In the third century bc, the Roman nobility became increasingly Greek in their habits, a phenomenon known as “Hellenization,” and those with a particular taste for Greek culture were known as “philhellenic.” Under the rule of the emperor Nero, a notorious tyrant who, incidentally, was said to have twice been in a same-sex union, philhellenism became even more pronounced.

Yet there

was also an ambivalence in this relationship. The Romans, after all, had

conquered the Greeks, and to what extent could you truly want to replicate a

loser’s culture? They filled their homes with Greek sculptures; but they were

looted sculptures, their display as much a mark of subjugation as respect. When

Greek-speaking Romans addressed the Senate, their words were translated into

Latin, as much as a sign of inferiority as to help with comprehension. Even

within the more Hellenistic aristocracy, there were significant figures who saw

Greece as a moral threat, if not a military one. Cato the Elder was one such

figure. Greece, Cato felt, was a degenerate and decadent culture and its

adoption would bring trouble for the Romans, whom he saw as a people of noble

simplicity and strength. Addressing his own child, he said, “I shall speak of

those Greeks in a suitable place, son Marcus, telling what I learned at Athens,

and what benefit it is to look into their books—not to master them. I shall

prove them a most worthless and unteachable race. Believe that this is uttered

by a prophet: whenever that folk impart its literature, it will corrupt

everything.”

This Roman

ambivalence, that the Greeks were both wise and decadent, worthy of study but

worth being wary of, rang down through history and has had a significant impact

on the history of homosexuality. As the classical literature of the Greeks and

Romans was supposedly “rediscovered” by scholars in western Europe in the

Renaissance, many adopted the same prejudices and intellectual arguments that

were being fought almost two millennia earlier. Greek attitudes toward same-sex

relationships were known about and were hard for good Christian academics to

square with their otherwise fulsome admiration of the virtues of classical

Greece. While most Victorian scholars were disgusted by the “unspeakable vice

of the Greeks,” as the uptight Mr. Cornwallis refers to it in E.M. Forster’s

Maurice, those who found their desires drifting in a similar direction found in

Greek culture a heroic example that their sort had indeed always existed, and

began mining Greek literature for heroes and storylines that might serve as a

defense of the unspeakable vice. The works of Greeks like Plutarch and Plato

were used to help imagine a positive model for male and female same-sex

relationships, although neither the Greeks nor the Victorians had quite the

same concept of the “homosexual” that we have today.

For the

Greeks, the concept did not meaningfully exist at all; the social identities we

today understand in the West as a gay man or a bisexual woman, for example,

simply weren’t something that people recognized. Greece was not a single political

entity with a set of laws and customs that everybody followed; different

city-states developed different sexual cultures. Across Greece, sexual activity

between men was common; the important prohibitions were focused not on gender

but status (and hence age).

In Plato’s

Symposium, Aristophanes uses a myth to demonstrate the nature of love,

explaining that lovers are the two reunited components of single souls split in

two by Zeus. This myth of soulmates is not as structured around ideas of

heterosexual compatibility as you might presume. Aristophanes explicitly

mentions same-sex relationships, but the important qualification is that they

are between men of different ages. For Aristophanes, if not necessarily for

Plato, sex between men and boys was not merely tolerable, but noble in itself.

Of such people, Aristophanes says that “while they are boys…they fall in love

with men, they enjoy sex with men and they like to be embraced by men. These

boys are the ones who are outstanding in their childhood and youth, because

they’re inherently more manly than others. I know they sometimes get called

immoral, but that’s wrong: their actions aren’t prompted by immorality but by

courage, manliness, and masculinity. They incline toward their own

characteristics in others.” Worryingly for us, he says such men go on to become

politicians.

What is

fundamental to understand, of course, is that this form of relationship is only

seen as good and honorable between men and teenage boys, while sexual behavior

between men of the same age was taboo. This is an inversion of our own social

norms. Today the defining characteristic of such a relationship to observers

would be the abusive power imbalance. In the same manner, in Greek society it

would also be the age difference that would be regarded as the core

characteristic of the relationship, although in a positive way, and not the

gender roles.

This form

of pederastic relationship was seen to have many qualities; in the Symposium,

Phaedrus suggests that the loyalty between male lovers and their aversion to

being shamed in front of each other by acts of cowardice offered them a unique

advantage in organizing a society, claiming that “the best possible organization

[for a] battalion would be for it to consist of lovers and their boyfriends…A

handful of such men, fighting side by side, could conquer the whole world.” In

fact, such a battalion did exist in the city-state of Thebes. The Sacred Band

of Thebes was a military unit made up of 150 pairs of male lovers and was

regarded as the most elite unit in the Theban army, its soldiers being of

unusual bravery and moral character.

Still, the

acceptance of a certain type of same-sex behavior is littered with qualifications

concerning status. Often, sexual relationships between men involving anything

up the bum were frowned upon, because anal sex is too close to penis-in-vagina

sex. This would make the receptive partner in anal sex something like a woman

or a prostitute, as classical scholar Kenneth Dover writes that in many

circumstances “homosexual anal penetration [was] treated neither as an

expression of love nor as a response to the stimulus of beauty, but as an

aggressive act demonstrating the superiority of the active to the passive

partner,” a drop in status too humiliating to be sanctioned.

To be the

receptive partner in anal sex was regarded as being kinaidos, or effeminate:

there’s no escaping it, bottom-shaming is as old as European civilization itself,

baked into the deep misogyny of patriarchal societies. This prohibition on anal

did not apply to men visiting male sex workers or men having sex with enslaved

males, so long as the man of higher status was the one doing the penetrating—a

good illustration of how, in Greek society, status was the key determinant of

the nature of sexual activity.

The

philhellenic Romans took up many of the same concepts and attitudes toward

homosexuality, but with an important difference. While for the Greeks the

pederastic relationship had a pedagogical and philosophical basis—to ensure the

induction of noble males into the intellectual and political society they were

to dominate—for the Romans the focus was instead on the sensual. Roman culture

was openly celebratory of male dominance and power. There are no European

cultures for whom the hard cock was such a symbol of worship; indeed the Vestal

Virgins, the priestesses of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth, literally

attended to the cult of Fascinus, a deity depicted as a disembodied erect

penis, usually with wings. Their role was to tend to the holy fire at the

center of Rome, from which any Roman citizen could light their own fire. As

such, the fire symbolized the continuance of Rome and the integrity of the

state. That a hard cock was one of the subjects of the Vestal’s adoration is no

coincidence, as the integrity of the male body was a symbol of a free Roman’s

political status. That’s because for a free man, a citizen of Rome, to be the

penetrated partner in a same-sex act was, in some way, a violation of the

integrity of his body. To be a free Roman meant your body could not be

violated. In the words of historian Amy Richlin, “To be penetrated, for a

Roman, was degrading both in a physical sense of invasion, rupture, and

contamination, and in a class sense: the penetrated person’s body was likened

to the body of a slave.” This emphasis on virility and conquest is slightly

different to the Greeks’ obsession with pederasty and pedagogy, but to much the

same ends.

When Marcus

Calpurnius Bibulus accused his enemy and co-consul Julius Caesar of being

“Queen of Bithynia,” the accusation was not that that Caesar was gay but that

he had been fucked in his younger days by Nicomedes IV, the king of Bithynia.

These accusations clearly stuck. Even in Caesar’s moment of triumph, having

crushed the Gauls in the Gallic Wars, a popular rhyme in Rome began “Gallias

Caesar subegit, Caesarem Nicomedes” (Caesar subjugated the Gauls, Nicomedes

subjugated Caesar). As Richlin notes, it seems to be true what the senator

Haterius said, that “unchastity [impudicitia: allowing anal penetration] is a

source of accusation for a freeborn [male], a necessity for a slave, and a duty

for a freed slave.”

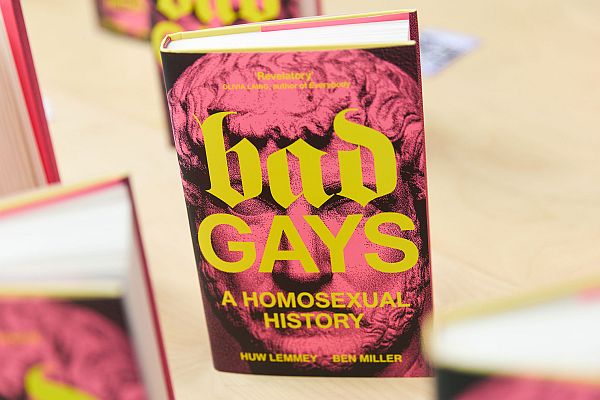

Excerpt

from Bad Gays: A Homosexual History by Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller. Verso Books,

2022.

The Rules

of Attraction : Greek homosexuality and

its influence on ancient Rome. By Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller. Lapham’s Quarterly, June 1, 2022.

The story

of the Kray twins is, like most British stories, one of class, and it begins in

the grinding poverty of 1930s England, still reeling from the effects of the

Great Depression. They were born in 1933 in the heart of London’s East End, a

historically impoverished neighbourhood still suffering from appalling

deprivation.

The Kray

family were part of the busy working-class, multi-ethnic culture. Their mother,

whom they idolised throughout their lives, was descended from Irish and Jewish

migrants. The twins were born in Stean Street, Haggerston, but by the time they

were five or six she’d moved the family closer to her family in Bethnal Green.

Their new home, at 178 Vallance Road, was only half an hour’s walk from their

old home in Hoxton; the area would become the boy’s manor, their spiritual

territory, for the rest of their lives.dc

Charles,

their father, was frequently absent for much of their childhood; working in the

‘rag trade’, the second-hand clothes industry, he frequently travelled for long

stretches buying up goods, and then, when the Second World War began in 1939,

he was a deserter. Their mother Violet took on most of the responsibility of

raising the children and running the home, and by all accounts regarded her

sons as angels, despite Reggie later admitting that ‘we were wicked little

bastards really’.

It is

unsurprising that the lads turned to crime, given both the poverty of the area

and the example they were set. Life in London, particularly in working-class

and immigrant communities, was marked by the presence of organised crime gangs.

They operated on various levels of sophistication, taking part in everything

from pickpocketing rackets to gambling, extortion, prostitution, and blackmail.

Fergus Linnane, in his history London’s Underworld, describes gangs arranged

around both ethnic identities and local loyalties, and spread across most of

the capital in the 1930s and ’40s. There were East End Jewish streets gangs

like ‘The Yiddishers’, the Aldgate Mob, the Bessarabian Tigers, who often took

part in street fights with fascist organisations. In Clerkenwell there was a

mob led by the Italian Charles Sabini that ran lucrative protection rackets at

racecourses, a territory they fought for against the McDonald brothers, who ran

the Elephant and Castle Gang and who went into alliance with the Brummagems, a

Birmingham gang. There were the Titanics in Hoxton, the Hoxton Mob, the Kings

Cross Gang, the Odessians, the West End Boys, and the Whitechapel Mob: an

endless array of gangland groups that emerged, some surviving longer than

others, before being amalgamated, sup- pressed by police, or broken up by

rivals.

Within

working-class London in the interwar period, there was also an independent

homosexual culture of sorts that was distinct from that of the guardsmen and

middle-class johns of Hyde Park and St James’s Park, or the various more

bourgeois gay scenes of Piccadilly, the Haymarket, and Soho. Pubs that were

congregated around the docks and industrial areas often developed a distinct

homosexual or queer clientele, including establishments like the Prospect of

Whitby in Wapping and Charlie Brown’s on West India Dock Road, both little more

than half an hour’s walk from the Kray’s manor. According to the noted

historian of queer life in interwar London Matt Houlbrook, ‘Dock laborers,

sailors from across the world, and families mingled freely with flamboyant

local queans and slumming gentlemen in a protean milieu where queer men and

casual homosexual encounters were an accepted part of everyday life.’

Given the

twin temptations of gang warfare and illicit, criminal sex that existed right

on Ronnie Kray’s own doorstep, it is perhaps surprising that the Kray twins’

first major clash with the law was not a result of either, but rather during

their enlistment into the British army. From the end of the war until 1960,

nearly all British men between the ages of seventeen and twenty-one were

required to serve in the armed forces for eighteen months, and then remain as

reservists for a number of years afterwards. In 1952, the twins were called up.

Their schooling had, says their biographer John Pearson, already been

interrupted by the closure of schools during the Blitz, then by their

evacuation with their mum, to Hadleigh in Suffolk. At fifteen they had left

school altogether, trying to find odd jobs working with their grandfather on

his rags stall, selling firewood, or working in the market, but their real

passion was boxing, which they had took up in a local club when they were just

twelve. Between their fists, pellet guns, and street fighting, they had been in

and out of contact with the police, including getting probation for assault,

but never any more serious punishments. When they turned up at the Tower of

London, conscription papers in hand, in 1952, they were about to be prepared

for a level of discipline they had hitherto never experienced. They did not

fancy it much, and were leaving the barracks when a corporal demanded to know

where they were going. ‘We’re off home to see our mum,’ they replied, and Ron

knocked him out with a punch. After visiting Mum and then going out on the

town, they were arrested the next day back at Vallance Road, where they were

court-martialed and imprisoned for a week.

As soon as they were released from their cells, they went on the run.

For the next two years they played a cat-and-mouse game with the army and

police, finding support while on the run from friends and well-wishers within a

community that had little time for the authorities.

After

assaulting a police officer who came to nick them, they served a short period

in Wormwood Scrubs jail, before being taken back to barracks and escaping

again. Their time in the army was marked by an increasing level of violence and

aggression. In Ron’s words, this was the point at which he ‘started to go a bit

mad’. He regarded himself as having psychic powers, allowing him to read

people’s auras to determine their motives. This, combined with his supposed

shit list of enemies, must have been concerning for people; when he started to

use the nickname ‘The Colonel’, everyone obliged him.

Upon their

release, their criminal career really began. The Regal, a billiard hall on Eric

Street in Mile End, had been experiencing a plague of nightly violence and

vandalism, and the owner was at his wits’ end. The brothers made themselves

available to take it over for a fiver a week; the day they took it over, the

violence stopped. They turned its fortunes round, and the venue became popular

with young people in the area. They began to establish a pattern: Reggie

provided the brains, turning around the business, while Ronnie provided the

brawn, in this instance fighting off the Maltese gangs attempting to shake the

boys down for protection money. Reggie considered going straight, but for Ron,

that was never an option.

Their gang

began to grow, and with it, both their organisation and firepower became more

serious. Ron became obsessed with weapons and firearms: beneath the floorboards

of 178 Vallance Road was a veritable arsenal of weaponry, including a Mauser

rifle and a Luger automatic, plus revolvers, knives, and even cavalry swords.

Their protection racket was organised into two forms of payments. For smaller

premises – pubs, shops, and the like – there was the ‘Nipping List’, whereby

the gang was assured that if they ever needed to drop in for some goods, such

as a crate or two of champagne, it would be given free of charge. Then there

was the ‘Pension List’, where larger establishments like casinos or restaurants

provided a regular fee for their premises to be ‘protected’ by the gang. If

they refused to pay the fee, of course, they soon realised that it was

necessary, as their venues were mysteriously visited by thugs, vandals, or

arsonists.

Quickly,

the gang started to get a serious reputation, demanding respect from all and

sundry while ‘looking after their own’ who were ‘away’ in prison. Despite the

fact they still lived with their mum, they were buying snappy new suits and

getting home visits from the barber, a habit they picked up from watching US

gangster movies. Ronnie was also gaining a reputation as a ‘hard man’. While

there were guns in the London underworld, they were usually for threatening

rather than firing, but Ronnie was known as a man prepared to use them, after

shooting a boxer who threatened one of his protected businesses. The following

year, Ronnie was involved in a gang fight with a group of rivals, the ‘Watney

Streeters’, and one of them broke what was known as the ‘East End code of

silence’ and shopped him; it was 1956 and he was back inside, sentenced to

three years in Wandsworth Prison.

After two

years in Wandsworth, where he continued his criminal activities, Ron was

transferred to a lower security prison on the Isle of Wight. Despite its

relative comfort, he hated it, and began to suffer again from increasingly

severe mental health problems, including paranoid delusions, which he put down

to being triggered by the death of his mother’s sister, Aunt Rose. He had been particularly

close to her, admiring her anti-authoritarian attitude, and her death from

leukaemia devastated him. He was transferred to Long Grove, a psychiatric

hospital, and contrived with his brothers to escape from the institution,

fearing he might be permanently incarcerated. After a few months he handed

himself in, and, astonishingly, was allowed to simply serve the short remainder

of his sentence before being released in 1959.

It was a

fortuitous moment for the boys, to be released just as London was entering a

decade in which society and culture would be radically transformed. They were

twenty-seven, charming and handsome, feared and respected, rich enough to wear

sharp suits and drive fancy cars, and they were looking to make a name for

themselves.

While

Ronnie was inside, Reggie had begun expanding the business empire with

second-hand car dealerships, gambling dens, and a new club, the ‘Double R’, in

tribute to his incarcerated brother.

With Ronnie out, they could do more, and in 1962 established the

‘Kentucky’ club in Mile End.

No sooner

was Ronnie out of jail than Reggie was in, for a bungled attempt at extortion

on behalf of a friend. While he was

locked up in 1960, Ronnie’s worst tendencies for mindless violence,

self-aggrandisement, big spending, and alienating allies all ran wild. He

became aware of the wealth of a notorious slum landlord, Peter Rachman, who had

built up a property empire in Notting Hill by overcharging West Indian

immigrants for substandard housing, enforced by rent collectors and thugs. He

wanted a slice of the pie and approached Rachman at a club, driving him back to

Vallance Road for a cup of tea and some ‘negotiations’. The negotiations were

typical Ronnie: give me £5,000 right now (equivalent to over £100,000 today), or

else. Rachman gave him £250 in cash, and cut him a cheque for another £1,000,

but the cheque bounced. Fearful for his life, and aware that he didn’t want to

open up a rolling financial obligation with Ronnie for ‘protection’, he cut him

a deal, arranging for the twins to buy out a gambling club in swanky

Knightsbridge in West London. They jumped at the chance, and soon were the

proprietors of ‘Esmeralda’s Barn’, their very own West London casino. Although

Ronnie proceeded to run the place into the ground, he revelled in the new-found

status it bought him: he was no longer just an exotic sight for visitors to the

East End, but a player in West End culture. He began hanging around with more

and more important people. Ron particularly liked the powerful politicians, and

the access to dinners at the House of Lords, private members clubs, and sex

with young men that accompanied them.

His

friendships amongst the rich and famous were starting to pay off. In 1963 he was introduced by his

friend, the Labour MP Tom Driberg (who, ever the adventurer, had turned up at

the Kentucky for a drink), to the powerful bisexual Conservative peer Lord

Boothby. Boothby had been dating a young

cat burglar from Shoreditch called Leslie Holt, whom he employed as his driver.

Holt had a flat in an art deco apartment block in Stoke Newington called Cedra

Court; his neighbours were the Kray twins, who each owned a place there.

Boothby

wined and dined Ronnie in his West London clubs, such as White’s; in return,

Ronnie organised ‘sex shows’ and orgies with young men in East

London.Politicians were useful: they were some of the few in society who could

put pressure on the police and prosecutors who were increasingly sniffing

around the Kray’s empire. Driberg, and most likely Boothby too, were invited to

parties at Cedra Court where, in the words of Francis Wheen, ‘rough but

compliant East End lads were served like so many canapés’.

In July of

1964, the friendship hit a crisis. The Sunday Mirror published an exclusive,

claiming that Scotland Yard had begun an investigation into the relationship

between an unnamed peer and an underworld kingpin. Under the headline ‘Peer and

a Gangster: Yard Inquiry’, it claimed to possess photographic evidence of a

lord sat with a mobster who was running London’s largest protection racket.

When a German magazine published Boothby and Kray’s names, Boothby called the

Sunday Mirror’s bluff, outing himself in a letter to the Times as the subject

around whom so many rumours had been flying. What’s more, he denied all

charges, claiming he’d only met Kray three times on business matters.

With his

high-powered lawyers behind him, the Mirror capitulated to Boothby, and settled

with a huge fee and unreserved apology. The fact was that, although he and Kray

were not lovers (they shared tastes in younger men instead), the allegations

were largely true. Both Boothby and Driberg had intervened on behalf of the

Krays behind the scenes in the past, and what’s more, there was a police

investigation into the twins. The Sunday Mirror’s reporter had got his lead

from his informants in Scotland Yard’s criminal investigation department, C11,

that Cedra Court was under observation and an investigation into the Krays’

protection racketeering, fraud, and blackmail was underway.

Yet Driberg

had persuaded the Labour prime minister, Harold Wilson, that Boothby had been

libelled, and deserved his support. In reality, the calculation was political:

it had barely been a year since the Profumo Affair, another sex scandal, had

brought down the Conservative government and brought him to power. But their

majority was slim, and another scandal, this time involving Driberg, would have

been as damaging to him as the Tories. Driberg was such an inveterate and

prolific cocksucker that any cub reporter would have been able to dig up a raft

of men he had blown. Better for everyone, it was decided, if the papers, and

the police, back away. As the Met Commissioner had lied and publicly denied

there was any investigation into the twins, evidence gathered up to that point

had to be discarded.

It was only

ever going to be a temporary reprieve, however. Ronnie was becoming

increasingly out of control. The twins were becoming increasingly concerned

with the activities of their rivals, the Richardson Gang, who controlled

territory in South London. At Christmas 1965, Ronnie heard that one of its

members, George Cornell, a nasty piece of work who worked as a torturer for the

gang, had called him a ‘fat poof’. Trouble was brewing, and in February of 1966

a gang war erupted. There was a series of tit-for-tat attacks, and Ronnie was

in his element, coordinating his troops as ‘The Colonel’ he had always dreamed

of being. In March, a Kray ally, although not a member of the gang, was killed

in a mass shootout at a club in Catford. Major figures in the Richardson Gang

had been shot, and the police had swooped down on it. It looked like victory

for the twins was on hand as their main rivals went to ground.

The next

day, however, Ronnie heard that Cornell was drinking in the Blind Beggar pub,

on their turf. Ronnie holstered his Mauser pistol and got his driver to take

him to the public house opposite Whitechapel Hospital. Entering the bar,

Cornell was said to have greeted him by saying, ‘Well look who’s here.’ Ronnie

put a bullet straight through his head, and left.

Of course,

nobody saw anything, but after his brother Reggie went on to kill Jack ‘the

Hat’ McVitie the following year, the pressure was on. Police detective Leonard

‘Nipper’ Read had been foiled in his investigations once following the Boothby

incident, but now he went after the twins with renewed vigour, and finally

managed to track down the barmaid of the Blind Beggar. She was the crack in the

East End code of silence; given a new identity, she testified against Ronnie,

and alongside his brother he was sentenced to at least thirty years in prison

in 1969.

Ronnie was

eventually, after ten years in prison, moved to the high-security psychiatric

hospital at Broadmoor after being diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. He

would live there for the rest of his life. He never denied his homosexuality,

although sometimes qualified himself as a bisexual. For Ronnie, his

homosexuality was a natural part of his personality, something he was born

with, and as long as he retained his masculine virtues, he was fine with being

seen as a homosexual. What he hated was being regarded as weak; ‘I’m a not a

poof, I’m homosexual,’ he would claim, and loved to identify with icons of

British imperialism, such as Lawrence of Arabia, in whom he saw a model of

masculinity that accommodated violence and bravado as well as desire. Referring

to the imperialist hero Gordon of Khartoum, he said, ‘Gordon was like me,

homosexual, and he met his death like a man. When it’s time for me to go, I

hope I do the same.’ He died in 1995, his ‘reputation’ seemingly intact:

alongside Reggie, he remains something of a folk hero for many, and an unironic

icon of masculinity for many young men.

Extract

from Bad Gays: A Homosexual History by Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller. Verso Books,

2022

The story

of Ronnie Kray’s queer machismo. By Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller. Huck, June 10,

2022.

Bad Gays is a podcast series and book hosted and written by by Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller about evil and complicated queers throughout history. Miller and Lemmey will be in conversation at Brighton’s Coast is Queer festival on Saturday 8 October. For PinkNews, they explain why the history of homosexuality is much more complex than we like to think.

When it

comes LGBTQ+ political trailblazers, we are spoilt for choice.

There’s

Harvey Milk, the San Francisco supervisor who fought against homophobic

discrimination in alliance with other marginalised people. Or there’s the queer

Black feminist Angela Davis, a brilliant abolitionist activist and professor.

The

internationally-minded might choose Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir, the former

Icelandic prime minister and the world’s first openly gay head of government.

Yet the

person who could be provocatively described as the world’s first openly

homosexual politician was far from a hero. He was Ernst Röhm, an early member

of the Nazi Party and the leader of Hitler’s brown-shirted, street-fighting

fascist militia, the SA.

Proud of a

social and sexual identity that rejected women as unsuitable partners for a

masculinist warrior caste, either on the battlefield or in the bedroom, Röhm

saw, as his biographer Eleanor Hancock has demonstrated, little contradiction

between his political ideals and his same-sex desire. While that desire did not

stop his ascent through the Nazi ranks, it did provide the pretext for his

assassination in Hitler’s purge of the SA in 1934.

To our

contemporary ears, such a life seems counterintuitive, even bizarre. While

academic and activist conversations have long since moved on, most mainstream

gay rights advocates – and most LGBTQ+ people – subscribe to the idea that

homosexuals represent a stable and eternal minority, a minority that was

eternally oppressed and then, in the 20th century, found its way to civil

equality.

It’s a

comforting fiction. Faced with discrimination and stereotyping, people

classified as homosexual – the category has only existed since the mid-1860s –

have excavated the past to find heroes and icons.

Yet an

equally important historical and activist project (think theorist Michel

Foucault, writer, sex worker, and labor activist Amber Hollibaugh, and the late

and dearly departed activist historian Jeffrey Escoffier) has countered this

search for heroes with an attempt to understand homosexuality as what it is:

one specific and contingent structure for same-sex desire and love.

Like all

good history, this approach is both more true and less boring. Gay and lesbian

people aren’t “born this way” – a myth that understands homosexuality as,

fundamentally, an affliction – and we don’t act in pre-set ways, heroic or

abject, cowering or courageous. Our lives and stories are stranger and more

powerful than that. But to tell that history, we need to discuss the bad gays

like Ernst Röhm just as much as the good ones. We need to talk about gay

villains.

After all,

what is the story of Oscar Wilde, the literary star and aesthete whose trial

and spectacular downfall gave the British public one of their first clear

images of what an openly gay man was, without the complementary story of his

impetuous young lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, better known as Bosie? It was

Bosie’s licentious, libertine lifestyle that first attracted Wilde to him, a

lifestyle borne of his adherence to the idea of a new sexual type emerging in Europe

at the time, the ‘uranian.’

The

uranian, to simplify, was thought of as a third sex, a woman’s soul contained

within a man’s body (or vice versa). Today few would regard this as the

accurate description of a homosexual man or woman, yet these were the early

roots of a self-consciously gay sexual identity – roots that demonstrate

conclusively the ahistorical, cynical foolishness of present-day gays and

lesbians who would abandon trans people based on the phobic lie that it is

possible to separate the histories of same-sex love and of gender identity.

Uranians

(unlike many other early proto-gay and proto-trans ways of being) emerged from

a middle and upper-class, white European cultural milieu. The phrase “the love

that dare not speak its name” was first coined in Bosie’s poetry, and Wilde’s

fate was sealed by the conflict between Bosie’s ideals and those of his

violent, aristocratic conservative father, the 9th Marquess of Queensbury, whom

Bosie encouraged Wilde to sue for libelling him as a sodomite.

The

problem, of course, was that Wilde was a sodomite. A sentence of hard labour

broke Wilde’s body, and Bosie’s callous cruelty broke his spirit, drawing to a

premature end one of Ireland’s greatest literary talents.

Bosie moved

on to a career peddling vile antisemitic conspiracy theories and died in the

final days of World War II, unmourned. Yet his life is as illuminating, if not

more so, of the formation of homosexual identity as Wilde’s.

Some bad gays’ lives were more complicated than pure evil. The Irish anti-colonial activist and journalist Roger Casement travelled through the Congo keeping two sets of diaries. The first set documented the atrocities he witnessed in what the historian Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja has demonstrated to have been near-genocidal, if very profitable, Belgian colonial rule.

In his

second set of diaries, Casement documented each of his sexual encounters in the

colonies, including precise annotations of each man’s anatomical attributes and

how much he paid for the encounter.

These trips

were taken on behalf of a British colonial regime that commissioned Casement’s

reports in an attempt to falsely depict itself as a kinder, gentler colonizer.

After Casement came to a deeper understanding of Britain’s own colonial

violence and attempted to run guns to the Irish nationalist Easter Rising, the

British authorities didn’t hesitate to turn on him: He was sentenced to death

for treason.

A story

like this, with its nearly infinite ethical complexities, can tell us so much

more about race, power, empire and gay identity than simple sanitized stories

about gay heroism.

Even LGBTQ+

people’s desire to look to the Classical past for heroes will often turn up

morally complex figures, and figures whose sexualities do not correspond to

homosexuality as we understand it to exist today.

The Roman emperor Hadrian lived in a world whose sexual regime was governed by ideas about status and hierarchy in which same-sex contact was acceptable so long as the higher-status man penetrated the lower-status one.

Married to

a woman, Sabina, for his whole adult life, he conducted a disastrous love

affair with his younger friend Antinous which ended in Antinous’ possibly

ritual drowning on a Nile river cruise, and subsequent deification. But this

sexual regime had its own taboos and regulations: Julius Caesar was mocked not

for engaging in same-sex activity, but for having sex with men of similar

status, and more shameful, for having been the receptive partner.

A closer

look at the nature of same-sex love in the society in which Hadrian lived

complicates the idea of an unchanging thread of homosexuality that passes

through history, sometimes suppressed and sometimes celebrated but always

looking and feeling the same.

Remembering

the bad gays of history in their full detail doesn’t redeem them, nor need it

fuel popular bigotries and conspiracy theories.

While

homophobes and transphobes demand we simplify our understanding of sexuality

and gender down to a few inherited and uncritical assumptions, an LGBTQ+

movement based on justice and solidarity is surely strong enough to realise

that human beings, in their loves, hatreds and desires are more complicated

than that. Our rich, varied and sometimes horrible history certainly suggests

so.

If we

understand being gay as neither an affliction nor a blessing but simply a way

of being that, like every other social institution, is shaped by the structures

of race and class and gender, then all of us, gay and straight, can see the

world more clearly – and fight for a better one. The villains of the past,

strangely, might point the way to a just future.

We need to

discuss ‘bad gays’ like Nazi monster Ernst Röhm just as much as the good ones.

By Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller. Pink News,

October 6, 2022.

Authors Huw

Lemmey and Ben Miller approach LGTBQ+ history from a unique angle on their

"Bad Gays" podcast, which is, as the title suggests, not necessarily

about the shining figures of virtue that we've all heard about, be they Enigma

codebreaker (and victim of government persecution) Alan Turing or Harvey Milk,

the martyr for freedom and equality whose message was all about giving hope to

the next gay generation.

Lemmey and

Miller focus instead on more complicated historical figures. In their

recently-published book, also titled "Bad Gays," the two adopt fairly

narrow criteria for which historical figures to include — with one exception,

they are all gay men, for instance. Even so, they document a surprising breadth

of badness that ranges from "somewhat naughty" to "downright

evil," including no less a notorious figure than Ernst Röhm, the out Nazi

who paid with his life when Hitler betrayed him (and a lot of others) on the

"Night of Long Knives."

Röhm is an

extreme example, along with Roy Cohn and J. Edgar Hoover; most of the men the

book talks about fall into a middle ground, from the paradoxical British and

Scottish monarch (King James VI, who commissioned the version of the Bible that

claims gay sex is an "abomination," but who had male lovers himself);

to the blindly colonial (such as T.E. Lawrence, aka Lawrence of Arabia), to

those who were "bad" only because they defied the powers of their

time. The book is a compendium of a much richer and fuller gay history than

much of what we've seen before.

And above telling us the stories of individual gay men throughout history, the book challenges our modern notions of homosexuality as an identity, making a compelling argument for how and why the "gay" of today is different from that of yesteryear, and how those conceptions are profoundly, inextricably bound up with colonialism, money, and class.

"Bad

Gays" is an entertainingly erudite illumination of a history that bad

straights like Ron DeSantis and his ilk will never allow to be taught in

schools — which is why it's all but required reading for anyone who wants to be

deeply informed about who we are and where we came from.

EDGE had

the pleasure of chatting with Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller and learning about the

strange and marvelous history of "Bad Gays."

EDGE: The

book is based on your podcast. What was the seed of inspiration that led to the

podcast?

Huw Lemmey:

We had this idea for a podcast that came about through research for other

things I was writing. These fascinating figures kept coming up who were gay

men, and I realized that they weren't being thought about within the context of

their sexuality, even though quite often their sexuality was quite influential

on their lives. I was talking to Ben about it and saying, "Why is queer

history so often given to us as a positive history of heroes, of reclaiming the

stories?" Ben explained to me how early gay history emerged as a response

to the stigmatization of gay people in order to say, "We aren't just these

people living in the shadows. We actually come from this long line of

influential, important people who've changed the world."

I said to

Ben, "Well, I'd like to do a podcast where we discuss the anti-heroes or

the villains, what stories their lives might tell us also about how

homosexuality came to be, and hopefully it'll be entertaining along the way.

Would you be interested in joining me?"

The book

came out of the podcast because we kept having similar stories emerging, or

stories that had similar contexts around race or similar issues. Probably the

most important one of those is the relationship between homosexuality and

colonialism. We were quite careful about selecting exactly who we were going to

feature in the book, in order to tell the story that was a bit deeper, and that

dealt with some of those issues in a way that hadn't really been dealt with

before — not in a popular history book, at least.

Ben Miller:

One of the great things about doing the show is the opportunity to every week

go to some really different place. So, we'll go to 15th-century Japan, and then

we'll go to Victorian London, and then we'll go to some eccentric British oil

heir taking over an island in the Bahamas and ruling it with their life

partner, who is a foot-tall leather doll named Lord Tod Wadley. I'm not making

that up.

[Editor's

Note: Indeed, he is not; The story of "Joe" Carstairs, who was

seemingly either trans or non-binary, is recounted in the biography "The

Queen of Whale Cay," by Kate Summerscale.]

The book

format pushed us towards a more in-depth kind of storytelling. We wanted to

have all of the different profiles in the book add up to a bigger and more

comprehensive argument about how we think a more interesting, and a truer,

conversation about queer history could look.

EDGE: You

make the case that our current notions around how we think about homosexuality

in general is deeply connected to forces in history like colonialism,

capitalism, the exploitation of workers, and the manipulation of law and

society by the ruling class. You must have taken note of how Singapore recently

shed a holdover of British colonialism and decriminalized sex between men.

Huw Lemmey:

I think I'm right in saying that the single the law in a Singaporean penal code

is a direct copy and paste of the British colonial codes. It's quite

interesting, doing some of this research. The law [against sex between men] in

Jamaica and the law in Singapore are worded exactly the same. That's no

coincidence.

EDGE: It

seems from your argument that how we think about homosexuality today is a

social construct resulting in large part from those historical forces. But at

the very most elemental level, some people are sexually and romantically

attracted to others of the same gender, and some people feel that their innate

genders is different from what others assume it to be by looking at them — or

they don't feel they fit into a binary model of gender at all.

Ben Miller:

So here's where I'm going to step in and do some conceptual clarification. When

we talk about our operating definitions of homosexuality and gender, and when

we make an argument and show how they evolved, and what we think the problems

with them are, and then [ask] what would happen if we abandoned it and did

something else instead, we're also clear to say that we're standing on top of

this identity. We are writing from within this identity. We are, you and I,

both in this and implicated by it.

When we're

saying that things are new, what we are not saying is that the impulses that

those social institutions codify are new. They are not. When we talk about

someone like Hadrian, we're talking about someone who clearly has both sexual and

romantic attraction to other men. Same with Frederick the Great, same with a

bunch of the other people that we talk about. But if you go into, "What

does that actually mean to Hadrian, in Hadrian's time? What does the practice

of sex between men look like?," it is not this idea we have now, where

there is a stable minority of same-sex attracted men who are gender normative,

and who, over the course of their life, may play both the penetrative and

penetrated role. Instead, what you have is a situation where patriarchs of

families are married to women, and also topping twinks. And now we don't call

that being gay; we call that being in the Republican party. [Laughter]

Huw Lemmey:

Today, how we organize those desires is like a social identity. In the last 50

or 60 years, you've seen a huge change from what "gay" would have

meant, say, at the time of Stonewall, when there were people included within

the umbrella of "gay" who today would be defined, and perhaps define

themselves, into different identities. The reason why those people perhaps

didn't feel included within [that umbrella identity] is partly down to the way

it was formed in the first place.

EDGE: Your

chapter on "The Bad Gays of the Weimar Republic" strikes

disconcertingly familiar chords that resonate alarmingly with current affairs.

Is there hope we might avoid repeating the way Weimar Germany collapsed into

fascism?

Ben Miller:

Yes, there is hope. And I think that's precisely because these forms are always

changing, and because we are always faced with the task of making something

from what we have been given; trying to make lives and make politics that are

ethical, and that are up to the task of changing the world.

EDGE: Do you foresee follow-up books? "Bad Lesbians," or maybe "Bad Gays, Part II?"

Ben Miller:

I think we foresee a lot more of the show, and if people are interested in bad

lesbians and [other] kinds of things, I really do recommend they [listen to]

the show, because it's not just us talking. We invite a lot of people on to

talk about folks they've researched, and that's a really great kind of bonus

for people, that they don't only have to listen to our voices.

In terms of

other books, we'd have to see. I think what made doing this book meaningful and

important was that we thought that this was a story that we were both burning

to tell, and we thought we could tell it well through this framework. Our

thesis is about colonialism and capital and white male homosexual identity —

the white gay man, how he happened, and why it was a mistake is our is our

framing there. We would need to find another organizing principle that made

sense for a second book for us. I do hope that more people start making popular

media about queer history that is reflective of the smart and interesting

conversations that people are having.

Podcasters

Huw Lemmey & Ben Miller Want You To Know the 'Bad Gays'. By Kilian Melloy.

EDGE, January 8, 2023.

Along with

the historic rate of youth LGBTQ+ identification—20.8 percent of Gen Z

respondents answered a Gallup poll affirmatively last year—a remarkable feature

of the contemporary sexual order is the ready availability of popular histories

of queer activism. This arms present conflicts over gender and sexuality with a

sense of how long the fight has been prepared for, and a lineage of dignified

predecessors in struggle to join. But in this historical narrative, the reality

of these ancestors as engaged political actors can be paradoxically easy to

miss. Personal queer history is often confirmed but not challenged by

historical queer persons, who can remain sealed behind this narrative even if

they are still alive.

Huw Lemmey

and Ben Miller’s popular podcast and now book, Bad Gays, takes a slightly arch

approach to deliver a corrective to the dominant narrative of heroic queers perfecting

liberal society. In each of their carefully researched chapters, they adopt one

or more of the titular “bad gays” as an opportunity for a complicated

discussion of certain unsavory characters who nevertheless left decisive marks

on the shape of contemporary sexual and gender identities, or whose experience

provides a useful reference point against which to measure their change.

The “bad

gay” is a venerable slur, gleefully deployed against Nazis or other figures of

evil to distance their acts from implicitly straight innocence by the further

charge of sexual deviance or, better, self-hatred. And in fact Ernst Röhm, J.

Edgar Hoover, and Roy Cohn all make the appalling roster here, though Lemmey

and Miller’s point is not to blame the 20th century on closet cases but to

enrich queer politics with a supple enough historical sense to move

inventively, without naturalizing the moral categories it wants to explode.

Advancing

briskly from Hadrian to Lawrence of Arabia, and Yukio Mishima to Margaret Mead,

their negative canon illuminates the long prehistory of the contradictory

situation we all find ourselves in now, with a partially liberated sexual and

gender order that preserves archaic violence alongside innovative forms of

freedom. Recently, I corresponded with Lemmey and Miller to learn more about

their approach to what they call “homosexual history.”

MAX FOX:

One of the bolder premises in the book is your claim that the project of

homosexuality was a failure. What do you mean by that?

BEN MILLER:

The quote is that the book “investigates the failure of white male

homosexuality as an identity and a political project.” White male homosexuality

is one of the most successful political projects of the 20th century in terms

of its ability to achieve civil rights and state recognition in record time.

Huw and I are both white male homosexuals; we stand on top of that identity and

are implicated in its successes, failures, exclusions, and the violence it’s

done to others on its long march through the institutions. Our book is a

counterhistory of that march through the institutions, one which focuses on the

various poisons baked into the cake of that identitarian and political project

from the beginning, by way of trying to dream a wilder, more inclusive, more

powerful, more fun, and more interesting future for everyone.

What are the poisons baked into the cake? Well, we identify some primary themes that run through the stories, all of which are common parlance in scholarly and activist communities but less well-known in queer public history. One is the degree to which the white gay man benefited from and evolved out of European colonization of the Global South—ideas about colonized people circulated in metropolitan capitals and served as the foundation for gay activists’ claims about themselves, their histories, and their identities.

Meanwhile,

those gays were often complicit in the colonial project—some, like Cecil

Rhodes, were leaders of that project—and too many white gay movements have

ignored or actively oppressed queer-of-color organizing. Another is the white

gay man’s rejection of femininity and gender nonconformity: In trying to be a

“real man,” he’s often thrown allies under the bus. In telling these stories,

we hope to give people tools with which to think critically about our past,

understand how we are implicated in it, and dream the future forward.

MF: The

gambit of thinking about “bad gays” is a way to move against a certain figure

of the homosexual as an eternally and piously oppressed identity, which was

central to bids for rights on the basis of its respectability. But in other

ways, the bad figure seems to have been uncritically reactivated recently—it’s

swirling around the panic over “grooming” and threatened to merge with the

response to monkeypox. Does your historical investigation give you a better way

of responding to this slur than respectability politics would?

HUW LEMMEY:

I think orienting one’s sexual politics around an appeal to a third party is a

strange compulsion that doesn’t really work for anyone. It’s a continuation of

that same imperative that’s leveled upon the left in general to dilute its

goals and ideas to appeal to a mythical “normal” voter: The costs outpace the

rewards, simultaneously invalidating our own desires while casting the “norm”

as natural. So in terms of gay politics, there may be ever more visibility for

gay people, but the depth of that representation is shallow; the idea of what sexuality

could mean, how it could challenge and strengthen us, is limited. At the same

time, that limits our ability to fight back when the “norm” shifts against us.

The response to monkeypox is a great example: When outbreaks started occurring

in major European and US cities, it was gay men who were disproportionately

affected. To me, that was unsurprising; although there are lots of ways to be

gay, there is a different sex culture among many gay men in cities. Yet when

those same groups started advocating for access to emergency health care and

vaccines, in addition to the usual government foot-dragging and resistance, we

also saw a pushback from other LGBTQ people claiming that targeting gay men for

vaccine programs was “stigmatizing” homosexuality and would label monkeypox as

a “gay plague.” There were even a large number of accusations that targeting a

vulnerable demographic for increased health care was a rerun of the

stigmatization we saw during the early AIDS crisis—a terrible misreading of

history.

I think

part of this problem emerges from the reluctance or inability to have honest

and frank conversations between ourselves as gay people. Gay life has broken

through into mainstream culture, but largely for a sympathetic straight

audience, and discussions tend to be oriented outwards. As a result, there’s

less space for us to talk between ourselves and represent ourselves to

ourselves. So when we started Bad Gays, other gays were our audience. We wanted

to have conversations that didn’t shy away from those complex conversations

about the historical figures and identities that have shaped our contemporary

identity. I think that’s an important political project; when other gays accuse

us, as they have, of “airing our dirty linen in public,” I’m OK with that,

because it means we’ve given up censoring our conversations for the sake of

straight people.

MF: You

argue against an idea of linear progression for thinking about this history,

though this a cherished concept for people who want to warn against “going

backwards.” What is a more useful way to think about this?

BM: History

isn’t an arc that bends in any particular direction; it’s poems about ghosts,

and sometimes they rhyme, but they don’t always make sense. Imagining gay

history as a seamless evolution of ever-increasing rights and visibility is

profoundly historically inaccurate, and also boring and reactionary. It led,

for example, to the popularization of triumph narratives about civil rights

achievements in the mid-2010s that helped continue demobilizing gay movements;

now, only a few years later, new far-right moral panics about “groomers” and

trans kids demonstrate how short-sighted that demobilization was. Once you

realize the value of liberation can go up or down, you actually appreciate the

strategic and ethical need to align the liberation of sexual and gender

minorities with a universalist politics.

HL: I think

it flatters everyone to suggest that we are smarter, kinder, and more just than

those who came before us. Sadly, it isn’t true; history suggests that the gay

identity is formed from a series of moral panics. These moral panics

counterintuitively communicate to people the presence and availability of

deviating from the restrictive norms and finding solidarity in gay life. It’s

useful and important to be aware of the fact that those who tolerate you now,

or even think of themselves as “allies,” may very well be complicit in the next

reactionary wave. The emphasis must surely be on building a wider form of

political solidarity to help as many of us as possible survive.

MF: I was

struck by this question you pose in your introduction: “Why do configurations

of identity and desire that seem to have expired continue to hold such power

over so many people?” Do you think you’ve come to some understanding through

writing this book?

BM: Michel

Foucault was joking about the sexual liberation movements believing that

“tomorrow, sex will be good again” in the 1970s! I think we get through it by

going through it and actually addressing and engaging with it, not simply

rejecting it.

HL: None of

us are immune to the idea that things were simpler in the past, that we just

missed a golden age. Not just the past—I think we also look sideways at how

others organize their desire and wish we could have some of that. But I think,

in terms of desire, there’s also a feeling that we want to better understand

the modes of identity that we’ve inherited. My conclusion from writing the book

is that much of the deep sexual anxiety we’re seeing in Europe and the US at the

moment, from gay as well as straight people, comes from an epochal shift within

our current sex-gender system that is very confusing for people who have come

to think of their sexuality as a transhistorical truth, something unchanged

through the centuries that has only, in the past century, been allowed to

flower. That change looks like a threat, but history suggests it’s just the

latest turn in an ever-shifting fluctuation of identities.

MF: I’ve seen people argue that because the terms and categories change, the historical basis for a coalitional identity is a romantic fabrication. You say that coalition is the only thing that’s ever worked. Why is that?

BM: Well,

lesbians were targeted by the Nazis, as were trans people, and Sylvia Rivera

and Marsha P. Johnson sure did think of themselves as women and as people whose

social identities were profoundly shaped by gender transgression, even if they

lived some of their lives at a moment when identity categories were sliced

somewhat differently and a word like “gay” was more capacious than it is now.

Post-Foucauldian gay and lesbian history has learned some of the wrong lessons:

As Helmut Puff wrote a few years back, “A generation of researchers translated

a somewhat paradoxical [argument], especially in the standard English

translation, into a road map on how to do research on the history of

homosexuality.” If our intervention into public history is to urge people to be

more precise and specific and understand queer history in more complicated

ways, then I think we’re also thumbing our nose a bit at certain strands of

academic history that get bogged down in terminological debates that can

often—as in the case of the gay men who object to the remembrance of the Nazi

persecution of trans people and lesbians, or the gay men who insist that Marsha

and Sylvia weren’t actually meaningfully trans––become reactionary.

MF: Does

this history give us a way to think about the contemporary fascist mobilization

around trans people, or does that come out of a different historical sequence?

BM: The

history of fascist mobilization against trans people is extremely present in

our book, most prominently in the chapter about Weimar history. For me it is

impossible to look at the ways in which sex and gender deviance were constructed

as threats to the nation and not see profoundly disturbing correspondences with

today’s transphobic mobilizations. The cover of Abigail Shrier’s book,

Irreversible Damage, with the little white girl’s reproductive organs

obliterated by a black hole—what she calls “the transgender craze seducing our

daughters”—could be a Nazi propaganda poster.

HL: History

doesn’t repeat; it rhymes, to paraphrase Twain. The current moment of fascist

mobilization is not the same as that in the ’30s, but there is plenty to learn

from that period about the anxieties and hatreds that were fed, and fed upon,

by the Nazis. Perhaps most important would be the anxieties around collapsing

masculinity, blurring traditional gender roles, and the fear that the state is

becoming weak. It’s telling that, despite the US spending more than the next

eight largest countries combined on its own military, there is such a willing

audience for the idea that LGBTQ people are weakening US defense that the

traditional transphobic joke has as its punch line an attack helicopter; that

upon the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there was a sudden spike in conversations

about the tolerance of LGBTQ people in Europe having strengthened Putin’s

resolve; and so on. These fears of sexual and moral degradation, military and

masculine weakness, and the penetrability of a nation’s sovereignty—all of them

have precedent in interwar Europe, as do the hate campaigns that are springing

from them.

In recent

decades, the idea that homosexual tolerance, and indeed homosexuality, was the

logical consequence of the Western liberal project has become commonplace,

utilized to conscript gay rights into that project, to exclude LGBTQ Muslims,

and to demonize brown people in general. Any gay person who has argued against

Western interventionist policy, or for the rights of the Palestinian people,

will recognize this—as well as the inevitable wide-eyed, salivating, and

gleeful response from a straight person that “they’d throw you off the top of a

building over there.” Not only has that project demonized others, but it has

helped boost this nationalist obsession with sexual moral hygiene and the

integrity of borders. These are chickens coming home to roost; history proves

that even the most masculinist, fascist, flag-waving gays rarely survive what

follows.

MF: The

chapter on Weimar Germany is especially interesting, since that time and place

loom so large in liberal minds as a figure of sexual liberation inviting

reactionary backlash. This ends up agreeing with preserving an idea of sexual

freedom as decadence. What would you say your investigation of the Weimar gays

actually teaches us?

BM:

Historian Laurie Marhoefer’s argument, [in Sex and the Weimar Republic]

proposes that Weimar Berlin’s sexual liberation movement was much like the

movements of the 1960s and 1970s in the English-speaking world: They both had

multiple ideological and intellectual strands, were complex and often

contradictory, and had central elements that were willing to accept a more

“scientific” and progressive understanding of sexual and gender difference in

exchange for sharpened penalties against people understood to be particularly

deviant, like sex workers. This does not, of course, mean that Nazi backlash

against gay and trans visibility wasn’t a huge part of their project of murder

and repression. I think this way of looking at Weimar helps us get closer to an

understanding of the similarities between that moment and our own.

MF: The

current public understanding of homosexuality is one that you trace as emerging

from a series of concessions to power, punctuated by moments of revolt and

opportunities for alliance. What would you say that people interested in moving

beyond this project should be looking for?

HL: Most

fundamentally, that same-sex desire is not an identity category strong enough

to ensure solidarity in and of itself, and that a wider coalition is necessary.

At the same time, coalitions cannot demand that one party lives like the other

party, or that one party bends to meet the demands of the other. We are all

different people; our experiences even within that identity category vary

vastly, inflected by our other identities. Lastly, that difference perseveres

and survives.

BM: We end

the book with a dance through some moments when queer people and movements

approached, however fleetingly, a lived politics of alliance capable of making

transformative change. Some of these moments––like the Combahee River

Collective and its movement-defining statement––are well-known, others of them

less so. One of my favorite stories in that conclusion comes from Allan Bérubé

and Aaron Lecklider’s research into the pro-gay, anti-racist Communist Marine

Cooks and Stewards union that worked on the Pacific Merchant Marine fleet in

the 1930s. They had signs saying: “No Red-Baiting, No Race-Baiting, No

Queen-Baiting.” Someone threatened to beat up a member for being a queen, and

he beat him bloody with a soup ladle and said, essentially, that a union queen

was willing to be mean to defend her comrades. We should all aspire to that.

MF: Your

last profile is of Pim Fortuyn, who synthesizes some of the worst strains of

masculinism with the liberal appeals to tolerance that preserve the idea of

homosexuality as bad but whiteness as good because it can withstand it. You

draw parallels with Milo Yiannopolous, Andrew Sullivan—maybe we would include

Glenn Greenwald in a couple of years. Are gays like this the future, or can we

defeat them?

BM: This is the more pessimistic part of our conclusion: that the center-right acceptance of certain elements of the liberal rights consensus about gays and lesbians will lead to more Fortuyns and Sullivans. Indeed, to the extent that Sullivan helped theorize that rights consensus with his arguments for demobilization after AIDS and marriage equality as a dignifying signature issue, this was intentional. I think we can defeat them, but I also fear they will grow in number.

HL: While

it was possible, even personally profitable, for certain types of gay

men—especially men like us, white cis gay men—to adopt an approach that

valorized marriage, the military, whiteness, and the nation-state a decade ago,

it’s harder to valorize what comes next: not just the accusation of being

groomers, of perversion and subversion, but also the implication among former

allies that there’s at least some basis to those accusations; that there’s no

smoke without fire; that you must admit this queer stuff has gone too far. To

continue in alliance with that rhetoric takes a level of investment in the

nation and the sex-gender system that I think most gay people just don’t have.

At heart, they know who has their back in the fight.

Learning

From the “Bad Gays” of History : A conversation with Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller

about queer crooks, villains, and anti-heros, and what we might learn from the

sinister side of gay politics. By Mad Fox. The Nation, October 26, 2022.

Even

before Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller met, they were on the same page. Both men have

an abiding interest in queer history — Miller as an academic and Lemmey as a

writer of essays and novels. But they found that the kinds of topics they

wanted to talk about, the “beyond 101,” as Miller puts it now, often sounded

intimidating to editors and other gatekeepers.

“We kept being told, ‘There is no audience for this; people aren’t ready,’” Miller explained during a recent Zoom call. So when the pair were introduced by a mutual friend, they decided to go rogue and DIY a podcast called “Bad Gays,” aimed at discussing and dissecting the lives of “evil and complicated queer people in history” as a means of exploring modern queer identity. Neither had any audio experience, but that didn’t matter, they figured. Who was going to be listening, anyway?

As it turned out, many, many people. In late May of this year, the podcast crossed the million-download mark, and Miller and Lemmey published a companion book of the same title. “Bad Gays: A Homosexual History” offers biographical sketches of 14 men, ranging from the Roman emperor Hadrian to J. Edgar Hoover; taken together they explain, as Miller puts it, “how the white gay man happened as an identity figure, and why that was a mistake, and what we should do instead.”

Why did framing the podcast around, as you sometimes say, “queer villains” feel like the right project for you?

Miller: The point of the show is to ask: What do we learn about ourselves by looking at the stories of people we are less comfortable identifying with? It’s not that we’re trying to make a line in the sand between bad gays and not-bad gays. But the more we make ourselves and our listeners uncomfortable, the better the work is.

Lemmey: You immediately start from a position that recognizes complexity. A lot of the people we feature, there’s very few who are out-and-out terrible people. But because we started from this position, we can complicate the stories we want to tell about queerness.

A thing that comes up a lot in both the book and the podcast is that sexuality isn’t an inherent identity category. The concept of homosexuality had to be invented, and it’s a relatively modern invention.

Miller: Both heterosexuality and homosexuality, as we understand them, are this idea that you go out into the world in search of some kind of sexual and/or romantic partner, and that you engage with people in public and private places, and eventually some kind of couple-bond forms. [But] he whole idea of heterosexual dating is invented in the 1920s, when all of a sudden there’s a consumer market for young people. This stuff has a very specific history!

Lemmey: It’s very easy to assume that, after a few generations, they are natural. That’s the main conversation of the book — to look for the historical basis, because within that historical basis there’s a challenge to the idea of these forms being natural. And if they aren’t natural then we can rethink what forms we might want.

So you’re having conversations about people who wouldn’t have identified as gay or lesbian or queer. And we sometimes know something about their sex lives, but we don’t have much evidence. How do you talk around that in a show called “Bad Gays”?

Lemmey: We’re constantly saying: This is our conclusion, but we’re showing our workings; you might come to a different conclusion. There’s the discussion of whether you can label someone who was born before the 1860s as a homosexual in the first place. What does that mean? King James — was he having sex with these men? He was clearly writing in this romantic form about them, but does that mean he was having sex with them? It’s an open discussion we have.

Do you have any favorite stories in the book?

Miller: There’s so much public conversation about the rise of the new right across the West. I think the fact that the person who led that was not only openly gay— Pim Fortuyn in the Netherlands, in 2002 — he was so gay that during the election campaign he gave a TV interview in which he talked about how good [semen] tastes.

I think there is a tendency to equate queerness with radical ideas. But a big theme in the book is looking at how queer people have assimilated themselves into the dominant culture. Why was that important to you?

Miller: Only by understanding how history works do we understand how to work within the world we’ve been given to change the world we’ve been given.

Lemmey: The study of history in this way removes the figure of the queer person as inherently radical, and probably inherently nice, in some way — which is not just ahistorical but an observable falsehood to anyone who hangs out in a gay bar. It can be very helpful in undermining the use of homosexuality as a fig leaf to pinkwash reactionary political projects — and racist and colonialist political projects as well.

It’s Pride Month. What’s your relationship to Pride as a phenomenon, historically and currently?

Lemmey: I love and hate Pride. It can be a really amazing place to discover yourself inside your city. It’s become corporatized and now is a vehicle for some of the most reactionary forces — if you’ve been to Pride in London it’s, like, arms manufacturers and the police — but I think it’s a territory still worth struggling for.

A lot of people say, “Oh, it’s just been turned into a party; it should be a protest.” I think from the earliest days it was both, and one of the things that’s amazing about it is that to party in that way, visibly on the streets, is itself a political action. The personal is political, to coin a phrase.

The book is mostly focused on history, but you do promise to discuss what we should do next. What kinds of queer futures do you imagine?

Miller: We talk about times and places when solidarity has broken out and think about what it would mean to do that in the present. There’s moments like the history of the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union in the Pacific in the 1930s. The union was communist and explicitly anti-racist and explicitly pro-gay; their slogan was, “When they try to get one of us, they get all of us.” They also participated in some enormous general strikes in California in the 1930s that were a really important part of why the New Deal happened: fear of labor action like this one.

Lemmey: One of the things I think the book brings out is that the value of your liberation can go down as well as up, so to speak. The story we have been told of the slow, gradual unfolding of rights in a Western democratic liberal framework is simply false. They can go backwards as quickly as they can go forward, so a politics that demands integration and doesn’t pay attention to those dangers is one that’s potentially lethal to all LGBTQ people, but especially trans people, and that’s what we’re going through in the current moment.

By the same token, in what can seem like a dull, gray, repressive situation — a place like New York in the 1960s, where gay people had been struggling for generations — Stonewall can happen. A revolutionary change can emerge out of the night and sweep things into a new dimension.

‘Bad Gays’ and the two podcasters who love them. By Zan Romanoff. Los Angeles Times, June 6, 2022.

Bad

Gays, a podcast and now a book, argues for a complex and political approach to

queer history; one that stretches beyond examples of past heroism that make us

feel good about ourselves. In place of more straightforwardly inspiring icons

like Alan Turing or Audre Lorde, the Bad Gays project concerns fascists,

tyrants, criminals; the decadent, amoral and problematic. In this sense, it

interrogates both what it means to be gay and what it means to be bad.

Introduced by a mutual friend, hosts and co-authors Ben Miller and Huw Lemmey first

met for a coffee in Barcelona in 2018 – an event that spiralled into a boozy,

nine-hour discussion, during which the idea for the podcast was born.

Since then the podcast has been downloaded nearly a million times and built up a dedicated audience, with the book adaptation published by Verso this month. Beginning with the Roman emperor Hadrian and ending in the early 21st century with far-right Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn, the book offers an expansive view of, in Lemmey’s words, “the creation of homosexuality as something that happened, rather than a natural state of being.” Throughout, Lemmey and Miller take a satisfyingly wide-lens approach, contextualising these personal narratives within changing patterns of politics, monarchism, religion, science, the economy, and imperialism.