A

19th-century painting of a murderess concocting a poison to kill her husband’s

lover has been acquired by a Los Angeles-based nonprofit that hopes to unravel

its secrets. The Arts of Imagination Foundation, an organization dedicated to

the preservation of culturally significant archetypal narrative artwork,

purchased British portrait artist John Collier’s oil on canvas work “The

Laboratory” (1895) via a Christie’s private sale for an undisclosed price.

A

successful portraitist in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Collier

painted in a Pre-Raphaelite style and was especially drawn to illustrating

scenes circulating around mysterious social narratives that encouraged

speculation and fueled debate amongst audiences. Known as “problem pictures,”

the paintings focused on characters caught in moral dilemmas that incited

gossip amongst curious viewers as though they were real scenes. Notable

examples of these works by Collier included “The Prodigal Daughter” (1903) and

“A Fallen Idol” (1913), which both feature women caught in incomprehensible

predicaments that inspired viewers to imagine possible explanations behind the

perplexing scenes.

“These

kinds of paintings were major draws at the annual Royal Academy summer

exhibitions, designed to be sold, certainly, but also to attract popular and

press attention,” art historian Pamela Fletcher told Hyperallergic. A professor

of art history at Bowdoin College, Fletcher penned an essay about “The Prodigal

Daughter” for the Royal Academy Chronicle.

“In the

1890s, Collier painted a number of fairly dramatic subject pictures drawn from

history or literature — ‘The Laboratory’ fits into this category, which also

includes scenes of Clytemnestra, Cleopatra, the Borgias, and others,” she

added.

In “The

Laboratory,” Collier illustrates a scene in which a woman and an apothecary

prepare a fatal elixir for her husband’s lover. The painting is based on Robert

Browning’s 1844 poem of the same name, which centers on the true story of

French aristocrat Marie-Madeleine d’Aubray, Marquise de Brinvilliers, who was

executed in 1676 for poisoning her father and two brothers and attempting to

murder her husband. When “The Laboratory” was first unveiled in 1895, it stood

out for its purposeful ambiguity, scandalous undertones, and Collier’s dramatic

use of light, which he often employed as a device to intensify a scene’s moral

enigma and suspense.

The Arts of

Imagination Foundation was founded by writer and director Brady Schwind, who

began tracking down the artwork behind Frank L. Baum’s Oz book series as part

of his Lost Art of Oz initiative. The organization purchased the piece to

commemorate the Gothic literary movement of Britain’s late Victorian period.

“As a

theatre artist and storyteller, I have long understood that stories bring us

together,” Schwind told Hyperallergic in a statement, explaining that he

launched the nonprofit last year to commemorate archetypal stories and the art

inspired by them. The nonprofit has created a virtual portal for viewers to

learn more about “The Laboratory” and its backstory, as well as Collier and his

work.

“Scholars

have sometimes attributed the late 19th-century interest in such scenes of the

‘femme fatale’ to a reaction against the increasingly visible and powerful

feminist movement of the period, as women activists worked to secure the vote

and other forms of social and political equality,” Fletcher said.

But Collier’s paintings, she continued, “showed modern women in ambiguous narrative situations (often around issues of sexuality), inviting viewers to draw their own conclusions about the women’s motives, histories and moral choices.”

The

Painting of a Murderess That Scandalized Victorian Audiences. By Maya Pontone.

Hyperallergic, September 25, 2023.

“It is a

melancholy fact that more nonsense can be talked about art than about any other

subject, and writers of treatises on painting, from the great Leonardo

downwards, have not been slow to avail themselves of this privilege.”

John

Collier

John

Collier was a British artist and writer who is known for his paintings and

illustrations that explored social issues. His works often sought to explore

the human condition and the plight of the working class. Many of his paintings

feature themes of poverty, injustice, and exploitation. He often depicted the

struggles of the poor and working-class people in England during the late 19th

and early 20th centuries. Collier’s work was heavily influenced by the social

realism movement and sought to raise awareness of the hardships faced by the

working class. He was also a member of the Socialist movement and believed that

art had the power to bring about social change. His works often employed a

vivid colour palette and a focus on detail that sought to bring a sense of

realism to the subjects he chose to paint.

John Maler

Collier was born on January 27, 1850 in London, United Kingdom. John studied at

Eton College and Slade School of Fine Art. Also, in 1875, he attended the

Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. During his time in Paris, Collier studied art

under Jean-Paul Laurens. Collier’s exploration of social issues in his art was

varied and multifaceted. He was particularly interested in exploring the

problems of poverty and inequality, and he often juxtaposed the rich and the

poor in his paintings. His works often featured the plight of the working class

and the harsh conditions they often endured. He also sought to portray the

plight of those in power and their abuse of their position.

Collier

often depicted the working class in a sympathetic light, emphasizing the

hardships they faced in their daily lives. He sought to highlight the struggles

of this often-overlooked segment of society, and to bring attention to their

plight. In his paintings, Collier often depicted the poor in dignified and

heroic poses, emphasizing their humanity and strength in the face of adversity.

In his painting, “The Last Muster,” he shows a group of elderly soldiers

gathering for a final muster before disbanding. This painting serves as a

commentary on the plight of veterans and the lack of recognition they often

receive from society.

Brotherhood of Man

Collier

also used his art to address issues of poverty and inequality. His painting, “A

Peep into the Future,” depicts a family of four living in a cramped tenement

room. The painting conveys the struggles of living in cramped and unhealthy

living conditions, and the poverty that many working-class families faced

during the era.

Collier

also explored the changing nature of gender roles in his work. He often

depicted women in positions of power and authority, challenging traditional

stereotypes of women as passive and subservient. Collier also used his art to

criticize class divisions, highlighting the gap between the wealthy and the

poor. In his painting “The Cries of London,” Collier highlights the plight of

women in Victorian society. The painting features a group of women selling

their wares in the street, and serves as a commentary on the limited

opportunities available to women during the era.

In addition

to his artwork, Collier also wrote a number of books that explored social

issues. His most famous work, The Woman Who Did, explored the controversial

issue of free love and the role of women in society. His writing was often provocative,

and he used it to bring attention to important social issues of the time.

Collier’s

work was also highly critical of organized religion, particularly in regards to

its influence on the working class. He was a strong advocate for secularism and

often portrayed the hypocrisy of religious institutions. He also sought to

explore the hypocrisy of the upper classes, and often drew attention to their

lack of concern for the less fortunate.

John

Collier’s exploration of social issues in his art was varied and multifaceted.

His works sought to explore a wide range of issues, from poverty and inequality

to the hypocrisy of the upper classes and organized religion. His work was

highly influential in the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and his vivid use of color and

attention to detail made his works particularly striking and memorable.

Collier’s works continue to resonate with viewers today, and serve as an

important reminder of the social issues that still persist in our society.

John

Collier’s Exploration of Social Issues in his Art. By Abhishek Kumar. Abir Pothi, January 27, 2023.

Britain is

not a country known for its great painters. In fact, I challenge my readers

outside the UK to name one. J. M. W. Turner or John Constable are the likely

choices for most people and that’s a fair claim. Both men are brilliant artists

and Turner’s work especially comes alive when you stand before it. However,

neither man is a patch on John Collier, one of my favourite painters, and I’m

going to spend the next few minutes convincing you of his greatness.

Life

Art

aficionados will have heard the name John Collier. How could they not

considering his extensive catalogue from the late-Victorian and Edwardian eras?

He has not had the same national staying power in people’s minds as Constable

and Turner.

His

grandfather was a prominent Quaker and Member of Parliament, and later made

Lord of Monkswell, a county in Devon in the south of England. His early life in

a successful family was unremarkable. He would marry twice, both times to the

daughters of famed British biologist and ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ Thomas Henry Huxley

— the man who coined the term agnostic and likely influenced Collier’s own

beliefs on religion. Had it not been for his remarkable skills with a brush,

John Collier would have faded into history, a footnote in the family tree of

minor English nobility. His skill though is beyond question.

The

Darkness at the Heart of Man

I’ve tried

for a long time to think what it was I loved about Collier’s work. Many of the

scenes are mythological or depict real individuals such as Rudyard Kipling

(author of the Jungle Book) or Charles Darwin, but many others depict people

who are no longer recognisable to us today, field marshals, surgeons and the

wives of rich men. Then, I compared his work to my other favourite English

artist, John Martin, who paints epic, often biblical scenes with a roaring

splash of vibrant colours that leave you awestruck.

It was

there that I found my answer. Collier’s focus on the individual leaves no room

to hide. You get lost in a Turner, Constable or Martin painting, but Collier’s

work grabs you by the throat and forces you to look. Take the below

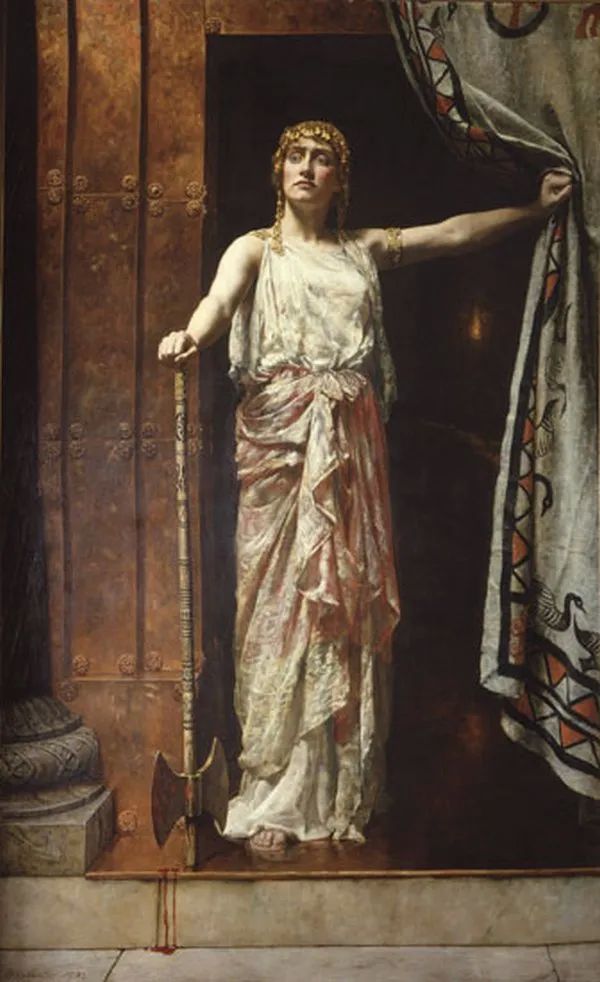

Clytemnestra after the Murder (1882). For those that don’t know the myth, Clytemnestra

is the wife of Agamemnon in the Iliad and mother of Iphigenia, the daughter

that Agamemnon kills so that the Greeks can set sail and reach Troy. After

returning home with a prisoner and concubine Cassandra, the oracle cursed to

offer true prophecies but never be believed, both are murdered by his

grief-stricken and near mad wife, Clytemnestra.

Clytemnestra

It is a

horrific story, and it made for a horrific painting. Clytemnestra stands

defiant, covered in blood, drawing the curtain aside, inviting us to peer into

the darkness in search of her victims. But it’s the eyes that hint at what I

think is a one of Collier’s greatest depictions in his work — madness, darkness

and the unconscious mind. What Carl Jung would later call, the ‘shadow’, that

repressed part of our minds liable to burst forth at any moment, especially in

the restrained Victorian society of Collier. There is nothing romantic in

Clytemnestra’s eyes, no tormented soul to grieve for. We are peering into the

eyes of madness, a Lady Macbeth pushed over the edge. This is the raw

unconscious mind.

Lilith

This is

what I love about Collier’s work and what makes him stand out. Though his

subjects were not uncommon, famous individuals and mythology have been the

bread and butter of artists for centuries, the unease he gives the viewer by

the weaving of the unconscious mind into his paintings is electrifying. Lilith,

1887, the first wife of Adam. She is coiled by the snake, who is

presumably Satan, nude and almost caressing him with her cheek. To the deeply

religious Victorians, this would have been scandalous, yet Collier depicts a

woman enjoying her pleasures here. Lilith is shown to embrace her sin, her

darkness, and relish in the gratification it gives her. The conscious gives way

to the unconscious, the shadow rules.

As we saw

with Clytemnestra, unapologetic women are something of a theme for him. In

Circe, (1885), the sorceress of the Odyssey, the titular woman is nude beside a

tiger and leopard, alluring and enticing, curious about her observer and

inviting you to approach, while the darkness lingers in the background,

menacing you all the same. Lady Godiva, another quasi-mythical English figure —

an English noblewoman who rode naked through her husband’s town in protest of

his high taxing of the citizens — also shows these themes. Lady Godiva is

caught off guard by the viewer, her shame finally overcoming her in her private

moment, the unconscious recoiling at what she’s endured, yet she has defied her

husband all the same.

Lady Godiva

Perhaps no

two works show the unconscious so strongly as The Confession, 1902, and The

Priestess at Delphi. Too vastly different subjects, yet both oozing menace and

unease. The hellfire red of The Confession matches the devilish red of the

Priestess of Delphi’s robe, the light from which reflects downward, giving her

closed eyes an almost ember like quality. In The Confession, a man and woman

seem resigned to something they’ve heard, shattered by unexpected news, while

the priestess awaits her vision from the gods, the vapours of the temple

creeping through the floor so that she can receive their words.

Priestess of Delphi

In a

society shaken to its foundation by the work of Darwin, Nietzsche’s nihilism

and Freud’s unconscious, is it any wonder that darkness haunts the canvases of

Collier? Collier was himself an agnostic, following his father-in-law Huxley,

be he was no fool. God had left a void in man, just as he had left a void in

art and Collier filled that with the unconscious. His subjects are confronting

and do not explain their actions, because by their very nature they cannot. The

unconscious is not a rational being that expresses itself in neat Victorian

prose. It lingers, repressed in the background of polite society, threatening

us, until it bursts forth in the uncompromising stare of a Clytemnestra, the

sensual evil of Lilith, the shame of Lady Godiva, or the incomprehension of a

couple unable to bear anything but the dim glow of the firelight.

Collier

captured more than the landscapes and people of his contemporaries and

predecessors. He captured the unspeakable and unknowable face of us all.

John

Collier: Victorian Britain’s Darkest Artist.

The horrors of the unconscious mind. By A Renaissance Writer. Medium, March 16, 2022.

The

Honourable John Maler Collier (1850-1934) was a British painter and writer. He

painted in a style inspired by the Pre-Raphaelites and the neo-classicists and

became one of the most prominent portrait painters of his generation. Collier

deserves a posting to himself on this blog as his image, Tannhäuser in the

Venusberg (1901), forms the cover of my 2021 book, Aphrodite- Goddess of Modern

Love. I chose the image for the fact that it represented one aspect of

Aphrodite- that of her as an independent and self determining female. In the

words of the Velvet Underground’s song, Venus in Furs, she is seen here as “the

imperious.” She may not be about to whip and humiliate Tannhäuser, as Wanda

would have done in the novel Venus im Pelz, but she nonetheless has the young

knight as her subject and slave.

Collier was

from a prosperous and successful family; his father was a judge. He studied

painting at the Slade School under Edward Poynter for three years, before

attending the Munich Academy from 1875, followed by a time studying in Paris.

Through his father, he was introduced to the established painters Alma-Tadema

and Millais, who provided guidance and encouragement. Collier first exhibited a

figure study at the RA as early as 1874, something which soon established him

as a portraitist. He also met his first wife at the Academy school. She sadly

died after the birth of their first child; Collier then, much against

prevailing convention and society approval, married her younger sister, a

ceremony which had to take place in Norway as it was prohibited in English law.

Interestingly, Collier’s greatest successes as a painter came from his “problem

pictures” in which he tackled social problems and the dramas of ordinary life-

The Prodigal Daughter (1903) and Sentence of Death (1908) speak for themselves.

An Incantation

During his

career, Collier benefitted from his social background to receive commissions to

paint a lot of the leading men of the British Empire, from which he made a

“comfortable if uninspiring living.” These pictures are a succession of dull

figures in black suits and khaki; his portraits of society ladies and children

are rather more appealing (he painted some 1100 in his lifetime). Far more

interesting and memorable, though, are his historical and mythical scenes, such

as Lady Godiva, 1898, Circe, 1885, Lilith, 1887, and Clytemnestra, 1882. These

can be melodramatic as well as colourful. His classical and oriental scenes are

without doubt vibrant and sexy, his heroines often being fearfully

self-contained and determined women. As art historian Christopher Wood rightly

observed, Collier had a “distinct taste for the theatrical.”

For such an

establishment figure, Collier’s views on morality and the Christian religion

were surprisingly outspoken for the time and his position was decidedly

sceptical about a deity. He was a forthright rationalist, once described as

‘quietly ruthless’ in his manner. Perhaps this was why he seemed to imbue so

many of his pagan scenes with such a vital spirit, as if prepared to concede

that their deities might be real, that their practices might be as valid as

those of the established church, that magic and prophecy might work, and that

supernatural entities might exist throughout the natural world. If nothing

else, the ancient ceremonies he imagined look lively and fun and he endowed his

nature spirits with life and charm, whilst his females and goddesses have a

quiet power and confidence.

As some

readers may be aware from my other WordPress blog, British Fairies, I also

write about British folklore, so that part of my admiration for Collier comes

from his frequent handling of native legends and stories alongside the

classical myths. As his rendition of Halloween shows Collier appreciated the

continuing emotional power of folk beliefs.

Many of

Collier’s images seem to stand outside any specific chronological period or

identifiable historical era. For instance, Stepping Stones, shown below, could

well represent a young girl of the 1920s, but her dress is vaguely classical,

making it possible that we can see her as yet another Greek naiad alongside the

Water Nymph depicted beside her.

For me,

there is far more vitality and interest in Collier’s depictions of myth and

antiquity than in most of his pictures of the great and the good of the late

British Empire. If nothing else, his imaginary worlds are places where women

wield considerable temporal, religious and magical power- they are all, in a

sense, a manifestation of Venus the imperious.

Suggested

further reading includes Christopher Wood’s Olympian Dreamers and William

Gaunt’s Victorian Olympus. For more information on late nineteenth and early

twentieth century art history, see my books page.

All Halloween

The

Imperious Venus- the art of John Collier, By John Kruse. John Kruse Blog Wordpress, November 24, 2021.

In the early twentieth-century, the “problem picture” became a popular craze at the Royal Academy exhibitions. Deliberately ambiguous—and often slightly risqué—scenes of contemporary life, these pictures encouraged eager audiences to offer competing interpretations of the puzzles they posed, both at the Academy itself and in newspaper coverage and competitions.1 John Collier’s painting The Prodigal Daughter, exhibited at the Academy in 1903, was one of the first and most popular problem pictures, sparking conversations about new roles for women and the purpose of art in the early twentieth century

A young

woman stands proudly—even haughtily—at the doorway of a humble parlour,

decorated with old-fashioned prints and a modest round table. The daughter has

interrupted her ageing parents at their evening reading, as the father looks up

from his book and the mother slightly rises from her chair. The prodigal’s fine

flowered dress and red sash are in sharp contrast to her parents’ drab

clothing, a difference emphasised by the dramatic lighting which illuminates

her unbound hair and gold jewellery, and plunges the older couple into shadow.

Visually

and thematically, the picture is a witty and thoughtful reworking of Hunt’s

“modern moral subject”, The Awakening Conscience, exhibited at the Academy in

1854. Hunt’s picture shows the spiritual reawakening of a “fallen woman”, who

rises from her lover’s lap as she realises the error of her ways. Collier

subtly reworks the furnishings of Hunt’s domestic interior: the piano, the

prints, the mirror, even the tangled skeins of yarn all reappear, but are now

dingy and old-fashioned. The elderly parents even seem to reprise Hunt’s young

couple: in each pair, the man sits in a chair, turned to the right, arm resting

on the armrest, while the woman reacts more quickly than her partner, caught in

the act of rising to a stand. But if Hunt’s protagonist’s spiritual awakening

offered a clear moral message about sin and repentance, Collier’s picture is

less comprehensible, not least because this prodigal looks most decidedly

unrepentant.

Reviewers

struggled to devise a narrative that would make sense of both the picture and

its seemingly religious title. In the words of one puzzled critic:

“ From the

title of the picture, it may be inferred that her career has been similar to

that of the Prodigal Son of the parable, but she has none of his repentant

humility, and has seemingly not been reduced to the straits which he had to

face.”

Viewers imagined various stories to make sense

of the situation, and as one reporter noted, “there is always a group gathered,

discussing the artist’s meaning and debating as to whether the bedizened young

lady is supposed to have just returned home or to be on the eve of departure.”

As they

worked to make narrative sense of the picture, critics grappled with the

changing roles for and expectations of women in the early twentieth century.

For some viewers, the very idea of a prodigal daughter still carried the sexual

connotation and inevitable consequences inherent in the Victorian idea of the

“fallen woman”. M.H. Spielmann described her in damning terms as a modern type:

“ the

Prodigal Daughter of to-day, whose feminine heart, once abandoned and wholly

corrupt, knows no redemption, but glories in sin, and is conscious only of

enjoyment as to the past, and as to the future persistence in the lost path on

which she has entered.”

But others

questioned both the reason for the daughter’s decision to leave home, and her

emotional relationship to her parents. Many critics suggested she might have

left home to pursue a career on the stage, and The Daily Telegraph added the

possibilities that she was a singer or a painter. The woman’s magazine The

Gentlewoman even interpreted the picture as a young woman’s justified rebellion

against a reactionary and unpleasant home life, describing the father as “a

bourgeois Casaubon” and concluding that the beauty of the girl’s face “is so

tempered by refinement as to suggest that her time has been spent in running a

tilt against convention rather than swine-herding.”

While

Collier himself never embraced the label of the “problem picture”, throughout

his career he defended his paintings as explorations of real emotion and

character designed to make viewers engage with the depicted situations. In a

retrospective interview, he looked back to “the first of these pictures of mine

that was dubbed ‘problem’”, and described his own perspective on the

development of The Prodigal Daughter:

“There I

undoubtedly tried to tell a dramatic story and, I think, a human one. There are

the eminently respectable lower-class parents, and there bursts in upon them a

flaunting beauty who, unlike the prodigal son, is obviously unrepentant. The

girl is unquestionably saying, “Well, what are you going to do about it?” The

father, perhaps a local preacher, is stern and unyielding; the mother is

bending forward, yearning for her child. There were, for me, many problems in

that picture. How to get suitable models for the three actors in this little

drama; how to make the room and its furniture expressive of the home life from

which the girl had broken away; how these people would have looked and acted,

and, a more purely pictorial point, what would have been the effect of the one

lamp which is the sole illumination of the three figures.”

Collier

emphasises the narrative and emotional power of the painting, but some of his

language also points to the changing artistic values of the early twentieth

century, as questions of colour, light, form, and facture came to seem more

important to at least some viewers than story or moral.

1903 The

Prodigal Daughter and the Problem Picture. By Pamela Fletcher. The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition : AChronicle, 1769-2018. 2018

The great majority of narrative paintings refer to well-known oral or text narratives, but a few do not. British painters of the late Victorian period not only made a speciality of painting narratives which were not known to the viewer, but created a sub-genre of problem pictures, whose whole purpose was to encourage speculation as to their narrative.

Precursors of these problem pictures started to appear around 1850, but they became most popular and problematic over the period 1895 to 1914, particularly those of John Collier. These became popular topics of discussion among the chattering classes, and their debate and possible narratives were even covered in the press of the day.

This

article traces their origin, and provides a few examples by the master of

problem pictures, John Collier – whose Sleeping Beauty I discussed earlier.

William

Holman Hunt (1827-1910), The Awakening Conscience (1851-53)

Probably

the best-known precursor to the problem picture, and one of the earliest,

Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience (1851-53) shows a domestic conflict.

Originally, the woman’s face was even more anguished, but shock among critics

encouraged Hunt to moderate her facial expression to that now seen.

Careful

examination of the painting reveals many cues to a more controversial

narrative, of a ‘kept’ mistress and her lover in disagreement. There is no

wedding ring on the fourth finger of her left hand, which is a focal point of

the picture. The room itself is furnished gaudily and in poor taste, and

contains evidence of the woman’s wasted hours waiting for her lover: the cat

under the table (which symbolically is shown toying with a bird), the clock

inside a glass on top of the piano, the unfinished tapestry, and so on.

That said,

what is the underlying narrative? Is this just the regret of the ‘kept’

mistress, and her desire for a more regular relationship and family?

William

Frederick Yeames (1835–1918), And when did you last see your Father? (1878)

And when did you last see your Father?

Yeames’ And

when did you last see your Father? is set in the English Civil War, as

indicated by the Puritan dress of conical hats and plain clothes. This

contrasts with the opulent silks of the mother and chidren, who are clearly

Royalists. The young boy is being questioned, presumably as given in the title,

for him to reveal the whereabouts of his Cavalier father – an act which is

bringing great anguish to his sisters and mother.

Setting

most of the cues to the narrative in the dress and disposition of the

participants makes it a greater problem, although here with sufficient

interpretative information the problem is readily soluble.

William

Quiller Orchardson (1832-1910), Hard Hit (1879)

Orchardson’s Hard Hit is more difficult to solve. The

fashionably-dressed young man about to open the door on the left is walking

away from a group of older villains, who have stopped at nothing (including

perhaps cheating) to beat him repeatedly at cards, and have relieved him of his

wealth.

This is told well using classic Alberti techniques

such as facial expressions, but most importantly here by body language and

direction of gaze. Orchardson’s model provided the inspiration, when he arrived

dejected at the studio one day and revealed that he had been ‘hard hit’ himself

the previous night.

William Quiller Orchardson (1832-1910), The First

Cloud (1887)

His The First Cloud is the last of a series of three

paintings about unhappy marriage, specifically a young, pretty bride who

marries an older man for his wealth. With their faces largely concealed, the

narrative relies on their body language and physical distance. When it was

first exhibited, the following lines from Tennyson were quoted:

“It is the little rift within the lute

That by-and-by will make the music mute.”

John Collier (1850–1934)

By the 1890s, Collier was looking for something beyond

the portraits which had made him successful, and exploring different ways of

making history painting more relevant to the social issues of life at that

time.

The Garden

of Armida (1899) was an early attempt to show a traditional historical subject,

that of Rinaldo in Armida’s garden from Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered (see this

article) in a contemporary setting and dress. In doing so, he posed the problem

as to whether the viewer was to see some more modern narrative beyond Tasso’s

original. It was not well received, and Collier decided to try more direct

problem pictures instead.

The

Prodigal Daughter (1903) was far more successful, and remains one of Collier’s

best-known works. An elderly middle-class couple are seen in their parlour in

the evening, surprised by the interruption of their prodigal daughter, who

stands at the door.

This

immediately sparked debate over the role of women in the modern world, the

nature and scope of their family responsibilities, and changing class

boundaries. Collier went to great lengths to capture the expressed emotions, in

terms of the daughter’s facial expression, and the contrasting body language.

The daughter is seen as a ‘fallen woman’, thus part of a popular mythology of

the time. But far from appearing fallen and repentant, she stands tall, proud,

and wears a rich dress.

The

resulting discussion spilled over from art gossip columns into more general

editorial and comment sections of the press.

A few years

later, his Mariage de Convenance (1907) was another painting which received

extensive media coverage. In contrast with Orchardson’s early more obvious

treatment of the problem of marriages of convenience (which were often also

arranged marriages), Collier poses a real problem.

The mother,

dressed in the black implicit of widowhood, stands haughty, her right arm

resting on the mantlepiece. Her daughter cowers on the floor, her arms and head

resting on a settee, in obvious distress. Perhaps the daughter has been (or is

to be) married into money to bring financial security to the family, now that

the father is dead?

Collier

himself offered a slightly simpler version of that, when finally tackled by the

press, which omitted reference to the father’s death.

By the time

that Collier showed his next problem picture, The Sentence of Death (1908),

they had become established as a familiar feature of the annual Royal Academy

exhibition. This painting at first disappointed the critics, but quickly became

very popular. Sadly the original work has not lasted well, and I rely on a

reproduction made at the time.

At a time

when disease and death were prominent in everyday life, this painting might

seem quite ordinary. A young middle-aged man stares blankly at the viewer,

having just been told by his doctor that he is dying. The doctor appears

disengaged, and is reading from a book, looking only generally in the direction

of his doomed patient.

Unusually

for Collier’s problem pictures, and for paintings showing medical matters in

general, the patient is male. This led to speculation as to the expected male

response to such news, and questions as to what condition might be bringing

about his death. There was even debate about interpretations of the

doctor-patient relationship.

The First

World War changed Britain, and British art, dramatically. One of Collier’s last

problem pictures was Sacred and Profane Love (1919), which drew attention to

women’s problems again. On the left, sacred love is shown in a modestly if not

dowdily dressed plain young woman, and on the right, profane love as a

‘flapper’ with bright, low-cut dress revealing her ankles, flourishing a

feather in her left hand. The suitor is shown reflected in the mirror above, a

smart young army officer.

Although

not as enigmatic as his earlier works, Collier remained very topical, achieving

his narrative using dress and composition, rather than facial expression.

The

remaining problem paintings by Collier are an even greater problem in that I

have been unable to find any further details of them, or of the artist’s

intended narratives.

In The

Laboratory (1895), there is clearly a narrative between the old alchemist and a

young woman, who is trying to take an object from the man’s right hand. This

may be a reference to a text narrative which Collier was exploring prior to his

real problem pictures.

The Sinner

(1904) is most probably another problem picture, as it shows a woman, possibly

dressed in widow’s weeds, making an emotionally-charged confession. This begs

much further speculation.

Fire (date

not known) shows a young woman, sat up in bed, afraid by the bright warm light

of a fire, presumably one which is in the same building and putting her into

danger. It is not clear why she is not doing anything to try to escape, though.

The Minx

(date not known) shows a femme fatale holding what might be a mirror in front

of her. Unfortunately the condition of the painting is not good, and its

narrative now more obscured that it was.

Conclusions

This

unusual and short-lived sub-genre exploited the ambiguities that arise in

narrative paintings to elicit debate and speculation. As Fletcher points out,

its themes were the problems of the day, particularly those of women, their

roles, and sexuality. Although other good narrative painters have achieved

similar depth in their works, Collier seems to have been unique in his

development of such problem pictures.

The Story

in Paintings: Problem pictures. By Hoakley. The Eclectic Light Company,

February 19, 2016.

A Fallen Idol

In 1913, John Collier contributed A Fallen Idol to the annual Royal Academy summer exhibition. The painting depicts a young woman crouched in grief or shame at the knee of a slightly older man, who looks up and out into the distance, presenting his impassive face for our inspection. Viewers seized on the picture and its title, offering competing – and often facetious – answers to the question of which of the two was the ‘fallen idol’. The World noted that there was ‘always a little crowd of speculators’ before the picture, and even after nearly three months of exhibition, public interest remained high enough that The Times published Collier's response to ‘a correspondent who asked him to “solve the riddle of his picture”’. When the tabloid paper the Daily Sketch sponsored a competition for the best interpretation of the ‘problem picture’, the editors were inundated with responses ranging from the serious to the satirical. Readers suggested that the woman was ‘a bridge fiend who had become overwhelmed by debt … The unhappy lady was also alleged to have: neglected her dying child; confessed that she was a militant suffragist; ruined her husband's digestion by her bad cooking’. He, in turn, was ‘held to be a gambler, forger, cheat at cards, victim to drugs or drink, and even a Cabinet Minister’. While the majority of respondents believed adultery (usually the woman's) was an issue, even this did not resolve the picture, as viewers debated questions of motivation and likely outcome. Had the husband neglected his young wife? Would he accept his share of responsibility for their marital difficulties, or would the matter end up in divorce court?

This rich

mixture of playful speculation and moral evaluation bears all the hallmarks of

gossip. And, indeed, the best way to describe the reception of A Fallen Idol is

to say that viewers gossiped about the depicted characters as if they were real

people. The Daily Sketch competition was, of course, an attempt to generate

publicity and attract readers, and the rhetorical device of gossip offered a

veneer of respectable distance from lowbrow responses. Yet the very fact of the

paper's reliance on gossip as a publicity device suggests that the possibility

of this kind of reading was a significant part of the painting's appeal. Such

press accounts thus provide tantalising evocations of the picture's ephemeral

social life: exhibited before large crowds at the Academy and widely reported

on in the press. In this article, I suggest that taking gossip seriously as a

mode of engagement with art both amplifies our understanding of the meanings,

functions, and pleasures of narrative painting, and suggests specific

connections between exhibition culture and the meanings of pictures.

Gossip is a

mode of conversation, ‘idle, evaluative talk’ about other people, fuelled by

speculation and often containing a hint of scandal or impropriety. While gossip

is commonly identified with the discussion of people whom one knows, the term

can also be extended to the discussion of people not directly known to the

gossipers, such as celebrities, royals, or – I argue – the invented characters

in narrative paintings. As Reva Wolf and Gavin Butt have argued in their

respective work on Andy Warhol and Larry Rivers, pictures themselves can be

acts of visual gossip, displaying artistic identities, and constituting subgroups

of viewers in the know. Gossip is also, as the case of A Fallen Idol makes

clear, a conversational mode of response generated by viewers, exchanged at

exhibitions, in the press, and – it is perhaps safe to assume, though we have

little direct evidence – in other social settings. As recent scholarship in

anthropology, sociology, and psychology has demonstrated, such gossip serves an

important social function, creating and solidifying individual and group

identities through the mutual investigation of social codes. Recognising both the social function and the

potential subversiveness of gossip, historians have begun to use gossip as a form

of historical archive, suggesting that it may be particularly valuable for

recovering the voices and perspectives of those generally excluded from more

authoritative sources. But gossip is, by its very nature, fugitive: filled with

inside knowledge and jokes, generally communicated in oral conversation, and

only rarely preserved in written form. How, then, might we begin to recover a

history and theory of gossip as a mode of engagement with narrative painting?

Located at

the intersection of the Victorian narrative tradition with the modern mass

media, the problem pictures of the 1910s generated a rich archive of gossipy

reception. Narrative paintings of modern life had been perennial popular

favourites at the mid-Victorian Royal Academy. The problem picture extended

that tradition into the late- nineteenth- and early- twentieth centuries,

transforming the highly detailed moralising paintings of the mid-Victorian era

into ambiguous and often slightly risqué paintings of modern life that invited

multiple, equally plausible interpretations. Viewers and critics responded

enthusiastically, crowding the Academy galleries and filling the pages of

newspapers and magazines with possible explanations. In the early years of the

twentieth century, the term ‘problem picture’ was coined by the press to

describe this phenomenon, a fact that points to the critical role of the

expanding periodical press in creating, sustaining, and extending the conversations

the pictures provoked. Although the popularity of the problem picture peaked in

the first decade of the twentieth century, artists continued to use the form in

the 1910s and beyond in order to engage with topical questions of morality and

politics, including divorce law, anti-Semitism, and drug use. Indeed, while the

problem pictures of the 1910s – with titles like Out of It and Cocaine – were

not granted much aesthetic legitimacy, this very lack of authority allowed for

an even greater level of popular response and speculation, recorded in the

chatty art coverage of the tabloid press, viewers' entries to newspaper

competitions, and occasional letters to artists – in other words, the

discursive traces of historical gossip.

Such

narratives in the press were not, of course, identical to any actual viewers'

vocalised responses, and the available archive is necessarily constructed

within journalistic and critical texts. The press thus does double duty,

constituting, at least in part, the mode of response it names as gossip, and

serving as our primary representation of it. But the consistent deployment of

the rhetorical form of ‘gossip’ as a frame for the representation of problem

pictures and their reception across a wide range of newspapers and journals –

from working-class Sunday papers to Society magazines, from tabloids aimed at

the lower-middle classes to the solidly established dailies – does point us to

the visual and historical particularities of these pictures, which encouraged

such a mode of response. In what follows, I use these pictures and their

reception to establish a taxonomy of gossipy modes of engagement with narrative

painting, and to investigate the specific functions of each mode. The result is

both an examination of a specific set of pictures and a case study that

illuminates some of the complex relations between the social experience of

viewing art, the media reporting of exhibitions, and the meanings of narrative

pictures, at the very moment of their apparent eclipse in the early twentieth

century.

Gossiping

at the Royal Academy

Exhibitions

were, of course, far more than collections of pictures. The physical space of a

gallery, the kinds of pictures exhibited, the hanging of the pictures, and the

composition, density, and motivation of the audience all shaped an exhibition's

culture, the physical and social environment that influenced viewers'

interactions with the art on view and with one another. Narrative painting,

particularly the problem picture, flourished in what we might call the Royal

Academy's culture of conversation, and the contours of that experience are

critical to understanding its reception. While the Academy's audience and

prestige declined over the course of the nineteenth century, it remained a

major social and artistic event well into the twentieth century, as the

extensive coverage of the 1905 opening-day private view attests: ‘From ten

o'clock onwards the great quadrangle … began to fill with carriages, and Watts’

giant equestrian statue of “Physical Energy” was soon besieged with footmen and

horsemen of another kind. The long and crimsoned staircase up to the vestibule

was lined with palms and flowers – lilies, roses, and glowing geraniums'. As

reported in 1907, the crush of visitors continued inside the exhibition: ‘At

four in the afternoon the crowd was so thick that it was only possible to move

round the rooms with the greatest difficulty. In front of many of the pictures,

the artist, surrounded by a knot of friends, was modestly answering questions,

explaining details, or receiving congratulations. Other knots of people discussed

golfing prospects or week-end trips’. Before particularly popular pictures, the

conversation could be deafening, as the Morning Post reported in 1903: ‘The

noise at four o'clock in the Third Gallery, where everyone was talking at once,

was extraordinary’.

Discussion

of the pictures extended beyond the physical space of the Academy and the day

of the private view, continuing in other social settings and in the pages of

the periodical press. The most commonly recognised motive for attending the

Academy was to get ‘conversation’, and reviews of the Academy in daily papers

often focused on this aspect of the exhibition, asking ‘And what about

the … pictures? What is going to be the most eagerly discussed, and what can we

talk about, at dinners, or (if we are dancing men) to girls who are so hard to

talk to about anything but the Academy, when one is “sitting out” with them’. As a critic for Reynolds's Newspaper

explained:

“ The

importance of the Academy is social rather than artistic. It has become a legalised

and highly respectable topic of conversation. We must all carry about with us a

stock of opinions about the works of the artists who paint for this exhibition.

These opinions are as necessary for each gregarious individual as a pocket

handkerchief or a cigarette case. They do to pull out and flourish on awkward

occasions: the aged don't mind them and with the young they often serve as a

prelude to sweeter things.”

While male

viewers were jokingly encouraged to get conversation to fill up awkward moments

or to advance their flirtations, women were instructed to take the social

duties of conversation more seriously. As the ladies' magazine the Queen

advised its readers in 1898, ‘A Royal Academy exhibition, like a new play,

creates conversation. It is a subject on which anyone can dilate at a dinner

party or an afternoon tea’. Popular pictures, it seems, served as topics of

gossip among various kinds of social groups, from friends attending the Academy

together to relative strangers meeting in a range of social situations. The

periodical press both claimed to reproduce such gossip and participated in it,

extending its reach beyond the walls of the exhibition. Located in both serious

art reviews and in more popular coverage of the Academy as a social event, such

reported gossip could both offer the uninitiated reader a view of the

fashionable Academy and serve as a foil to the more elevated appreciation

evinced by the critic himself.

The Railway Station

The

Academy's culture of conversation had important implications for how viewers

approached individual paintings and the kinds of paintings to which they were

drawn. The narrative paintings of modern life that became popular at the

Academy from the 1850s onwards presented the contemporary world in naturalistic

form, inviting viewers to relate to the picture through the lens of their own

experience. Writing about William Powell Frith's modern-life scene The Railway

Station in 1862, Tom Taylor described the parameters of this kind of response:

‘There is nothing here that does not come within the round of common

experience. We all of us are competent to understand these troubles or

pleasures, anxieties or annoyances: There is no passage of these many emotions

but we can more or less conceive of ourselves as passing through’. Such

discussions tended to focus on emotional response and moral evaluation, as

viewers engaged with even the most unlikely painted characters as if they were

real people. In 1907, a report in the Daily Mail on the popularity of Frank

Cadogan Cowper's painting of the devil disguised as a troubadour singing to a

group of nuns offered a vivid example of this kind of reading, extended even

beyond the parameters of what might generally be considered modern-life genre:

“He has

fascinated them,” said one severe lady spectator with eyeglasses.

“And they

think they are converting him,” said a young man by her side.

“I think,”

said an American lady slowly, “that girl who is laughing is real fast.”

And so

throughout the afternoon the comment went on.””

Such readings

of paintings in terms of the depicted individuals' emotions and characters move

aesthetic response into the realm of gossip in intent and function: ‘idle,

evaluative talk’ about other people, exchanged to fill time and build

relationships, and serving to test and demonstrate moral beliefs and values.

If all

narrative painting offered this potential, however, problem pictures

deliberately foregrounded it. Artists used ambiguous narratives and topical

subjects to situate their pictures in the realm of gossip, capturing public

interest through their creative reworkings of contemporary scandal and media

events. In return, viewers and critics generated multiple stories about the

characters in the paintings, inventing motives for their actions, dissecting their

characters, and predicting their futures. As one humorous account of a reading

of A Fallen Idol indicates, such responses could become quite elaborate: ‘The

thing's obvious of course; the woman's done it. Her husband doesn't mind much

either judging by his expression. He's simply trying to remember the address of

his lawyer, and whether that rich American widow who gave him the “glad eye”

over the table the other evening really meant matrimony or – or not’. The tone

of the comment is revealing of the differences between these pictures and

earlier Victorian moralising narrative paintings. At a time of rapidly changing

aesthetic standards, when many critics were urging attention to the formal and

material qualities of the art work rather than its subject matter, at least

some artists, critics, and viewers at the early-twentieth-century Academy were

willing to treat narrative paintings of modern life as open-ended games rather

than didactic lessons, while the expanding tabloid press opened the door to extended

coverage of such playful interpretations. Eliciting readings such as this one,

problem pictures became the quintessential example of narrative painting as

visual gossip.

A survey of

these late problem pictures and their reception suggests three major modes of

engagement with gossip: topicality, intertextuality, and identification. Each

of these three modes has roots in earlier narrative painting, making it

possible to map the continuities and differences between the problem picture

and its Victorian forerunners in ways that are suggestive of a longer history

of gossip as a mode of engagement with narrative painting. Problem pictures

pushed the boundaries of modern-life genre, featuring incidents of suicide,

scandal, and crime inspired by the lurid stories of tabloid journalism. The

pictures thus became acts of gossip in themselves and elicited gossip about

individuals – real and fictional – in return. As part of their speculation

about invented characters, viewers also engaged in intertextual readings linking

different pictures, and making identifications between the depicted characters

and real individuals. In each case, gossip functioned as a linking mechanism,

forging connections between viewers, between pictures, and between public and

private interpretations of the world.

Topicality:

Gossip and the Discourses of Morality

Three

problem pictures were exhibited at the Academy in 1913 and each relied upon a

topical appeal, drawing on contemporary events in the news. Collier's painting

A Fallen Idol received the most coverage, both because the artist had pioneered

the form in the previous decade, and because the exhibition of the picture

coincided with a renewed attention to the question of divorce law. The

much-publicised release of the report of the Royal Commission on Divorce and

Matrimonial Causes in December of 1912 highlighted the question, among others,

of whether or not men and women should be equally and legally culpable for

adulterous conduct. Janice Harris has argued that the hearings of the Royal

Commission opened up a cultural space in which to challenge the stock Edwardian

story of divorce, in which the adulterous woman destroyed the marriage and was

justly punished, and the picture seems to have provided a similar opportunity. While

responses to the picture rarely mentioned divorce directly, the question of

adultery and its effects were central to the picture's reception. The solidly

middle-class newspapers The Times and the Daily Telegraph concurred that ‘the

puzzle is this time no puzzle at all’, assigning guilt to the young wife and

assimilating the picture to the tradition of ‘fallen woman’ paintings. In contrast to the inexorable narrative of sin

and suicide that characterised the mid-Victorian fallen woman tale, however,

the possibility of reintegration into the family and respectable society is

suggested in these accounts, and The Times even proposed that the painting

‘might also be called, “Will he forgive her?”’ The woman's magazine the Queen,

in contrast, read the question of guilt as genuinely open-ended, asking ‘Who is

the fallen idol, the woman who crouches with bowed head by the man's knee, or

the man who looks sadly towards us above her stooping form?’, perhaps

suggesting a breakdown along gender lines in readings of the picture.

Tabloid

papers aimed at lower-middle-class readers were the place where the picture's

ambiguity was most fully explored in terms of gender and class. This was, in

part, because the format of such papers – focused on human interest news

snippets and readers' letters – was perfectly poised to exploit the playfully

risqué gossip that the picture could generate. In an article announcing the

competition for the ‘most convincing explanation’ of the picture, the Daily

Sketch compiled a list of responses, with female respondents including ‘Lady

Bland Sutton’ and ‘a tea shop waitress’ agreeing on the woman's guilt, while ‘a

City policeman’ observed, ‘Looks as if the gentleman had been owning up a bit,

and his wife's fair upset to find he ain't a hero after all’. In a later report

on the results of the contest, the responses were categorised by verdict,

shifting the focus to the probable nature of male and female weakness.

Responses were equally divided between identifying the man and the woman as the

sinner, but as the editors pointed out, ‘it is interesting to note that while

the woman's fall was in most cases attributed to passion the man's fault was

almost invariably of another order’, generally financial one. Perhaps the

strongest subtext of the article, however, is its emphasis on the inclusiveness

of the phenomenon. The results were introduced with the comment that ‘Fantasies

based on the picture came in from readers of all sorts and conditions. The

effort of a countess was followed by one from a pavement artist’, reassuring

the lower-middle-class readers of the Daily Sketch that their interest in the

pictures was shared by the highest reaches of society. In contrast, the Society

magazine the World distanced its readers from the ‘average man or woman’ to

whom such pictures appealed, and prophesied that ‘when the Academy supplements

reach our Colonies and Dependencies Mr. Collier will receive again many letters

from farthest India and Africa asking the nature of the crime of the lady’,

locating such viewers as far as possible from its fashionable readers.

In the face

of such speculation, Collier was eventually moved to intervene in the public

discussion. In a newspaper statement about the painting, he identified the wife

as the guilty party, but opened the door to conjecture about the causes and

effects of the transgression: ‘It is a young wife confessing to her middle-aged

husband. The husband is evidently a studious man, and has possibly neglected

her. At any rate, the first thought that occurs to him is, “Was it my fault?” I

imagine he will forgive his wife’. Collier's later comments on the picture

suggest that the painting was a quite deliberate intervention in the debate

over divorce law on the side of more sympathy for women: ‘To judge from the

correspondence I received, a good many people were interested in the question

whether the husband should or would forgive his wife. I think most of my

correspondents hoped that he would. Of this result of my picture I felt

distinctly proud’.

Out of It

If A Fallen

Idol engaged current social debates in a fairly substantive fashion, other problem

pictures at the Academy in 1913 were more closely linked to tabloid narratives

of melodrama and political scandal. Depicting a young woman in evening dress

lying unconscious or dead beneath some bushes, Out of It by Alfred Priest resonated

with two contemporary tragedies: the shooting and death of the Countess of

Cottenham while hunting, and the murder of a young domestic servant, Winnie

Mitchell, whose body was found buried in the woods. The artist himself located

this picture within the context of these two recent events, and justified its

sensational aspect with the claim that ‘life itself gives us these subjects’.

He went on to say that his subject was drawn from a similar source: ‘My picture

was inspired by a newspaper report five or six years ago. A beautiful girl is

supposed to leave the card-table after a dinner-party. She goes out, just as

she is, in her evening gown, without a cloak or hat. A search party is

organised, but the body is discovered, so the report says, by a village urchin's

dog’. Priest's eagerness to locate the picture's origin in a newspaper report

suggests that the interest of the picture lay in the conversations it could

generate about contemporary events and people in the news. Both of the recent

deaths had generated substantial news coverage, and each was connected with a

whiff of scandal: The death of the Countess – who had divorced her first

husband, with the Count named as co-respondent – was surrounded by the innuendo

of suicide, or worse; while the death of the young servant girl implicated a

married man and was compared to a Hardy novel. In each case, there is the muted

suggestion that the woman's past has somehow caught up with her, an implication

of retribution that provides the animating element of moral judgment to

readers' and viewers' speculations.

Finance

A third

painting exhibited at the Academy in 1913 extended the problem picture's

topical reach into the masculine realm of politics and public life. Depicting a

‘group of Jewish financiers’ and ‘a fair-faced gentile’ facing one another

across the aftermath of a luxurious dinner, Edgar Bundy's Finance enjoyed a

popularity that was largely attributed to its ‘topical interest’. To many

viewers, the picture seemed to refer to the on-going Marconi affair, a

political and financial scandal in which the Jewish Isaacs family was accused

of nepotism and three cabinet ministers were accused of illegal stock

speculation. A cartoon by E.T. Reed published in the Daily Sketch made the

connection directly, casting Winston Churchill as the affronted gentile with

the three accused ministers and three heavily caricatured Jewish businessmen

confronting him across the table. As the cartoon's caricatured rendering of the

Jewish men suggests, discussion of the scandal was fuelled by stereotypes of

greedy Jewish financiers and fears of an international Jewish cabal whose

influence on finance and politics exceeded any national government. Reviews of

the picture accordingly focused on its depiction of Jewish character and power.

In the mainstream press, many critics seem simply to have assumed the

transparency of the characterisation of the Jewish men; the Daily Mail critic

described the scene and commented: ‘The crude display of wealth and the

strained, keen expression on the faces of the Jews all turned on the young man

are wonderfully realistic’. Martin Hardie, writing in the Queen, noted some

heavy-handedness in the representation, but defended it as ultimately true both

to life and artistic intention: ‘Mr. Bundy has chosen unpleasant Semite types

because it suited his purpose; but they are types, none the less, and not

caricatures’. Such responses, however, did not go uncontested. Writing in the

Daily Telegraph, Claude Phillips – whose mother had been raised an Orthodox Jew

– noted that ‘for these life-size figures of opulent financiers … the most

repulsive types have been deliberately chosen and as deliberately exaggerated’,

and called the painting ‘a passionate assertion in paint of anti-semitism’.As

viewers identified the represented figures with real political actors, their

discussion of ‘race’, character and motive became a vehicle both for the evaluation

of specific politicians and entrepreneurs, and for the confirmation or

refutation of racial stereotypes and prejudices.

The strongest reaction against the painting came in a periodical aimed at Jewish readers. In a lengthy response to the painting entitled ‘A Disgraceful Picture’, the editors of the Jewish Chronicle reviewed the debate and charged the Academy with ‘moral retrogression’ for exhibiting the picture, accusing the institution of trafficking in journalistic public pandering and offering offence to Jewish viewers and artists. But it is the Academy's location as a place for the formation and exchange of social attitudes that is the cause of the most serious transgression: ‘The picture is blatant in its anti-Semitism and one has only to listen for a few minutes to the remarks of visitors to the Exhibition who stand in front of this picture to realise how unwise the Council of the Academy were in permitting this cartoon to find a place on their walls’. As viewers are drawn to the picture by the contemporary scandal and use it as an occasion to gossip and air their opinions, their beliefs are being shaped and directed by what the editors of the Jewish Chronicle see as the anti-Semitic perspective of the image.

Problem

pictures faded from the walls of the Academy during the years of World War I,

but reappeared in 1919 with a subject unimaginable at the pre-War

Academy. Cocaine by Alfred Priest) reverses the composition of A Fallen Idol,

with the man's head in the woman's lap, as she looks out and meets our gaze

with a troubled stare. But the circumstances are a world away from Collier's

respectable middle-class couple in distress. The woman sits in her dressing

gown, in a luxurious modern room in the early hours of the morning (the clock

on the side table reads 4.50). A young man in evening dress is slumped in her

lap, unconscious, returned home after a long night out on the town. The title

signals his presumed vice: cocaine. The drug was much in the news in the spring

of 1919. While it had long been available by prescription, it was only during

World War I that cocaine became identified with a drug underground and a

subject of public concern. The overdose death of the young actress Billie

Carleton in November 1918 and the inquest and trial that followed focused

attention on the dangers of modern drug use, and created a public understanding

of cocaine as ‘a moral menace’, particularly for vulnerable young modern women.

Contemporary responses situate the picture within this context, introducing its

topic by noting, ‘poor Billie Carleton can't be left alone’.

But, of

course, the picture does not follow the news account, as it is the man who is

the ‘dope fiend’ here. As Priest explained in an interview with the Daily

Mirror, the picture is based on a true story of a young wife who ‘discovered

suddenly that her idol had feet of clay’. Like Collier, Priest aimed to arouse

viewers' sympathy as well as their condemnation: ‘And you will observe that in

the picture her hand protects and sustains as it falls across the shoulders of

the crushed thing that is her husband’. While the gender roles have changed,

the dynamics of fallenness and forgiveness are the same as in Collier's Fallen

Idol, challenging viewers' stock stories and inviting them to write new ones.

As these

examples make clear, topicality and a symbiotic relationship with the press was

central to how the problem pictures of the 1910s worked. The motives of

individual painters of problem pictures varied, from Priest's self-conscious

attention-seeking to Collier's interest in serious social and political questions.

But they all shared the desire to use the pictures to spark discussion,

allowing viewers to engage with contemporary ‘moral panics’ and media scandals,

ranging from the most intimate matters of marital life to the motivations and

weaknesses of politicians and public figures. Artists drew on popular news

stories and scandals to engage viewers in their pictures and the press

publicised – and ‘problematised’ – the resulting pictures. The press was thus a

critical component in the circuit of meaning and interpretation, providing the

raw material for the pictures and then reporting on (and thus helping to create

and sustain) the conversations they generated.

This

multi-layered relationship with the press is one key difference between these

problem pictures and earlier examples of topicality in Victorian art. While

major current events such as the Crimean War and the ‘Indian Mutiny’ sparked

spates of paintings in the mid-Victorian era, they tended to use individual

incident and anecdote primarily to convey a larger theme – such as patriotic

sentiment – rather than to explore or dramatise the nuances of an individual's

life or psychology. William Powell Frith's modern-life panoramas and his

narrative series such as The Race for Wealth (1880), which rely upon viewers'

knowledge of contemporary events for their legibility and evoke multivalent

conversations, are closer in function, but still provide a legible and

(over)determined arc from sin through deserved punishment, and thus provide a

kind of moral and narrative horizon beyond which interpretation cannot easily

extend. The possibilities for reception

differed as well, of course, as the gossip and scandal driven human-interest

coverage of the New Journalism did not yet exist as either source or publicity

outlet for these modern-life pictures.

In

contrast, the problem pictures of the 1910s fused the tradition of modern-life

genre painting with new modes of journalistic sensation. Like the stories of

murder, sex, and accident that filled the pages of the mass circulation press,

problem pictures dramatised the everyday life of ‘ordinary’ people. The

pictures' theatrically posed moments of suspense left the details of the

characters' past, present, and future to viewers' imaginations, fuelled by the

habits of gossip and scandal fostered by the tabloid press. The elusive key to

each picture seems to turn on the psychology and motivation of the actors

represented: Was the wife's infidelity justified, and will it be forgiven? Are

the Jewish dinner guests shrewd businessmen or corrupt conspirators? How did

this promising young man fall prey to a drug habit? As an article in Truth

noted in 1878, such questions are the very source of gossip's popularity: While

discussion of the facts of a case is necessarily limited in scope, conjecture

about people's motives offered endless possibilities. This kind of gossipy

speculation plays a critical role in the formation and performance of moral

values and social norms. As contemporary psychologists John Sabini and Maury

Silver have argued, gossip ‘involves taking a stance about another's behavior –

behavior which could be our own, but isn't. To do that is to dramatize

ourselves: our attitudes, values, tastes, temptations, inclination, will, and

so forth’. At a time when gender roles were under pressure from feminist

challenges to Victorian ideals and the growth of the middle class was creating

fractures between its upper and lower reaches, class and gender were the

primary axes along which interpretations of these pictures were generated,

labelled and disseminated. As viewers indulged in the seemingly frivolous

pleasures of gossip before these pictures, they were staking claims to their

own identities and values, testing their moral codes against the problems of

modern life and the values of their peers.

Simultaneously,

this kind of gossip functioned as a link between the public and the private

worlds, as political scandals and legal questions of divorce or drug use were

understood and debated through the discussion of these invented characters'

lives, psychologies, and motives. As Patricia Meyer Spacks has argued in her

study of gossip and literature, gossip's power derives from its ‘liminal

position between public and private … Gossip interprets public facts in private

terms: The senator will not run for re-election because his wife will abandon

him if he does. It also gives private detail general meaning: The young woman's

drinking problem exemplifies the strain on women trying to do everything at

once’. Drawing upon public narratives of

law, celebrity, and scandal and using the techniques of narrative painting to

evoke relational responses from their viewers, these topical problem pictures

fused the public and the private through the medium of gossip.

Intertexuality

and Identification: Gossip and Social Networks

While

subject matter was perhaps the most obvious way in which artists engaged their

audiences, the gossipy appeal of problem pictures was not limited to

contemporary news events. As viewers focused on the characters in these

paintings, they made other kinds of links and connections between the

represented figures. A seemingly mundane ‘human interest’ story from 1913

suggests some of the ways viewers could relate to the painted figures. On 6 May

1913, the day after it ran a feature on A Fallen Idol, the Daily Sketch

featured Alfred Priest's Out of It on its front page. The story focuses on the

fact that the pictures share the same model – one Miss May Fagerstein, who is

pictured below the painting. While the article does not pursue them, there are

at least two potential modes of using this connection to extend the discussion

the picture aroused. On the one hand, viewers might follow the model through

the stories of the different pictures, interpreting them as episodes in the

life of a single character. On the other, the news story suggests the

possibility of seeing ‘through’ the pictures to the real personalities involved

in creating them. Both of these options – what I call intertextuality and

identification – expanded the potential for treating the characters in the

paintings as subjects of gossip and creating social networks of artists and

viewers.

Out of It

While the suggestion was not taken up in the accompanying article, the use of the same model opened up the possibility of reading the pictures in tandem, and attributing the young woman's death in Out of It to the crisis depicted in A Fallen Idol. This mode of intertextual reading was common in earlier problem pictures, as viewers turned the models into characters whose histories could be followed by attentive viewers. One reviewer recognised the unhappy husband of A Fallen Idol as a character in Collier's problem picture of 1908, The Sentence of Death, a scene of a young man in a doctor's office: ‘Perhaps the clue may lie in the fact that the young gentleman who supports the weeping woman is the same youth whose case was given up as hopeless by the doctor two years ago’. This identification, of course, opens up an entirely new area for speculation as to the couple's situation. The accused woman in Collier's problem picture The Cheat of 1905 was identified as appearing in several other contemporary pictures, including his problem picture of 1906, ‘Indeed, indeed, repentance oft I swore!’ The Daily Mirror saw the narrative connection as an obvious one: ‘Now we know that the cheat was the woman standing up. This year she is gazing into the fire, wishing she hadn't cheated’. Reading the pictures as successive incidents added a stronger moral element, illustrating a narrative arc from crime to remorse, if not punishment. This kind of intertextual reading both extended viewers' understanding of the depicted personalities as characters with histories and psychologies, and created a community of viewers who followed the stories year after year.

The Cheat

A variant on this kind of intertextual reading put the characters into conversation with the individuals depicted in the portraits that filled the walls of the average Academy. A long notice in Truth in 1906 made much of who precisely was the recipient of the whispered confession of Collier's penitent, whose ‘opulent physical charms’ offered ample evidence of the direction her ‘faults … must have probably tended’. The hanging suggested one scenario, in which ‘The elaborately “frocked” lady … is supposed to be exclaiming, just loud enough for “The Hon Mr and Mrs Douglas Carnegie with their sons John and David” to hear her in their full-size motor-car, “Indeed, indeed, repentance oft I swore!”’ But the reviewer was entranced by another possibility, complimenting the hanging committee for ‘having successfully resisted the temptation of moving [the picture] from Gallery VII to Gallery V … For then Mr Collier's grande dame would have been positively sighing out her vain expostulations in close proximity to the characteristic portrait of the Rt. Hon. Sir John Gorell Barnes, LL.D., President of the Divorce Division of the High Court of Justice’.