Centuries ago, mysterious sea serpents and mermaids were believed to be hidden in the world's vast oceans. Merfolk (mermaids and mermen) are, of course, the marine version of half-human, half-animal legends that have captured human imagination for ages. One source, the "Arabian Nights," described mermaids as having "moon faces and hair like a woman's but their hands and feet were in their bellies and they had tails like fishes," Charles J.S Thompson, a former curator at the Royal College of Surgeons of England, notes in his in his book "The Mystery and Lore of Monsters” (Kessinger Publishing, 2010). Thompson writes that "traditions concerning creatures half-human and half-fish in form have existed for thousands of years, and the Babylonian deity Era or Oannes, the Fish-god ... is usually depicted as having a bearded head with a crown and a body like a man, but from the waist downwards he has the shape of a fish."

Greek mythology contains stories of the god Triton, the merman messenger of the sea, and several modern religions including Hinduism and Candomble (an Afro-Brazilian belief) worship mermaid goddesses to this day. One of the earliest depictions of a mermaid came from Syrian mythology. Atargatis, also known as Derceto or the Syrian goddess, was half woman half fish deity of the ancient city Hierapolis-Bambyce in Syria.

However, many people are perhaps most familiar with the Disney version of "The Little Mermaid," a somewhat sanitized version of a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale first published in 1837. In some legends from Scotland and Wales mermaids befriended — and even married — humans. Meri Lao, in her book "Seduction and the Secret Power of Women “ notes that "In the Shetland Islands, mermaids are stunningly beautiful women who live under the sea; their hybrid appearance is temporary, the effect being achieved by donning the skin of a fish. They must be very careful not to lose this while wandering about on land, because without it they would be unable to return to their underwater realm."

In folklore, mermaids were often associated with misfortune and death, luring errant sailors off course and even onto rocky shoals, according to the Ohio State University.

Though not as well known as their female counterparts, mermen have an equally fierce reputation for summoning storms, sinking ships and drowning sailors. One especially feared group, the Blue Men of the Minch, are said to dwell in the Outer Hebrides off the coast of Scotland, according to The Scotsman. They look like ordinary men (from the waist up anyway) with the exception of their blue-tinted skin and gray beards. Local lore claims that before laying siege to a ship, the Blue Men often challenge its captain to a rhyming contest; if the captain is quick enough of wit and agile enough of tongue he can best the Blue Men and save his sailors from a watery grave.

Japanese legends have a version of merfolk called kappa. Said to reside in Japanese lakes, coasts and rivers, these child-size water spirits appear more animal than human, with simian faces and tortoise shells on their backs, according to Encyclopaedia Britannica. Like the Blue Men, the kappa sometimes interact with humans and challenge them to games of skill in which the penalty for losing is death. Kappa are said to have an appetite for children and those foolish enough to swim alone in remote places — but they especially prize fresh cucumbers.

Throughout West, South and Central Africa, the mythical water spirit called Mami Wata, which means “Mother of the Waters”, was once worshipped for their ability to bestow beauty, health and wisdom to their followers, according to the Royal Museums Greenwich. Mami Wata is often portrayed as a mermaid or snake charmer, however, her appearance has been influenced by presentations of other indigenous African water spriest as well as European mermaids and Hindu gods and goddesses, according to the Smithsonian.

The reality of mermaids was assumed during mediaeval times, when they were depicted matter-of-factly alongside known aquatic animals such as whales. Hundreds of years ago sailors and residents in coastal towns around the world told of encountering the sea maidens. One story dating back to the 1600s claimed that a mermaid had entered Holland through a dike, and was injured in the process. She was taken to a nearby lake and soon nursed back to health. She eventually became a productive citizen, learning to speak Dutch, perform household chores, and eventually converted to Catholicism, according to The Flying Dutchman and Other Folktales from the Netherlands by Theo Meder.

Another mermaid encounter once offered as a true story is described in Edward Snow's "Incredible Mysteries and Legends of the Sea." A sea captain off the coast of Newfoundland described his 1614 encounter: "Captain John Smith [of Jamestown fame] saw a mermaid 'swimming about with all possible grace.' He pictured her as having large eyes, a finely shaped nose that was 'somewhat short, and well-formed ears' that were rather too long. Smith goes on to say that 'her long green hair imparted to her an original character that was by no means unattractive.'" In fact Smith was so taken with this lovely woman that he began "to experience the first effects of love" as he gazed at her before his sudden (and surely profoundly disappointing) realization that she was a fish from the waist down. Surrealist painter Rene Magritte depicted a sort of reverse mermaid in his 1949 painting "The Collective Invention."

By the 1800s, hoaxers churned out faked mermaids by the dozen to satisfy the public's interest in the creatures. The great showman P.T. Barnum displayed the "Feejee Mermaid" in the 1840s and it became one of his most popular attractions. Those paying 50 cents hoping to see a long-limbed, fish-tailed beauty comb her hair were surely disappointed; instead they saw a grotesque fake corpse a few feet long. It had the torso, head and limbs of a monkey and the bottom part of a fish. To modern eyes it was an obvious fake, but it fooled and intrigued many at the time.

The concept of aquatic humans was taken more seriously in 1960 when British Biologist Sir Alister Hardy proposed a new theory to explain some of the anomalies of human evolution. Our lack of fur, big brains and subcutaneous fat (qualities seen in marine mammals) are just some traits that lead Hardy to propose that humans descended not from Savannah dwelling apes, but more marine environments. Hardy and supporters of his aquatic ape theory(opens in new tab) suggest that humans took to the water to find food instead of land and eventually evolved to live in the water, which many have used to perpetuate the idea of mermaid existence, according to Ohio State University(opens in new tab). Hardy's theory remains largely controversial and lacking in evidence. The majority of archaeological evidence supports a human evolution that occurred on land rather than in the water.

Could there be a scientific basis for the mermaid stories? Some researchers believe that sightings of human-size ocean animals such as manatees and dugongs might have inspired merfolk legends. These animals have a flat, mermaid-like tail and two flippers that resemble stubby arms. They don't look exactly like a typical mermaid or merman, of course, but many sightings were from quite a distance away, and being mostly submerged in water and waves only parts of their bodies were visible. Identifying animals in water is inherently problematic, since eyewitnesses by definition are only seeing a small part of the creature. When you add in the factor of low light at sunset and the distances involved, positively identifying even a known creature can be very difficult. A glimpse of a head, arm, or tail just before it dives under the waves might have spawned some mermaid reports.

Modern mermaid reports are very rare, but they do occur; for example, news reports in 2009 claimed that a mermaid had sighted off the coast of Israel in the town of Kiryat Yam. It (or she) performed a few tricks for onlookers just before sunset, then disappearing for the night. One of the first people to see the mermaid, Shlomo Cohen, said, "I was with friends when suddenly we saw a woman laying on the sand in a weird way. At first I thought she was just another sunbather, but when we approached she jumped into the water and disappeared. We were all in shock because we saw she had a tail." The town's tourism board was delighted with their newfound fame and offered a $1 million reward for the first person to photograph the creature. Unfortunately the reports vanished almost as quickly as they surfaced, and no one ever claimed the reward.

In 2012 an Animal Planet special, "Mermaids: The Body Found," renewed interest in mermaids. It presented the story of scientists finding proof of real mermaids in the oceans. It was fiction but presented in a fake-documentary format that seemed realistic. The show was so convincing that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration received enough inquiries following the TV special that they issued a statement officially denying the existence of mermaids.

A temple in Fukuoka, Japan, is said to house the remains of a mermaid that washed ashore in 1222, according to the Smithsonian. Its bones were preserved at the behest of a priest who believed the creature had come from the legendary palace of a dragon god at the bottom of the ocean. For nearly 800 years the bones have been displayed, and water used to soak the bones was said to prevent diseases. Only a few of the bones remain, and since they have not been scientifically tested, their true nature remains unknown.

Mermaids may be ancient, but they are still with us in many forms; their images can be found all around us in films, books, Disney movies, at Starbucks — and maybe even in the ocean waves if we look close enough.

Mermaids & mermen: Facts & legends. By Benjamin Radford, Scott Dutfield. Live Science, February 14, 2022.

The above examples are quite representative of what an early modern Briton would have found in the newspapers. That these interactions were even reported tells us much. Intelligent men like Benjamin Franklin considered such encounters legitimate enough to spend the time and money to print in their widely read newspapers. By doing so, printers and authors helped sustain a narrative of curiosity surrounding these wondrous creatures. As a Londoner sat down with his paper (perhaps in the aptly named Mermaid Tavern) and read of yet another instance of a mermaid or triton sighting, his doubt might have transformed into curiosity.

Philosophers’ debates over mermaids and tritons in this period reveal their willingness to embrace wonder in their larger quest to understand the origins of humankind. Naturalists used a wide range of methodologies to critically study these odd hybrids and, in turn, assert the reality of merpeople as evidence of humanity’s aquatic roots. As with other creatures they encountered in their global travels, European philosophers utilized various theories — including those of racial, biological, taxonomical, and geographic difference — to understand merpeople’s and, by proxy, humans’ place in the natural world.

Westerners’ combination of curiosity and imperial expansion is well reflected in the cultural relevance of merpeople. Wealthy individuals and philosophical societies funded naturalists’, botanists’, and cartographers’ expeditions to the New World in the hope that they might broaden humanity’s understanding of the world and their place in it. In an expanding number of investigations into mermaids and tritons, naturalists demonstrated a growing penchant for the wondrous. They also, importantly, revealed how the process of scientific research had drastically changed over the last two hundred years. Rather than relying strictly on ancient texts and hearsay, eighteenth-century naturalists mustered various “modern” resources — global correspondence networks, erudite publication opportunities, transatlantic travel, specimen procedures, and learned societies — to rationally examine what many considered fantastical. Thus, a growing body of gentlemen both carried on and eschewed the supposed narrative of enlightened logic by applying well-known, valid research methods to mysterious merpeople. In doing so, eighteenth-century philosophers such as Cotton Mather, Peter Collinson, Samuel Fallours, Carl Linnaeus, and Hans Sloane complicated our — and their contemporaries’ — conceptions of science, nature, and humanity. The smartest men in the Western world, in short, spent much of the eighteenth century chasing merpeople around the globe.

The Royal Society of London proved key in this endeavour, acting as both a repository and producer of legitimate scientific investigation. Sir Robert Sibbald, a respected Scottish physician and geographer, well understood the Society’s desire for ground-breaking research. On November 29, 1703 he wrote to Sir Hans Sloane, the president of the Society, to inform the London gentleman that Sibbald and his colleagues had been recording an account of Scotland’s amphibious creatures, along with accompanying copper-plate images, which he hoped to dedicate to the Royal Society. Realizing the Society’s interest in the most up-to-date studies, Sibbald told Sloane that he had “added several accounts and the figures of some Amphibious Aquatic Animals, and of some of mixed Kinds, as the Mermaids or Syrens seen sometimes in our Seas”.5 Here were two leading thinkers of the eighteenth century exchanging erudite missives on merpeople.

On July 5, 1716, Cotton Mather also penned a letter to the Royal Society of London. This was not odd, as the Boston naturalist often detailed his scientific findings. Yet this letter’s subject was somewhat curious — titled “a Triton”, the missive demonstrated Mather’s sincere belief in the existence of merpeople. The Royal Society of London fellow began by explaining that, until recently, he considered merpeople no more real than “centaurs or sphynxes”. Mather found myriad historical accounts of merpeople, ranging from the ancient Greek Demostratus, who witnessed a “Dried Triton . . . at ye Town of Tanagra”, to Pliny the Elder’s assertions of mermaids and tritons’ existence. Yet because “Plinyisums are of no great Reputation in our Dayes”, Mather noted, he passed off much of these ancient accounts as false. Mather’s “suspicions” of the existence of such creatures “had got more Strength given”, however, when he read sundry ancient accounts via well-respected European thinkers like Boaistuau and Bellonius.

Still, Mather was not totally convinced, at least until February 22, 1716, when “three honest and credible men, coming in a boat from Milford to Brainford (Connecticut)”, encountered a triton. Having heard this news at first hand, Mather could only exclaim, “now at last my credulity is entirely conquered, and I am compelled now to believe the existence of a triton”. As the creature fled the men, “they had a full view of him and saw his head, and face, and neck, and shoulders, and arms, and elbows, and breast, and back all of a human shape . . . [the] lower parts were those of a fish, and colored like a mackerel”. Though this “triton” escaped, it convinced Mather of merpeople’s existence. Maintaining that his story was not false, Mather promised the Royal Society that he would continue to relay “all New occurrences of Nature”.

The famous naturalist Carl Linnaeus also threw himself into investigating mermaids and tritons. Having read newspaper articles detailing mermaid sightings in Nyköping, Sweden, Linnaeus sent a letter to the Swedish Academy of Science in 1749 urging a hunt in which to “catch this animal alive or preserved in spirits”. Linnaeus admitted, “science does not have a certain answer of if the existence of mermaids is a fact or is a fable or imagination of some ocean fish”. Yet in his mind, the reward outweighed the risk, as the discovery of such a rare phenomenon “could result in one of the biggest discoveries that the Academy could possibly achieve and for which the whole world should thank the Academy”. Perhaps these creatures could reveal humankind’s origins? For Linnaeus — world-renowned for his contributions to taxonomical classification — this ancient mystery must be solved.

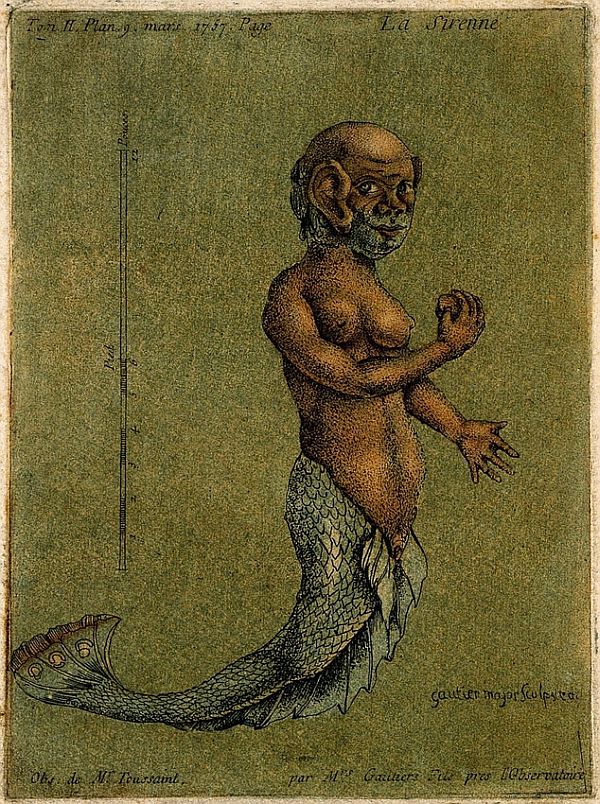

The Dutch artist Samuel Fallours also claimed to have discovered merpeople in a distant land, and in doing so set off a decades-long debate that spanned continents and media types. Fallours lived in Ambon, Indonesia, from 1706 to 1712 while serving as a clergy’s assistant for the Dutch East India Company. During Fallours’ tenure on a “Spice Island”, he drew various representations of native flora and fauna. One image happened to depict a mermaid, or “sirenne”. Fallours’ “sirenne” closely resembled the classic depiction of a mermaid, with long, sea-green hair, a pleasant face and a bare midsection that turned into a blue/green tail at the waist. This mermaid’ s skin, however, was dark (with a slight greenish tinge), implying a similarity with the local indigenous population.

In the notes that accompanied Fallours’ original drawing, the Dutch artist contended that he “had this Syrene alive for four days in my house at Ambon in a tub of water”. Fallours’ son had brought it to him from the nearby island of Buru “where he purchased it from the blacks for two ells of cloth”. Eventually, the whimpering creature died of hunger, “not wishing to take any nourishment, neither fishes nor shell fishes, nor mosses or grasses”. After the mermaid’s death, Fallours “had the curiosity to lift its fins in front and in back and [found] it was shaped like a woman”. Fallours claimed that the specimen was subsequently relayed to Holland and lost. The story of this Ambon siren, however, had only just begun.

Years before Louis Renard, a French-born book dealer living in Amsterdam, even published a version of Fallours’ “sirenne” in his own Poissons, ecrevisses et crabes (1719), Fallours’ images had already enjoyed wide distribution. Yet, because of the unusually bright colours and fantastic creatures represented in Fallours’ drawings, many doubted their accuracy and veracity. Renard was especially worried about the validity of Fallours’ sirenne, exclaiming, “I am even afraid the monster represented under the name of mermaid . . . needs to be rectified.”

Philosophers found both promise and disgust in Fallours’ painting and the subsequent dialogue that Renard initiated with his letters. In his preface to the 1754 version of Renard’s Poissons, ecrevisses et crabes, the Dutch collector and director of the menageries and “Natuur-en Kunstcabinetten des Stadhouders” Aernout Vosmaer called objections to merpeople’s reality “weak”, and contended that “this monster, if we must call it by this name (although I do not see the reason for it)” was simply able to avoid humans’ traps better than any other creature (because of its hybrid nature) and was thus rarely seen. Because of merpeople’s biological similarity to humans, furthermore, Vosmaer argued that they were “more subject to decay after death than the body of other fishes”. Such a lack of preservation not only diminished sightings, it also went towards explaining the lack of full specimens in cabinets of curiosities.

By the mid-eighteenth century, a growing number of physicians not only believed in the existence of merpeople, but also began to wonder what sort of ramifications such creatures might have for understanding humanity’s origins and future. As G. Robinson noted in The Beauties of Nature and Art Displayed in a Tour Through the World (1764), “though the generality of natural historians regard mermen and mermaids as fabulous animals . . . as far as the testimony of many writers for the reality of such creatures may be depended upon, so much reason there appears for believing their existence.” The Reverend Thomas Smith took Robinson’s contention to an even more definitive note four years later, asserting that while “there are many persons indeed who doubt the reality of mermen and mermaids . . . yet there seems to be sufficient testimony to establish it beyond dispute”. But the problem remained: men like Robinson and Smith could rely only upon ancient, often ridiculed sightings or tenuous hypotheses for their “proof”. They needed scientific research to back up their claims, and they got it.

Two especially important articles — each approaching merpeople through unique scientific methodology — appeared in the Gentleman’s Magazine between 1759 and 1775. The first piece, published in December 1759, accompanied a plate image of a “Syren, or Mermaid . . . said to have been shewn in the fair of St Germains [Paris]” in 1758. The author noted that this siren was “drawn from life . . . by the celebrated Sieur Gautier”. Jacques-Fabien Gautier, a French printer and member of the Dijon Academy, was widely recognized for his skill in printing accurate images of scientific subjects. Attaching Gautier’s name to the print garnered immediate credibility, even for such a strange image; but even without Gautier’s name attached to it, the print and its accompanying text were distinguished by their modern scientific methodology. Gautier had apparently interacted with the living creature, finding that it was “about two feet long, alive, and very active, sporting about in the vessel of water in which it was kept with great seeming delight and agility”.

Gautier consequently recorded that “its positions, when it was at rest, was always erect. It was a female, and the features were hideously ugly”. As displayed in detail by the accompanying print, Gautier found its skin “harsh, the ears very large, and the back-parts and tail were covered with scales”. According to the image, this was not the mermaid that had long graced cathedrals throughout Europe. Nor did it match the description relayed by so many other naturalists and discoverers throughout history. Where most had seen a striking female form, distinguished by flowing blue-green hair, Gautier’s mermaid was completely bald with “very large” ears and “hideously ugly” features. Gautier’s siren was also much smaller than traditional mermaids at only sixty centimetres (two feet) tall. More than anything, Gautier’s mermaid reflected the mid-eighteenth-century approach to studying the wondrous aspects of nature: the Frenchman employed well-respected scientific techniques — in this case a close inspection of the creature’s anatomy and an accurate accompanying drawing (much resembling those of other illustrated creatures at the time) — to display as reality what many still considered fantasy.

Scholars used the Gautier publication to reflect upon the legitimacy of merpeople. An anonymous contributor to the June 1762 issue of the Gentleman’s Magazine exclaimed that Gautier’s image “seems to establish the fact incontrovertibly, that such monsters do exist in nature”. But this author had further evidence. An April 1762 edition of the Mercure de France reported that in June the previous year two girls playing on a beach on the island of Noirmoutier (just off the southwest coast of France) “discovered, in a kind of natural grotto, an animal of a human form, leaning on its hands”. In a rather morbid turn of events, one of the girls stabbed the creature with a knife and watched as it “groaned like a human person”. The two girls then proceeded to cut off the poor creature’s hands “which had fingers and nails quite formed, with webs between the fingers”, and sought the aid of the island’s surgeon, who, upon seeing the creature, recorded:

“it was as big as the largest man . . . its skin was white, resembling that of a drowned person . . . it had the breasts of a full-chested woman; a flat nose; a large mouth; the chin adorned with a kind of beard, formed of fine shells; and over the whole body, tufts of similar white shells. It had the tail of a fish, and at the extremity of it a kind of feet. Such a story — when verified by a trained and trusted surgeon — only further proved Gautier’s research. For a growing number of eighteenth-century Britons, merpeople existed, bore a striking resemblance to humans, and needed to be studied at length.”

In May 1775 the Gentleman’s Magazine published an account of a mermaid “taken in the Gulph of Stanchio, in the Archipelago or Aegean Sea, by a merchantman trading to Natolia” in August 1774. Like Gautier’s 1759 “syren”, this specimen was drawn and described in detail. Yet the author also distanced himself from Gautier, noting that his mermaid “differs materially from that shewn at the fair of St Germaine, some years ago”. In an especially interesting turn of events, the author utilized a comparison of the two mermaid prints to speculate on issues of race and biology, contending that “there is reason to believe, that there are two distinct genera, or, more properly, two species of the same genus, the one resembling the African blacks, the other the European whites”. While Gautier’s siren “had, in every respect, the countenance of a Negro”, the author found that his mermaid displayed “the features and complexion of an European. Its face is like that of a young female; its eyes a fine light blue; its nose small and handsome; its mouth small; its lips thin”.

Early modern English writers leaned on two stereotypes to commodify and denigrate African female bodies, as the historian Jennifer L. Morgan has shown. First, they “conventionally set the black female figure against one that was white — and thus beautiful”. Here this 1775 author follows perfectly in line, comparing Gautier’s “Negro” and “hideously ugly” mermaid to his own beautiful mermaid with the “features and complexion of an European”. Second, early modern Europeans concentrated on African women’s supposed “sexually and reproductively bound savagery” in order to ultimately turn to “black women as evidence of a cultural inferiority that ultimately became encoded as racial difference”. Not only were naturalists using the science of merpeople to gain a deeper understanding of the natural order of sea creatures, they were also utilizing their interpretations of these mysterious beings to reflect upon humans’ — especially white humans’ — place in an ever-changing racial, biological framework.

Carl Linnaeus and his student Abraham Osterdam further complicated the narrative of classification and legitimacy. Though the Swedish Academy found nothing in their search for Linnaeus’ mermaid in 1749, Linnaeus and Osterdam took matters into their own hands by publishing a dissertation on the Siren lacertina (The Lizard Siren) in 1766. Having detailed a long list of mermaid sightings throughout history in the initial pages of this dissertation, they next relayed myriad instances of “marvelous animals and amphibians” that closely resembled creatures of lore and, consequently, made classification tricky. Ultimately, they judged this mermaid-like creature “worthy of an animal, which should be shown to those who are curious, because it is a new form”. The “father of classification” had apparently discovered a “worthy” piece of the natural puzzle, and it linked humans (even if distantly) to animals of the sea. The Siren lacertina also, importantly, further blurred the lines of classification that Linnaeus had so proudly developed, suggesting that perhaps human beings might find some distant relation to amphibious creatures.

Eighteenth-century philosophers’ investigations of merpeople represented both the endurance of wonder and the emergence of rational science during the Enlightenment period. Once resting at the core of myth and on the very fringes of scientific research, now mermaids and tritons were steadily catching philosophers’ attention. Initially such research was relegated to newspaper articles, brief mentions in travellers’ narratives, or hearsay, but by the second half of the eighteenth century, naturalists began to approach merpeople with modern scientific methodology, dissecting, preserving and drawing these mysterious creatures with the utmost rigour. By the close of the eighteenth century, mermaids and tritons emerged as some of the most useful specimens for understanding humanity’s marine origins. The possibility (or, for some, reality) of merpeople’s existence forced many philosophers to reconsider previous classification measures, racial parameters, and even evolutionary models. As more European thinkers believed — or at least entertained the possibility — that “such monsters do exist in nature”, Enlightenment philosophers merged the wondrous and rational to understand the natural world and humanity’s place in it.

Mermaids and Tritons in the Age of Reason. By Vaughn Scribner. Public Domain Review, September 29, 2021

Introduction

Mermaids reign as one of the most iconic mythological creatures of all time and fundamentally serve as a female archetype that resembles supernatural beauty and grace. The belief in mermaids spans across centuries, particularly originating from explorers’ reported sightings of these oceanic creatures. While sailing off the coast of Hispaniola in 1493, Christopher Columbus reports his Admirable seeing three mermaids or sirens. His logbook reads, “. . . as the Admirable was proceeding toward the Rio del Oro, he said that he had quite distinctly seen three Sirens emerging from the sea, but that they were not as beautiful as they are said to be, for their faces had some masculine traits.” Although the Admirable and other supposed eyewitnesses likely sighted manatees rather than mermaids, the logbook entry emphasizes a key component of the mermaids: beauty. Admittedly, one cannot expect a mermaid to appear beautiful if she is actually a manatee, but the Admirable’s notion that the sirens’ faces appear far less beautiful than imagined emphasizes the cultural association with merfolk as sexually alluring creatures. Unfortunately, folklore literature lacks an understanding behind the sexualization of Medieval mermaids in manuscripts, particularly in regard to the interactions between mermaids and mermen as mermen begin appearing alongside mermaids in Medieval manuscripts.

By analyzing images of mermaids and mermen from Medieval manuscripts, viewers can analyze the evolution of merfolk throughout Medieval manuscripts and understand how their sexuality and purpose shift overtime. Although mermaids originally exist as mythological creatures with un-emphasized hair and un-emphasized breasts, the presence of Medieval mermen causes Medieval mermaids to undergo a visual transformation that enhances their sexuality. Artists begin depicting mermaids with more voluminous hair and rounder, perkier breasts to accentuate their sexual biology and distinguish them from mermen. By further understanding this relationship between mermaids and mermen, viewers can use this relationship to consider the social relations between actual men and women during Medieval history. Thus, this study of Medieval merfolk provides readers with a fascinating perspective into the gender roles and social relationships between men and women during the time these images originate. These studies also reveal how iconic religious imagery such as the depictions of Adam and Eve with the serpent influence not only artistic imagery but universal social expectations and social norms. Ultimately, this paper explores the idealization of Medieval mermaids in the presence of Medieval mermen, particularly as Medieval mermaids develop sexualized appearances and embrace sinful roles as malevolent, cunning succubi with occult powers similar to lunar deities.

Terminology

In this paper, I use the term “mermaids” to describe merfolk who portray traditionally feminine characteristics such as long hair and visible breasts. I use the term “mermen” to describe merfolk who portray traditionally masculine characteristics such as short hair, pectoral muscles, broad shoulders, or beards. I use the term “siren” to refer to two different types of merfolk: female merfolk attacking men or luring sailors and female merfolk that display both fish-like characteristics and fish-like characteristics such as a fish tale with feathers, wings, or bird feet. I acknowledge that most Medieval sirens take the form of half bird-half human creatures with little to no merfolk or “fish” characteristics. However, this paper only focuses on “sirens” that display merfolk characteristics as well as bird characteristics. As a general term, I use “merfolk” to refer to mermaids, mermen, androgynous merfolk (merfolk with ambiguous sexual characteristics), and sirens.

Method of Analyzing Manuscript Images

In order to construct a narrative around the sexuality of Medieval merfolk and sirens, I consulted the Index of Medieval Art from Princeton University. Specifically, I searched the keyword “mermaid” between the dates 500 and 1500, and I specified the work of art type to “manuscripts,” which allowed me to analyze 61 images of merfolk from Medieval manuscripts. I also searched the keyword “merman” between the dates 500 and 1500, and I specified the work of art type to “manuscripts,” which allowed me to analyze 44 images of merfolk from Medieval manuscripts. I then searched the keyword “siren” between the dates 500 and 1500, and I specified the work of art type to “manuscripts,” which allowed me to analyze 123 images of sirens from Medieval manuscripts, with some overlap occurring as images from the “mermaid” and “merman” searches appeared in the “siren” search. Manuscript images of merfolk and sirens did not appear until the 900s, with the majority of images appearing between 1200 and 1500. Thus, I chose to focus my research on images of merfolk and sirens that appear in Medieval manuscripts dated between 1200 and 1500.

The Breasts of Medieval Mermaids

The sexuality of mermaids remains most apparent in the visibility of their breasts. Medieval mermaids lack the seashell bras that modern mermaids enjoy; instead, during the early depictions of Medieval merfolk and sirens, the bare breasts appear saggy and deflated. However, the breasts of merfolk and sirens receive less emphasis between 1250 and 1350. While the silhouette of the breast shape remains apparent, the contour of the breasts and detailing of the nipples remain faint. Later, from 1350 to 1500, Medieval artists depict merfolk and sirens with more idealized breasts. These breasts typically appear larger, rounder, perkier, and with greater nipple detailing . In other words, early depictions of Medieval mermaid breasts remain basic biological features of mythical female humanoids, while later depictions of Medieval mermaid breasts serve to enhance their sexuality.

The Chests of Medieval Mermen

While Medieval mermaids endure quite the transformation in the depictions of their chests, Medieval mermen fail to undergo the same level of transformation. Instead, Medieval mermen appear with flat pectoral muscles but no visible breasts. Unlike mermaids, many images of mermen also depict visible ribs underneath the chests of the mermen.

Depictions of Medieval Mermaid Motherhood

Medieval manuscripts depict mermaids and motherhood through two mediums: breastfeeding and birthing. In these depictions, motherhood appears as a solitary activity with no mermen present to provide parental support. Admittedly, depictions of Medieval mermaids engaging in maternal activities remain scarce. Mermen did not begin appearing regularly in Medieval manuscripts until 1400, so early artists lack exposure to the idea of merfolk as feminine and masculine; typically, one associates merfolk with mermaids as opposed to mermen. In other words, people generally consider mermaids to resemble a specific mythological female archetype as opposed to merfolk resembling an entire species with both feminine and masculine counterparts that can mate and produce offspring. So, early artists more commonly consider merfolk fantastical creatures as opposed to humanoids with children.

Even though fig. 5 showcases two double-tailed mermaids giving birth, two blue cloth garments conceal the breasts of the mermaids. This remains particularly fascinating since breasts exist for the biological purpose of providing newborn children with nutrients. So, this Medieval manuscript image seems like one of the primary instances where artists would expose the breasts due to the biological nature of the scene. Given that this image appears from 1270 to 1280, however, the mermaid fits appropriately into a period where Medieval manuscript artists had not begun emphasizing and idealizing breasts yet. Thus, the artist does not oversexualize the breasts, instead opting to emphasize their biological utility without putting them on display for decorative pleasure.

These images of Medieval mermaid motherhood also emphasize the variation in breast exposure that further accentuates the sexual transformation of breasts that Medieval mermaids endure. In fig. 6, the Medieval mermaid nurses her child with round, perky breasts. While the mermaid in fig. 6 covers her non-nursing breast with her arm, the mermaid in fig. 7 does not cover her non-nursing breast. Evidently, mermaids become more feminized and sexualized by having idealized breasts. Consequently, the breasts shift from solely providing biological utility to also invoking feminine sexuality.

The Hair of Medieval Mermaids

Medieval mermaids primarily appear with long hair. Early depictions of Medieval mermaids show long hair that is clearly visible but not accentuated. From 1300 to 1418, the hair appears short, hidden by a helmet or head covering of some sort, or obscured because the angles of the mermaids’ postures cause the hair to disappear down the backs of the mermaids . From 1418 to 1500, some artists begin depicting mermaids with deliberately longer hair again. Specifically, artists draw long, flowing hair and somewhat emphasize the visibility of the hair regardless of the angle of the merfolk; even forward-facing merfolk show accentuated hair that peers out from behind the mermaids’ backs.

Although mermaids experience a significant transformation regarding the presentation of their hair, the varying lengths of hair accentuate the mermaids’ cunning intellect. On the subject of mermaids’ hair, Krista Lauren Gilbert, a researcher from the Pacifica Graduate Institute and author of The Mermaid Archetype, writes:

“ If wielding hair can be equated to wielding a powerful weapon, then her weapon is double-edged and paradoxical. As both shield and blade, her hair simultaneously protects, incites, and ferociously attacks. As shield her hair acts as clothing in the realm of consciousness. Like Botticelli’s Venus emerging from the sea, her long tresses hold the numinous power selectively and protectively to conceal and reveal the beauty that lies beneath.”

In this sense, mermaids utilize their hair as weapons and tools for seducing onlookers. Mermaids may utilize their long hair to conceal their bodies, imitating coy façades as sailors gaze at their barely covered bodies in admiration and hunger for a glance at the flesh beneath the hair. Once mermaids earn the attention of sailors, the mermaids then brush their long hair back, fully revealing their exposed skin and breasts to completely entice the sailors. Consequently, the hair of the mermaids serves not only as an accentuation of feminine beauty but also as a tool for enticing and seducing onlookers. This idea endows mermaids, especially sirens, with cunning intelligence as they use their hair to manipulate onlookers.

The Clothing of Medieval Mermaids Medieval artists depict mermaids as primarily naked and exposing their breasts. Unlike their male counterparts, mermaids rarely wear cloth garments like shirts or hats. Even when standing next to an armored merman, mermaids lack clothing of their own. Evidently, the bodies of mermaids exist to emphasize and display their sexuality and femininity.

The Clothing of Medieval Mermen

Mermen primarily appear in Medieval manuscript images from 1400 to 1500. These images portray mermen as wearing much more clothing than mermaids typically in the form of cloth garments or armor. Specifically, mermen also wear hats more frequently than mermaids. Since artists begin depicting mermaids with longer hair to further accentuate their sexuality, the notion that mermen wear hats more frequently than mermaids further supports the idea that hair serves as a symbol of feminine sexuality. Consequently, mermen have short hair or wear headpieces to emphasize their masculinity. From 1450 to 1500, Medieval artists begin depicting mermen as wearing fewer clothes and exposing more skin. Interestingly, manuscript images primarily depict mermen naked when alone or in the presence of other mermen, but mermen rarely expose their bodies in the presence of mermaids. While a merman’s body exists to provide him with muscles and strength to wield weapons and fend off enemies, the mermaid’s body exists to attract viewers and emphasize the beauty within her that she so commonly embraces by looking into mirrors and combing her hair.

The Postures and Actions of Medieval Mermaids

In Medieval manuscripts from 1200 to 1400, artists depict mermaids completing a variety of different activities. Mermaids play musical instruments like horns and violas or engage in idle activity as they stand or “float” in space . In very rare cases, mermaids wield weaponry . However, female merfolk typically engage in action or violence when they appear as sirens. In these images, artists depict sirens as female merfolk biting off the heads of men or trying to lure sailors out to sea. Most importantly, mermaids look into mirrors and comb their hair. The mermaids holding the mirrors reflect the iconic imagery of Eve and the vanity she feels as she admires her own beauty . Additionally, the spherical shape of these mirrors alludes to moon disks worn by lunar deities, such as the Egyptian god of the moon, Khonsu. Therefore, these mirrors represent not only vanity but also the occult powers of sirens. In this sense, mermaids act as a somewhat evil feminine archetype. However, from 1400 to 1500, mermaids begin emitting more sexuality. Artists begin depicting Medieval mermaids as primarily looking in mirrors and combing their hair while disregarding previous actions, such as playing instruments or standing idle without emphasis. Later depictions of Medieval mermaids show not only mermaids combing their hair and looking in mirrors, but also mermaids raising their arms and exposing their breasts as though specifically posing to show off their bodies. Thus, later artists ensure that mermaids primarily exude sexuality given their sexually suggestive appearances.

In fig. 17, the serpent appears as a reflection of Eve’s face to emphasize Eve’s vanity. Since Eve vainly admired her own beauty and plucked the forbidden fruit, she bears responsibility for the fall of humanity and the association between women and vanity. In this sense, the mirror reflects the sins of the individual looking into the mirror. Consequently, Medieval artists depict mermaids as female archetypes looking into mirrors to reflect the sinful vanity of women and their responsibility for mankind’s sinful nature.

The Postures and Actions of Medieval Mermen

In the Medieval manuscripts, mermen typically complete three actions: playing musical instruments, standing idle with miscellaneous objects, and holding or utilizing weaponry in combat. Fundamentally, mermen engage in more masculine activities than their female counterparts. While mermen assert their masculinity by wearing armor, posing with weaponry, and engaging in combat, mermen also emphasize their masculinity by raising sticks over their heads. In various Medieval manuscripts, artists depict mermen as raising rod-like objects above their heads. These mermen hold these objects both alone and in the presence of mermaids, but mermaids do not hold these sticks above their heads. While some viewers may interpret these images as mermen holding miscellaneous objects without any significance, the presence of the rod enables the mermen to have a sexual presence due to the phallic shape of the stick.

The Postures and Actions of Medieval Mermaids and Mermen when Depicted Together

When depicted together in Medieval manuscripts, the gender roles of mermen and mermaids become most apparent. While mermaids initially start as more neutral figures with un-idealized breasts and un-emphasized or short hair, mermaids become much more sexualized and feminine when mermen start to appear more frequently in the 1400s. In the presence of mermen, mermaids almost solely comb their hair or look into mirrors while exposing their naked bodies due to a lack of clothing. On the other hand, mermen typically wear armor or hold weaponry in the presence of mermaids even when the image does not depict any sort of entity that the merman would fight. In other words, while some images of mermen will show the mermen fighting or holding weaponry, usually these mermen actively fight some sort of creature. However, when shown with mermaids, a lot of mermen still wear armor or hold weapons even with a lack of danger in the immediate area.39 So, in the presence of mermaids, mermen assert their masculinity by wearing clothing or armor and holding weapons. On the other hand, mermaids retain their femininity by combing their long hair or looking into mirrors and admiring their beauty while standing in a way that positions their bodies and their arms to expose their breasts (see fig. 22 and fig. 23)

These images have critical social implications for Medieval women during these periods. While Medieval scribes write these psalters, artists paint images unrelated to the text on the page. Thus, as Medieval readers read religious psalters, they witness these unrelated images of a naked mermaid or an armored jousting merman on the page. Consequently, readers must ask themselves to consider the purpose of these images and whether they provide any meaning to the texts themselves or instead images act like graffiti on the pages of these manuscripts. The idea that a man or woman could be sitting and reading a Medieval manuscript containing religious psalters but then glance to the side of the page and witness an image of a Medieval mermaid exposing her breasts and accentuating her sexuality feels particularly damning to the female population. Since the mermaids provide no significance to the text, the image of the mermaid makes women feel like decorative objects. While mermen randomly appear in heroic situations like wielding weaponry or engaging in combat, mermaids exist solely for viewing pleasure. Medieval women reading these psalters could not get inspired by the bravery and heroism of mermaids like Medieval men reading psalters could look at images of mermen and relate to them or feel encouraged or impassioned by the heroism that these mermen depict. In other words, the presence of these images in these Medieval manuscripts greatly influences the people who consume these images as entertainment or viewing pleasure and further contribute to the social idea that women exist solely for sexual pleasure while men exist for glory and accomplishment.

The Medieval Siren’s Song

Although mermaids experience an objectifying transformation throughout Medieval manuscripts, the presence of sirens returns feminine power to the merfolk species. Sirens represent the malevolent mermaids who attack sailors and sailors to their imminent death, and the key element of sirens’ magic originates from the siren’s magical voices, which sirens use to lure sailors to their deaths. As previously mentioned, the majority of sirens appear in the form of half-bird, half-woman creatures. On the subject of the half-bird nature of sirens, Elizabeth Eva Leach, a musicologist who specializes in music of the Middle Ages, asserts: “Medieval sirens normally appear in bestiaries among the bird entries, and are for the most part the same hybrid—woman to the navel, with the lower half a bird. Imagining the siren as half-woman halfbird makes her singing ability even more prominent and expected; it also promotes the siren’s pairing with the nightingale as her female songster counterpart.” In this quote, Leach compares sirens to nightingales, birds known for their powerful singing voices and beautiful tunes, due to sirens’ original appearance as half-bird, half-human creatures. The connection between singing birds and sirens remains a common theme throughout Medieval literature. In the novel The Romance of the Rose, one of the most classic stories of Medieval courtly love, the narrator enters a beautiful garden and falls in love with a rose, thus sending him on a mighty journey to earn the trust and consent of the rose so that he may finally make love to the rose. The allure of enchanting birdsong catalyzes the narrator’s entrance into the garden, which he compares to the sound of singing sirens: These birds that I am describing to you did most excellent service. They sang as though they were heavenly angels, and you may be sure that when I heard the sound I rejoiced greatly, for never was so sweet a melody heard by mortal man. So sweet and lovely was that song that it seemed not to be birdsong, but rather comparable with the song of the sea-sirens, who are called sirens because of their pure, sweet voices. The narrator concludes his thought with the assertion that sirens earn their name due to their “pure, sweet voices.” The notion that the voice of the siren is “pure” feels particularly off-putting since sirens possess a reputation for luring sailors to their death. Unless one is actively enchanted by sirens, one would think that the sirens’ voices would seem neither “pure” nor “sweet” because they originate from evil creatures with evil intentions. Additionally, the narrator compares sirens to birds that seem like “heavenly angels” because “never was so sweet a melody heard by mortal man,” yet the actions of sirens separate them quite drastically from “heavenly angels.” The mention of “mortal man” accentuates the occult powers of sirens because they exist as supernatural creatures above the natural plane of human existence. Ultimately, this bizarre notion of sirens as benevolent creatures emphasizes their seductive capabilities; despite the horrifying myths surrounding sirens, Medieval individuals still find themselves fascinated with the allure of these creatures and opt to consider sirens with admiration as opposed to fear. In a sense, this notion actually emphasizes how successfully sirens manipulate their prey.

Conclusion

Medieval mermaids serve as supernatural female archetypes. However, as mermen appear within Medieval manuscripts, mermaids become more sexualized in the presence of mermen. While mermen wear cloth garments or armor to conceal their chests, mermaids lack clothing and instead expose breasts that become increasingly idealized throughout Medieval manuscripts. Moreover, the presence of mermen subdues mermaids into static, decorative roles. Initially, mermaids conduct a variety of activities in Medieval manuscripts, such as standing idle without suggestive postures, playing musical instruments, and using weaponry in rare circumstances. However, as mermen begin appearing in manuscripts during the 1400s, mermaids almost solely comb their hair and look into mirrors. These mirrors represent the mermaids’ vanity as they admire their own beauty, therefore connecting mermaids to Eve and further emphasizing mermaids as a sinful female archetype. By the same token, the spherical shape of the mirrors represents the moon disks commonly depicted with lunar gods, therefore accentuating the occult powers typically associated with sirens. Sirens utilize magic to sing melodies and lure sailors to their deaths and therefore obtain their powers directly from their ability to seduce men. Thus, even when sirens appear as powerful creatures capable of tricking and killing sailors, they appear powerful solely because of their sexuality. On the other hand, mermen appear powerful due to their armor and skills with weaponry, and images of mermen raising phallic sticks over their heads emphasize their masculine sexuality. Ultimately, mermaids forfeit their agency to act as sexual entities for the merfolk species, therefore allowing mermen to act as heroic entities for the merfolk species.

Idealizing the bodies of Medieval Mermaids: Analyzing the Shifted Sexuality of Medieval Mermaids in the Presence of Medieval Mermen. By Chloe Victoria Ruby Crull. Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, February 26, 2021.

Mermaids, in all their incarnations, from Disney’s resourceful Ariel to the darker creatures of folk myth, are big news – moving on from the school accessories where their likenesses have long decorated bags, pencil cases and water bottles. Suddenly there are growing numbers of mermaid academies and swimming schools, an annual Merfolk UK convention (this year’s will take place in the unlikely environs of Snaresbrook, north-east London) and any number of professional mermaids for hire.

But it is in literature and film that the new generation of mermaids are making waves. A number of new novels take the mermaid myth as their central theme, from Imogen Hermes Gowar’s much-hyped historical fiction debut The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock, out at the end of this month, to Kirsty Logan’s second novel The Gloaming, which features a mermaid impersonator who may be more than she seems. Melissa Broder’s The Pisces, in which a young woman falls in love with a merman, is also out this spring.

In cinema, a remake of The Little Mermaid is planned, which will see Lin-Manuel Miranda, creator of the hit musical Hamilton, working with the original film’s composer, Alan Menken. Another movie of the same name tells the story of a young brother and sister who encounter a mermaid trapped in a tank. Then there’s a gender-switched remake of the 1980s classic Splash, with Channing Tatum in the role that made Daryl Hannah a star.

Even this year’s Oscar frontrunner, Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water, alludes to the myth, with the tale of a lonely janitor (Sally Hawkins) who falls in love with the Asset, a captive creature who is both human and amphibious, a merman in all but name.

“I think part of the reason we are so drawn to mermaids is that they are females with agency, particularly sexual agency,” says Hermes Gowar, whose debut novel follows the varied fortunes of a merchant whose captain sells his ship for a mermaid, and the courtesan into whose orbit he subsequently floats. “They’re beautiful of course but they are also strong and active – they can swim in deep seas and have a real, dangerous power over men.”

Liz Foley, publishing director at Harvill Secker, who will publish both Hermes Gowar’s novel and Logan’s The Gloaming, agrees. “Part of the appeal is definitely an element of escapism in grim times but it also goes deeper than that,” she says. “When you really examine the mermaid myth there’s a lot there about grief, loss, sexuality and freedom.

“I think what we are seeing is a growing number of female writers reappropriating the mermaid story and raising interesting questions in the process.”

In that sense the new wave of mermaid tales are the opposite of all those stories of passive princesses marketed for so long to little (and not so little) girls as the ultimate feminine ideal. “The story of the mermaid is the story of a very male sort of fear, the fear that a woman is always going to leave you or destroy you,” says Logan, who describes The Gloaming as “a queer mermaid love story”.

“The appeal of mermaids is that they aren’t just pretty and docile. They’re beautiful, exotic, unusual and powerful and even when prettied up on a pencil case they are still the same strong creatures who can sing men to their doom.”

Logan believes that the mermaid myth also has a particular appeal in today’s gender-fluid world. “My whole life I have felt as though I lived between two states,” she says. “I’m a bisexual Scottish woman who was born in England and even though I moved back still have an English accent. I’m not quite one thing and not quite the other, and I do think that’s why I have always been so interested in stories of selkies [seals in water, humans on land] and mermaids because the key to those stories is that they change between states.”

Irish writer Louise O’Neill’s much-anticipated The Surface Breaks, published by Scholastic this May, has been described as “a dazzling feminist retelling” of the most famous mermaid tale of them all – Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid.

“It’s ripe for a feminist interpretation,” she told the Observer, “because there is so much in it about gendered behaviour, especially for young girls and about how they should behave in the world.

“That notion that girls should be likeable and agreeable – that they should effectively silence their voice as the little mermaid does – is worth challenging.

“Plus, I really wanted to look at the sea witch, the banished woman, because in many ways she is the most fascinating character in the story.”

According to O’Neill, at least part of the explanation for the mermaid revival lies in nostalgia. “For women of my age,” she says, “in our late 20s and early 30s, The Little Mermaid was the Disney film.”

Ultimately though, says Hermes Gowar, it’s about a 21st-century take on power and sexuality. “Historically I think we have always cast mermaids’ freedom and sexual power as something dangerous [luring men away from home, dashing ships on rocks] and harmful to communities,” she says.

“Mermaids were an object lesson to young girls, teaching them that pursuing their appetites and desires is selfish and destructive. Nowadays there is such a movement to reclaim women’s sexual agency that it makes sense we are also reclaiming mermaids at the same time.”

Magical and gender-fluid … the enduring appeal of mermaids. By Sarah Hughes. The Guardian, January 7, 2018.

Over the past year, I have developed a strange new obsession… with mermaids. This has taken me from talking at the British Museum for LGBT history month, to running a drag-filled screening of The Little Mermaid at the National Maritime Museum! I am not a curator or an art historian – if anything I would like to call myself a ‘mermaid hunter’. Today I would like to tell you a little about what this means and why mermaids are such a powerful symbol for the queer community.

Which brings us to Belle, the newly dubbed "feminist" star of Beauty and the Beast(opens in new tab). Belle is often given credit for kick-starting the progressive streak in modern Disney heroines, and it makes sense: She's feisty, well read, outspoken, and not here for chauvinism.

But there's another Disney icon whose significance to a marginalized group isn't getting its due: The Little Mermaid's Ariel, who has an under-appreciated trans message. Here, the reasons she's a more important icon now than ever—and why we should start looking at her differently.

Think about it. Ariel feels trapped in a body that's foreign to her. She'd like to replace a prominent appendage (her fins) with something that feels more "right" (legs). She is all but disowned by her biased father, and misunderstood by her beautiful, traditionally feminine sisters. She collects artifacts that represent the life she'd rather be living. She surrounds herself with friends who are also considered outcasts. She's repressed by the expectations placed on her, and oppressed when she lashes out against them.

In 2015, PBS aired the documentary Growing Up Trans, which follows the lives of several trans children, including a 13-year-old named Ariel. She selected the name because of her love of the mermaid, whose story felt in line with her own. Real-life Ariel isn't alone. Numerous trans women have talked openly about seeing Ariel as a metaphor for their own journey—including London-based comic and writer Shon Faye.

"Ariel was always my favorite Disney princess," Faye told BuzzFeed(opens in new tab). "I always strongly identified with her, probably because we're both trans women. I mean, I'm just transgender, whereas I guess Ariel is trans-species, but you know, getting here wasn't an easy ride for either of us."

Ariel's struggles reach their peak in the iconic song "Part of Your World," an anthem for anyone whose personal identification might not align with their physical presentation. She starts the song by acknowledging her privilege as a princess ("Wouldn't you think I'm the girl who has everything?"), but admits that she wants more, wondering aloud "What would I give if I could live out of these waters?"

"When I was little, hearing themes I was struggling with in 'Part of Your World' did me a lot of good," Jos Truitt wrote on Feministing in 2010. "If the Disney princess was singing about what I was feeling maybe I wasn't so alone, so weird and wrong, after all."

Though there's obviously a huge and important distinction between being transgender and being gay, the fact that the man responsible for Ariel was bisexual speaks intrinsically to the story of oppression in the character's narrative.

The Little Mermaid was based on the beloved fairy tale of the same name by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen in 1837. Andersen was famously celibate , but also harbored unattainable infatuations with both men and women. The unreciprocated love he had for his benefactor Edvard Collin may be what inspired him to write The Little Mermaid (which originally had a much darker take on unrequited love and sacrifice), and lends new understanding to the film's origins as a tale of otherness.

Why Ariel from 'The Little Mermaid' Is an Overlooked Trans Icon. By Lindsay Romain. Marie-Claire, March 22, 2017.

I don’t chase beauty trends. In fact, I have maintained the same makeup routine for nearly a decade. This may seem like blasphemy coming from a columnist for the beauty bible, but I just know what works for me. Bronzer, gold eye shadow, and cheekbone highlight; a coat of beige-pink gloss from Jay Manuel; and a few coats of mascara. Done!

No comments:

Post a Comment