In late December 1791, Rose Mainville, a 17-year-old French girl, made a horrifying discovery. She found her name, address and physical description in a pornographic book advertising itself as a detailed guide to the sex workers of Paris. Ashamed, humiliated and terrified at the thought of being confronted by her family, friends and neighbours, she took her own life by drinking a bottle of nitric acid.

Amid the tumult of the early years of the French Revolution, the tragic story of Mainville’s suicide might easily have been forgotten. Instead, it became a cause célèbre, with newspapers across Paris reporting on the story. Mainville was cast as an honest, hard-working street vendor who had been the victim of malicious slander. Two Parisian theatre companies even staged a dramatisation of her story in order to rally public opinion in her defence. Journalists called for the pornographic book to be banned, and for the book’s anonymous author to be punished. In fact, they argued, many other libellous books and pamphlets, offering similarly revealing information, should be forbidden. A private person should not fear exposure in the public sphere.

If Mainville was alive today, we would call her exposure ‘doxxing’: publishing or publicising an individual’s name, address or employment information, often with malicious intent, so that they are ‘unmasked’ or ‘shamed’. It wasn’t illegal for the anonymous author to include her name and address in his pornographic book. Although she was harmed by this identification and exposure, she had no recourse to justice, nor could she demand a retraction. Mainville’s story shows us how difficult it can be for victims to find justice in a society grappling with the balance between free speech and the right to privacy. All societies decide where this balance lies. In Revolutionary Paris, privacy was a privilege that only the elite and powerful could enjoy.

Mainville lived and worked in and around the Palais-Royal, a site renowned for its association with both liberty and licentiousness. Initially built in the 1630s as a palace for Cardinal Richelieu, the Palais-Royal had a succession of royal owners, ultimately ending up in the hands of the Duke of Orléans, a cousin of King Louis XVI. In the 1780s, the duke dramatically expanded the Palais, adding new six-storey apartment buildings with retail space, and enclosing the palace’s extensive gardens on three sides. This commercial venture was a success, and the Palais-Royal regularly attracted huge crowds to its shops, cafés, theatre and public gardens. Crucially, because it was owned by a member of the royal family, the Palais-Royal lay outside the jurisdiction of the Paris police. This meant that it was a safe space for radical or controversial political speech. In fact, in July 1789, the protests that led to the storming of the Bastille had begun in the gardens of the Palais-Royal.

But the Palais harboured other forms of illicit activity: gambling, stock-jobbing, the sale of pornographic materials. It was also a space for sex work. In the arcades and gardens of the Palais, sex workers walked, talked and mingled with wealthy shoppers, middle-class theatre-goers, and street vendors like Rose Mainville.

The pornographic book in which her name appeared – called the Almanach des demoiselles de Paris – purported to be a comprehensive guide to the sex workers who laboured in the gardens and brothels of the Palais-Royal. Such books were not uncommon in the late 18th century. Almanacs, reference books and city directories were a popular genre, and it is perhaps no surprise that some authors saw an opportunity to parody those works and give them a salacious twist. The author of the Almanach claimed to be inspired by Harris’s List of Covent-Garden Ladies, a well-known London directory of sex workers published between 1757 and 1795.

The entries in the Almanach were sexually explicit and full of jokes and innuendo. Whether or not the book actually served as a practical guide, it was definitely used for entertainment, for masturbation as much as assignation. Attempting a pun about ships and sailing, the author sneered that Madame Dugazon was a ‘large & beautiful frigate’ who, when younger, had been ‘an excellent sailboat, but today she is leaking everywhere. – To plug all the holes … 600 livres.’ If a man wanted to have sex with Adeline, rumoured to be the mistress of a priest, he had to pay 500 livres ‘to say a mass at her chapel’. Even the Revolution and its ideals were subject to ridicule in the Almanach. Madame Laurent was ‘very constitutional’ and ‘knows the rights of man by heart’. This woman was, the author laughed, a true citoyenne, for ‘she admits into her central committee two deputies every day’ and would accept only the Revolutionary government’s paper money as payment.

All of this information, the Almanach argued, served the public interest. The author claimed that his book was most useful for foreigners and provincial visitors, but also could be a valuable resource for Parisian men. Drawing upon eroticising and orientalising stereotypes, the book claimed to provide its reader with a ‘portable harem’, transforming him from a ‘simple citizen’ into a ‘real Sultan’. The author of a rival pamphlet, the Tarif des filles du Palais-Royal, described his own work as ‘an act of patriotism’, explaining that its purpose was to provide information about the true cost of sexual services so as to prevent price gouging.

It may seem surprising that these guides, filled with misogynist humour, dirty puns and political satire, were printed at all. The French monarchy did, in fact, impose strict censorship rules on all printed materials. This did not stop libellous, rude or sexually explicit materials from circulating; it just meant that they often had to be printed outside of France, smuggled in, and sold in secret. Before the revolution, it would have been possible to buy a pornographic work like the Almanach, but only by asking a discreet bookseller about materials kept off-book and under the counter.

But at the start of the revolution, the monarchy was forced to abandon its censorship rules. The Revolutionary government, filled with new ideas about free speech, made it possible for any kind of radical work to be published without oversight. Thousands and thousands of books, pamphlets and newspapers were published and read. While the majority of these works were political, the end of censorship also massively increased the availability and visibility of illicit texts of any kind, including pornographic ones like the Almanach. By 1791, these works were being hawked across the city and under the arcades of the Palais-Royal where Mainville worked.

In the wake of Mainville’s suicide, her defenders in the press argued that the Almanach des demoiselles de Paris had broken these Revolutionary libel laws, and they called for the prosecution of its anonymous author. However, critics of the Almanach were not concerned about the privacy of sex workers, because, as one journalist remarked, these women ‘want nothing more than to be known’. Instead, they worried that sexual slander was damaging to family relationships and, by extension, to social hierarchies and the state. Amid bitterly contentious revolutionary politics in the early 1790s, sexual slander was increasingly used as a political weapon against politicians and public officials. This libellous speech not only undermined public trust in government but also threatened to spill over into disputes between private citizens. This appeared to be the case in Mainville’s tragic tale.

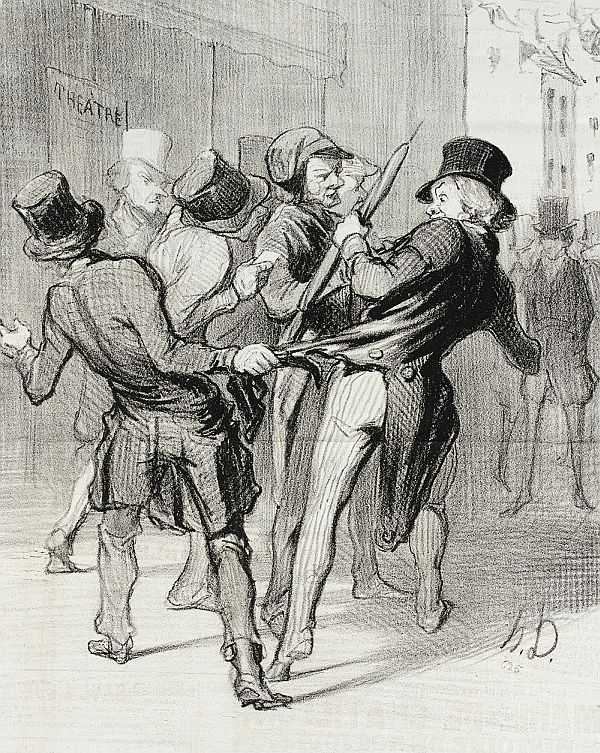

Protests against Mainville’s ‘doxxing’ didn’t appear just in print. Within a month of her death, two theatre companies each brought a different version of her story to the stage. The plays dramatised and no doubt embellished her story, including changing her name to Gertrude. Gertrude, ou le Suicide du 28 Décembre debuted on 25 January 1792 and was performed at least 11 times in the span of two months, while Le Suicide du 28 Décembre 1791, ou les Effets de la calomnie debuted a week later and was performed at least 10 times.

The first to appear, Gertrude, was performed at the Théâtre Montansier, located within the Palais-Royal itself, and was written by a playwright named Joseph Aude who claimed to be personally acquainted with the details of the incident. In Aude’s version of the story, Gertrude Mainville was an honest, hardworking young woman, soon to marry her sweetheart. The play had two villains: Gertrude’s jealous ex-boyfriend, who wrote the Almanach; and Gertrude’s female rival, who sent a copy of the book to Gertrude’s mother so as to intentionally embarrass her in front of her family. Gertrude is driven to despair at the shame and humiliation of these revelations, and is tortured by the anticipated collapse of her engagement. Her head spinning, she swallows a bottle of nitric acid that she had purchased to produce an engraved portrait as a gift for her fiancé. Reviews of the play lauded the performance of the actress playing Gertrude, Anne-Françoise Boutet, known as Mademoiselle Mars. In fact, Mars’s premiere performance was so emotionally wrenching and her physical convulsions on stage so life-like that the audience was reportedly left disturbed and disquieted – so much so that Aude was forced to rewrite the ending of the play to make it more palatable to the public.

Mademoiselle Mars’s riveting yet upsetting portrayal of Gertrude was no doubt inspired by her own experience. Although it was never acknowledged by journalists commenting on the story or reviewing the play, Mademoiselle Mars was herself mentioned very prominently in the Almanach. And Mars was not alone: her two female co-stars in Gertrude at the Théâtre Montansier were also included in the book, as were two actresses at the Théâtre de Molière where Le Suicide du 28 Décembre 1791, ou les Effets de la calomnie was performed. In fact, actresses made up a significant majority of the entries in the Almanach.

The women represented in the Almanach were part of a large and diverse group of people who undertook sex work in Revolutionary Paris. Some women and men did this kind of labour all the time. Others performed occasional or seasonal sex work, soliciting when times were tight or when other jobs failed to come through. Some worked in an organised corps of workers; others worked alone. There were certainly moments of solidarity and mutual aid among sex workers but – just like in any type of employment – there were also rivalries and divisions. Sex workers competed with one another for clients, space and pay.

One particularly unified group of sex workers included women and men who worked in the theatres of Paris. Although not every performer did this kind of labour, it was a truism in the period that many of the people who worked on the stage also acted as companions, lovers or mistresses for the social, political and financial elite. These professionals were well compensated for their time, receiving cash payments, gifts of clothing or jewellery, rent for fashionable lodgings, or even valuable pensions from their patrons. Actresses like Mademoiselle Mars may have exchanged sex for money or gifts, but their relationships were imagined as ‘exclusive’, not in the sense that they were necessarily monogamous, but in that they were private and selective. Theatre professionals managed their sexual relationships carefully, cultivating an aura of erotic singularity, where potential patrons were vetted and assessed before being accepted. This was one reason why inclusion in the Almanach was so damaging. It was not just that elite sex workers did not like to be imagined as people who solicited passers-by in the gardens of the Palais-Royal; it was that they risked losing the air of fashionable rarity that might promise a more secure and lasting livelihood. They definitely did not want men showing up at their homes uninvited, clutching a copy of the Almanach and its advertised sum.

Mainville was not an actress – her name does not appear in any of the period’s theatre guides – but it is more difficult to know how she made her living or why she was listed in the Almanach. Although the two theatrical performances and the newspaper articles about her death consistently portrayed her as a street vendor, other evidence is less conclusive. Some elements of her story suspiciously resemble well-worn narrative tropes of the late 18th century. At least one journalist, even as he protested her innocence, described Mainville as ‘a sausage seller’ at the Palais-Royal, perhaps a not-so-subtle wink at male readers keenly aware of the location’s reputation as a centre of sex work in Paris. It is also important to note that another guide to sex work at the Palais-Royal, the Tarif des filles du Palais-Royal, most likely published in 1790, listed a woman named ‘Mainville’ at an address similar to the one in the Almanach. Perhaps Rose Mainville was a sex-worker at the Palais. Perhaps she was only a street vendor there. But this ambiguity is not surprising, especially given the diversity of sex workers in Paris.

No matter how she supported herself, Mainville certainly had something in common with Mademoiselle Mars and the other actresses listed in the Almanach: her reputation, her livelihood and her connections with family and friends may have been threatened when she was revealed as a ‘prostitute’ in print, but the legal system afforded little recourse. Absent prepublication censorship, anyone could publish anything, whether it was a controversial political opinion or a sexual slander. New Revolutionary free speech laws did allow for civil and criminal prosecution of authors who wrote slanderous works, but only after they appeared in print – in other words, after the damage had already been done. And even these legal remedies were of limited use. Prosecution was difficult in cases where books or pamphlets did not reveal their authors or publishers.

In the case of the Almanach, Aude, the playwright of Gertrude, claimed to know the true identity of the author, but there is no evidence that this person ever faced charges. Criminal or civil lawsuits would have been expensive and would have invited additional unwelcome public scrutiny of women who had already suffered damaging exposure. In its practical application, the law permitted the author of the Almanach to protect their anonymity even as victims lost their own, their private lives and livelihoods exposed to a voyeuristic and potentially dangerous public.

Technically in possession of legal rights but deprived of any realistic ability to exercise them, many women who appeared in the infamous pages of the Almanach would have felt as powerless as Mainville. But Mademoiselle Mars and the other actresses did have one very potent weapon at their disposal: the stage. By taking up Mainville’s cause and reimagining her story in front of their audiences, they crafted a compelling and sympathetic narrative designed to undermine and publicly shame the author of the Almanach. This approach, too, had limitations. Given the public’s hostility towards sex work, Mars and her fellow actors had to cast Mainville as an ‘honest’ and ‘innocent’ young woman unfairly slandered in print. To describe her as a sex worker, even on the stage, would have invited criticism of her story.

This story suggests some valuable lessons that might inform how we think about more recent cases of doxxing of sex workers, who have been targeted because their labour supposedly blurs the line between public and private, what is shared and what is kept separate, what is allowable as a freedom of the press and what constitutes a gross invasion of privacy. Doxxing is unethical as well as, in some cases, illegal, but its victims have found that they cannot rely on the law to protect them. Neither the government nor social media companies take the problem seriously enough and, as in the case of the Almanach, by the time private information is removed from public view, significant damage has already been done.

In November 18, 1850, a Monsieur Langangne decided he had had enough and took up his pen to write a letter to the police. Having the habit of taking an evening walk “en flâneur” from the Madeleine to the Faubourg Montmartre in what was then the first arrondissement (now the eighth), Langangne wrote that he had begun to notice “spectacles of shameful immorality that have painfully afflicted my sight and my spirit.” These spectacles, he specified, were none other than “those offered by those beings without name, those hideous hermaphrodites!” He explained that so long as their behavior remained within “certain limits, he kept quiet, but that is impossible now that the activities of these unfortunates (who no doubt also portray themselves as advocates of the right to work, since bad examples are contagious) reach the alarming heights of organized blackmail.” Indeed, Langangne proceeded to describe how, the previous day, he was “accosted” by two young men with “cheeks painted with makeup,” who claimed to know him and who asked him to buy them some drinks. Surmising that the reason they approached him was that “he may have something in common with one of their brothers or friends,” Langangne refused, which led the two men to launch a series of insults at him. This unpleasant encounter convinced this particular Parisian that “the boulevards are currently a veritable court of miracles planted in the middle of Sodom and Gomorrah, and soon all promenades on them will be forbidden not only to honest women who have not been able to show themselves for a long time, but also for men who should not have to be at odds with rascals.”

As an employee within the Ministry of Finance, Langangne seemed to expect that the streets were in some ways “his.” His right to them certainly outweighed that of those “hermaphrodites,” a faith indicated by his self-identification as a “flâneur.” The idea of the “flâneur” encapsulates a form of urban wandering predicated on class and gender privilege that permitted movement and observation of the attractions of modern city life. The act of flânerie depended on the management and maintenance of perception, the clear control over what one saw and heard, as well as one’s response. More broadly, as scholar Vanessa Schwartz has described it, the flâneur represents “a positionality of power—one through which the spectator assumes the position of being able to be part of the spectacle and yet command it at the same time.”

By asserting himself as a “flâneur,” then, Langangne referenced a whole host of assumptions about his place within the urban environment, all of which revolved around his ability to move about, look on, and assert himself within urban space as he wished.

Langangne was not entirely successful at asserting his own respectability against the disrepute of the men he encountered. The letter notes, after all, that he was only writing because the hermaphrodites’ behavior had exceeded “certain limits.” Presumably, in other words, they had been present before this moment, fixtures of a broader neighborhood culture that became an annoyance once they specifically targeted him. In addition, his admission that the “hermaphrodites” may have addressed him because “he may have something in common with” them highlights his difficulty in distinguishing his own identity from those who accosted him.

Although the letter may have tried to construct the writer’s knowledge against the supposed ignorance of its objects, that knowledge was, in fact, premised on Langangne’s own familiarity with his targets: he knew how to recognize them through their behavior and dress. That he may have “resembled” them reinforces the difficulty he faced in separating himself. He could know who they were only if he was in some sense already one of them. The “straight” flâneur thus becomes decidedly queer, because we can ultimately never know who he was: a victim or a participant in a culture of public sex.

The use of public space for sex should not be seen only in terms of anxiety by regulators and Parisians, but also as a practice that actively shaped the ways people encountered urban space.

During this period, expert commentators, the police, and lay Parisians believed that sex was increasingly available and unavoidable on the streets of Paris. At the same time, the redevelopment of the city oriented it even more toward its image as a site of commercial “pleasure.” This combination—an emphasis on the dangers of public sex and a social world that revolved around seeking out public pleasure—made sexual knowledge more essential to experiencing the city at the very time when it seemed that sex was escaping its boundaries. As the brothels failed and men who sought sex with other men were more apparent, the need to recognize the possibility of a sexual encounter, whether in order to pursue or avoid one, became more important. Public sex, therefore, should not be seen as an “other” practice against which “dominant” “norms” were defined, but rather as one way the city emerged in the first place. The need to know how to understand the possibility of encountering public sex disrupts any easy division between supposedly “illicit” forms of public sexuality and “licit” forms of social practice. Such a distinction, rarely named but often implied, never actually cohered.

As Haussmannization oriented the city around the flow of capital, commerce, and the middle classes, the congruence between sex and commercial pleasure became increasingly problematic as the police and expert commentators considered the regulation of urban space. It was one thing to accept the presence of venal and immoral sex in areas of the city already associated with working-class debauchery as a necessary safety valve. It was another when such practices took center stage in spaces devoted to middle-class and elite Parisian consumption.

And while it is difficult to precisely map the areas of the city where such encounters occurred, both the police and many Parisians began to see sex everywhere they looked. Encounters premised on these forms of sexual knowledge created a new sexual public.

Sexual solicitation had wider ramifications for how users of public space understood their own role. For instance, an 1872 letter complained that “an honest man can no longer walk peacefully on the cours la Reine [near the Champs-Élysées] between 9 and 11 at night without being accosted by women who engage in revolting touches and direct the following verbatim proposition (Do you want me to jack you off?).” The writer apologized for using such explicit language, “but it has been used by many of the ignoble creatures.” That these encounters bothered him enough to write, that they stayed with him after he moved on, highlights the ways sexual solicitation created new feelings and emotions that were anything but momentary.

The letter stands as evidence of the creation of a broader sexual public (who else heard these words?) even as it highlights how the individual writer’s sense of self changed in some undefinable way in response to the encounter. In another instance, a man named G. Feuille wrote to the police in 1880 to complain: “It is scandalous…to see oneself attacked (assaili) and almost violated (violenté) by several prostitutes, who direct at you the most filthy remarks.” The violation implied here may not have actually been sexual assault as the French word violenté may imply, but the connotation remains significant. That this man felt sexually assaulted by women who put themselves at the service of male clients highlights the inversion at play as men were forced to reckon with their own sexual response. In both cases, the unwilling participation in a public sexual culture threatened the urban experience as imagined by privileged male pedestrians.

The “violation” felt by these two men at the attention of female prostitutes disrupted their ability to move about the city as they so chose, but it did not necessarily put into question their status as potential clients. Insofar as these “assaults” may have elicited a sexual response, they may have heightened their awareness of their status as sexual beings even as it challenged their gender privilege.

These possibilities often proved problematic for women who wished to also enjoy public space. An 1872 letter signed by multiple residents of the boulevard de la Villette, for instance, claimed that the street was so encumbered that a wife and child could not exit their house without being taken as prostitutes by men who were constantly on the lookout. The expectation that sex was available thus shaped how these residents were understood by those who saw them. As others have argued, the common assumption that a woman in public was a public woman placed all women, but especially working-class women, in a vulnerable position. The emphasis on the threat of the prostitute by the police and Paris residents tended to increase the association of public space with the possibility of venal sex, which, in turn, shaped how women encountered the life of the city. This is not to say that all women who appeared in public were assumed to be sexually available, nor that middle-class women were forbidden from the streets. The streets enabled a wide variety of encounters, dependent on the particular circumstances in which they occurred.

In fact, rather than two possible categories—honest and dishonest—into which an unsuspecting woman could fall, movement about the city made such categorizations highly contingent. For example, on the evening of January 19, 1874, two police inspectors arrested a woman named Valerie Durand, a thirty-three-year-old piano teacher. According to the police, the officers were taking a prostitute to the station when they came across “a woman, alone, standing in the middle of the boulevard, next to a garden where they claimed to have seen her address several individuals.” One of the officers then turned to his partner, “saying to him, ‘Look over there, since you know the women of this neighborhood better than me, if that’s an unregistered prostitute.’ ” The partner, so the police claimed, decided to approach the woman only after “recognizing that she was looking at men in a provocative manner.” Asked what she was doing there, she responded by saying she was waiting for her husband and refused to give her name. She was then arrested and taken to the station, where she admitted to having lied about being married and “that in reality, she was waiting for a man who was employed in a factory, and, finally, that she was perfectly free to wait for whomever on the boulevard.” She claimed that she was on her way home when she was arrested after stopping to button herself up. During the course of her arrest, the officers refused to check her story at her home, or even by asking an acquaintance living in the same building as the commissariat of police, before sending her off to the depot. Police confidence in their ability to tell who was and who was not actually a prostitute, reliant on such vague attributes as a provocative glance, thus determined their will to act.

Durand’s situation on the one hand highlights women’s vulnerability. But on the other hand it illustrates the ways that the assumption of prostitution was never so stable as to totally delimit someone’s ability to act. For Durand’s actual identity was never fully determined in the police documents. Was she innocently returning home, as she claimed? Or was she waiting for a “male friend,” as she also claimed? Perhaps the police were right and she was actually looking for a sexual client. The police eventually let her go, but despite having received “the most favorable information on her family,” they still argued in favor of the “facts certified by the police agents.” Indeed, the police superintendent took the opportunity to assure his superiors that he would “be even more circumspect regarding unregistered prostitutes who are vouched for by honorable persons.” This indeterminacy enabled Durand to be released to her family not only without being condemned as a registered prostitute but also without admitting to being totally honest. Perhaps Durand was an innocent working woman out for a date who got caught up in an awful situation. But perhaps she was actually a prostitute able to use the thin line between her own profession and that of other (honorable) women to her advantage to get off the hook.

Although far from typical, this case of apparently false arrest demonstrates two essential aspects of the public sexual culture. On the one hand, the moral discourse of prostitution did leave women vulnerable. The public sexual culture remained hierarchical, predicated on gendered and classed relationships. But it also provided, on the other hand, if not evidence of the opportunity for resistance, then at least the possibility of a different understanding of sex in the modern city outside the binaries of honest and dishonest, registered and unregistered. The administrative category of the prostitute struggled to remain solid in the face of the uses of the street. Valerie Durand’s success at evading registration without falling into the category of the honest is but one example of the ways that late nineteenth-century sexual culture could not be slotted into a discrete set of categories.

Between the Streets. By Andrew Israel Ross. Lapham’s Quarterly, September 26, 2019.

C’est peut-être un goût pervers, mais j’aime la prostitution et pour elle-même, indépendamment de ce qu’il y a en dessous. — Flaubert

Some years

ago I acquired a small, modest-looking French book published in 1826 that would

become the source of my interest in women and prostitution in Paris, especially

after the French Revolution. It was a 32mo bound in plain crimson boards, small

enough to fit in one’s hand or pocket and titled Dictionnaire Anecdotique des

Nymphes du Palais-Royal et autres Quartiers de Paris par un homme de bien. In

124 pages, the anonymous author lists scores of Parisian prostitutes

alphabetically by their first names, from Adelaide to Zoe, and gives the

streets where they could be found along with descriptions of their physical

appearance and personalities, including:

Olympe, rue

du Richelieu, who is beautiful, tall like a man, and is said to flirt with the

lovers of her friends — and that her desires are not always satisfied by just

one.

Véronique

(La Blonde), rue Traversière, is far from pretty, but her blond hair, falling

with grace over her beautiful pale skin, sets her apart.

How, I

wondered, did a society perfect prostitution to such a degree that a dictionary

of hookers could be published as easily as a glossary of words, a bibliography

of books or a tourist’s vade mecum? With this little guidebook in hand, a man

in the 1820s could save the wear-and-tear of prowling the streets in order to

find an appealing nymphe to suit his erotic tastes — it was almost like

choosing a chocolate from a box of assorted flavors, or even a breeding

stallion from a stud book. And who was the gentleman, the homme de bien, who

wrote it? In a short preface, hoping to avoid complications lest he be

discovered and considered a pimp, he disavows knowing any of the women

described, claiming that he merely received the information from others.

Somewhat unexpectedly, he then rails against a society that preaches morals but

permits vice, and urges fathers to protect their children against prostitution.

How? By reading his book. The list of nymphs begins immediately after this

peculiar suggestion.

Intrigued,

I began to piece together what I knew about post-Revolutionary France with the

mystery of my little dictionary. It took me thirty years to solve the riddle of

the nymphs, which I will get to shortly. But before I was able to zero in on

that, I began to look for clues in other books, and started to assemble a

collection of material on Parisian prostitution — from the fall of the Bastille

to the rise of the Eiffel Tower — and discovered an entire genre of books and

prints devoted to it. In fact, I began to realize that prostitution was at the

epicenter of the era. A frequent visitor to Paris, I was aware that the capital

was (and still is) fueled by large quantities of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol

and sugar, but I was unaware, until I began my quest, that prostitution had

formerly been as fundamental to Parisians as those other stimulating staples.

My next

discovery, a major one, proved pivotal: Alexandre Parent-Duchâtelet’s De La

Prostitution dans La Ville de Paris, 1836. Issued in two thick 8vo volumes a decade after

my petite Dictionnaire, it is not a guide to pleasure but rather, an extensive

textbook, the first attempt to investigate and analyze prostitution

scientifically in order to create effective solutions to the problems it was

creating. The alluring sirens described in my dictionary, the nymphs who had

been sought by flâneurs, philanderers and married men, had become, within ten

years, clinical objects of scientific inquiry. Studied as exotic specimens from

the animal kingdom, they were probed, questioned and examined by doctors and

experts in the newly emerging fields of hygiene, statistics, and sociology. In

ten years, a portable, somewhat prurient

“gentleman’s guide” had been displaced by a substantial, authoritative,

government-sponsored work on prostitutes’ sexual habits, health, and attitudes,

one filled with analytic texts and tables based on facts; it became a

shape-shifter.

[Anonymous

artist]. Allons, voyons, voulez-vous monter? (Come on, look, do you want to go upstairs?) Handcolored etching, 1815. Frontispiece to

Déterville, Le Palais-Royal ou Les Filles en Bonne Fortune, 1815. Nymphs at the Palais Royal invite

soldiers and other men up to their rooms. This little book was intended as a

guide to initiate young men into the world of sex and prostitution.

Parent-Duchâtelet

(1790-1836), its author, was a medical doctor who had worked for France’s

nascent public health services in the 1820s and had been successful in

organizing the first campaign to clean and sanitize the sewers and cesspits of

Paris, which were beginning to be recognized as sources of infectious diseases.

His unstinting investigations (he regularly descended in the city’s foul lower

depths) led to a major report advising on how best to unclog, clean and

disinfect the sewers of Paris in 1824.

Parent next

turned his clinical, pragmatic mind to the public health problem posed by

prostitution after being contacted by an unidentified colleague who wanted to

research and publish a study of prostitutes in order to rehabilitate them but

who could not afford to do so. When this gentleman unexpectedly died, Parent

sensed an opportunity, and recognizing the importance of prostitution as a

medical issue rather than a moral one, and with the resources of the state

behind him, took on his colleague’s project, stating: “I have found in most

minds a particular disdain attached to the functions of all who, in one way or

another, deal with prostitutes… I could not understand this excess of delicacy…

If I have been able, without scandalizing anyone, to descend into the

cesspools, to touch putrid matter, to spend part of my time in the refuse pits

and to live, so to speak, in the midst of all the most abject and disgusting

products of human congregations, why should I blush to tackle a sewer of

another kind [i.e.,prostitution], a sewer more filthy, I confess, than all the

others, but the study of which offers me the hope of effecting some good?”

It was only

logical. Sewers and prostitutes, each receptacles of human bodily excreta,

could be cleaned and regulated scientifically, and because prostitution was

legal in France, the task could be undertaken in an orderly fashion. This

seemingly liberal approach to prostitution was a result of Enlightenment

thinking that recognized the futility of suppressing male sexual desire while

attempting to keep men disease-free through the medical regulation of

prostitutes — it was they, and not their clients, who were required to undergo

physical exams. What could be more reasonable? The new law codes of the

Revolution that replaced those of the Ancien Régime made no mention of

prostitution, and as it began to proliferate in the 1790s, the usual problems

arose, from serious crimes to public disorder and disease — but it was not

outlawed. Regulation, not eradication, became the goal, and brothels soon came

under the supervision of the police. By 1823, all brothels were licensed and

regulated, but a new problem arose: although registration was mandatory, many

women worked illegally, that is, without a permit.

The

problems posed by prostitution, along with general health issues, continued to

grow. In 1832 a cholera outbreak killed 20,000 Parisians while the number of

prostitutes in the city reached an all-time high of 43,000 (out of a population

of about 750,000). The health risks to both men and women from venereal and

other diseases were becoming severe, the issue of public health as a responsibility

of the state was emerging and the police were having trouble keeping up with

the supervision of both legal and illegal prostitutes. Something had to be done

to halt this threat to social stability, and Parent was the man to do it. The

results of his work were published after he had spent a decade investigating

the “sewer of another kind.”

In

twenty-five chapters, Parent, who died of exhaustion the year his work

appeared, discussed every aspect of Parisian prostitution by categorizing the

prostitutes physically, geographically, medically and economically; he

suggested methods of police and medical controls (he was an advocate of

regulated brothels), and even proposed a way for prostitutes to pay taxes. He

also supported the formation of institutions where women who had renounced

prostitution could go to reconstruct their lives, taking a cue from his

anonymous colleague. Throughout the entire work, and all subsequent works to

follow on the subject, prostitution was seen as an exclusively female problem —

not once is male sexuality called into question for requiring it.

Parent

created lists and tables showing the distribution of Parisian prostitutes by

quartier, surveying areas throughout the city including the Île St. Louis,

where, alone among neighborhoods, there were none; the Place Vendôme, where he

found thirty-nine; and the Palais Royal, center of all things illicit, where he

counted 346 prostitutes. They were also grouped by street, by suburb, and by

which département in France they had come from, even by which floor of a

building they most frequently occupied. (It was the French first floor, the

floor above street level.) Parent took advantage of the information supplied to

him by the police, who, in 1816, had begun to keep more accurate data on the

prostitutes they arrested than they had previously. By 1832, he had access to

just over 5,000 records which included information on each woman’s place of

birth, the occupation of her father, the determining causes of her becoming a

prostitute, her education level, the number of children she had, as well as the

age at which she registered as a prostitute. (The ages ranged from ten to

sixty-five.)

Pierre-Numa

Bassaget, called Numa (1802-1872) [attrib]. Boulevard St. Denis.

Chromolithograph, c. 1855. A prostitute from the Boulevard St. Denis fondles

her jewelry while exposing some flesh. Such images provided source material for

later artists, including Manet; the link is especially evident in his Olympia

(1863).

Yet within

this methodical work, I found one bit of whimsy, certainly unintended, that

called to mind my Dictionnaire: in a chapter on the pseudonyms prostitutes gave

themselves, Parent included a double-columned table of these assumed names,

arranged by social class. The first column contains the Classe Inférieure,

including such ribald, lewd, and comical nicknames as Rousselette (Little Red

Pear), Poil-Long (Long Hair), Belle-Cuisse (Nice Thighs), Faux-Cul (Fake-Ass),

and Raton (Little Rat). In the second column, the Classe Elevée, are such names

as Amanda, Calliope, Delphine, Paméla, Olympe, and Flore, names associated with

Greek mythology, literature or the upper class. This classification by descriptive

name was maintained throughout the century, helping men choose women based not

only on her physical attributes, but also on what class she was likely to be

from as revealed in her nickname. Later, the astute and often pontifical

observer of women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Octave Uzanne,

used the exact same method to describe Parisian prostitutes in 1910:

“At the

very bottom of the ladder is the woman who haunts the fortifications… The

soldiers do not even know her name; they call her la paillasse… A much more

formidable species of prostitute is the gigolette [who] is almost always young,

and often pretty… There are grades and degrees in all this peripatetic

prostitution… In Paris, there are about 60,000 filles insoumises. They constitute

the main part of what [is] called middle-class prostitution.”

As for

upper-class prostitution, Uzanne refers to it as “clandestine prostitution” and

the women who represent it are known as belles petites, tendresses,

agenouillées, horizontales, and dégrafées. He also refers to Parent,

complaining that of all the writers on prostitution who came after him “not one

has sounded its deepest depths or probed its darkest mysteries.”

Many tried.

Parent’s formidable work became the cornerstone of a staggering amount of art

and literature — he has been called “a veritable Linnaeus of prostitution.” Balzac,

Flaubert, the Goncourts, Hugo, Huysmans, Sue, and Zola were all familiar with

Parent and each created novels based on the lives of prostitutes that were

based, in part, on data gathered by him. In art, the prostitute became a

frequent figure in the caricatures and chromolithographs of the 1840s-1860s, as

she did in the subsequent works of Manet, Degas, Lautrec, and Picasso, whose

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) refers not only to the name of a Barcelona

brothel, but also — and originally — to one of the old slang words for

prostitute, Pont-d’Avignon, so-called for

the bridge under which many prostitutes met their customers during the

Avignon Papacy in the 14th century. Sur le pont d’Avignon on y danse, on y danse.

But perhaps

Parent’s most devoted acolyte was Alexandre Dumas (père), who acknowledged him

not only on the first page, but throughout Filles, lorettes et courtisanes

(1843), his analysis and description of the Byzantine typology used to describe

each of the three levels of Parisian prostitution, elaborating on Parent’s

original list. From the lowest working-class filles de la Cité (known as

numéros, chouettes, calorgnes and trimardes), to the middle-class filles du

boulevard (grisettes, lorettes, ratons, louchons), and up to the highest level

of filles en maison (courtisanes, femmes du monde), Dumas inventoried them all.

Although such terms were included in other works, notably those on slang, no

other book had been devoted exclusively to the subject, and in such a literary

way. As Dumas observes in his introduction: “Here is a corner of the grand

Parisian panorama which no one has dared to sketch, a page in the book of

modern civilization whose base is a word no one has dared utter.” Dumas had the

audacity and honesty to assert that prostitution was at the base of Parisian

society. He wasn’t wrong.

Alphonse Liébert

(1827-1914). Adah Isaacs Menken and Alexandre Dumas. Carte de visite

photograph, 1867. This

photograph was taken on March 28, 1867.

Yet Dumas,

who understood so much about prostitution’s place in 19th century Paris, made

no mention of the sexism that accompanied and regulated it — even though it was

he who coined the phrase Cherchez la femme, inferring that a woman was usually

the cause of most problems. Others, steeped in misogyny, did not hesitate to

express their sexist views, although not as metaphorically as Dumas. Noted

historian and sociologist Jules Michelet held that the social order was in

grave danger due to women’s “weak, atavistic and deranged sexuality” as

evidenced by prostitution. Writing about women’s “natural inferiority,” he

asserted that women were only fit to be wives and mothers. A more brutal

attitude suited Pierre Joseph Proudhon, the influential philosopher known for

his socialist-libertarian politics and for being the “father of anarchism.” He

was also an extreme misogynist whose views, although widely shared, were rarely

put into print with such viciousness. He did not think twice in declaring in

his most shocking work, La Pornocratie (1875), that a woman was capable of

being only “a harlot or a housewife” and that “a woman does not at all hate

being treated with violence, indeed even being violated.” (Little wonder that

so many women, thwarted and abused mentally, emotionally and physically, were

diagnosed with “hysteria.”) Many of these presumptuous attitudes about women

may be traced back to Parent, whose classification and regulation of

prostitutes heralded the 19th century’s determination to proscribe women’s

opportunities, education, and sexuality. Yet Proudhon’s words seem more

monstrous than most, and I wondered how deeply his views were embedded in

French culture. With Dumas as a guide, I began to compile my own list of French

synonyms for prostitute, reasoning that such words would reveal a great deal

about how the French regarded women and sex. I didn’t realize just how long the

list would become — it now has 400 entries. I discovered that the majority of

the words were fanciful, imaginative, allusory or metaphorical; many were

facetious and derogatory; and some were outright expressions of disgust, à la

Proudhon, including salope, latrine, and cul crotté (filthy woman, latrine, and

shit ass.) The crudest words were, like anarchism’s father, in the minority,

but they do exist.

Having

collected so many words, I decided that a good place to study their evolution

would be at the beginning, in the first French dictionary, Jean Nicot’s Thrésor

de la langue françoyse, tant ancienne que moderne (1606), in which Nicot

includes courtisane, cantonnière, fille de joye [sic], paillard, chienne, and

putain. From this base, the vocabulary would multiply over the centuries, but

Nicot’s six words would remain stalwarts, persisting along with the

classification of prostitutes based on the rank of their clients. The

courtisane would remain at the top — the lover of aristocrats and the rich —

while the clients of the filles de joie and paillards were from lower ranks,

but whatever their station, men had no trouble finding women to hire for sex:

prostitution is as much a part of Parisian history as Notre Dame, and as

important — the city, its streets and its prostitutes have had a long-term

relationship. As my little dictionary indicated, women and streets were

intimately linked: the pavement nymphs and roadside flowers — the fleurs du

macadam — were categorized by the street names or area where they worked, and

had been for centuries.

A study of

some of Paris’ old street names reveals the longevity of the link. The tiny rue

du Pélican might strike one as merely fanciful since pelicans don’t roost in

Paris, but the name derives not from sea birds but from its bawdy 14th-century

name: the rue Poil au Con (Puss Hair Street), so-named for the many prostitutes

who worked there; with a nod to propriety, the street later assumed its less

vulgar homophone. Similarly, the medieval rue Pute-y-Muce (Hidden Whore Street)

would later become the rue du Petit Musc (Little Musk Street).

The lure of

the streets was so potent that each image in Les Lionnes de Paris, a set of

chromolithographs depicting individual prostitutes published circa 1855, shows

each one identified only by the dress and décor of the street or neighborhood

where she could be found: each title is the name of a street. The cocotte from the

Boulevard St. Denis (currently and historically known for prostitution)

reclines seductively on her lush bed, her left breast exposed as she fondles a

gold necklace — prostitutes were typically portrayed as rapacious deceivers. As

the Goncourts declared, “Women only consider their sex as a livelihood!… their

sex is a career.”

Philippe Jacques

Linder (1835-1914) [attrib]. L’Anglais à Paris. (An Englishman in Paris.) Color lithograph, c.

1867. An Englishman eyes a young woman while holding his map of Paris, an

allusion to a “streetwalker.” The artist cleverly mocks the man by placing the

figure of a punchinello behind him.

Other such series enjoyed great popularity in the mid-19th century, and these popular prints often became source material for later artists. Manet, whose modern, penetrating eye never failed to see things as they were, did not hesitate to choose his subjects from everyday life, including prostitutes; he must certainly have seen the chromolithographs of the 1850s before creating his notorious Olympiain 1863. Its scandalous subject matter — a confident courtesan wearing only a neck ribbon, earrings, a gold bracelet, some dainty slippers and a flower in her hair — echoes the chromolithographs from the 1850s, but instead of calling his subject by a street name, Manet chose “Olympia,” a name associated with prostitutes, and one that was in Parent’s original list.

Having

learned so much about Parent and his influence, I was still in the dark about

the anonymous author of my dictionary, the anonymous homme de bien, until a

short while ago. Thanks to persistence, luck and the Internet, which did not

exist when I acquired the book, I identified him, and the circumstances

surrounding the dictionary’s publication — and destruction. I had already been

able to find the book listed by title in several bibliographies of French

books, and that the Bibliothèque Nationale apparently had the only

institutional copy extant, leading me to believe that the book was very rare,

and to assume that the edition size had been small. But why would someone go to

the trouble of compiling such a dictionary and print very few copies

considering that the demand for such a book would have been enormous. Information

on edition sizes prior to the late 19th century is difficult to find, and

especially so for such an obscure book as the Dictionnaire — or so I thought.

From time

to time, I would check the Internet to see if any new information had surfaced,

and during a recent search, I found it cited in two obscure reference books

that I did not know and had never seen before: Fernand Drujon’s Catalogue des

ouvrages écrits et dessins de toute nature poursuivis, supprimés ou condamnés

(1879) and Antoine Laporte’s Bibliographie contemporaine: Historie litteraire

du dix-neuvième siècle (1887). Each citation had more information than was included

in the standard bibliographies, which repetitively included only the title,

publisher and date. In these newly discovered reference works, I at last found

the author’s name: Charles Lepage. After a bit more searching, I learned that

he was a poet, singer, writer, journalist and inventor who was born in 1803 and

died in 1868, making the dictionary a work of his youth. What astonished me was

the short note in both entries indicating that the dictionary had been

destroyed by the authorities with the consent of the author as per a court

judgement of December 15th, 1826, making the book “very rare if not very

interesting” according to Laporte. This was shocking news in itself, but Drujon

included one small parenthetical word, Moniteur. Armed with this lead, I

discovered that he was citing Le Moniteur Universel, a long-running daily

Parisian newspaper. Now all I had to do was find the actual article. Thanks to

the Bibliothèque Nationale’s online services, I did.

In a

triumph of French bibliophily, every issue from 1790 to 1901 is available

online, and knowing that the article must have appeared on December 15 or soon

thereafter, I read through those of December 15th and 16th with no luck, but

found it in the December 17th issue under the headline The case of the

Dictionnaire anecdotique des Nymphes du Palais-Royal was settled yesterday. I

had tracked it down! This is the sort of discovery that makes a biblio-sleuth

ecstatic, and I was. The article reported that the case against the author had

been settled; that Lepage still had 600 to 700 copies of the little book; that

the court had found the book to be shameful but not illegal; and that the

author had agreed to destroy his remaining copies. This led me to believe that

the original edition size had been perhaps 750 or 1000 copies, and that after

the destruction of Lepage’s remaining copies, only a handful had survived,

including mine.

I soon

discovered more about the book’s legal history, finding the transcript of the

trial online in an issue of the Gazette des Tribunaux, December 9, 1826. Lepage

was not the only defendant. The printer, publisher and three booksellers also

had to face the tribunal for “facilitating vice” by circulating the addresses

of prostitutes and for violating several statutes of an 1819 censorship

law.

The lawyers

for the accused presented their case in a very clever, droll and literary way

by first asking the court how it could prosecute those involved in a book on

prostitutes when prostitution itself was legal. As one said: “I blush to say

it, but prostitution is in the public domain.” They went on to describe Lepage

as a young man, just out of college, whose innocence was equal to the indecency

of his “heroines” and that the book was a reflection of nothing more than

Lepage’s naïveté. The lawyers suggested that instead of sentencing the author

to prison, the court should require him to read his dictionary for eight hours

a day, which, they assured the court, would be punishment enough. They

concluded by reminding the court that the dictionary was nothing more than a

pale imitation of an actual visit to the Palais Royal (the center of Parisian

prostitution), which could be truly upsetting. They conclude by quoting

Horace’s Ode IV, To Sestius, a paean to pleasure. With their adroit arguments,

they won the case. Lepage destroyed the remaining books, and the Dictionnaire

was duly placed on the Vatican’s list of prohibited books. Later, it was cited

in several bibliographies and generally forgotten.

But I still

had a further question: Why was this book singled out for prosecution? There

had been a flurry of dictionaries of prostitutes in the 1790s, when flaunting

decadence and vice became de rigeur during the Revolution and when the

unprecedented porno-libertine works of the Marquis de Sade were published;

other such books were published well into the early 19th century. Yet this

little dictionary, a pale descendant of its predecessors, was scandalous enough

to initiate a criminal prosecution. I surmise that in the 1820s the book evoked

the licentious and radical early-1790s, the memories of which would have been

especially disturbing to the conservative Bourbon king Charles X and his prime

minister, Joseph de Villèle, an ultra-royalist known for imposing strict

anti-press and anti-sacrilege laws.

On December

29, 1826, just days after Lepage was acquitted, Pierre-Denis Peyronnet, the

Minister of Justice, proposed a new law that imposed harsh new sanctions and

penalties on the press; he called it “the law of justice and love.” It was

anything but that, and upon hearing of its severity, one legislative deputy

left the chamber shouting: “You might as well propose a law for the suppression

of printing in France, for the benefit of Belgium.” The reaction to the

proposed law was swift and powerful, from members of the Academy to the public

at large — the majority of the country was horrified and protested. The bill

was withdrawn in April, but it and other manifestations of repression resulted

in a bill of impeachment for Villèle, who was removed from office in 1828,

presaging the July Revolution of 1830 in which Charles X was forced to

abdicate. Perhaps the little dictionary was the last straw for the

ultra-conservative government, or perhaps it was a coincidence, but the desire

to impose heavy restrictions on the press followed the Dictionnaire’s court

case.

Lepage,

undeterred and perhaps inspired by the government’s failure to pass the

repressive law, wrote (with his friend and frequent collaborator Emile

Debraux), two satiric works in 1827 on his former tormentors. The first,

Villèle aux Enfers, was a satiric verse on the punctilious prime minister. The

second work, Peyronnet devant Dieu, satirized the authoritarian justice

minister.

Lepage went

on to a successful career as a singer and writer of popular songs. An ardent

voice for the people, anti-royalist, and member of the emerging bohemian class,

he sang his way to fame in the goguettes of Paris, the many small,

working-class bars/cafés devoted to communal singing, drinking and socializing

where goguettiers often sang about love and women, including prostitutes, with

lyrics using some of the other names for nymphes, as in “Le Boudoir,” a popular

19th-century ditty:

Voyez-vous,

lion, rat, grisette,

Encombrer le

sacré parvis;

Par

Notre-Dame-de-Lorette

A l’enfer

criminels ravis?

Aux frais

minois qu’on y contemple,

Aux parfums

sentant leur terroir,

On se dit :

quel est donc ce temple ?

Est-ce une

église, est-ce un boudoir?

[Can’t

you see, lion rat, grisette,

That by

cluttering up the sacred space

Around

Notre-Dame-de-Lorette

You’ve

thrilled the criminals in hell?

To the

fresh little faces one sees there

To the

perfumes redolent of a bazaar

One

asks, what then is this temple?

Is it a

church, or is it a boudoir?]

Church or

boudoir? Sacred or profane? Virtue or vice? Lepage’s Dictionnaire, a vestige of

the libertine spirit of the Revolution, and Parent’s encyclopedic analysis, an

example of Enlightenment values of reason and science, embody these opposing

sides of the French dilemma regarding prostitution after the Revolution.

Much ink

and paint were utilized to address the problem in the 19th century through the

work of numerous writers and artists who brought the hazy subject of

prostitution into clearer focus. Yet the actual issue remains unresolved.

Hundreds of French words for “prostitute” indicate that the popular preference

(at least for men) was the boudoir; art and literature, ditto. But for women,

the choice was not quite so clear. Denied access to many of the rights promised

by the Revolution, including education and gainful employment, many women had

no alternative except the boudoir. It might have been a choice, but it was one

of last resort and all the synonyms for prostitute — whether as ethereal as

nymphe or as sordid as salope — did not disguise the cruelty and misery that

lie beneath prostitution. These are the dismal facts to which Flaubert alluded

in his own honest admission of prostitution’s appeal. Parent claimed as much

nearly two decades earlier in the blunt style of a statistician: “Prostitutes

are as inevitable in any great aggregation of humanity as sewers, cesspits and

refuse dumps.” But perhaps we should hear not from the boudoir, but from the

church, from someone whose virtue is undeniable, yet who understood the

necessity of some forms of vice, for it was Saint Augustine who warned: “Remove

prostitutes from human affairs, and licentiousness will overthrow society.” And

so, at the least, we must acknowledge the perenniality of prostitutes and cease

to vilify or scorn them while ignoring the men who create their ranks. And we

must certainly give thanks to all the pavement nymphes and roadside flowers,

all the lorettes and grisettes, all the kept women and courtesans for all the

art and literature they have inspired. For this alone, they deserve our respect

and reverence — but for their ability to survive pain, privation, degradation,

and misery, they deserve our awe.

Pavement

Nymphs and Roadside Flowers: Prostitutes in Paris After the Revolution. By Victoria Dailey. Los Angeles Review of Books,

March 1, 2019.

The star’s

moment should be triumphant. She’s brilliantly lit, her leg lifted in a

graceful ballet pose, and she’s clearly the star of the show. But in the wings

lurks a black-clad figure—a symbol for the sordid backstage reality of the

ballerina.

It’s not

clear who Edgar Degas used as the model for the 1879 painting, L’Etoile, that

depicts that tense moment. But it’s likely that she was a prostitute. Sex work

was part of ballerinas’ realities during the 19th century, an era in which

money, power and prostitution mingled in the glamorous and not-so-glamorous

backstage world of the Paris Opera.

The Paris

Opera Ballet, founded in the 17th century, was the world’s first professional

ballet company, and continues as one of the preeminent outfits today. Throughout

the 19th century, it raised the bar for dance—but on the backs of many

exploited young women.

Women

entered the ballet as young children, training at the opera’s dance school

until they could snag a coveted position in the corps de ballet. Girls who

studied at the school became apprentices to the Opera; only after years of

militaristic training and a series of brutal exams could they get guaranteed,

long-term contracts.

In the

meantime, they attended classes and auditioned for small, walk-on roles. Often

malnourished and dressed in hand-me-downs, the “petits rats” of the ballet were

vulnerable to social and sexual exploitation. And the wealthy male subscribers

of the Paris Opera—nicknamed abbonés—were often on hand to exploit them.

“The ballet

is…what the bar-room is to many a large hotel,”wrote Scribner’s Magazine in

1892, “the chief paying factor, the one from which the surplus profits come.”

Men subscribed to the opera not for the music, but for the beautiful ballerinas

who danced twice per show—and, behind the scenes, they bought sexual favors from

the women they ogled on stage.

The abonnés

were so powerful, they were part of the Opera’s very architecture: When Charles

Garnier designed his iconic opera house in the 1860s, he included a special

separate entrance for season ticket holders. The building also included a

lavish room called the foyer de la danse. Located directly behind the stage, it

was a place where ballet dancers could warm up and practice their moves before

and during performances. But it was designed with male patrons, not dancers, in

mind. The foyer was a place for them to socialize with—and proposition—ballet

dancers.

At the

time, women’s bodies were typically covered by lots of clothing. In contrast,

ballet dancers wore skimpy and revealing outfits (though ballet costumes of the

time, which included skirts, were much less form-fitting than today’s leotards

and tights). Subscribers could, and did, go backstage to ogle women. Due to

their social status, they were free to socialize with them, too.

“Epic

scenes took place backstage,” wrote the Comte de Maugny, who described the

foyer de la danse as a kind of meat market. For subscribers, backstage was a

kind of men’s club where they could meet and greet other power brokers, make

business deals and bask in a highly sexualized atmosphere.

For

dancers, though, it was a place where they were subject to scrutiny and harassment.

Dancers were expected to submit to the attentions and affections of

subscribers,most of whom were nobleman and important financiers and whose money

underwrote the majority of the opera’s operations.

Since

subscribers were so powerful, they could influence who made it into coveted

roles and who was fired from the ballet. They could lift a girl out of poverty

by becoming her “patron,” or client, setting her up in comfortable quarters and

paying for private lessons that could increase her cachet in the ballet. Often,

girls’ own mothers—who acted not unlike entertainment agents today—helped set

up and maintain these relationships. For many Paris Opera ballerinas from poor

backgrounds, a relationship with a rich man was their only chance at stability.

Some

dancers managed to advance without a rich patron, becoming celebrities on the

merits of their own abilities, notes historian Lorraine Coons. But even those

dancers who did succeed independently were looked down on as suspected

prostitutes.

One

influential Parisian couldn’t afford the expensive subscription that allowed

special access to ballerinas: Impressionist painter Edgar Degas. During the

1870s and 1880s, he produced hundreds of drawings and paintings of Paris Opera

dancers, relying on his friends tosecure backstage passes so he could sketch

the dancers in their habitat. There, he recorded behind-the-scenes views of

dancers practicing—and captured glimpses of the world of the lecherous male

subscribers, too.

One of

Degas’ best-known works is his Little Dancer of Fourteen Years, a life-sized

statue of a teenage “petit rat,” or ballet dancer in training. To modern eyes,

it’s the portrait of a child who eagerly awaits her next dance step. But when

Degas exhibited it in 1881, it was panned by the critics, who called the dancer

“frightfully ugly,” monkey-like, and “marked by the hateful promise of every

vice.”

Degas’

subject may have been vulnerable, but for 19th-century observers, she was

marked by the sordidness of the sexual harassment that was baked into ballet.

Teenager Marie van Goethem, a Paris Opera petit rat who modeled for the

sculpture, likely traded sex for money in order to survive—but even if she

hadn’t, it’s almost certain Degas’ audience would have assumed she did.

Sexual

Exploitation Was the Norm for 19th Century Ballerinas. By Erin Blackmore. History , August 22, 2018.

An hour

with a prostitute costs on average $150, though prices can range from as low as

$5 for a single sex act to $1,000 an hour, the going rate for “high-end” online

escort services in Miami. Many of those in the sex trade were encouraged by

family members to take up sex work. Pimps rely as much if not more on emotional

manipulation than physical violence to control their sex workers.

These are

some of the findings of a recently released study by the Urban Institute

describing the structure of the underground commercial sexual economy—street

and Internet prostitution, escort services, massage parlors, brothels, and

child pornography—in eight major cities across the U.S. Funded by the National

Institute of Justice, the report is unprecedented in its scope and depth: It

will surely change how both lawmakers and law enforcers think about the sex

trade and shape their approaches to control it.

Trying to

understand the underground sex economy, however, is as old as police work

itself. One of the very first police forces in the Western world emerged in

18th-century Paris, and one of its vice units asked many of the same questions

as the Urban Institute authors: How much do sex workers earn? Why do they turn

to sex work in the first place? What are their relationships with their

employers?

And yet,

unlike the Urban Institute researchers, who undertook their study in the hope

that a better understanding of how this underground economy functions might

lead to better public policy, this Parisian vice unit had more nebulous

motives. Its inspectors compiled vast dossiers of information on the city’s

elite sex workers and their patrons. But they rarely acted on that information.

To this day, it remains a mystery why the Parisian police spent so much time

and effort observing an underground economy it apparently had no interest in

curtailing. But their files are an historian’s dream. They paint a vivid

portrait of 18th-century Parisian life and offer a particularly fascinating

view of the city’s elite sex workers, who had greater social mobility than most

women in that period.

The focus

of this particular vice unit was the demimonde, the world of elite

prostitution. The policing of street prostitution and brothels that catered to

men of little means were left to other police personnel, who were far more

aggressive in their tactics. They apprehended street prostitutes and those who

worked in taverns. They raided and shut down brothels, bringing all those

arrested women—prostitutes and petty madams alike—to police court where they

were tried en masse and then taken, heads shaved, to serve time in Paris’

famous women’s prison, La Salpêtrière.

Elite

prostitution was treated differently. Certain brothels that catered to the male

elite were allowed to operate. It was one duty of the vice unit’s inspectors to

make sure the madams of these “authorized” brothels abided by certain rules,

one of which was to supply the inspectors with a steady stream of information.

But most of the unit’s energy was spent watching a particular group of elite

prostitutes that worked as professional mistresses. Called kept women (the

French term is dames entretenues), these women (and girls) provided sex,

company, and sometimes even love for elite men in exchange for being “kept,”

financially supported so that they could establish and maintain a household. La

galanterie, the practice of being or keeping a mistress, was not illegal, even

while prostitution was.

The vice

unit, which operated from 1747 to 1771, turned out thousands of hand-written

pages detailing what these dames entretenues did. Being kept in the 18th

century was not a profession in the modern sense of the term, but it was a job.

What was sold was standardized: sex, company, the pretense of affection, and

usually the illusion that the patron was the center of the mistress’s world.

Kept women had oral contracts with their patrons, which stipulated how much the

mistress would be paid each month, and whether the patron would set his

mistress up in an apartment, buy her new furnishings, pay her bills, and give

her gifts. The mistress’ duties were not delineated but rather were

“understood,” leaving a great deal of room for misunderstanding.

In

following kept women about Paris, the police, much like the authors of the

Urban Institute report, were interested in every aspect of these women’s

professional and personal lives, from their entry into sex work to the intimate

details of their relationships with their patrons. They gathered biographical

and financial data on the men who hired kept women—princes, peers of the realm,

army officers, financiers, and their sons, a veritable “who’s who” of high

society, or le monde. Assembling all of this information required cultivating

extensive spy networks. Making it intelligible required certain bureaucratic

developments: These inspectors perfected the genre of the report and the

information management system of the dossier. These forms of “police writing,”

as one scholar has described them, had been emerging for a while. But they took

a giant leap forward at midcentury, with the work of several Paris police inspectors,

including Inspector Jean-Baptiste Meusnier, the officer in charge of this vice

unit from its inception until 1759. Meusnier and his successor also had clear

literary talent; the reports are extremely well written, replete with irony,

clever turns of phrase, and even narrative tension—at times, they read like

novels.

Here is an

example. In 1752, Inspector Meusnier wrote a report about a woman named

Demoiselle Blanchefort. It was the first of at least 20 that came to make up

her file, covering more than a decade of her life in elite sex work. The first

report was a sort of back history, which the inspector tried to assemble on

most of his subjects. It explained how the subject under surveillance came to

be an elite prostitute. Blanchefort, Meusnier wrote, was the daughter of a

surgeon in Angers, a city in western France. Surgeon in this period was not yet

a high-status profession. It was closer to the artisan than the professional,

still linked in popular thinking with barber—the red and white strips of the

barber’s pole represented the blood and bandages once associated with the

trade. Blanchefort, like most kept women, was from the lower middle of the

social spectrum. The inspector did not seem to know her real name, or how or

why she came to Paris, but he was able to trace her once she became an elite

sex worker at the brothel of Madam Carlier, where she took the name “Victoire.”

Victoire was not a virgin, claimed Meusnier. Brothels were not supposed to take

virgins as workers, though they often did and with police cognizance. The

report, as with most reports, justified why it was permissible, in the state’s

eyes, for Blanchefort to be a prostitute. Her virginity gone, she was “ruined,”

theoretically unfit for marriage.

Meusnier

goes on: At Carlier’s, Blanchefort met an army officer who pulled her out of

the brothel to set her up as his mistress. This was a common practice;

customers often met their future mistresses at these establishments. To take

Blanchefort, the army officer had to pay all of her debts, which could be

significant. Debt was one way the madams bound sex workers to them, compelling

them to stay in the brothels to work. Some workers arrived with debt the madams

assumed. Others borrowed money from the madams to pay for their food and

clothing and particularly for medical care, the cost of which could easily

exceed a prostitute’s earnings.

After a

two-year break, Meusnier returned to the dossier of Demoiselle Blanchefort. Her

fortunes had changed, greatly. She now called herself Varenne (the constant

name changes are one of the challenges facing the police, and scholars trying

to reconstruct this world centuries later). In two short paragraphs, Meusnier

caught his files up to date. Varenne had had a number of wealthy patrons and

the cumulative result of their benefaction was her “perfectly furnished”

apartment in the Marais section of Paris. The term “perfectly furnished”

indicated that Varenne had made it in the demimonde. She possessed not only

furniture of necessity such as a bed and table, but also those of display and

various objects d’art. The furniture would have been of the best quality,

stylish and expensive. Kept women were obsessed with furnishings. As the

historian Kathryn Norberg argues, their possessions distinguished these sex

workers from streetwalkers, by defining a home and suggesting permanence. Given

their extraordinary cost, furnishings were also a form of capital acquisition

and functioned as status symbols. Varenne’s furnishings (as well as her jewelry

and clothes) represented the value other elite men placed on her services,

making her a more expensive commodity in the subculture of the demimonde. This

sort of financial mobility and wealth acquisition was unheard of for women from

such backgrounds. Had Varenne stayed in Angers, the most she could have

expected was to marry a man in her father’s profession, or one who had a

similar social status.

Over the

next eight years, Meusnier and his successor, Inspector Louis Marais, charted

Varenne’s career. Marais’ final report, dated Feb. 26, 1762 found Varenne,

after a decade of sex work, now in possession of significant wealth for someone

of her background and on the verge of marrying her boyfriend, who was an army

officer and a noble. She was stealing from her patron to pay for the nuptials.

Did the marriage go through? The inspectors hoped it would not, fearing the social

destruction of the officer. If it had, it would have represented a significant

jump in social status for Varenne. But the real question is why did the police