In painting I was able to satisfy my leg and nipple fetishism.

—P. Molinier

Pierre MOLINIER

born on 13 April 1900 died around 1950

he was a man without morals

he was proud of it and gloried in it

No need to pray for him.

Chachki—drag queen, model, recording artist, and winner of season seven of RuPaul’s Drag Race—wrote on Instagram shortly after the video’s release that it is a celebration of the French Surrealist artist Pierre Molinier’s work and ideas. This opening scene—which mirrors Molinier’s photograph Le Chaman—is just one moment where this connection becomes clear.

Molinier originally trained as a painter, but is best known for his erotic imagery. He photographed himself—often dressed in corsets and fishnets, holding fetish accessories, or wearing masks—then copied and cut out the images of his body and reassembled them into a single montaged image. “Whatever Violet Wants” brings Molinier’s work to life, recreating and animating the tangle of limbs and fetishistic imagery in an entirely new context.

I recently spoke to Chachki about the making of the music video, the art of drag, and how Molinier and other modern artists influence her work.

Isabel Custodio: Take me through the genesis of this project. How did you choose “Whatever Violet Wants”?

Violet Chachki: I’ve always loved the Sarah Vaughan cover of “Whatever Lola Wants.” I think I first heard it in the movie Kinky Boots, which is about a drag queen who opens a shoe factory in the UK. It’s a very drag, sort of fetishy song about getting what you want and being confident. My drag character is very dominant and domineering, and that’s a quality that I am inspired by. When I see strong, confident women who really know what they want and get what they want, that’s the kind of woman that inspires my drag, so putting a new spin on “Whatever Lola Wants” and doing “Whatever Violet Wants” felt very appropriate.

IC : You’ve said that this video is a celebration of the artist Pierre Molinier’s ideas. How do you see the themes of his work in relation to your drag?

VC : I’ve always been into subcultures. In the ’50s and ’60s, what Pierre Molinier was doing was super subculture—he was taking self-portraits, it was very private, very intimate. I think that’s actually how I started my drag—in my bedroom, taking MacBook self-portraits. There’s something really intimate about getting in drag in your bedroom in the safety of your own home. Especially for me, as a 16-year-old or a 17-year-old taking self-portraiture. That’s one of the ways that I see me and Molinier’s work overlap.

I also identify with his surreal aspects. I think his work has a real escapism to it, which is another thing that I love about drag. You literally get to escape and become someone else and go into a different world. The surreal aspect that Molinier brings into his pieces transports you. The fact that he was doing them before Photoshop—cutting up negatives and creating these surreal images by hand—is just so cool to me. I discovered him right around the time that I was getting into drag and getting into celebrating my feminine side and getting into escapism as a form of therapy.

I see myself in him a lot. I think there’s something really exciting about fetish gear and high heels. He would use a lot of props and fetish imagery—there’s something counterculture and taboo about it. I always have been excited by taboo things, especially growing up, going to Catholic school. And I think that was something that he thought was exciting as well, being a bit naughty, I guess. You’re not supposed to do these things, so you do them in private.

IC : You were able to use some of Molinier’s actual props in the video. How did that opportunity come about? Were you working with his estate?

VC : There was actually an auction a few years ago of his estate, and there were so many props, and shoes, and masks, and everything. I was devastated because I wasn’t in Paris to go to the auction and buy something, because that would be my dream, to own one of the props. Everyone in Paris was going crazy for it at the time, and I think the props just got bought out by everybody and dispersed around Paris. I know Christian Louboutin bought some stuff.

I don’t know exactly who we bought the props from, but it was one of the video’s director’s friends who was at the auction and bought a bunch of the props. We were so, so lucky to have some of the actual pieces. It was so cool to be able to wear them. And, of course, we handled them with great care and respect. But I’m hoping one day I’ll be able to purchase a prop of his myself.

IC : Throughout the video, you go back and forth between being in and out of drag. It almost gives you another character: a desirer and a desired. Can you walk me through the decision to portray yourself that way?

VC : I think it’s nice to showcase yourself as you are. Drag queens are celebrated so much on stage and when we’re presenting as our most creative selves. But it is jarring being onstage in front of 5,000 people, and then—it’s really cliché—but you go back to your hotel and you’re all alone. It’s difficult to be celebrated in drag and then be way less celebrated out of drag. I think I’m also making a conscious decision as I get older to take time for myself and to celebrate myself without makeup—to showcase my natural beauty, I guess, even for my own enjoyment, and to document myself outside of drag and where I’m at in my boy self. Even just posting a boy selfie on Instagram, I lose, usually, thousands of followers. So it is an interesting conversation to think about.

I can just hear the video’s director, Ali Mahdavi, in his thick French accent: “You are such a beautiful boy as well.” [In the video] he made the decision to start off out of drag, and then get a little distorted in the middle, and then toward the end in more full high drag. I think that adds a surreal element that’s in touch with Molinier’s. There’s even one part where there are two of me out of drag, licking myself in drag.

IC : Unlike your video for “A Lot More Me,” where these intricate, colorful sets play such an important role, your video for “Whatever Violet Wants,” like a lot of Molinier’s work, really came together in post-production. Can you talk about that process and how you wanted the video to visually echo Molinier’s work?

VC : I never thought of taking one of Molinier’s images and making it move. And that was Ali’s idea, to take his work and make it even more interesting as a video, because we’ve only seen his work as a still before. So, it was definitely a struggle, and it took a very, very long time, and lots of convincing and throwing money at it. It was definitely difficult to get the post-production correct. Like I said, it’s not the most CGI-gorgeous stuff either, but again, I think that lends itself to Molinier’s work. Even just all the green screen work and getting my lips to be separated and then getting me to kiss myself, it is a lot of finessing. I mean, I’m not Beyoncé. I don’t have, like, endless amounts of post-production money either. But it’s nice because Molinier’s work is a little DIY and a little cut-and-paste. In his work you can really see the scissor snips and all those things. I like that the video echoes that.

IC : You’ve said that drag is all about taking references from pop culture and flipping them on their heads. You’ve specifically cited Erté, Tom of Finland, Busby Berkeley, John Willie, and Dita Von Teese as inspirations. These aren’t pop culture figures that you’re going to find in a lot of mainstream discussions. I’m curious where you first encountered these figures and where you continue to find inspiration for your work.

VC : I am a child of the Internet. Tumblr is really what changed the game for me. I got exposed to things in print as well. I remember seeing Heatherette in my friend’s Teen Vogue, and little things like that. But what took it off for me was the Internet. I would see something on Tumblr that I liked, and it would have a little caption. Then I would Google the caption, and then I would find more stuff. And it just kept building and building.

And then even with Tumblr, you can like something. So you have an archive of all these things that you’ve discovered. I still, to this day, will go back to my old Tumblr, even though there’s lots of vintage porn that has been removed, and the smutty stuff I liked—John Willie or Tom of Finland—is no longer allowed on Tumblr.

And I hate that I’m saying “the Internet,” because I’m really old school. And I do not relate to the youth of today, as far as TikTok and what today’s version of Tumblr, Instagram, or MySpace would be. I was at the right place at the right time as far as the Internet is concerned.

IC : You’re using references that feel very sexually progressive and very unafraid of displaying queer identity. It feels relevant to a lot of the most eye-roll-inducing parts of Pride discourse, specifically about kink. What I love is that you seem to put your stake in the ground and you’re saying, “This is me. I’m in charge of this, and I’m not even going to entertain this conversation.”

VC : Yeah. The same conversation happens around drag. There are certain events where people think that it should be a family-friendly drag event. Of course, that’s not what this is about for me. I think the way the world works is that there are cultural differences and subcultures. Some things are not for everyone, and some things are inappropriate for other people to partake in. And I think that that is more than okay. I think that’s a positive thing. For me, drag is my therapy. Drag is something that I do to escape, to relieve, to celebrate. It’s not necessarily for your children. It’s for me. And there’s nothing wrong with that. You can’t sanitize queer people. It’s not a thing. I mean, not if I’m around.

I think about the Sex and the City episode where one of them loses her shoes. She’s like, “What about me? What do I get for not having children? What do I get for not getting married?” There are so many rewards for people who are married and have children. And there should be nothing wrong with being single, having no children, and wanting to design your life that way. The fact that everyone who does have children wants you to think about their children when you’re making your everyday decisions—it’s like, give me a break. Even as drag queens, we get flak from conservatives because parents will bring their children to drag shows and drag events. Then all of a sudden these conservative people are yelling at us. I’m like, “This isn’t my kid. I didn’t bring them.” This has nothing to do with me. I just hate how it has become everyone’s responsibility to parent other people’s children. That’s not my responsibility, darling.

IC : Right, and I think that ties back into Molinier’s work and life. I know that he initially was involved with other Surrealist artists. André Breton invited him into his circle, but his work was deemed too radical, too queer. Eventually they parted ways, and Molinier basically worked on his own. What’s interesting is you’re doing the opposite in a way. You’re taking an art form that has been underfunded and undervalued, and entering these very traditional, elite institutions like the Met Gala and Fashion Week. I’m wondering if you see this as a final chapter of Molinier’s legacy—reappropriating these images, but in a totally different social context.

VC : It’s interesting you bring that up because I feel like I’m dealing with a similar scenario. For instance, booking a beauty campaign. A lot of drag queens have gotten beauty deals, but it seems like the nature of my work—whether it be Molinier posing in lingerie or corsets, or something else—is a bit more provocative than, say, your average storyteller drag queen. Brands and companies are more willing to give work to more palatable, commercial drag performers who can appeal to the widest audience possible. But you are right in saying that I have brought my style of drag and pro-sex style to these spaces. I think the art world can respect it way more, and I consider the fashion world to be a part of that. But there’s not a lot of money in fashion or art. These days, making money is really about selling products. But I think the art and fashion worlds can see the artistic value in what I do and in what Molinier did—in hindsight now, of course.

IC : Drag feels like the most personal and all-consuming art form. You’re responsible for the complete invention and presentation of a persona. I’m wondering if this makes evolution harder as an artist. Does it ever feel like it’s difficult to experiment because there’s an expectation of who Violet Chachki is, and what a Violet Chachki show might look like?

VC : I don’t like to experiment too much, for a couple of reasons. One is that there are just so many drag queens. And there are a lot of drag queens who I don’t think would’ve doing drag even five or six years ago. The acceptance level and the work in the industry has come so far in such a short amount of time that it has become completely oversaturated. So you really have to pick something and stick with it, because you’re bound to get mistaken for someone else. That’s the worst feeling—it has happened to me so many times, where I’m out at an event and I get mistaken for another drag queen.

So you have to have a style and stick with it, and be the best at it. That’s what I try to do: know who I am, and deliver at all times. At the end of the day, show business is a business, and it costs. Drag is really expensive, and you have to stand out if you want to get work and be the best in whatever style you’re doing. Drag, for me, is not a forever thing. Glamour and escapism are the principles that I will always be in search of, whether it’s drag or a different sort of creative outlet. I’m trying to get all of the things I want to do done while I still have interest in the art form.

IC : You have said that your Digital Follies show, for example, is allowing you to document a very specific point in your career. I’m wondering how this relates to your use of references and your sources of inspiration, because so many of them come from an era when documentation, at least relative to now, was scarce. Are you thinking about the documentation you’ve missed from these sources or what you’re leaving for the future?

VC : Yeah. I think that I also like to come back to things and do them better. For example, I did an Erté number in 2012, but it was horrible because I didn’t know what I was doing, and I didn’t have the experience of drag to execute the vision. And so I constantly revisit ideas and try to do them better.

For me, documentation is super important. I am planning on doing a book at some point. I also want to have a lot of footage, so we’re constantly taking behind-the-scenes videos. Of course, there’s also the wardrobe. I feel like I’m running a small museum with these clothes—keeping track and taking care of everything is such a chore, and making sure all of that stuff is preserved and documented. It is important to me to archive everything and to sort of check all the boxes of the things that I want to do and document them properly. One day, maybe there’ll be a retrospective. I have no idea.

Violet Chachki on the Art of Drag. The drag superstar talks about queerness, families, and

her tribute to the transgressive artist Pierre Molinier. By Isabel Custodio. MoMA Magazine, June 16, 2021.

After capturing himself on film, Molinier would typically use silver scissors to cut around the body contours in the photos he had just shot, and reassemble them into a single photomontage of his own body; a mise en abyme -- or, the same image replicated to give the impression of infinity -- that he would immortalize with his folding camera.

Born in 1900, Pierre Molinier's life and work as a painter and photographer was filled with dark fantasies and sensational anecdotes. He is infamous for his fetishistic depictions of women's legs, his disturbing obsession with his sister, his taste for firearms, his wanderings in silk stocking along the streets of Bordeaux, and his tragic end in 1976 on his bed, a pistol in his mouth.

His enigmatic photographs continue to fascinate audiences, artists and photographers, and his multifaceted body of work, with its fantasized and fetishized bodies, is still challenging to this day.

Famous shoe designer Christian Louboutin explores the world's treasures

Originally trained as a painter, Pierre Molinier began his artistic career in the late 1920s, producing landscapes and portraits inspired by Impressionism. But then he took a change of course, and in 1951 he presented a controversial erotic painting at a respectable art salon in Bordeaux. Entitled "Le Grand Combat," it depicted a swirling multitude of (possibly women's) legs in fishnet stockings, and, shortly after, he started to send images of his works to poet and writer André Breton, the godfather of French surrealism.

His and Breton's encounters led to a solo exhibition at the famous Paris surrealist gallery L'Etoile Scellée in 1956, exposing Molinier's work to a wider audience. On the opening night, Breton wrote to Molinier: "Today, you've become the master of vertigo. Your photographs don't leave a shadow of a doubt as to your aspirations and it seems difficult to me to be more troubling. They are as beautiful as they are scandalous."

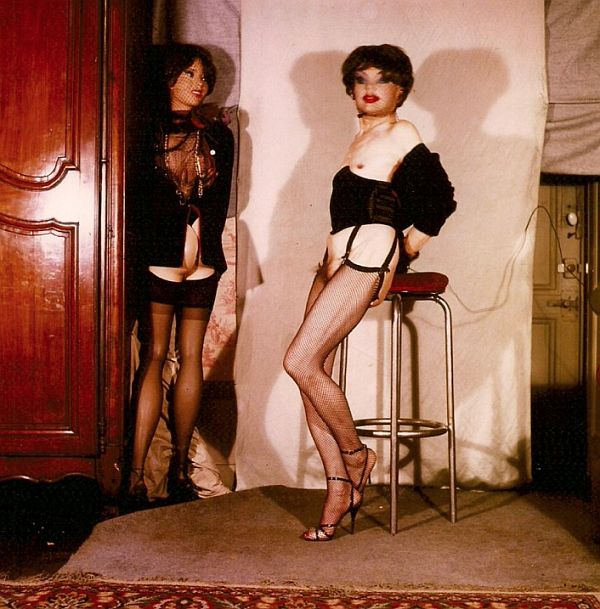

Moving away from painting, in the early 1960s Pierre Molinier started to dedicate his practice to photographic work, mainly self-portraits, enhanced by a process of photomontage. His technique often consisted of photographing himself dressed-up, body hair waxed and with make-up on, his face covered with a mask and him dressed in black fetish accessorizes -- corsets, gloves, stockings and high-heels, veils, fishnets, and sometimes a top hat. He would then cut around the outlines of the body parts in the photos and reassemble them in a final collage photograph; an ideal image of himself. Sometimes, he would replace his own head with the face of a doll. The process was similar to the enduring surrealist group drawing game, "Exquisite Corpse." And although he was greatly influenced by the surrealists, Molinier never officially joined that movement, remaining a lone practitioner throughout his life.

Costume was core to his experimental works. Whether dressing up for a self-portrait or using one of his male and female models -- some of whom were his lovers -- all subjects were disguised with outfits and wigs, posing against backdrops of dark fabric in swathes. This theatricality was also a key part of his practice, as he typically shot his erotic scenes in the bourgeois interior of his studio in Bordeaux, using baroque screens, velvet curtains and floral wallpapers as backgrounds. This provocative contrast between the erotic and the acceptable caused an electric tension in his images.

Throughout his artistic practice, Molinier deconstructed sexual identities, dismembering the representations and stereotypes of the masculine and the feminine self, stirring up gender trouble and transgressing the presupposed sacredness of the indivisible body.

His depictions of transgender, androgynous and transvestite bodies, which were cut up, reassembled and played with, invented a surrealist, pornographic theater of uninhibited desires and fantasies, utterly shocking the French bourgeois audience of the 1960s. His work was considered by many to be perverse, even depraved, and despite Breton's efforts, Molinier was never accepted by the French cultural elite.

But it is perhaps because of the unflinching nature of much of his work that Molinier's major legacy has endured, spanning across contemporary visual art, photography, fashion and cinema. His first posthumous retrospective was at Paris' major institution Centre Pompidou, three years after his death, and he is frequently included in shows that explore themes of identity, queerness and photographic innovation, Kiss My Genders at the Hayward Gallery in London was a recent one.

His influence can be seen in the work of hugely influential Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, and controversial American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe -- in its eroticism, fetishism and sexual powerplay. And in the work of Cindy Sherman, whose own self-portraits pushed the boundaries of gender and identity in photography.

French filmmaker Gaspard Noé has expressed his deep fascination for Molinier's colorful character as much as for his decadent images, while fashion designers such as Jean-Paul Gaultier and shoe designer f have carried Molinier's heritage in their collections; his aesthetic mythology and his ode to provocation, mystery and desire.

Not just complex in its technique and subject matter, Molinier's kaleidoscopic images confronted traditional ideas of power, domination and gender fluidity. They can be seen as icons for a post-gender era, and the photographer himself as a trailblazer for today's queer and questioning culture. His photomontages of merged body parts transgressed the limits of the human form, creating a space to imagine new visual possibilities -- and political possibilities too.

The lone surrealist whose erotic art provokes to this day. By Martha Kirszenbaum. CNN, April 29, 2020.

Who? An

account of French artist Pierre Molinier’s colourful life reads like that of

the protagonist in an Oscar Wilde novel. A product of France’s

oft-fictionalised fin de siècle degeneration, Molinier defied all societal

norms to live a life of hedonistic excess. Both homosexual and a transvestite

in an era when both were frowned upon – he asbcribed himself the title of

‘lesbienne’ – Molinier pursued fetishism and the latent eroticism of the

subconscious mind to its most extreme degree.

Born in France in 1900, Molinier began his career as a lowly and unexceptional house painter. In fact it wasn’t until he moved to Bordeaux, the city which marked the beginning of his self-discovery, that he began to delve into the underground culture of 1920s France. He quickly joined a secret society and began to express his fervent interest in the arts, strongly advocating the fashion of the day for throwing ‘salons’ – intimate get-togethers with a select number of likeminded individuals – and showing his erotic, experimental and magic-infused artwork with his peers.

By 1955 Molinier had begun a fruitful correspondence with André Breton, the founder of Surrealism, who dubbed him 'the magician of erotic art' and decided to include his sensual, and at times violent, works in the International Surrealist Exhibition. This marked the artist’s official induction into the movement, and he soon earned a reputation as an artist who would dare to execute the ideas his reputable contemporaries, who included the likes of Salvador Dalí, only dreamt of.

His investigation into fetishism and depravity, both through painting and photography, steadily gathered momentum, culminating in an extensive series of portraits and self-portraits in which Molinier himself often features as a many-limbed woman, a dominatrix, or a devil. When his dwindling health prompted his death at the age of 76, it was executed with the all the charisma his character would suggest; a great lover of guns, he died from a single self-inflicted gunshot wound. The death befitted the gravestone the artist had built for himself 26 years earlier, which read: "Here lies Pierre Molinier, born on 13 April 1900, died around 1950. He was a man without morals; he didn’t give a fuck of glory and honour; useless to pray for him."

What? To call Molinier a master of disguise scarcely seems to do him justice. Costume formed the central tenet of his experimental works, whether it was worn by the artist himself – he loved to dress up as woman in fetishwear, doll's masks and women's accessories for his many self-portraits – or by his subjects – men, women and lovers he disguised with the outfits and wigs, and who posed against a backdrop of swathes of dark fabric.

Throughout his career, the artist insisted that he created work purely for self his own pleasure; he described eroticism as “a privileged place, a theatre in which incitement and prohibition play their roles, and where the most profound moments of life make sport.” His production methods were often as unusual as the images which came of them. A great believer in the results to be had by intervening in the image-making process, the artist often pleasured himself while pressing the shutter, and mixed the product of his climax with colour pigments in the course of developing the image.

His photomontages present an especially compelling and fantastical vision. By cutting and pasting body parts and textures from various different photographs to create a final image, Molinier found that he was able to conjure the many-limbed creatures from his own psyche, and hoped that, on seeing them, viewers of his work would be similarly surprised by their own repressed, fetishistic instincts. 70 of these montages were included in The Chaman and its Creatures, an unfinished artist's book made in 1967, to which the foreword reads: “at all times, my acts and my actions in life have stemmed from love or eroticism.”

Why? Though Molinier’s photographs are neither as shocking nor as revolutionary now as they would have been to a conservative audience in 1950s France, the artist was utterly groundbreaking in his willing embrace of the darkest elements of his own desire. He continually challenged received orthodoxies on art, morality and religion, forcing the advancement of thinking on freedom, integrity and equality in the process. It’s little surprise, then, that his influence continues to resonate in contemporary art today – artists including Cindy Sherman, Robert Mapplethorpe and Ron Athey count him among their forerunners, and the themes of Surrealism and photo-collage he perpetuated continue to play an important role in the art industry.

This Friday a sale of his work, assembled by his former lover and muse Emmanuelle Arsan and hosted by Artcurial, will take place in Paris, including 200 photographs, collages, drawings and personal letters by the artist. That its name, The Forbidden Sale, would have pleased Molinier only makes the possibility of owning part of the collection more enticing.

The photographs reveal things as though through a keyhole, spotlit vignettes rearing up from a forbidden world. They are small, black-and-white, home-developed silver gelatin prints, and they glower round the walls, not so much inviting as inciting you to look.

Employing the uncanny, the art of French post-war, post-Surrealist Pierre Molinier and BREYER P-ORRIDGE, the ongoing collaboration between Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV’s Genesis Breyer P-Orridge and h/er now-late wife Lady Jaye, both uncover the transformative and transcendent power inherent in the malleability of the human body.

Pairing these artists in an arresting, unsettling and ultimately inspiring show, Invisible-Exports’ BREYER P-ORRIDGE & Pierre Molinier exhibition forges a powerful aesthetic genealogy between these uniquely subversive artists. Filled with fetish imagery from fishnet tights to dildos and sky-high heels, including BREYER P-ORRIDGE’s aptly named “Shoe Horn,” the exhibition combines BREYER P-ORRIDGE’s pandrogene works with Molinier’s autoerotic black and white photomontages, allowing viewers to perceive the links between these artists, as well as witness the identity destabilizing possibility in body modification.

For artists like BREYER P-ORRIDGE who, at least to me, have always seemed almost peerless in their explosion of the binaries of sex and gender, the discovery of Pierre Molinier, who also dared transform his own physical being through technological means, provides an essential link in the trajectory of transgressive art.

Quite frankly, I only recently found Pierre Molinier’s demented photomontages in the pages of the enormous tome Art & Queer Culture, which rendered me staring stunned at Molinier’s multiple nylon-ed legs and mannequin mask, which appeared almost like a proto-Narcissister.

A contemporary of the Surrealists and, as his epitaph states, “a man without morality,” Molinier, through the aid of a mirror and photographic manipulation, investigated his own erotic fixations, which even alienated the Surrealists due to his highly disturbing sexual imagination. As Catherine Lord details in Art & Queer Culture, “Andre Breton who became interested in Molinier in the mid-1950s, ceased to publish him ten years later when Molinier proposed a painting of Christ with a dildo up his arse”

In the photographs throughout Invisible-Exports, Molinier’s fetishistic montages uncannily erase the separation between animate and inanimate objects through his wild array of limbs, asses and dead-eyed female mannequin masks. In “The Uncanny,” Freud quotes fellow uncanny theorist Ernst Jentsch who placed the source of the uncanny with “doubts whether an apparently animate being is really alive; or conversely, whether a lifeless object might not be in fact animate” (5). Highlighting uncanny objects such as dolls, wax figures and automatons, Jentsch’s animate confusion reflects Molinier’s own blurring of these divisions.

Like Jentsch’s dolls, Molinier’s self-portraits appear almost inhuman–a surreally fantastical and almost nightmarish conglomeration of body parts, piling limbs upon limbs and fracturing the apparent stability of anatomy. Not only disturbing the seemingly strict difference between animate and inanimate objects, Molinier’s photomontages also break the binary boundaries between the genders, as well as the unchangeable understanding of the biological human form.

Discovering Molinier h/erself in a book on Surrealism while attending a conservative English public school, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge writes on Molinier’s work: “Art like Molinier’s and similar works attempt to solve this auto-destructive trajectory by proposing both a vision of time as a congregation of loops and looping that in themselves require a sense of responsibility for a future as we might all experience just that! And by proposing a massive rethink of our attitude to the human body. A final declaration that it is NOT sacred in any way, merely a cheap suitcase to give mobility to consciousness…”

Mirroring Molinier’s rejection of the sacredness of the body, BREYER P-ORRIDGE’s literal transformation of the body similarly erases these constrictive and restrictive binaries.

Taking William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s conception of the cut-up to its absolute limit, BREYER P-ORRIDGE create a collective “third mind” or the “pandrogene” by cutting up the body through cosmetic surgery. Through numerous procedures to look the most like each other as possible, Genesis and Lady Jaye, as BREYER P-ORRIDGE, transcend the singular idea of the self.

As BREYER P-ORRIDGE explain in “Breaking Sex,” “We are required, over and over again by our process of literally cutting-up our bodies, to create a third, conceptually more precise body, to let go of a lifetime’s attachment to the physical logo that we visualize automatically as “I” in our internal dialogue with the SELF”.

Through post-surgery Polaroids, as well as Molinier-esque images of reflected body parts and fishnet fetishism, BREYER P-ORRIDGE also engage with the uncanny through the eeriness of “doubling.” Pointing to the double as a source of the uncanny, Freud states, “These themes are all concerned with the idea of a ‘double’ in every shape and degree, with persons therefore, who are to be considered identical by reason of looking alike; Hoffmann accentuates this relation by transferring mental processes from the one person to the other–what we should call telepathy–so that the one possesses knowledge, feeling and experience in common with the other, identifies himself with another person, so that his self becomes confounded, or the foreign self is substituted for his own–in other words, by doubling, dividing and interchanging the self.”

Through this “doubling, dividing and interchanging the self,” BREYER P-ORRIDGE assert that the binary systems integral to institutional and societal control can be overcome. In “Breaking Sex,” BREYER P-ORRIDGE reveal, “BREYER P-ORRIDGE believe that the binary systems embedded in society, culture and biology are the root cause of conflict, and aggression which in turn justify and maintain oppressive control systems and divisive hierarchies. Dualistic societies have become so fundamentally inert, uncontrollably consuming and self-perpetuating that they threaten the continued existence of our species and the pragmatic beauty of infinite diversity of expression. In this context, the journey represented by their PANDROGENY and experimental creation of a third form of gender–neutral living being is concerned with nothing less than strategies dedicated to the survival of the species”.

By rejecting these binary systems, both Molinier and BREYER P-ORRIDGE expose the weaknesses in the restrictions of the human body. Returning to Freud’s understanding of the uncanny as a familiar idea that has been repressed, perhaps Molinier and BREYER P-ORRIDGE’s work causes such a destabilizing sense in viewers due to the underlying truths exposed within them–that the body is not sacred, that it is a potential artistic material like any other and that through this body manipulation, alternative forms of post-binary existence can be found.

As BREYER P-ORRIDGE state in “Breaking Sex,” “When you consider transexuality, cross-dressing, cosmetic surgery, piercing and tattooing, they are all calculated impulses–a symptomatic groping toward a next phase. One of the great things about human beings is that they impulsively and intuitively express what is inevitably next in the evolution of culture and our species. It is the Other that we are destined to become”

I Am Doll Parts: The Fractured Anatomy of BREYER P-ORRIDGE and Pierre Molinier. By Emily Colucci. Filthy Dreams, October 10, 2014.

Pierre Molinier was a seriously strange fellow. For instance, he claimed to have had sex with his dead sister’s corpse and to have photographed it.

“Even dead, she was beautiful. I shot sperm on her stomach and legs, and onto the First Communion dress she was wearing. She took with her into death the best of me.”

Molinier’s bizarre fetish photographs represented a very intimate disclosure about his own sexuality and were considered absolutely outrageous for their time. (They’re still outrageous! It wasn’t easy finding a handful that would work on this blog without offending too many people.) Using himself as his primary subject, Molinier’s photo-montage art-form was often about depicting himself as a female (or hermaphroditic) alter-ego usually in the act of… well, auto-fellatio or doing it to him/herself in other creative ways.

Using masks, hand-carved dildos and prosthetic limbs, Molinier’s work was done mostly for his private pleasures starting in the early 1950s, but eventually he sent some of his pieces to Andre Breton who showed the work in 1956, thereby placing Molinier in the Surrealist camp. Early attempts to publish his work were made difficult by printers being reluctant to handle it and were abandoned. Eventually several monographs were published and slowly over the years Molinier’s work has become known to a cognescenti particular about such matters.

In the 1970’s, his health began to falter. Molinier committed suicide while masturbating, shooting himself in the head in his apartment in Bordeaux in 1976.

Below, this strange little animation takes Molinier’s work as a point of departure. Much more chaste than Molinier’s own work, you might want to watch this first before you decide if you want to go any further…

Molinier is my revolution. Tom de Pékin.

Long maligned and marginalised as a pervert of the artistic underground, Pierre Molinier is now recognised as an important Surrealist erotic painter, a fetishist photographer par excellence, a precursor of body art, and a pioneer of the queer movement. All his life he was a pleasure-seeker, fully focused on achieving his passions – anything rather than become a slave to convention.

Molinier grew up in the town of Agen in south-western France. At 22, after his compulsory military service, he moved to Bordeaux, earning his living as a house painter, and in his spare time painting landscapes and portraits in a fairly conventional style. He was a member of the Société Bordelaise des Artistes Indépendants (Bordeaux Society of Independent Artists) from 1928, and exhibited regularly in its salons.

Although already identifying as bisexual and transvestite, in July 1931 he married Andrea Lafaye, and they had two children, Françoise and Jacques. The relationship became ever more fraught; by the end of the 1930s Molinier moved permanently into a tiny studio apartment, where he spent time with a variety of lovers, and he and Andrea finally divorced in 1949.

After World War II, Pierre Molinier definitively rejected his previous life: he spent more time cross-dressing, painted increasingly provocative paintings, and started to take photographs of himself in sexual poses, often wearing stockings and corset. He was a man, but he also wanted to be a woman.

For the 1951 Salon des Indépendants, Molinier submitted ‘Le grand combat’ (The Great Confrontation), a half-abstract, half-figurative painting depicting contorted bodies and entwined limbs. The Bordeaux society deemed it indecent and censored it, which elicited a furious response from the incensed artist.

In early 1955 Molinier sent reproductions of his paintings and poems to André Breton, who gave him an enthusiastic welcome, assured him of his support and offered to exhibit him in Paris. Subsequently, Molinier designed the cover of the second issue of the magazine Le Surréalisme même (Surrealism Itself) then, invited by Breton, exhibited a canvas at the eighth Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme. Molinier was a member of the Surrealist group from 1955 to 1969, but remained on the fringes of Surrealism. Although close to Breton, and even more so to the anticlerical and antimilitarist painter Clovis Trouille, Molinier rejected most of the Surrealists, who were too puritanical for his taste.

Pierre Molinier was deeply influenced by the fields of esotericism, magic and shamanism, the character of the shaman arousing his interest because of its ambiguity, neither man nor woman, the messenger between the world of the living and that of the dead. From the mid-1950s Molinier devoted himself to photography, a medium in which he explored his subconscious transsexual desires. He created black and white photographs in which he assumed the roles of dominatrix and succubus previously assumed by the women in his paintings. He wanted his photographs to shock.

In the 1970s his health began to decline. He had told his friends that on the day ‘my sperm turns to water and I am unable to orgasm’ he would take his own life; true to his word, when his doctors informed him that he was suffering from prostate cancer he took his own life with a Colt 44 bullet to the head.

Pierre Molinier, 1900 – 1976. honesterotica, March 3, 1976.