those who live by the sword die by the sword,” said Jesus. And Weil, who got to know Jesus pretty well in her final years, urged us to “learn that there is no refuge from fate, learn not to admire force, not to hate the enemy, nor to scorn the unfortunate.”

This is not a prescription for passivity in the face of naked aggression. Along with most of the world, including many of Russia’s own people, I support the Ukrainian resistance, but it’s not enough just to take sides in the ancient game of force. Even as we are swept up in the necessities of conflict, we must strive to imagine a better way and a better world.

In late 1942, when Weil was working in the London office of the French Resistance, she proposed a plan to parachute hundreds of white-uniformed nurses onto battlefields, not only to tend to the wounded but also to provide an image of self-sacrificial goodness in the midst of cruelty and violence. She herself wanted to be in the first wave of this non-violent invasion. In submitting her plan to the Free French authorities, she made a visionary argument:

“There could be no better symbol of our inspiration than the corps of women suggested here. The mere persistence of a few humane services in the very center of the battle, the climax of inhumanity, would be a signal defiance of the inhumanity which the enemy has chosen for himself and which he compels us also to practice … A small group of women exerting day after day a courage of this kind would be a spectacle so new, so significant, and charged with such obvious meaning, that it would strike the imagination more than any of Hitler’s conceptions have done.”

Charles de Gaulle thought her quite mad, and her plan of course went nowhere. But I always find myself inspired by “impossible” visions which refuse the seductions and delusions of force. When Hitler invaded Poland, W. H. Auden wrote a poem, “September 1, 1939,” calling upon the lovers of justice to “show an affirming flame” in the night of “negation and despair.” As we now weigh our best measures against the worst possibilities, Auden’s key line is more urgent than ever:

“We must love one another or die.”

“We must

love one another or die”—What Does the Iliad Tell Us about the Invasion of

Ukraine? By Jim Friedrich. The Religious Imagineer, March 1, 2022.

Published originally during the Second World War, Simone Weil’s “The Iliad, or the Poem of Force” and Rachel Bespaloff’s “On the Iliad” are two of the last century’s finest discussions of Western literature’s preeminent epic. The former, said Elizabeth Hardwick, “is one of the most moving and original literary essays ever written.” The other, wrote Robert Fitzgerald, “is about the best thing I have ever read on the art of Homer.”1Penned in the author’s native French, the essays were rendered into English by Mary McCarthy. McCarthy’s translation of Weil’s appeared in November 1945, when Dwight McDonald published it in Politics. Its appearance in McDonald’s journal came as no surprise to Bespaloff, who was then negotiating with American editors about a plan to print the two translations together in one volume, a plan unrealized until 2005, when they were finally bound together by the New York Review of Books under the title War and the Iliad.

“On the Iliad” originated in 1938, when its author, a French-Jewish philosopher like Weil, began making notes on Homer’s poem while rereading it with her daughter.As France bore up under the Nazi occupation that ensued two years later, Bespaloff labored to shape her observations into a formal composition, “my method of facing the war,” as she put it. With the help of childhood friend and distinguished editor Jacques Schiffrin, the essay was ultimately published in the United States by Brentano Books upon Bespaloff’s desperate immigration to New York in 1942. The Brentano edition, De l’Iliade, was the basis of McCarthy’s translation, which, in 1947, became the ninth volume of the distinguished Bollingen series.

When, during the winter of 1940, Weil’s “Poem of Force” first appeared as “L’Iliade, ou le poème de la force” in the Cahiers du Sud, it temporarily unnerved Bespaloff, who was then still completing her remarks on Homer’s masterpiece. At a glance Weil’s essay seemed uncomfortably similar to her own. “There are entire pages of my notes that might seem to be plagiarized,” she told Jean Grenier. “What seems clear in retrospect,” says Christopher Benfey in his introduction to War and the Iliad, “is that Bespaloff had written much of her essay while unaware of Simone Weil’s work, but that she made revisions after learning of [what she came to call] the ‘amusing coincidence.’”

It is highly probable, Benfey informs us, that the strange coincidence of the almost simultaneous writing of the two essays is attributable to the influence of Jean Giradoux’s popular drama La guerre de Troie n’aura pas lieu. From the time of its publication in 1935 to Germany’s invasion of Poland, the play was as much in the mind of the French intellectual as the threat of war was in the air of Europe, for its author foredoomed, in comical but no uncertain terms, the inevitable conflict between the Gallic and the German peoples. By the time they came to write on the Iliad, Bespaloff and Weil had internalized Giradoux’s discomfiting themes and dramatized forebodings. The title of one of her early opinion pieces, “Let Us Not Begin Again the Trojan War,” suggests the influence of Giraudoux’s play on Weil’s political imagination. “At the center of the Trojan War, there was at least a woman,” she observed here with reference to the warmongering rhetoric entre deux guerres. “For our contemporaries, words adorned with capital letters play the role of Helen.”

Giraudoux encouraged the French to think of themselves as assailable Trojans, of Hitler and his forces as menacing Greeks at the gates of Troy. The urgency of the play’s message was humorously conveyed by its title, which takes the form of an “official” pronouncement: “The Trojan War will not take place.” In the opening scene, Cassandra begs to disagree. “Doesn’t it ever tire you to . . . prophesy only disasters?” scolds Andromache. “I prophesy nothing,” says Cassandra. “All I ever do is to take account of two great stupidities: the stupidity of men, and the wild stupidity of the elements.” To make Andromache see that war is inevitable, Cassandra asks the queen to “[i]magine a sleeping tiger.” That tiger, she says, has been prodded out of his sleep by “certain cocksure statements,” of which Troy has been “full” for “some considerable time.” After Germany’s invasion of Poland, the ominous parallel between the European crisis and Homer’s epic, which commences with breached pacts and failures to appease the wrath of Achilles, appeared frighteningly apt to Bespaloff and Weil.

While they both acknowledged the “tiger at the gates,” Weil and Bespaloff apparently disagreed on what to do about it. Completed and published before Germany’s defeat of France, the former’s essay condemned war outright and implicitly advocated a pacifist stance toward Hitler. It is significant that McCarthy’s translation was later printed by a Quaker press. Bespaloff’s essay, on the other hand, revised after the occupation, made an implicit case for resistance, and served, whether its author intended it to or not, as a response to Weil’s pacifism. To condemn war, “or to absolve it, would be to condemn life itself,” Bespaloff wrote. “And life in the Iliad (as in the Bible or in War and Peace) is essentially the thing that does not permit itself to be assessed, or measured, or condemned, or justified, at least not by the living.”

Weil and Bespaloff were finally concerned with something more than their own historical moment, however. In the Iliad they sought a significance to history’s entirety, a significance understood only in metaphysical or theological terms and informed by an anthropology grounded in a Judaeo-Christian Hellenism. Their appreciation of Homer’s poem, to find critical accompaniment in American letters, is of the kind intimated in Lionel Trilling’s observation: “When we read how Hector in his farewell to Andromache picks up his infant son and the baby is frightened by the horsehair crest of his father’s helmet and Hector takes it off and laughs and puts it on the ground, or how Priam goes to the tent of Achilles to beg back from the slayer the body of his son, and the old man and the young man, both bereaved and both under the shadow of death, talk about death and fate, nothing can explain the power of such moments over us, or nothing short of a recapitulation of the moral history of the race.”

II

Weil’s is considerably shorter than Bespaloff’s essay, which divides into seven parts, each devoted to a separate topic. Its argument, articulated in the first sentence, consists in this: “The true hero, the true subject, the center of the Iliad is force.”11What it endeavors to show above all else is that in Homer’s poem, and ever in human warfare, souls are utterly transformed by their contact with force, shrunken, mastered, deceived by the force men mistakenly imagine themselves able to handle, misshaped by the force to which men submit involuntarily or otherwise as victims or wielders of it.

Throughout the essay force is understood as that which “turns anybody who is subjected to it into a thing.” To be turned into a thing in the most literal sense, Weil notes, is to be made a corpse. Here stood a man who lies now on the ground, carrion for kites of the sky. There, rattling an empty chariot through the swelling rout, a horse seeks its once splendid driver, whose mangled hulk lies prostrate in a pool of coagulate black, dearer now to ravenous dogs than to his wife. Behind another chariot drags the erstwhile hero, the ensanguined black hair of that once-charming head now hoar with dust. Such is the deadly spectacle of force in Homer’s pageantry of woes, and the “bitterness of such a spectacle is offered us absolutely undiluted,” writes Weil. “No comforting fiction intervenes; no consoling prospect of immortality; and on the hero’s head no washed-out halo of patriotism descends.” Neither Weil nor Homer’s combatants, who fight and perish for ulterior reasons known only to themselves or to the gods, find death in the Iliad sweet or altogether proper.

What Weil deems to be entirely more poignant by contrast than the mere rubbing out of life in the poem is what she calls “the sudden evocation, as quickly rubbed out, of another world: the faraway, precarious, touching world of peace, of the family, the world in which each man counts more than anything else to those about him.” She finds an example of such an evocation in the description of Andromache ordering her serving maids to prepare a hot bath for Hector, soon to return from battle to his palace: “Foolish woman! Already he lay, far from the hot baths, / Slain by grey-eyed Athena, who guided Achilles’ arm.”The tragic sense of these lines derives from one of Weil’s many insights into the human situation: As does nearly all the Iliad, nearly all of human life transpires unfortunately far from the precious joys of home.

Weil contemns most of all the force that “does not kill just yet,” that “merely hangs, poised and ready, over the head of the creature it can kill, at any moment, which is to say at every moment.” Such is the force that turns breathing, thinking men into stones. Countless are Homer’s depictions of this form of force, wherein we see the once proud man, standing disarmed and naked before the pointing spears of his adversaries, become a corpse before any fell hand has touched him. Weil’s commentary on the dehumanizing effects of looming force alludes to these depictions. It also evokes the imagery of notable war poems of her time. What concerned Weil is perfectly represented, for example, in three lines from “The Shield of Achilles,” W. H. Auden’s comment on the spiritual deprivations of World War II: “What their foes liked to do was done, their shame / Was all the worst could wish; they lost their pride / And died as men before their bodies died.”

In her analysis of Homer’s epic and its relevance to the permanent conditions of history, Weil is quick to point out that even those who inflict violence, or stand ready and able to inflict it, suffer the vitiations of force, for it “is as pitiless to the man who possesses it, or thinks he does, as it is to its victims.” Those in the Iliad who think they possess force are intoxicated by a false sense of invincibility, a sense as fleeting as fortune is fickle. For one of the poem’s many incontrovertible truths is that nobody really possesses force. Homer’s world is not divided between conquered persons and suppliants, on the one hand, and conquerors and victors on the other. In it, as in ours, “there is not a single man,” Weil reminds us, “who does not at one time or another have to bow his neck to force.”

Weil invites us to think of Achilles or Agamemnon or Hector or Ajax. More powerful than the common lot of men, none of these combatants wields force absolutely. The Iliad opens with the former weeping in humiliation over Agamem-non’s haughty seizing of Briseis, the woman whom Achilles desired to wed. Even Agamemnon, though, must weep, as necessity requires him to plead humiliatingly with the brooding Myrmidon, whose force he needs to win his war on Troy. Hector, on the other side of the battle line, must suffer the misery of truckling to something latent in himself. To be sure, he strikes mortal fear into the Greek ranks, who stand astonished by his taunting challenges, which they are ashamed to refuse but afraid to accept. When Ajax steps forward, however, Hector feels the irrepressible, embarrassing shudder of terror. Nor is Ajax spared the paralysis of fear, which Zeus causes to overcome the warrior two days later. Though the cause of his own fear is not a man but a river, even dreaded Achilles shakes in his turn as he scurries frightfully up the banks of angry Scamander.

Weil’s essay offers many insights into the Greek mind, and one of the wisest is this: Fate has a way of penalizing those who abuse force while they have it on loan. Such retributive justice operates with “a geometrical rigor” in the Iliad, Weil argues, because it is “the main subject of Greek thought.” She reminds her reader that, in their considerations of the universe and man’s place in it, the idea of retribution (known as Nemesis in Aeschylus’s tragedies) is the starting point for the Pythagoreans, and for Socrates and Plato. The concept is familiar, Weil maintains, wherever the influence of Hellenism has extended, including those countries steeped in Buddhism, where it survives, she speculates, in the concept of Kharma. Weil notes regretfully the absence today of a word in any Western language to express the idea of moral retribution: “[C]onceptions of limit, measure, equilibrium, which ought to determine the conduct of life, are, in the West, restricted to a servile function in the vocabulary of technics.” Of all her reflections on our time, none is truer than this: “We are only geometricians of matter; the Greeks were, first of all, geometricians in their apprenticeship to virtue.”

Weil is finally concerned with the condition of the human soul. When its embodiment is turned into a “thing” by the threat of force, the soul, she remarks, finds itself in “an extraordinary house.” For souls are not created to live in things; those that do are done violence to the quick of their being. Such is the genius of Greek wisdom, of which the “Gospels,” in Weil’s Hellenic view of them, “are the last marvelous expression.” In them, Weil declares, “human suffering is laid bare” in the person of Christ, whose Passion shows that even a divine spirit, incarnate and subjected to material force, “is changed by misfortune, trembles before suffering and death, feels itself, in the depths of its agony, to be cut off from man and God.” In the final analysis, then, Weil’s underlying theme is: In the perpetual struggle against the constraints of the human condition, no embodied spirit long eludes the violence of force, be it human, natural, or supernatural, “although each spirit will bear it differently, in proportion to its own virtue.”

III

Three of the seven sections dividing “On the Iliad” deal with Hector and Achilles. With the former Bespaloff empathizes more than with any of Homer’s other tragic figures. For Hector is the resistance hero, whose happiness consists in family and fatherland. Domestic happiness is for him “more important than anything else, because it coincides with the true meaning of life” and is “worth defending even with life itself, to which it has given a measure, a form, a price.” What causes him to falter in his final hour is not the rancorous valor of Peleus’s insatiably discontented son, but rather Hector’s capacity for happiness. This capacity, says Bespaloff, “which rewards the efforts of fecund civilizations, puts a curb on the defender’s mettle by making him more aware [than Achilles] of the enormity of the sacrifice extracted by the gods of war.”

To Bespaloff’s mind, Hector is nothing if not the quintessential champion of civilization, “the guardian of the perishable joys.” None among the mortals contesting on the windy plains of Troy feels the pangs of loss as deeply as he. To his wife’s desperate plea of nonresistance, he is far from insensible. As he takes his final leave of Andromache and their doomed child, Hector, Bespaloff observes, embraces with a final look what truly matters, exposed as they are to the sullying hands of his enemies. He knows that death, the dreadful premonition of which he cannot shake, means relinquishing all power to protect the ones he loves from humiliation, punishment, torture.

To deny fate, though, is to deny his place among the subjects of the epic poet who, in ages hence, will resurrect Ilion and immortalize its champions. So Hector steps up to Achilles, who pursues him “not around the walls of Troy but in the cosmic womb itself,” as Bespaloff recollects their struggle sub specie aeternitatis. Humiliated though he is, Hector finally conquers himself (the only thing left him in the end), defies destiny, and steels himself for a glorious failure. This is no insignificant feat, Weil would have us note, for in the minds of Homer’s warriors, “glory is not some vain illusion or empty boast; it is the same thing that Christians saw in the Redemption, a promise of immortality outside and beyond history, in the supreme detachment of poetry.”

In Hector’s destroyer Bespaloff sees the uncivilized man whose capacity for happiness remains undeveloped because his “appetite for happiness” has not been fully satisfied and drives him “on toward his prey and fills his heart with ‘an infinite power for battle and truceless war.’”Even though in his forcefulness Achilles is enviably half-divine, his dual nature adds to his discontent, his divinity and humanity being violently inharmonious: “As a god, he envies the gods their omnipotence and immortality; as a man, he envies the beasts their ferocity, and says he would like to tear his victims’ bodies to pieces and eat them raw.”

Insofar as his life is brutish and short, Achilles, according to Bespaloff’s characterization, resembles Hobbes’s primitive man. Or perhaps he is more comparable to Rousseau’s noble savage. In any case, he defies every earthly or deific authority and scoffs at being supplicated in the name of anything high or low. He has, as Conrad describes Kurtz, “kicked himself loose of the earth,” has “kicked the very earth to pieces.” When dying Hector begs him not to feed his remains to the dogs, Achilles is obdurate and, as Bespaloff points out by way of Achilles’s own insensitive words, quite aware of being something other than a civilized man: “There are no covenants between men and lions. . . . It is not permitted that we should love each other, you and I.” Yielding at once to truth and death, Hector recognizes his mistake: “Yes, I see what you are. . . . A heart of iron is in you for sure.”

More chief than king to his Myrmidons, Achilles “spends himself without reckoning, in a rapture of aggressiveness.” Through him, says Bespaloff, Homer reveals the limits and the futility of force, which, in its acts of cruelty, avows at once its desire and inability to achieve godhead. She explains: “When Achilles falls upon Lyacon, shouting ‘death to all,’ and makes fun of a child who is pleading with him, he lays bare the eternal resentment felt by the will to power when something gets in the way of its indefinite expansion.” In Achilles Bespaloff sees weakness manifesting itself in the very consummation of force, because Achilles, the consummate force-hero, “can never get the best of the thing he kills: Lyacon’s youth will rise again and Priam’s wisdom and Ilion’s beauty.”

Bespaloff abstains from simplifying Achilles. At once an image of grandeur and a marvelous ingrate, he is, according to her discerning assessment, many things still: “The sport of war, the joys of pillage, the luxury of rage, ‘when it swells in a human breast, sweeter than honey on a human tongue,’ the glitter of empty triumphs, and mad enterprises—all these things are Achilles.” Men need him, as they need death, for both place formative and necessary limits on life. “Without Achilles, men would have peace,” we read in Bespaloff’s meditation on Homer’s foremost enigma. Without him, “they would sleep on, frozen with boredom, till the planet itself grew cold.”

Foe to every impulse of pity though he is, this lord of limit remains the son of Thetis, whom filial love for a mortal has made to feel the pangs of human suffering and to regret her immortality. From this maternal goddess of “the fair tresses,” Achilles, writes Bespaloff, “inherits a grace even in the midst of violence, a generosity that is quick and unpremeditated.”A leaden heart is in him, to be sure. But, owing to Thetis and her exalting influence, it is not entirely immovable and finally proves to be a noble heart when Priam, the noblest of suppliants, moves it with his winning plea for mercy: “I am far more pitiable [than your own father], for I have endured what no other mortal on earth has, to put to my mouth the hand of a man who has killed my sons.”

Hector and Achilles embody the respective psychologies of their constituents. Regardless of what happens, the Achaians, like the latter, remain convinced of their invincibility. The Trojan princes contradistinctively share Hector’s premonition of defeat, even when the tide of battle turns in their favor. Bespaloff meditates at length on Hector and Achilles because for her the duel between them, not Achilles’s wrath nor his dispute with Agamemnon over Briseis, constitutes the epic’s center, its unifying principle.

IV

The balance of “On the Iliad” is chiefly concerned with the gods in relation to Homer’s major figures and with Homer in relation to Tolstoy. While the epic hero assumes responsibility for all that happens, the gods, according to Bespaloff’s assessment of their morality, assume responsibility for nothing, though all that happens has been wrought by them. But from his forceful struggle against the god’s irresponsibility the epic hero gains his dignity, as does Hector in the final moments of his death. Helen, too, gains what dignity she has from her struggle against the fatuous gods, inasmuch as she achieves a measure of nobility in her splendid disgrace.

Nietzsche was wrong, Bespaloff declares, when he called Homer the poet of apotheosis: “What [his epic] exalts and sanctifies is not the triumph of victorious force but man’s energy in misfortune, the dead warrior’s beauty, the glory of the sanctified hero, the song of the poet in times to come—whatever defies fatality and rises superior to it, even in defeat.” While acknowledging the mortal struggle against material force in the Iliad, she maintains that Homer’s is an interest primarily in the “limited and finite aspect [of force] as perishable energy that culminates in courage.”Homer’s eternity, she reminds her contemporaries, centers round the striving wills of individuals and exists in the exalted tale of extraordinary deeds: “Homer asks no quarter, save from poetry, which repossesses beauty from death and wrests from it the secret of justice that history cannot fathom.” Against the comedy of the gods and the contingencies of fate “is set,” in Bespal-off’s words, “the creative lucidity of the poet fashioning for future generations heroes more godlike than the gods, and more human than men.”

While irresponsible and actually less godlike than the epic hero, the gods are not without their significances. Bespaloff notes, in particular, the shared significance of Hera, seemingly witless though able to manipulate the father of the gods; Aphrodite, whimsical yet not as defenseless as she appears; and Pallas Athena, brooding but quick to send haughty Ares reeling to the ground with a single blow: “These are the three goddesses involved in the judgment of Paris, and each in her own way reveals the other side of the eternal feminine whose tragic purity is embodied in Andromache, Helen, and Thetis.” And there is Zeus, of course: Mere watcher though he is, his “serene look, dominating from on high consequences still distant, prevents the Trojan War from being a mere bloody fracas” and “conveys to the flux of events its metaphysical meaning.”

In the final analysis, however, Zeus’s court is to the Iliad what worldly society is to War and Peace. Both, says Bespaloff, are targets of ridicule. Homer’s deities and Tolstoy’s worldlings, beings exempted by fortune from the fate of ordinary men, exhibit something of a decorative showiness that carries neither force nor weight. The gods of the epic and the aristocrats of the novel are both exquisitely comic in their interaction with one another and careless of the mortals whom they use for their sport. They lack a certain seriousness, Bespaloff observes, which for Homer and Tolstoy distinguishes the truly human from the subhuman. “Agents provocateurs, smart propagandists, heated partisans, these non-belligerents do not mind the smell of carnage or the clash of tragic passions,” she writes. In truth, they rely upon it: “Condemned to a permanent security, they would die of boredom without the intrigues of war.”

Nor would old mortality be quite the same, from the point of view of Homer and Tolstoy, without war to make peace meaningful. Thus it is futile, Bespaloff insists, to look to them for a condemnation of war as such. Neither pacifist nor bellicist, both love and fear it, have no misconceptions about it, and “present it as it really is, in its continual oscillation between boisterous animal spirits that break out in spurts of aggressiveness and the detachment of sacrifice in which the return to the One is consummated.” For Homer and Tolstoy war, according to Bespaloff, is one of the ineluctable conditions of life; it is to be regretted, certainly, perchance remembered in verse, but not to be judged any more than destiny.

In their art, war becomes something of a relative good when viewed, as they view it, under the aspect of eternity. Bespaloff understands this way of seeing the inevitable: “Precisely because war takes everything away from us, the All, whose reality is suddenly forced on us by the tragic vulnerability of our particular existences, becomes inestimable.” Nor is man’s love of country, rooted as it is in his passion for eternity, as fully palpable as when it is tested by war: “Faced with this ultimate threat man understands that his attachment to the country which willingly, or unwillingly, he has made the center of his world, the dwelling place of his gods, and his reason for life or death, is no pious and comfortable feeling, but a grim demand imposed upon his whole being.” The threat of slavery or of annihilation denudes—but it also exalts. As Bespaloff remarks: “Pierre [Bezhukhov], [Prince] Andrey, Hector, and Achilles are never more themselves than when they are on the verge of being nothing.”

Bespaloff draws a striking parallel between the Ionian poet and the demiurge of Yasnaya Polyana. Her essential claim is that their world is what ours is in perpetuity: We do not enter it, for we are always there. Homer and Tolstoy along with Shakespeare are, she declares, “the only ones . . . who are capable of those planetary pauses, those musical rests, over an event where history appears in its perpetual flight beyond human ends, in its creative incompleteness.” In her final assessment of their comparability, however, Bespaloff argues that Homer far exceeds Tolstoy. The Greek, she explains, who insists that Achilles and Priam exchange mutual homage, never betrays a preference for his own people; his paradigm of human virtue is, after all, Hector, a Trojan. The Russian, on the other hand, cannot resist decrying and belittling the French, and for him “reciprocal esteem becomes impossible” because he sees Napoleon as “not only the invader of his country, but also God’s rival.”

V

One can fully appreciate the essays revisited here only by experiencing them for himself. For they are neither reducible to any terms short of those which translate the originals into English nor satisfactorily expressible in any summary or paraphrase. What impels their description here is the hope that they will find readers in our day. If their present appreciator had his way, both would be required reading for all university English majors, for the authors exemplify the art of enduring literary criticism penned “in the light of eternity,” to borrow a phrase from Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Each defies the New Historicist imperative to view works of the moral imagination as mere products of their time, an imperative which literary theorists and literature professors alike have abided dogmatically ever since Marxist ideologue Fredrick Jameson gave the command: “Always historicize!”

Weil and Bespaloff were certainly aware that one derives a fuller understanding of its moral significance from historical interpretation of a literary work. But, unlike today’s typical critic of the New Historicist persuasion, their aim was to rise above the mere historicity of literature to see the eternal significance of its conceits and symbols. For them the greatest of poems, the Iliad, was nothing if not an explanation of the universal relevance of their ravaged century. The epic’s encarnalizations of truth were for both writers insights into the very depths of being. Homer was for Weil and Bespaloff a celebrant of the imagination who turned the world into words through which posterity could enter from time to time into the realm of permanence, “charioted on the viewless wings of poesy.”

There is no denying that Weil and Bespaloff are guilty of “killing time,” to appropriate the phraseology of one New Historicist. Note, for instance, the tenor of this passage from the former’s opening paragraph: “For those dreamers who considered that force, thanks to progress, would soon be a thing of the past, the Iliad could appear as an historical document; for others, whose powers of recognition are more acute and who perceive force, today as yesterday, at the very center of human history, the Iliad is the purest and loveliest of mirrors.” Yes, Weil’s criticism is chronologically homicidal, insofar as it rejects the fundamental tenets of the New Historicism and sees history in the light of that which moves but moves not.

Like Weil, Bespaloff turned to the “purest and loveliest of mirrors” because in it she saw embodied immutable truths about man’s predicament. Of special interest for her was Helen, Homer’s embodiment of human error. In literature, if not in life itself, Helen is a tragic type we see time and again; she is akin to Anna Karenina, for instance, with whom Bespaloff compares her at length. Politically, and according to Bespaloff’s final comment on the mythical cause of the Trojan War, Helen is always with us “since nations that brave each other for markets, for raw materials, rich lands, and their treasures, are fighting first and forever, for Helen.” Is Bespaloff altogether wrong? Does not every war, just or unjust, have its Helen, its La Belle Dame Sans Merci? Is not Helen, in one rhetorical form or another, what Conrad means by the “idea” that redeems “the conquest of the earth,” the “unselfish belief in the idea,” the beautiful lie men continually “set up, and bow down before, and offer a sacrifice to”?

In her discussion of Helen, Bespaloff reminds us that in Homer’s mind punishment and expiation do not fix responsibility for error: “They dissolve it in the vast sea of human suffering and the diffuse guilt of the life-process itself.”To be sure, the Greek notion of universal defectiveness bears some relation to the Christian idea of Original Sin. For back of Attic tragedy, epic or dramatic, is always the idea of a fall. But, as Bespaloff is quick to point out, a fall in the Homeric sense is not preceded by a state of innocence and does not anticipate redemption in any Christian sense. It is true that Homer sees the universe as inherently flawed. But in a flawed universe in which salvific grace and redemptive remorse are meaningless phrases, individual error, she explains, “is not quite the same thing as a sin.”

To speak of correspondences between the Greek, Jewish, and Christian visions of order is to come finally to the nexus of Weil’s and Bespaloff’s thought. To clarify this connection of minds, it may be said that, for both Weil and Bespaloff, Jehovah’s justice supersedes Homer’s force, as Christ’s love supplants Jehovah’s justice. To these correspondences Bespaloff was keenly sensitive, and, according to Hermann Broch, to reveal them “seems to have been [her] purpose in linking the Homeric epic with biblical prophecy.”Such was Weil’s purpose, too.

In fact, appeals to these correspondences are present not only in “Poem of Force,” but also in many of the letters and commentaries Weil wrote prior to and in the wake of the essay’s publication and translation. Several of these remarks chime perfectly with what one critic has called the “numinous and redemptive” pedagogical function of Bespaloff’s essay, which “superbly mediates the relations between literature and religion.”For instance: “It is impossible to love at the same time both the victors and the vanquished, as the Iliad does, except from the place, outside the world, where God’s Wisdom dwells.”These words, quoted from Weil’s “Contemplation of the Divine,” are predicated on a belief in the reconcilability of the Greek and Christian worlds, a belief which Weil shared with her compatriot.

That Weil took this reconcilability seriously is further exemplified in her last and lengthy letter to Father Perrin. Here she discloses in Homer one of her main themes (a theme which Bespaloff’s essay advances in its concluding paragraphs): In the afflicted soul shines brightest “the splendour of God’s mercy.”Knowledge of God’s presence, Weil reminds Perrin, affords no “consolation,” removes “nothing from the fearful bitterness of affliction,” leaves unhealed “the mutilation of the soul.” Yet, as she goes on to relate in terms evoking at once the Incarnation and the Passion, “we know quite certainly that God’s love for us is the very substance of this bitterness and this mutilation.” Nothing surpasses the Iliad, Weil tells Perrin, in its capacity to bear witness to this certainty. Indeed, its witness to this certainty is, she maintains, “the implicit signification of the poem and the one source of its beauty,” notwithstanding the fact that this signification “has been scarcely understood.”

Antithetical to the discourse of New Historicism, Weil’s words illustrate what Bespaloff says in her essay’s final summarizing sentence: “[T]here is and will continue to be a certain way of telling the truth, proclaiming the just, of seeking God and honoring man, that was first taught us and is taught us afresh every day by the Bible and by Homer.” In other words: the way to truth is through the wisdom of the Logos as we find it inscribed in great poems and incarnate in the figures of the ethical poet. “If the religion of the Bible and the religion of Fatum both resort to poetry in order to communicate with the people,” writes Bespaloff, “this is because poetry gives them back the truth of the ethical experience on which they are based.”Only on the language of poetry, on “aphorism and paradox,” is Nietzsche able to proclaim “his Dionysiac faith in the Eternal recurrence,” Blake to describe “his vision,” Kierkegaard “to puzzle out Abraham’s experience,” Pascal “to acknowledge the God of Abraham and Jacob.” In their parts and in their wholes the essays remembered here affirm this epistemological verity.

Reading the Iliad in The Light of Eternity. By Cicero Bruce.. Intercollegiate Studies Institute, October 8, 2014.

HECTOR- In Baspaloff’s essay, “the true center” of the epic poem is the tragic confrontation of the revenge-hero and the resistance-hero. Achilles and Hector respectively. And the confrontation is a constantly changing rhythm, making everything uncertain. In the Iliad, the distinctions between good and bad do not exist.

there are only men suffering, warriors fighting, some winning, some losing.

Bespaloff seems to diverge from the argument on force made by Simone Weil.

To condemn force, or absolve it, would be to condemn, or absolve, life itself.

And life in the Iliad...is essentially the thing that does not permit itself to be assessed, or measured, or condemned, or justified, at least not by the living. Any estimate of life must be confined to an awareness of its inexpressibility.

Life unfolds in all its inevitability and the stage play of life shines a light on the core of man’s existence. It’s this dance, sometimes macabre, sometimes sublime that is the Cosmos. History is blind to all this, but the poet can set heroes before us godlier than the gods and more human than men.

THETIS AND ACHILLES- The bond between Thetis and Achilles comprises some of the tenderest scenes in the Iliad. Thetis, one of the gods, exhibits in her relationship with her son Achilles all of the human, mortal emotions of a mother. Achilles’ ardent attachment to his mother contrasts sharply with Hector’s relationship with his mother, Hecuba. Achilles is anchored to humanity by the tenderness he feels for his mother. This saves him from dissolving into myth.

HELEN- There really wasn’t much focus on Helen, either in the Iliad or in Logue’s rendering. But Bespaloff starts right off with Of all the figures in the poem, she is the severest, the most austere. She uses words and phrases like penitent and royal recluse. She has lost her freedom – not directly through the actions of Paris or Menelaus – but by the will of the gods – especially Aphrodite, who plays her like a ukulele And is there hope for freedom under that immortal bondage? Either outcome of the war will still not set her free. Bespaloff is particularly cogent here, and passionate. An exile herself, this is very telling:

Homer is as implacable toward Helen as Tolstoy is toward Anna. Both women have run away from home thinking that they could abolish the past and capture the future in some un- changing essence of love. They awake in exile and feel nothing but a dull disgust for the shrivelled ecstasy that has outlived their hope.

Having not yet appeared in human history, Homer likens Helen’s guilt to original sin – before redemption and grace were an option. Before the specific “fall” of original sin, there was no state of innocence, only the absurdity of existence and the downward and inevitable spiral to mortal death. Unlike the-gods-made-me-do-it Paris, Helen doesn’t comfort herself with the gods culpability, but accepts the tragic guilt herself. As Helen realizes the moral weakness of Paris, she is more and more humiliated by his presence. She is alone and outcast behind the walls of Troy then – except for Hector. Without evincing a hint of lust, Hector shows Helen a good deal of compassion. Interestingly, according to Bespaloff, Homer represents beauty (in the guise of Helen) not as a gift, but as a curse. Then Baspaloff likens it to force or fate, which is the whole point of bringing the concept of beauty up

Like force, it subjugates and destroys – exalts and releases.

Homer never particularly details the beauty of Helen, of Thetis, of Andromache. But we intuit their beauty, they are recognizable to us, the modern reader. By the reaction of others to their presence they are known. People stop and stare and her beauty frightens them like a bad omen, a warning of death. Priam however, does not blame her, but blames the gods. Helen loses herself for a moment in reverie [from the Iliad]

“There was a world…or was it all a dream?”

When Eve was blamed for the original sin, it was her beauty that initiated man’s fall. Was the Garden of Eden like a dream as well? Beauty takes a hit again from the gods. Not from Baspaloff, or from Homer:

The curse which turns beauty into destructive fatality does not originate in the human heart. The diffuse guilt of Becoming pools into a single sin, the one sin condemned and explicitly stigmatized by Homer, the happy carelessness of the Immortals.

THE COMEDY OF THE GODS- While the gods lay about in their stand-up (or in this case chaise-lounging comic style), they take no responsibility for anything they have caused. These are not good ‘parents’ where responsibility begins at home. Their mortal playthings meanwhile take all sorts of blame upon themselves, even when as is all too obvious it was out of their hands. It’s ironic, is it not, that taking responsibility for your actions is a lesson that man (back then anyway) took to heart. Not the gods, though. If in the present, God has died (or left us to our own devices) have they (He) left us this trait for not accepting responsibility for our actions as well?

Without the sins of the lust for power, war, betrayals, the gods would plain be bored to death. Even the God Apollo hates this about their divinity.

Bespaloff likens the relationship between Hera and Zeus, the tricks she plays on him and their give and take bartering, to musical comedy. There’s Aphrodite as well, all batting eyes and innocence – but she knows what she’s doing. And Athena, a warrior with a man’s muscles. These three gods (Hera, Aphrodite and Athena) were the three that got the ball rolling: at The Judgement of Paris.

Zeus even laughs pleasurably after he has unleashed the gods to intervene to their heart’s content. It’s all great sport. Unlike the god of Ismael, Zeus does not intervene directly, though he has his preferences. He distributes and watches. From Homer

There are two great jars that stand on the floor of Zeus’s halls

and hold his gifts, our miseries one, the other blessings.

When Zeus who loves the lightning mixes gifts for a man,

now he meets with good fortune, now good times in turn.

When Zeus dispenses gifts from the jar of sorrows only,

he makes a man an outcast – brutal, ravenous hunger

drives him down the face of the shining earth,

stalking far and wide, cursed by gods and men.

God is the distributor. Man is the receiver and he has to deal.

TROY AND MOSCOW- This is really a short comparison of two epics: Homer’s of course and Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Not much of interest here (for me at least) although it’s certainly possible that much of it went over my head! Can you believe it!! [insert ironic icon]. Except this: Bespaloff points out that Homer treats the forces of Troy and the Greeks equally (even though he is a Greek). Not so Tolstoy. There is no such impartiality for the enemies of Mother Russia. Impartiality does not obviate harshness, or vengeance – or magnanimity, for that matter. Here Bespaloff differentiates between “force” and “spirit”.

When war is seen as the materialization of a duel between truth and error, reciprocal esteem becomes impossible. There can be no intermission in a contest that pits – as in the Bible – gods against false gods, the Eternal against the idol. This is a total war, which must be prosecuted on all grounds and in all weathers, till the extermination of the idol and the extirpation of the lie are accomplished.

This is a scary thought and is another way of seeing the message of the ‘true-believers’.

PRIAM AND ACHILLES BREAK BREAD- For Bespaloff, when Priam kneels down to the man who murdered his sons, there is nothing demeaning about the gesture. It has the ring of truth. This is “the only case in the Iliad where supplication sobers the man to whom it is addressed instead of exasperating him”. This is where Achilles has the great epiphany. He’s as much a victim of force as Priam (this hearkens back to Weill). He becomes a man again, casting off (at least temporarily) his mantle of doomed tragic-war hero.

POETS AND PROPHETS- In this, the last section of Bespaloff’s essay On The Iliad, she takes a step back – or in the current vernacular flies up to 30,000 feet For her, between the Bible and the Iliad our experiences are encompassed in – some times in rich truth and sometimes in contradiction.

They offer us what we most thirst for, the contact of truth in the midst of our struggles.

She argues for the “profound identity” between these two bodies of thought. Despite the contradictions, don’t over analyze one or the other she advises. They have more in common than we might expect. She makes a good argument.

War and The Iliad - Rachel Bespaloff on The Iliad. . By Chazz W. ChazzW Wordpress January 5, 2012.

La Guerre de Troie n'aura pas lieu. 1935

The critic Kenneth Burke once suggested that literary works could serve as “equipment for living,” by revealing familiar narrative patterns that would make sense of new and chaotic situations. If so, it should not surprise us that European readers in times of war should look to their first poem for guidance. As early as the fall of 1935, Jean Giraudoux’s popular play La guerre de Troie n’aura pas lieu encouraged his French audience to think of their country as vulnerable Troy while an armed and menacing Hitler was the “Tiger at the Gates” (the play’s English title). Truth was the first casualty of war, Giraudoux warned. “Everyone, when there’s war in the air,” his Andromache says, “learns to live in a new element: falsehood.”

Giraudoux’s suggestion that the Trojan War was an absurd contest over empty abstractions such as honor, courage, and heroism had a sinister real-life sequel when Giraudoux was named minister of wartime propaganda in 1939. In the wake of Munich, Minister Giraudoux announced that the most pressing danger to French security was not the Nazis but “one hundred thousand Ashkenasis, escaped from the ghettos of Poland or Rumania.”

After September 1939, the analogy between the crisis in Europe and the Iliad—which opens with broken truces and failed attempts to appease Achilles’ wrath—seemed altogether too apt. During the early months of the war, two young French writers of Jewish background, Simone Weil and Rachel Bespaloff, apparently unaware of the coincidence, wrote arresting responses to the Iliad that are still fresh today. During the winter of 1940, Weil published in the Marseilles-based journal Cahiers du Sud her famous essay “L’Iliade, ou le poème de la force.” Three years later—after both Weil and Bespaloff had fled France for New York—Jacques Schiffrin, a childhood friend of Bespaloff’s who had become a distinguished publisher, published De l’Iliade in New York under the Brentano’s imprint.

The idea of bringing these two complementary essays together was first pursued by Schiffrin and Bollingen editor John Barrett. After Mary McCarthy translated both essays into English plans were made to publish them in a single volume. When rights to Weil’s essay proved unavailable, Bespaloff’s On the Iliad appeared separately in 1947, as the ninth volume in the Bollingen series, with a long introduction—nearly half as long as Bespaloff’s own essay—by the Austrian novelist Hermann Broch, author of The Death of Virgil. In their respective essays, Weil and Bespaloff adopt some of the same themes while diverging sharply in their approach and interpretation. In her essay Weil condemns force outright while Bespaloff argues for resistance in defense of life’s “perishable joys.”

1.

Most of human life, Simone Weil wrote in her essay on the Iliad, “takes place far from hot baths,” but her own discomforts were mainly self-inflicted. She was born in Paris in 1909 into an assimilated, well-to-do Jewish family. Her father was a kindly internist and her mother a forceful woman who looked after the children. Simone Weil was a gifted child, graduating first in her class in philosophy—Simone de Beauvoir was second—at the École Normale Supérieure in 1931. Her mentor was the philosopher Émile Chartier, known as “Alain,” under whose guidance Weil’s political convictions began to surface. Beauvoir recounts her first—and last—conversation with Simone Weil:

“She intrigued me because of her great reputation for intelligence and her bizarre outfits…. I don’t know how the conversation got started. She said in piercing tones that only one thing mattered these days: the revolution that would feed all the starving people on the earth. I retorted, no less adamantly, that the problem was not to make men happy, but to help them find a meaning in their existence. She glared at me and said, “It’s clear you’ve never gone hungry.” Our relations ended right there.”

Simone Weil had never gone hungry either, but during the mid-1930s she began to seek opportunities to experience the suffering of others. During 1934–1935 she took a break from her teaching to work on the assembly line at a Renault factory. Two years later she was in Spain, enlisting in a workers’ brigade against Franco’s forces. The physical frailty and clumsiness that had made factory work such a trial for her brought near disaster when she stepped into a pot of boiling oil and severely burned herself, forcing her to return to the world of bourgeois safety she so despised.

Weil’s experiences in the Renault factory and in Spain confirmed her growing convictions regarding the dehumanizing effects of modern industrialism and war. She traced these tendencies back to the ancient Romans who, in her view, established a mechanistic regime based on brute force. In several powerful essays written during the mid-1930s, she lamented the Romans and argued that Napoleon and Hitler were their imperial successors.

A committed pacifist, Weil argued for negotiations with Hitler and endorsed Neville Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement. Alluding to Giraudoux’s caustic play, she wrote an essay, published in 1937, titled “Let Us Not Begin Again the Trojan War,” in which she condemned the debasement of civic language. “At the center of the Trojan War, there was at least a woman,” she wrote. “For our contemporaries, words adorned with capital letters play the role of Helen.”