For generations, Neanderthals have been a source of fascination for scientists. This species of ancient hominim inhabited the world for around 500,000 years until they suddenly disappeared around 40,000 years ago. Today, the cause of their extinction remains a mystery.

Archaeologist

Ludovic Slimak and his team have spent three decades excavating caves, studying

ancient artefacts and delving into the world of Neanderthals – and they’ve

recently published provocative new findings. In this week’s episode of The

Conversation Weekly podcast, we speak to Slimak about how Neanderthals lived,

what happened to them, and why their extinction might hold profound insights

into the story of our own species, Homo Sapiens.

Neanderthals

migrated to Europe around 400,000 years ago from Africa, the birthplace of

humanity. Until now, the general consensus among archaeologists has been that

Homo Sapiens were a lot slower to leave Africa, only migrating to Europe

approximately 42,000 years ago and in one wave that coincided with the

extinction of Neanderthals.

But Slimak,

an archaeologist at Université Toulouse III - Paul Sabatier in France, has

published controversial new work that challenges this.

In 2022, he

published research from the Mandrin Grotte in the Rhône valley in southern

France, which suggested he’d found a Homo Sapiens tooth within Neanderthal

sediment layers. He explains:

“”We began to work in the middle of these

layers that were dated at 54,000 years, and then we began to find incredibly

modern Homo Sapiens technologies sandwiched between very classic Neanderthal

technologies.”

Slimak’s

subsequent research suggests that, rather than a single wave of Homo Sapiens

migration from west Asia to Europe, there were in fact three waves, the last of

which happened around 42,000 years ago. These findings are provocative: they

would rewrite the timeline to suggest that Homo Sapiens arrived in Europe about

10,000 years earlier than previously thought, and so co-existed with

Neanderthals for much longer.

What tools reveal

To

understand the factors that led to the extinction of Neanderthals and the

survival and dominance of Homo Sapiens, Slimak has also compared the tools

crafted by both species during the period they co-inhabited Europe. His

hypothesis is that examining the evolution of these tools and how they’re made

might provide clues into the differing fates of the two human species.

“If you

take Homo Sapiens tools or weapons technology, after you’ve seen a hundred of

these tools, they are precisely the same. So, we have a process of

standardisation, of production in series that is very specific to our species.

But now, if you take Neanderthal tools … each of them will be different from

the others. That is systematic among all Neanderthal societies.”

Slimak

argues that Homo Sapiens’ disposition for systematisation and standardisation

might have conferred an evolutionary advantage during that period. It wasn’t a

matter of Homo Sapiens wiping out other human species such as Neanderthals.

Rather, their efficient ways may have played an pivotal role in their survival.

To find out

more, listen to the full episode of The Conversation Weekly podcast.

A tooth

that rewrites history? The discovery challenging what we knew about

Neanderthals – podcast. By Mend Mariwany. The Conversation, October 12, 2023.

Neanderthals:

what their extinction could tell us about Homo Sapiens. The Conversation Weekly, October 12, 2023,

They were

long derided as knuckle-draggers, but new discoveries are setting the record

straight. As we rethink the nature of the Neanderthals, we could also learn

something about our own humanity

There’s a

human type we’ve all met: people who find a beleaguered underdog to stick up

for. Sometimes, the underdog is an individual – a runt of a boxer, say.

Sometimes, it is a nation, threatened by a larger neighbour or by the rising

sea. Sometimes, it is a tribe of Indigenous people whose land and health are

imperilled. Sometimes, it is a language down to its last native speakers. The

underdog needn’t be human: there are species of insect, even of fungi, that

have their advocates. But what all these cases all have in common is that the

objects of concern are still alive, if only just. The point of the advocacy is

to prevent their extinction. But what if it’s too late? Can there be advocates

for the extinct?

The past

few years have seen an abundance of works of popular science about a variety of

human beings who once inhabited Eurasia: “Neanderthals”. They died out, it

appears, 40,000 years ago. That number – 40,000 – is as totemic to Neanderthal

specialists as that better known figure, 65 million, is to dinosaur fanciers.

In

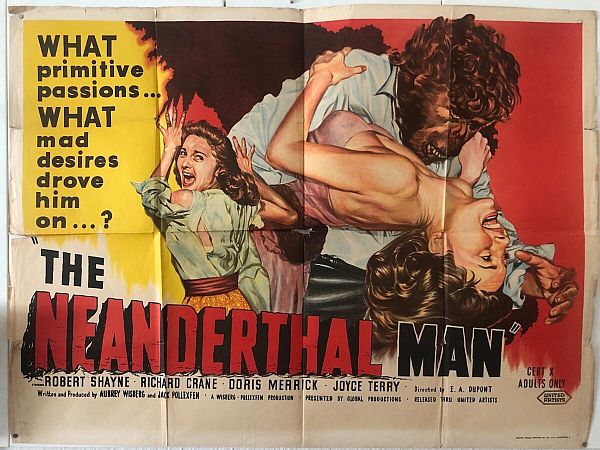

speculative fiction by HG Wells, Philip K Dick, Isaac Asimov, Michael Crichton,

William Golding, and even, improbably, William Shatner, the Neanderthals have

tended to be either brutes or hippies, savages or shamans. A band formed in the

1990s called the Neanderthals was best known for singing crude songs in animal

skins. A critic once used the phrase “Neanderthal TV” to refer to television

for laddish yobs. The fact that we need no explanation for that reference

indicates just how widespread the stereotype is.

Dimitra

Papagianni and Michael A Morse, authors of a fascinating recent survey of

Neanderthal science, The Neanderthals Rediscovered, write in the hope that they

might “restore some dignity to those we replaced”. But what could they mean?

Since there are no Neanderthals around any more, the fight for Neanderthal

dignity risks seeming not merely quixotic but absurd. What does it take to be

indignant on behalf of the dead – no longer here to care much, if they ever

did, for their own dignity?

Some basic

facts about the Neanderthals are now pretty well settled. Of the many species

of hominin, they were the dominant ones from roughly 400,000 years ago until

40,000 years ago. (Hominin is the now orthodox scientific term for any member

of the genus Homo: a group of species that includes all human-like creatures

but excludes, for instance, gorillas.) Their brains were large, their physical

strength considerable. Remains of their bodies have been found scattered widely

across Europe, even as far south as Gibraltar. Why they aren’t still around

remains a vexed question. There are plenty of plausible hypotheses – and

conjectures galore about their psychology and behaviour – but nothing yet

approaching a consensus.

Our

conjectures about the Neanderthals began in 1856, when workers in a limestone

quarry near Düsseldorf discovered a cave full of bones, some of abnormal bulk.

A local naturalist, with uncanny intuition, thought the bones had to be from a

primitive kind of human. He sent them in a chaperoned wooden box to an

anatomist in Bonn, who inspected them and came to the same conclusion. In 1863,

Prof William King, delivering a short paper to the British Association for the

Advancement of Science, argued forcefully that the bones belonged to a creature

for whom we didn’t yet have a name. He went on to propose one: Homo

neanderthalensis.

Why that

name? The valley where the bones were discovered had been a favourite spot for

the wanderings of a 17th-century polymath and nature-lover whose family name

had originally been Neumann, before his ancestors rechristened themselves,

faux-classically, Neander. “Neander” was Greek for “new man”, “Thal” was German

for valley. The Valley of the New Man: “Could there be any more fitting moniker

for the place where we first discovered another kind of human?” asks Rebecca

Wragg Sykes, the author of Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art.

The

discovery of those bones, and their naming in 1863, came at a time when Europe

was coming to terms with the implications of the theories of Charles Darwin. On

the Origin of Species had been published only four years earlier, and it was

becoming harder to deny that the world was older – dramatically older – than we

had supposed.

That name,

Homo neanderthalensis, did two things at once. It proposed that we, proud members

of Homo sapiens, had not always been the only members of our genus. But the

kinship it acknowledged in one breath, it took away from the Neanderthal in the

other. Even if they were human, Neanderthals were humans of a distinct type.

They were like us; indeed, they were rather more like us than the chimpanzees

that we were beginning to acknowledge as our kindred. But they were still

other. Perhaps that was the beginning of the denial of the Neanderthals’

dignity against which their 21st-century champions so bridle.

The fossil

record was already beginning to show us how different a place the world of the

mid-19th century was from the one that the Neanderthals inhabited. There were

animals then that are no longer with us: enormous grazing cattle named aurochs,

straight-tusked elephants, woolly rhinoceros, and the great auk, a giant

penguin-like bird that died out around the time of the discoveries in the

Neander valley.

That world,

barely a blink of an eye in geological time, was, as Wragg Sykes puts it with

sincere excitement, “sparkling with hominins”: Homo antecessor, Homo bodoensis,

Homo heidelbergensis, many of which inhabited the Earth during the very same

periods. There are at least a half dozen now that are widely recognised, and

more seem to be discovered all the time.

The

Neanderthals have been joined, much more recently, for instance, by such

species as Homo floresiensis, irritatingly referred to as “hobbits” after the

discovery of a diminutive skeleton in Indonesia in 2003. In 2010, we got

decisive proof of the Denisovans, another hominin, in Siberia. In the years

since, the hominin ranks have swelled yet further to include Homo naledi (South

Africa) and Homo luzonensis (the Philippines). No one doubts that further

archaeological work, particularly in Africa, will yield yet more hominins. But

the parade of archaic humans all began with the most popular of our fellow

hominins: the Neanderthals.

The most

recent defence of Neanderthal dignity to appear in English is The Naked

Neanderthal by the French paleoanthropologist Ludovic Slimak. He reports

encountering an anthropologist at Stanford who joked, while projecting a slide

of a Neanderthal skull, that “if I got on a plane and saw that the pilot had a

head like that, I’d get off again”. Blunter still was the Russian academic who

kept insisting that the Neanderthals were, simply “different”. Different how?

“Ludovic,” he said, “they have no soul.”

What

exactly is that supposed to mean? Dragged out of the realm of idle metaphor,

the Russian scientist must have been saying that there were psychological

capacities that we, Homo sapiens, have – capacities distinctive of our humanity

– that Homo neanderthalensis lacked. But what were they? That is a scientific

question, to be answered by research, not simply a matter for philosophical

speculation.

It is

beyond doubt now that the knuckle-dragging stereotype of the Neanderthal was

based on a crude mistake. Marcellin Boule, a French pioneer in the subject, has

much to answer for: faced with a well-preserved specimen from a French cave in

1908, he chose to reconstruct, for no obvious scientific reason, its legs and

spine as stooped. A widely circulated illustration of a reconstructed body

depicting the Neanderthal as more ape-like than recognisably human set the tone

for the popular misunderstanding of Neanderthals: inarticulate, slouching,

slow; therefore other; therefore inferior.

Like other

champions of the Neanderthals’ dignity, the evolutionary biologist Clive

Finlayson, author of The Smart Neanderthal and The Humans Who Went Extinct, was

exasperated by the cultural influence of Boule’s scientifically groundless

reconstruction. Armed with better-preserved skulls and fewer assumptions about

the inferiority of the Neanderthals, he was in a position to show why our anatomical

differences from Neanderthals have been overstated. In 2016, he went so far as

to commission a pair of forensic artists to reconstruct full Neanderthal bodies

based on a pair of skulls that had been discovered in Gibraltar, a trove of

Neanderthal remains.

The

reconstructed “Flint” and “Nana”, standing proudly erect, looked as he

expected: uncannily (as we are tempted to say) human. “The exaggerated features

of skull anatomy,” Finlayson writes, “really fade away once you put skin and

flesh to the bone.” The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once wrote that the

best image of the human soul was the human body. Acknowledging the soul – the

dignity – of the Neanderthal might well have to start with acknowledging how

alike their bodies were to ours.

Does the

difference, then, between the Neanderthal and sapiens consist in something to

do with intelligence? But how exactly can we compare our intelligence with that

of beings who aren’t available to sit an IQ test? The answer appears to lie in

working out, from archaeological remains, what they were able to do.

What

immediately catches the eye about the new Neanderthal research is that it has

managed to gather so much from so little. Even in France, where Neanderthal

research thrives, Slimak reminds us that “no archaeological operation has

turned up a new Neanderthal body since the late 1970s”. But the scientists have

learned to make do with the meagre traces the Neanderthals left behind. A bone

and a flint here, a cave there, have proven enough to tell us vastly more than

we knew when the first Neanderthal skeletons appeared in Germany.

A

hypothesis from the 1960s offers a vivid example of the kind of evidence that

can be adduced for Neanderthal intelligence. A team led by the Cambridge

archaeologist Charles McBurney was excavating at a seaside cliff on the Channel

Island of Jersey. An early 20th-century dig had already turned up remnants – in

the form of surviving teeth – of Neanderthal occupation. But at the base of the

cliff, they found an uncommonly large number of bones belonging to mammoth and

rhinoceros. Why were they there?

McBurney’s

field assistant, Katharine Scott, advanced an intriguing hypothesis. Could the

bones be there because the mammoths had tumbled to their deaths from the high

cliff that overlooked the graveyard? Scott pointed to evidence, from surviving

hunter-gatherer societies, of “drive lanes” used to kill large numbers of

bison. The Native American hunters who had been known to practise this kind of

hunting used controlled grass fires to send the animals towards the cliff, and

carefully positioned hunters to keep the animals moving. Had the Neanderthals

used similar hunting techniques?

The old

picture of Neanderthals proposed that they had, at best, a tenuous grasp of how

fire worked – perhaps they were able to use fire when they discovered it, but

were unable to produce it when needed. But this is quite improbable. It is

difficult to sustain the idea that a relatively fur-less species could have

survived in Europe during the glacial periods, when they appear to have

thrived, without a mastery of fire.

And so the

archaeological record indeed suggests. Excavation sites are full of pieces of

flint that show evidence of fire-making. Charcoal remains at these sites

indicate that they were keenest on using resin-rich pine wood as fuel,

suggesting they had decided tastes based on a long history of experimentation.

They may even have learned to use bones to prolong the life of a fire, keeping

them warm while they slept.

The study

of ancient Neanderthal fires is itself a triumph of modern science. The name of

the method – a mouthful – is “fuliginochronology”, a technique by which one

turns a sooty cave into an archive, a veritable guest book of Neanderthal

inhabitation. A fire burning in a cave will leave a mark in the form of

“nano-scale stripes”, which, as Wragg Sykes helpfully explains, are

“essentially tiny stratigraphies written in soot … formed when the fires of

Neanderthals in residence ‘smoked’ the roof and walls, leaving thin soot

films”. As one band of Neanderthals left the cave and another arrived, and

started a new fire, the pattern of soot would produce a sort of unique barcode.

All these fires could hardly be the work of a species with a tenuous grasp of

its workings.

The

Neanderthals, in other words, walked erect, hunted big game and knew how to

control fire: hardly the knuckle-draggers of stereotype.

Last year,

the Nobel prize in physiology or medicine was given to the scientist whose work

has put a number to just how human the Neanderthals were. Svante Pääbo, a

Swedish geneticist, was a pioneer in the study of “paleogenetics”, which began

with the discovery of how DNA might be extracted from a range of sources: old

bones and teeth, naturally, but also from cave sediments. The techniques he and

his colleagues refined have enabled us to know vastly more about the

Neanderthals, their bodies, their habits and their habitats, than their

19th-century discoverers could ever have imagined possible.

Perhaps the

most entertaining thing about Pääbo’s 2014 book, Neanderthal Man: In Search of

Lost Genomes, is how much of it is dedicated to an account of the

palaeogeneticist’s greatest enemy: contamination. Pääbo takes us through the

punctilious quest for absolute cleanliness in the laboratory and for methods

that will help distinguish real Neanderthal DNA from samples contaminated with,

say, the investigator’s own.

Having cut

his teeth on trying to extract DNA from Egyptian mummies in the late 1970s,

Pääbo began to apply his methods to even older bodies. His methods culminated

in a series of triumphs. First, he managed to extract mitochondrial DNA from a

piece of ancient bone allowing him to publish, in 1997, the first Neanderthal

DNA sequences. Thirteen years later came the publication of a full Neanderthal

genome, based on DNA extracted from only three individuals.

The genome offered strong support to what had previously been only a hypothesis: that Homo sapiens and the Neanderthals had had a common ancestor who lived about 600,000 years ago. More significantly, it showed that when early Homo sapiens had walked from their original home in Africa into Eurasia, they had encountered Neanderthals there and interbred with them. The Neanderthals were among the genetic ancestors of modern Europeans and Asians (but not of modern Africans). Eurasians today have between 1.5 and 2.1% of Neanderthal DNA.

Unusually

for a piece of genetics research, Pääbo’s results became the stuff of salacious

tabloid headlines. Playboy magazine interviewed Pääbo about his research,

producing a four-page story titled “Neanderthal Love: Would You Sleep with This

Woman?” The mucky Amazonian Neanderthal woman featured in their illustration

was not designed to be a fantasy object. Meanwhile, men wrote to Pääbo

volunteering to be “examined for Neanderthal heritage” – perhaps seeking a

scientific basis for their stereotypically Neanderthal traits, being “big,

robust, muscular, somewhat crude, and perhaps a little simple”. It was mostly

men who wrote in, though there was the occasional woman convinced her husband

was a Neanderthal.

Other

readers of this research have found Pääbo’s conclusions a source of comfort.

Those wondering what had happened to the Neanderthals 40,000 years ago had long

been tempted by a dark speculation: perhaps we, Homo sapiens, with our superior

weapons and new microbes, had killed them off. But Pääbo’s conclusions give an

otherwise tragic story something of a silver lining: the Neanderthals are still

alive, as alive as the archaic Homo sapiens they interbred with. They live on,

to use an apt cliche, in us, their (very) hybrid heirs. The one vital trace

they have left behind lies in our genes, in the frustrating susceptibility that

modern Eurasians with Neanderthal DNA have to burn in the sun and develop

Crohn’s disease. Perhaps that is a surer way to restore them to dignity than

any other: to see them not as falling prey to our ancestors but as our

ancestors.

Not all

Neanderthal researchers draw such comfort from the DNA studies. Ludovic Slimak

thinks the Neanderthals no more live on “in us” than an extinct wolf lives on

in the poodle who shares sections of the archaic wolf genome. In Slimak’s way

of thinking about the question, the comforting idea that there was no

extinction, only a sort of “dilution”, is tantamount to a failure to see that

Neanderthals were a genuinely “other” kind of humanity, neither better nor

worse, and certainly not “soulless”. “That humanity”, he writes with a brutal

brevity, “is extinct, totally extinct.”

Researchers

anxious to emphasise how much Neanderthals were like us may well be motivated

by the same worthy aspirations of those who thought they could fight racism by

denying the existence of any real difference between human groups. But that,

Slimak proposes, is itself racist. “Racism is the refusal of difference …

Racism is those old images of Plains Indians trussed up in three-piece suits:

just like us.” He sees this as a denial of radical difference, or “alterity” –

a term popular in French philosophy and the social scientific theory inspired

by it.

The old

knuckle-dragging conceptions of Neanderthals certainly don’t do justice to what

the evidence tells us. But they at least did the Neanderthals the courtesy of

allowing them to be different from us. The challenge, Slimak argues, is not to

dignify the Neanderthal by making them, effectively, identical to us, a sort of

“ersatz sapiens”. The challenge is to let them have their dignity while

remaining themselves, a different kind of human, a different kind of humanity.

The

unavoidable talk of “humanity” in these debates forces us to confront a more

fundamental philosophical question of what exactly we take the “human” to mean

in the first place. Agustín Fuentes, an American primatologist, writes that the

deep moral lesson of our new research on the Neanderthals is that we now need

to “reconceptualise the human to recognise our contemporary diversity,

complexity, and distinction as part of a narrative of hundreds of thousands of

years of life, love, death, and art”. The contemporary champions of the

Neanderthals do indeed seem to take the task before us to be one of

recognition, of acknowledgment. But Slimak worries that the language of

“recognition” conceals what is really going on: projection. And projection,

even from the most honourably egalitarian of motives, is still a distortion and

a failure to respect the dignity of difference.

There

appear to be perils in both directions, perils that the analogy with racism

brings out. These debates echo conversations that have haunted us since

Columbus arrived in the New World in 1492. But it is an essential part of our

conversations about colonialism that enough of the colonised – and enough of

their ways of life – have survived for them, or their descendants, to give

their own answers to these questions about similarity and difference. Importantly,

not every person in a colonised nation has given the same answer to these

questions. Maybe we shouldn’t even assume it has a single correct answer.

It is

surprising just how affecting accounts of Neanderthal extinction can be, how

often it moves otherwise sober science writers to unaccustomed pitches of

lyricism. Being a responsible scientist, Wragg Sykes is aware that “ascribing

any level of formal spirituality to Neanderthals would go far beyond the

archaeological evidence”. But she is convinced that we have enough evidence to

be able to say that “they too encountered all of life’s sensory marvels.

Perhaps as photons from a salmon-belly sunset saturated their retinas, or the

groaning song of a mile-high glacier filled their ears, Neanderthals’ brains translated

this to something like awe”. Her “perhaps” registers her awareness that all

this is speculation, maybe even wishful thinking, not (yet) science.

The

Neanderthals cannot speak. As we put our insistent questions to their bones,

their genes and their hearths, we can never be sure that the voice that answers

isn’t just ours, echoing back to us from an ancient cave. But perhaps the

mistake lies in thinking that the question “Are they like us or different?”

presents a real choice. Perhaps the correct answer to that question is, quite

simply, “Yes”. Maybe the best way to accord them their dignity is to treat them

as we treat each other in at least one respect: by allowing them to be

puzzling.

In puzzling

over them, we reveal something of ourselves. Why might some of us care so much

about creatures so long extinct? No doubt part of the answer is that questions

about the Neanderthals serve as proxies for questions about ourselves. The old

fiction writer’s choice between a picture of the Neanderthals as thugs and one

of them as prototypical flower children no doubt reflects anxieties about human

nature that have haunted the last few centuries of our history: are we built

for war or peace?

But is it

really all that eccentric? Is it really odder to want justice for extinct

Neanderthals than it is to want a wrongly convicted friend to be posthumously

exonerated? Thinkers dismissed in their lifetimes as kooks or cranks have been

vindicated several centuries after their martyrdom, by those who rejoiced that

justice had finally been done. It is, if anything, a part of human nature to

resist the idea that our interests die with us: a part of our nature, and a

beautiful one at that. And it makes one wonder: when the civilisations of Homo

sapiens have been reduced to bones and rubble, will our successors on this

planet, digging up our mounds of plastic waste, be as anxious to give us our

due?

Justice for

Neanderthals! What the debate about our long-dead cousins reveals about us. By

Nikhil Krishnan. The Guardian, September 19, 2023.

Explorer

Ludovic Slimak has dedicated decades to unearthing the mystery of our

prehistoric ancestors. Now he has found a missing piece that radically reshapes

our understanding – not just of the Neanderthals but of humanity itself

There’s no

confusing Ludovic Slimak for just another hotel guest. It’s a sweltering Sunday

afternoon in late August and we’ve arranged to meet in the car park of a

guesthouse on the outskirts of Montélimar, southeastern France. The lawn

sprinklers are in full swing; a couple of kids play in the fenced-off poolside

area. Hiding from the heat in my rental car, I’d been concerned we’d struggle

to find each other: Slimak’s email and WhatsApp communication until now have

been at best irregular; the phone signal is patchy in this rural French corner.

As soon as he pulls up in a dust-covered Volkswagen minivan, however, I realise

there’d been no need to worry. Amid the trickle of blissed-out holidaymakers,

Slimak seriously sticks out: he has wild, long hair and an overgrown,

grey-flecked beard; there’s dirt deep beneath his fingernails. It’s 43C,

according to the screen on my dashboard. In shorts and a T-shirt, I’m sweating.

Meanwhile, the man now waving in my direction is dressed in a herringbone

waistcoat, stained linen trousers, denim shirt and Indiana Jones panama hat.

There’s no need for introductions to confirm he’s the man I’m here to visit.

Ludovic Slimak looks a picture-perfect archeological adventurer; a

self-described Neanderthal hunter.

He suggests

we drive in convoy to our final destination, the Grotte Mandrin, a hillside

cave hidden deep in Rhône Valley woodland. “It’s almost impossible to find the

place unless you’ve been there many times,” Slimak explains in fluent English

with a French accent. “And it’s better that way: we don’t want any random

people to – accidentally or otherwise – come across all the treasures we’re

finding.” One of the world’s leading experts on Neanderthals, Slimak has spent

decades travelling across continents in search of insights into this

mysterious, extinct prehistoric species. Just a short drive away, he assures

me, is one the most significant archaeological sites he’s ever spent time

working at. “I started digging there 33 years ago,” he says, “and for the past

20 years I’ve spent a lot of time in this cave, trying to understand

Neanderthals better. It’s here we’re making discoveries that are radically

reshaping our understanding of the history of both Neanderthals and humans,

too.” His book, The Naked Neanderthal, is the result of this research. In 2022,

it was published in France to great acclaim. Now, it’s been translated into

English. That’s why I’m here.

For 15

minutes, we drive in convoy further into the countryside. From a deserted road,

we turn on to an unassuming dirt track. I park up, as instructed, and get into

his VW. We make a bumpy climb a few hundred metres uphill, before we jump out.

I follow him down an overgrown footpath I’d never have noticed. “This cave can

be seen for miles around,” Slimak says, a few steps in front of me. “Locally,

it’s known as ‘The rock of the guide’. The oldest occupation here, we think, is

at least 115,000 years ago. We know there were 500 phases of occupation in this

cave. It’s a hyper-strategic location.”

Sandwiched

between Marseille and Lyon, it feels as if we’re in the middle of nowhere, save

the regular rumble of high-speed trains a hundred or so metres below. “The

national highway and railway lines here represent 70% of European movement

along the north/south axis: a path through the mountains. It’s why this has

historically been very significant.” We turn a final corner. Ahead of us, an

archaeological dig is in full swing. Slimak guides me to the top of the cave

area, where we sit and observe. Seven or eight expert are at work: brushing,

noting, photographing, sorting. His wife – the fellow Neanderthal expert Dr

Laure Metz – is one of those present. Their two sons, nine and six, are back at

the 12th-century castle they rent while on site. Others here are PhD students

and researchers drawn to the dig from all over.

“By all

accounts,” Slimak says, “as a species, Neanderthals are our closest relatives.

And we have parallel histories; common ancestors, I believe, between 300,000

and 500,000 years ago. But then there’s a great divergence.” A separation of

the two creatures. “Homo Sapiens – our ancestors – were mostly in Africa,

although we can see early traces of them in the Near East and Eurasia. There’s

an anomaly, however, with Europe, where we believe Sapiens didn’t really travel

to, home to the largest Neanderthal populations.” The first Neanderthal skull

was discovered in a Belgian cave in 1829; the first bones were found near

Düsseldorf in the 1850s. For millennia, these creatures coexisted on the planet

in different places. “More recently,” Slimak continues, “we have started to

discover there were, in fact, moments where these species met. And here in this

very cave, we’ve made an exciting new discovery.”

At the age

of four, Slimak was asked by his father what he’d like to do when he grew up.

“I said I wanted to make holes in the ground to find old things. I didn’t know

it was a job, until he told me about archaeology.” He’s been at it ever since.

Slimak was born in 1973; his father was a forester. His early years were spent

surrounded by trees, as the family moved across France. “My grandfather lived

in the Pyrenees. He was born in 1918, but really, he was a man from the 19th

century. I spent so much time with him that I also feel like a man from another

era, lost in the modern world.”

By 10,

Slimak had talked his way into various archeological digs he’d come across near

their home. At 14, he was already something of an expert. “By 18, I was working

on a dig here in the Rhône Valley, at a Neanderthal site maybe 70km north.”

These Neanderthals were cannibals. “From then on, I knew I wanted to dedicate

my entire life to these creatures.” At first, university didn’t feel a fit for

this born outdoor explorer. In his 20s, he realised a degree would help him

carve out a career, so enrolled in a course at Aix-Marseille University. To

help pay his way, Slimak learned to play the bagpipes after writing to

Glasgow’s College of Piping, and through busking and playing in Marseille’s

premier late-90s Celtic band earned enough to keep his research afloat. In

2004, he completed his PhD and was soon recruited by Stanford University,

before being hired by France’s prestigious Centre National de la Recherche

Scientifique, where he’s worked ever since.

His Neanderthal hunting has seen him direct digs everywhere from the Horn of Africa to the Arctic Circle. “It’s an exploration,” he says. “On this planet now, there is no longer any exploring to do horizontally in space, but there’s so much to do in time. Neanderthals offer a huge unknown; still, it’s the greatest exploration.”

What

happened to the Neanderthals – their extinction – is one of the greatest

unsolved mysteries. About 40,000 years ago, they vanished. It’s a topic that

has consumed both academic research and fiction. Much effort has been spent trying

to ascertain what led to their demise. But the way Slimak sees it, this might

no longer be the most prescient question. “Normally, archaeologists find that

if Sapiens come into Neanderthal territory, that’s the end of the Neanderthals.

But here we’ve made a unique discovery.” He jumps down in the dig itself,

pointing between various layers of rock and sediment. “We are finding thousands

of things at every level: this is a flint, a flint, a flint, a bone, a flint,

tooth, flint, rib…” The team here can date every bone, tool or rock they

discover while digging. “Neanderthals first occupied this site more than 100,00

years ago. Then, we now know that 54,000 years ago, the first Homo Sapiens

lived here. After that, there were at least five further phases of Neanderthal

inhabitants over a 12,000 year period.”

It sounds

complex, but Slimak is keen to make clear the takeaway is short and simple.

“Finding Homo Sapiens sandwiched between Neanderthal occupants in these caves?

It totally reshapes our understanding of our origins and rewrites what we’ve

believed previously. If both species brushed up against each other over this

long period of time, far more important than what happened to Neanderthals, we

should be asking: what did these two species do together? Did they communicate?

And most importantly, how did they interact? Because Neanderthals experienced

and existed in the world differently to our ancestors. Not just by culture, but

by their very nature.”

He points

to the way prehistoric Homo Sapiens and Neanderthal crafts are vastly

different. “We might not know much about Neanderthals,” he goes on, “but

through what they created, we can see something incredible. When you take Homo

Sapiens tools made of flint, spanning tens of thousands of years, in different

parts of the world, they’re always the same. Standardised. It can’t be

cultural.” There was likely little contact between these different settlements.

“There’s something innate within the behaviour of Homo Sapiens – within our

behaviour – to act and think in a certain way. It’s in our nature.” Neanderthal

crafts, though, don’t share this pattern of standardisation. “Look carefully at

Neanderthal tools and weapons. They’re all unique. Study thousands and you’ll

find each is completely different. My colleagues never realised that. But when

I did, I saw there was a deep divergence in the way Homo Sapiens and

Neanderthals each understand the world.”

Historically,

he believes humanity has had a problem. “To truly understand something, you

need to be able to compare it to something else. But us as Sapiens? We’ve never

had a species to compare ourselves to.” Yes, there are other animals: great

apes, chimps, gorillas. “But we diverged from these creatures maybe 10m years

ago. Of course, compared to a gorilla we have more creativity and skills. It

gives us a certain image of ourselves– one of superiority. But what happens if

we compare ourselves to something far closer – something far more like

humanity, although different, that only disappeared 40,000 years ago?” Imagine,

he suggests, how differently we’d see ourselves if confronted by

hyper-intelligent aliens.

Slimak feels this comparison can and should be made with Neanderthals. “Their tools and weapons are more unique than ours. As creatures, they were far more creative than us. Sapiens are efficient. Collective. We think the same, and don’t like divergence. And I don’t just mean western culture. Go to any Aboriginal society: there are clear rules and customs, and shared styles of clothing. Expectation to act in a certain manner; to follow regulations.” Our ancestors, he says, lived like this instinctively. “You don’t see that with Neanderthals.” By seeing Neanderthals as a reference point against which we can measure ourselves, Slimak reckons humanity is offered a gift: “We have an opportunity to look in a mirror and see ourselves for what we truly are. To help us redefine, which we must do urgently.”

The way he

sees it, this isn’t just an interesting philosophical theory. “Neanderthals

vanished, I think, because of high human efficiency. And this efficiency now

threatens to destroy us, too. That’s what’s killing the planet’s biodiversity.”

For Slimak, The Naked Neanderthal isn’t a history book. “It’s about us in the

present. Urging humanity to see itself for what it is by comparing us to

something else, in the hope of changing the course of our future. Because by

understanding our nature – and the risk this efficiency poses – we can save

ourselves from a similar fate.” Over millennia, humankind has also developed an

advanced, impressive technology and culture, of a type Neanderthals could never

have imagined. “So while there is something dangerous in our nature, as a

collective we can control and reshape it. Understanding this is the key to

humanity’s future. Because if we don’t think carefully, next time it won’t be

Neanderthals that our efficiency destroys, it’ll be humankind itself that’s the

victim.”

‘I feel

like a man from another era’: Neanderthal hunter Ludovic Slimak. By

Michael Segalov. The Guardian, September

10, 2023.

More than

57,000 years have passed since Paleolithic humans stood before the cave wall,

with its soft, chalky rock beckoning like a blank canvas. Their thoughts and

intentions are forever unknowable. But by dragging their fingers across the

rock and pushing them into the cave wall, these creative cave dwellers

deliberately produced enduring lines and dots that would lie hidden beneath the

French countryside for tens of thousands of years.

Now,

scientists have discovered that these arresting patterns are the oldest known

example of Neanderthal cave engravings.

Authors of

a study published Wednesday in PLOS One analyzed, plotted and 3D modeled these

intriguing markings and compared them with other wall markings of all types to

confirm that they are the organized, intentional products of human hands. The

team also dated deep sediment layers that had buried the cave’s opening to

reveal that it was sealed up with the engravings inside at least 57,000 and as

long as 75,000 years ago—long before Homo sapiens arrived in this part of Europe.

This find,

supported by the cave’s array of distinctly Neanderthal stone tools, identifies

Neanderthals as the cave art creators and adds to growing evidence that our

closest relatives were more complex than their dim caveman stereotype might

suggest.

“For a long

time it was thought that Neanderthals were incapable of thinking other than to

ensure their subsistence,” notes archaeologist and study co-author Jean-Claude

Marquet, of the University of Tours, France. “I think this discovery should

lead prehistorians who have doubts about Neanderthal skills to reconsider.”

La

Roche-Cotard is an ancient cave nestled on a wooded hillside above the Loire

River. It was first uncovered in 1846 when quarries were operated in the area

during construction of a railroad line. When it was first excavated in 1912,

the array of prehistoric stone implements and cut-marked and charred bones of

bison, horses and deer within revealed that Paleolithic hunters had frequented

the site many thousands of years earlier.

Scientists

first noted the finger tracings, with their organized appearance, as early as

the 1970s. Beginning in 2016, the authors of the new study diligently plotted

the various distinct panels and created 3D models for comparisons with other

known examples of Paleolithic engravings. They also identified the cave’s many

other wall markings made by the claws of animals, like cave bears, and by metal

or other implements during modern incursions into the cave after 1912. Marquet

says this process helped to show that the engraved panels were created in a

structured and intentional manner. “These panels were not produced in a hurry,

without thought,” he says.

The results

also suggested that the designs were created by human hands, working the soft

chalk wall, a material known as tuffeau, made of fine quartz grains and ancient

mollusk shell fragments. The rock is permeable and covered with a fragile

sandy-clay film.

“When the

tip of a finger comes into contact with this film, a trace is left in the shape

of an impact; when the tip of the finger moves, an elongated digital trace is

left,” Marquet says. He knows this process firsthand. The team reproduced this

method in a nearby cave made of the same type of rock. They marked walls using

tools of bone, wood, antler and stone, as well as with their fingers, which

produced engravings very similar to the ancient examples.

“These

images are not for us, and we do not have the keys to understanding their

meaning, their possibly diverse and multiple functions,” he says.

Scientists know that the cave’s assemblage of discarded stone tools are of the Mousterian technology, sophisticated flake implements that are typically associated with Neanderthals. This suggests the cave was in use exclusively by Neanderthals, who in turn created the carvings on the walls. However, the authors note they can’t establish a direct relationship between those discarded tools and the engravings.

But another

strong line of geological evidence comes from analyzing nearby sediments.

During the Paleolithic, the Loire River, once closer to the hillside, flooded

the cave numerous times and helped to carve out parts of it. Eventually those

floods deposited thick sediments that, aided by erosion from wind and the

hillside above after the river changed course, completely sealed off the cave.

Clear evidence remains showing how layers of sediment were put down over the

years, which would have completely covered the slope and cave entrance to a

depth of more than 30 feet.

This

covering persisted in place until 1846, when material was extracted for the railroad

embankment, exposing the cave entrance. The sediments above and around the cave

entrance, part of the layers that covered it before 19th-century excavations,

were dated by optically stimulated luminescence dating, which can determine how

long it has been since grains of sediment like quartz were exposed to daylight.

A total of 50 sediment samples collected showed the cave was very likely sealed

up at least 57,000 years ago, well before humans lived in this part of France.

Previously, the oldest cave engravings attributed to Neanderthals were an

abstract cross-hatching pattern found in Gorham’s Cave, Gibraltar, and dated to

some 39,000 years ago.

Robert

notes that several lines of evidence—the presence of Neanderthal tools, the

geological evidence and the analysis of the engravings themselves—converge to

demonstrate that the cave walls were adorned by Neanderthals.

“The authors present as convincing a case as

can be made from a site disturbed by early excavations that the animal and

human marks on its walls were left long before the arrival of our own species

in Europe,” says archaeologist Paul Pettitt of Durham University in England,

who wasn’t involved with the research. “Given that the cave’s archaeology is

exclusively indicative of Neanderthals, with no evidence of subsequent Upper

Paleolithic occupation, presumably because the cave was by this time

inaccessible, this provides strong indirect, cumulative evidence that

Neanderthals produced the finger markings.”

Humans from

our family of ancestors began expressing themselves visually a very long time

ago; Homo erectus carved zigzag patterns onto a shell more than half a million

years ago. A series of handprints and footprints, which may have been

deliberately placed by hominin children some 200,000 years ago, has been found

on the Tibetan Plateau.

Examples of

Homo sapiens’ very different style of cave art appear later. A purplish pig

found on the walls of a cave hidden in a highland valley on the Indonesian

island of Sulawesi was painted an estimated 45,500 years ago. If that date is

correct, the Leang Tedongnge cave could be the earliest known work of

figurative art, in which painters recreate real-world objects rather than

producing abstract designs. The collections at Spain’s El Castillo cave and

France’s Chauvet cave, where sophisticated lions and mammoths were painted

perhaps 30,000 to 40,000 years ago, are notable early examples of this complex,

figurative art that is unlike anything Neanderthals are known to have

produced—at least so far.

But that

distinction doesn’t necessarily mean that Neanderthal creations should be

regarded as products of simpler minds or thought processes. Robert believes that

comparisons between Neanderthal and Sapiens traditions aren’t necessary. For

each species, he believes, the appearance of prehistoric carvings and paintings

is less about when people were capable of making them and more about when

social dynamics created a need for them at a specific time—even if those needs

are a mystery to us today.

Oldest

Known Neanderthal Engravings Were Sealed in a Cave for 57,000 Years : The art

was created long before modern humans inhabited France’s Loire Valley. By Brian

Handwerk. Smithsonian Magazine, June 21, 2023.

Neanderthals may have lived in larger groups than previously believed, hunting massive elephants that were up to three times bigger than those of today, according to a new study.

No comments:

Post a Comment