As my

wife Jocelyne and I were utting the

finishing touches on Aline and Valcour (1795), a neglected masterpiece by the

Marquis de Sade never before translated into English, we learned of Jeffrey

Epstein’s allusive fascination with our infamous author. In the wake of

Epstein’s 2019 indictment for sex trafficking, journalist Vicky Ward recalled

how, in his mansion on 71st Street in Manhattan, the multi-millionaire, even as

he drank nothing stronger than Earl Grey tea, kept on display, among more

extravagant possessions, a paperback copy of Sade’s Justine, or the Misfortunes

of Virtue (1791).

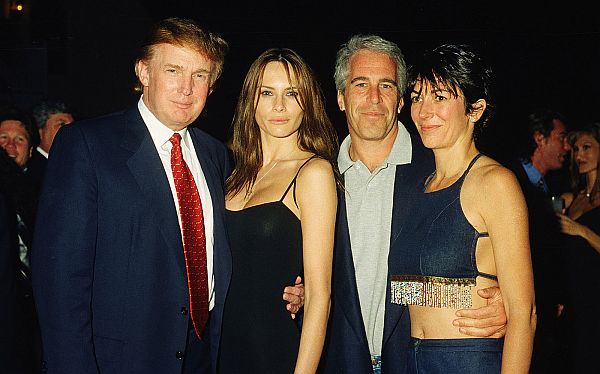

At first, we shrugged. A chasm separates the image of Sade as a raging woman-hater and sadomasochist, which abides in the popular imagination, from the more complex and discerning way he’s perceived in the politico-literary and academic worlds. But as the Epstein story evolved before its dramatic full stop with his strange death by hanging in a federal prison cell, we looked again. A hedge fund financier from nowhere, he’d sought clients exclusively among billionaires, counting as friends Prince Andrew, Bill Clinton, and Donald Trump, not to mention exalted executives at JP Morgan Private Bank. A host of notables glittered in his Little Black Book.

Such associates, with all due respect, placed him squarely in Sade territory. Epstein and his friends were just the sort of people the Marquis de Sade targeted in the famed opening sentence of The 120 Days of Sodom, the most impure tale ever written (penned in 1785, it was not published until 1904). Today’s endless wars, vivid disparities of wealth, banking crises, and soaring stock markets amid overloads of public debt can only lend renewed currency to these words:

The extensive wars wherewith Louis the XIV was burdened during his reign, while draining the State’s treasury and exhausting the substance of the people, nonetheless contained the secret that led to the prosperity of a swarm of those bloodsuckers who are always on the watch for public calamities, which […] they promote or invent so as, precisely, to be able to profit from them the more advantageously.

Fast forward 200 years, and that’s a pretty good description not only of Epstein and his friends but of the cultural trajectory of the 21st century.

Sade’s new moment has been building in the wake of our counterfeit Enlightenment and Panglossian dreams dashed. Where went the best of all possible worlds? Sex trafficking takes place on a grander scale than ever imagined, enticing the unrelenting libidos of poor immigrants and wealthy owners of football franchises alike. Sade would be gratified and amused, not shocked, to witness clergy scandals of such unprecedented scope as we see today; he both chronicled and mocked them in his novels. Our high-tech media have mounted an electronic stage for the visual display of cruelty in cultures and nation-states throughout the world, including our own. Guerilla and state-sponsored terrorism are joined by widespread nativist discourses and political leaders who target the helpless and impoverished — with the rise of Donald Trump being only the most prominent example of a worldwide phenomenon.

In the

daily press, Sade has often been held to reckoning for misogyny, owing to his

sexual excesses. There were plenty of them, in both his life and art. But he’s

also been frequently described as an avatar of liberty and, moreover, a

feminist at heart and before the name. A contemporary of Mary Wollstonecraft,

he shared her views on the education of women — quite unlike Voltaire,

Rousseau, or even Diderot. Long ago, French academic Alice Laborde, who taught

for years at UC Irvine, noted how advanced Sade’s views were concerning women’s

equality before the law. Although he should not be sugar-coated, Sade was not

the vile misogynist of popular fantasy. In his most scandalous novel, Juliette

(1797–1801), the Society of the Friends of Crime is dominated (to the chagrin

of some monsters) by women (also monsters).

Women,

in fact, have been among Sade’s most acute readers and literary theorists ever

since the 1950s, when he was unshackled from the censors, beginning with Simone

de Beauvoir’s “Must We Burn Sade?” (1951–’52) and, a generation later, Angela

Carter’s The Sadeian Woman (1978) and Camille Paglia’s Sexual Personae (1990).

Those are probably the best-known literary studies in English, but there have

been a good many others. Annie Le Brun, who edited Sade’s collected works, has

created over several decades a poetic-critical body of work around his unique

way of thinking. Francine du Plessix Gray, who died last year, published a

measured biography, At Home with the Marquis de Sade, in 1998. In academia,

Carol Warman and Natania Meeker have sought to clarify Sade and his place in

the Enlightenment literary pantheon. There are others.In France, Sade has become a “classic” author, his novels enshrined in bible-paper Pléiade editions. He’s become “an institution,” writes Catherine Golliau, “a source of interminable commentary and research in the university.” Why Did the 20th Century Take Sade Seriously? is the title of one recent (2011) book, by Éric Marty. Another is Khomeini, Sade and Me (2016) by Abnousse Shalmani, an Iranian woman, who states simply: “To read Sade is to grow up.”

We began

translating Sade’s epic and beautifully constructed novel Aline and Valcour a

long time ago. It started amid other projects, and we weren’t sure it would

work out. At a distance of more than a decade, I’m almost surprised we

persisted. The enterprise depended on a personal turn of fortune. About 2004 we

were priced out of our rambling floor-through apartment in Park Slope,

Brooklyn. We put our belongings in storage and, thanks to a friend, went to

live in a comfortable summer home overlooking Apple Canyon Lake in the Midwest.

Our postal address was Apple River, Illinois.

We

arrived in the winter with icicles on the trees. We stayed a couple of years.

Cherry blossoms accumulated on our doorstep in the spring. On summer days,

speedboats dragging inner tubes would trail-buzz screaming children across the

lake. With few neighbors we became the friends of nobody except the woodpecker

who pecked on the tin chimney, a swarm of nightly bats (there was a bat house),

a family of prairie dogs, and an owl who swooped down on her prey from a tall

fir. We were isolated and didn’t see anybody except each other for months at a

time. Friends joked: we should lock up the knives. We went out together daily

and bought food, wine, and London gin. Sometimes we took an exciting trip to

Dubuque, Iowa, to have our hair cut at the Capri College Beauty School. In

nearby Galena, Illinois, we found a beautiful old Carnegie Library at which, we

were told, we were about the only patrons. We translated for a multi-volume

encyclopedia of psychoanalysis and for a grand compendium of 20th-century

European history. From Sigmund Freud’s instinct theory and the narcissism of

small differences to two World Wars and the Holocaust, this sort of stuff was

good preparation for Sade.

That

project began in earnest when we returned to New York, ensconced on Staten

Island (of all places) in a series of apartments by turns infested and ugly,

spacious and ugly, old and ugly, and at last beautiful — all next to the

proletarian ferry. Jocelyne had read Aline and Valcour as early as 1995, when

she found a beat-up copy at the Brooklyn Public Library. “It’s like Marx before

Marx,” she told me. She was taken with Sade. As to misogyny in the novel, she

claimed there was none. Rather, owing to Sade’s personal magnetism, in evidence

200 years after his death, Jocelyne said then, and says today, that she’d

gladly die in his arms.

Aline

and Valcour was surprising and compelling, she added. “C’est un tourneur de pages.” There was talk of injustice and

religion, but overall it was an absorbing read, with characters and voyages

spanning the globe. I’d known about the novel since the 1980s, when I first

began with Sade, but only from a gloss by anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer. I

hadn’t read a word until Jocelyne started sending me, by email, files of the

first letters in translation. Ostensibly an epistolary work, the story consists

of 72 letters, beginning with love missives and promises of undying devotion on

the part of the title characters. However, by the time you reach the second

paragraph of the first letter on page one, you know it’s Sade. Enter the

egomaniacal antagonist: a magistrate judge who defends torture and asserts his

right to marry off his daughter to his bosom friend while concealing a further

agenda that is unspeakably vile.

The

rhythm for translating Marquis de Sade must be slow and forgiving, unbeholden

to deadline. The pace of Aline and Valcour varies greatly. It’s often quite

rapid but at other times philosophical and cerebrally intense. Fifty years ago,

Austryn Wainhouse, who put Sade’s most sulfurous texts into English, learned

the same thing. He spent 10 years translating Juliette and Justine. “Sometimes

it happens that reading becomes something else, something excessive and grave,”

he wrote. “[I]t sometimes happens that a book reads its reader through.” With

this novel from 1795, the same was about to happen to us.

Though not overtly pornographic, Aline and Valcour nevertheless bristles with sexual themes and is punctuated throughout with blasphemy. Not to give away spoilers but, for example, the two main antagonists are vicious libertines who carry on parallel affairs with two sisters whom they contrive to impregnate simultaneously, in order to raise their offspring in secret until about age 13, whereupon they would be turned into what today would be considered sex slaves — enjoyed, moreover, in an arrangement of reciprocity. Those problematic intentions furnish the novel’s first major plot point for a clutch of interwoven stories that send some of the 60-odd characters scrambling across great swathes of the known world.

But

politics writ large underlies the novel as a whole. Although sex is never far

from Sade’s mind, his main themes include political and religious domination,

crime and punishment, class conflict, and colonial conquest. Resonance with

contemporary fracture lines is ever-present, and so too is what Jonathan Israel

has called the Radical Enlightenment. In Sade, unlike Voltaire and Diderot, you

can’t find antisemitism (in fact, the reverse) or racial denigration, and at

one point he even brings up the issue of reparations for racial harms. He

describes a utopic South Seas island where all property belongs to the state

and there are no prisons and no death penalty. By contrast, there’s also a

dystopic society set in an as-yet-unexplored Africa that strikingly prefigures

Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899).

Sade

wrote Aline and Valcour while imprisoned in the Bastille, the medieval fortress

turned jail in the middle of Paris. He was held at the king’s pleasure, without

formal charges, at the behest of his mother-in-law. Although friendless at the

court of Louis XVI — he avoided Versailles with studied disdain — he belonged

to the ancient aristocracy, to which he owed his rock-star infamy for sexual

excesses and blasphemies. It was one thing in the 18th century to whip a

prostitute, another to spit and trample on the cross. He had been constantly in

trouble, imprisoned, and was indicted for poisoning and sodomy. Those were

capital crimes. Convicted by a regional court in absentia, having skipped the

country, he was executed in effigy on September 12, 1772 — that is,

ceremonially beheaded and burned, his ashes scattered. That conviction was

eventually overturned on appeal, but the symbolic execution resonated in his fiction.

Scaffolds, he wrote, were like boudoirs. “Pronouncing the death sentence,” he

insulted the judges in Juliette, “your pricks harden; and you discharge when it

is carried out.”

Jocelyne

and I were not ceremonially strung up or drawn and quartered when we started

translating Aline and Valcour. But that could qualify as an aspiration so far

as right-wing activist and syndicated columnist L. Brent Bozell was concerned:

after the National Endowment for the Arts awarded us a grant, Bozell criticized

the organization for using taxpayer dollars to encourage translation of a book

by, of all people, the Marquis de Sade. Bozell’s so-called news company,

CNSNews, awarded the NEA the Golden Hookah Award for funding the translation.

What were we smoking? Gitanes? Gauloises?

Most of

Aline and Valcour — not just the best parts, in fact — Jocelyne and I

translated together in bed. It was the ideal place to reconcile my edit of her

first draft. We were inspired by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, the

husband-and-wife team that collaborated on celebrated editions of Tolstoy and

Dostoyevsky. They work similarly, though perhaps not horizontally. But they

would not have faced exactly the same set of issues. Oh, they might have wept

together when Anna casts herself beneath the wheels of a train. We were

relieved, by contrast, when Léonore escapes death by impalement, after her

executioner strips her naked to reveal “the particular part of the body which

Nature locates beneath the small of the back.” At this juncture (despite the

persistence of capital punishment in the United States), we felt compelled to

add an endnote explaining that impalement was indeed “traditionally performed

as Sade indicates, with insertion of the pike through the anus and extrusion

through the chest cavity.” Sade’s insistence on the centrality of the body in

connection with justice is on display throughout Aline and Valcour.

Léonore,

who is saved before the axe falls, turns out to be the novel’s greatest

surprise. This 17-year-old narrator has been largely ignored in the sparse

critical commentary on the book, although Beatrice Fink noted 40 years ago that

she “is clearly the focus of the novel and the key to its unity.” Léonore is

young, beautiful, and well read. She faces adventure and a host of physical and

mental challenges that keep her constantly reflecting on men and the societies

they create. After eloping with her lover, she is abducted by a vicious

libertine, sped across the ocean trapped in a coffin, enslaved and sold to

pirates, almost beheaded by an Egyptian king, and nearly eaten by a cannibal.

But her charm, cleverness, and sardonic wit are ever-present. The only reason

she faces death by impalement has to do with a bit of lèse-majesté: she and her

fellow travelers, reaching Sennar in the Sudan, are inveigled into visiting a

forbidden shrine where Muhammad’s organ, preserved across 10 centuries, may be

viewed; off they go as if to some out-of-bounds museum exhibit, only to be

waylaid and brought before a heartless king.

But

there’s more. Léonore has been traveling in disguise, and the moment of her

execution has a crazy but startling contemporary angle. The king who wants to

watch her die is a narcissist given to ostentatious displays of wealth. He both

revolts his subjects and is afraid of them. As the executioner seizes Léonore

and strips her naked, the crowd gathered to watch suddenly realize that she’s

not male but female. And she’s white, not black — in fact, two-toned, with her

body painted above the waist. When her true gender and skin color are revealed,

the crowd erupts and scatters as “some took me to be a god, others, the devil.”

Léonore is spared. Naturally the king now wants to fuck her before killing her.

But she escapes and continues her trans-African journey — LGBT-certified, as it

were.

Of

curious note for American readers, the story of Léonore (which takes up a good

portion of the novel, about 300 pages) bears uncanny similarities to that of

Huckleberry Finn. The basic trajectory is a picaresque road trip, during which

she acquires a companion — a Spanish beauty, Clémentine, who is as capable a

philosophical interlocutor as Twain’s Jim. Being women, persecution and

domination are the constant dangers they face. After escaping a would-be

husband in Alexandria, Léonore joins a caravan that takes her through Ethiopia.

In uncharted Africa, she contends with a cannibal king, eventually escaping his

thrall; trying to return to France via the Iberian Peninsula, she and

Clémentine find themselves robbed and penniless in Portugal, and are adopted by

a band of Romanian gypsies before they fall afoul of the Spanish Inquisition.

She goes on to dupe the Grand Inquisitor himself.

Léonore,

the only admitted atheist in the book, is a proto-feminist. Her sardonic wit

counters the goodness, godly devotion, and melancholy of the title character,

Aline. Unwilling to become a victim, Léonore is the novel’s face of liberty.

You don’t always like her, but she’s impressively clever.

There’s

much more to Aline and Valcour’s 800-plus pages. Sade wrote his books on the

eve of an immense transformation of the world, and the imminence of colonial

and imperialist expansion is in evidence throughout. Characters embody various

shades of Enlightenment thinking, from counter- to mild to moderate to radical.

But they also stand up as three-dimensional figures in ways that cannot be said

of most of the characters in Sade’s pornographic texts. The conclusion — the

last 100 pages, in fact — enters territory later explored by Stendhal, crossing

romanticism with nascent realism. By the novel’s end, Sade has become an author

you never imagined. Wrangling his words into English, we were persistently

surprised when one of his tragic themes played out with delectable detail,

dialogue, and description. When later we learned that Stendhal used Sade to

help formulate his long discourse on love, it came as no surprise at all.

At several key moments in modernity’s transit, and now again today, the Marquis de Sade’s writings and thought have been inserted into the wider realms of social and political discourse. After his death in 1814, his works were officially banned, and he cropped up principally in the poetics of mordant souls like Baudelaire and Flaubert. But he made a real return in the wake of the slaughters of World War I by way of the Surrealists, who fomented a revolution in aesthetic politics. After World War II, Sade enjoyed another moment, as his novels were understood to prefigure the even more flagrant atrocities of the Holocaust. He had understood, as so many others did not, that reason would be put to use torturing and murdering people on an industrial scale. A generation later came the multifaceted sexual revolution of the 1960s, and Sade arrived equipped with his erotic manifesto, Philosophy in the Bedroom (1795). His works, no longer banned, were translated and published internationally, and Sade became a seminal figure in the pantheon of French literature, a philosophe to contend with in Enlightenment studies, and an inspiration to contemporary thinkers, from Lacan and Barthes to Derrida and Foucault.

In the

words of Natania Meeker, a professor of French and comparative literature at

USC, the world Sade depicts is one we all recognize: “[A] social order that

both fetishizes greed and subjects all creatures, humans included and not

excepted, to a relentless logic of acquisition and possession.” That logic was

visible in the life and death of Jeffrey Epstein, in the way he extracted

massages from hebetic beauties while sparing no expense in equipping hedge-funded

islands and Fifth Avenue mansions. His urge for acquisition was not limited to

sex trafficking or sybaritic self-indulgence. He sought to purchase more than

perpetual onanism. He had big ideas that he spelled out in fuzzy letters for

any eminent scientist or wealth manager who would listen. He fantasized a

bio-social future for himself and his penis, an organ he hoped to have

literally frozen in time, to be used to impregnate scores of nubile women at

Zorro, his ranch in New Mexico. All in the interest of germline engineering

(eugenics by another name), in order to perpetuate himself eternally.

Epstein is a reminder that we (in that highly limited sense in which we are ever a we) are more vulnerable today than ever before to the insanities of wealth. Whether it be his transhumanist fantasies, or the climate change denialism funded by the Koch brothers, or the anti-liberal conspiracies nurtured by Richard Scaife, or the self-serving, diversionary philanthropy of the Sackler family, big money can purchase and promulgate delusion. The Trump presidency has been delusion incarnate. How long it can be sustained is anyone’s guess. That “swarm of bloodsuckers” Sade described 200 years ago is still attached to the flesh of the body politic. The last prisoner of the Bastille had their number, and his scabrously brilliant writings can open your eyes to their poisonous dreams in a way no muckracking journalistic exposé could ever hope to do. Seriously.

The first English translation of Marquis de Sade’s 1795 novel Aline and Valcour, by John Galbraith Simmons and Jocelyne Genevieve Barque, was published in three volumes by Contra Mundum Press in December 2019.

Sade, Too: A New Moment for a Complex Monster. By John Galbraith Simmons. Los Angeles Review of Books, April 1, 2020

The recent publication of two works by the Marquis de Sade enables us to see that sadism is not just “the impulse to cruel and violent treatment of the opposite sex, and the coloring of the idea of such acts with lustful feelings,” as Richard von Krafft-Ebing defined it in his 1886 Psychopathia Sexualis. Sadism, as it is depicted by Sade, is also, and perhaps primarily, the creation of a world in which the powerful and wealthy are able to lure the poor and powerless, hold them captive, and reduce their bodies and selfhoods to nothing.

In this,

as some clear-sighted post–World War II writers have noted, Sade’s writing was,

inter alia, a harbinger of fascism. Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, for

example, wrote that Sade “prefigures the organization, devoid of any

substantial goals, which was to encompass the whole of life” under the

totalitarianism that drove them from Germany. Reading Sade in the age of #MeToo

and Jeffrey Epstein is an uncanny experience, for his novels are also a blueprint

for the world of the sexual predators of today.

This

winter brings the first complete English translation of Sade’s vast epistolary

novel, Aline and Valcour, in a lavish, three-volume edition from Contra Mundum.

The translation, by Jocelyne Geneviève Barque and John Galbraith Simmons, is a

masterful one, allowing Sade’s prose to flow, neither assuming the language and

rhythms of the eighteenth century nor interpolating anachronisms from English

today. It is, by all appearances, the work of two people who have studied the

writing of Sade deeply and admire it.

Originally

published in 1795, Aline and Valcour was, according to its title page, “Écrit à

la Bastille un an avant la Révolution de France”—“Written in the Bastille,”

where Sade had been held since 1784, “one year before the French Revolution.”

The novel stands out from almost every other novel in Sade’s oeuvre in that it

is not a work of pornography, though it does not lack for libertines and

salacious events. It’s a grab-bag of a book, filled with tales within tales

that take the reader to Africa, Portugal, and Spain. Not only is it not

pornographic, but it is also a novel in which many of the ideas expressed run

counter to those that were central to Sade’s thought.

Sade

explains this in a footnote, writing that Aline and Valcour “offers in each

letter the correspondent’s own way of thinking or that of the persons involved

and to whom he offers his ideas.” If, unlike the rest of Sade’s work, this

novel is not solely in his voice, it is because, as the translators explain in

their introduction, the author intended to present the range of views held by

Enlightenment thinkers, whether he shared them or not. The result is a book in

which religion and motherhood, both of which Sade mocked and detested, are

praised, and where nature, which Sade viewed as an amoral force that served to

explain and justify his characters’ evil, is presented as beneficent.

The

first French dictionary to include the word “sadism,” in the mid-nineteenth

century, defined it as “a monstrous and anti-social system revolting to

nature.” That being so, nothing could be further from Sade than this novel by

Sade.

The 120

Days of Sodom, a new translation of which was published as a Penguin Classic in

2016, is another matter entirely. The manuscript of this, the most notorious of

Sade’s books, was thought lost when Sade was transferred from the Bastille to

Charenton a few days before the prison was stormed on July 14, 1789, and didn’t

receive its first French publication until 1904. The challenges that its

translators, Will McMorran and Thomas Wynn, faced were far different from those

of Barque and Simmons, for McMorran and Wynn’s task was to translate a book

that summarizes the Sadeian worldview in all its fury, in all its madness.

It is a

work of brutal pornography interspersed with occasional bursts of Sade’s

philosophy, a mélange of borrowings from Montaigne’s cultural relativism, Jean

Meslier’s atheism, La Mettrie’s materialism, and d’Holbach’s materialist

atheism. These philosophical outbursts are sprinkled among countless pages of

coprophagy, flatulence, and vomiting (all for erotic purposes); of sodomy and

misogyny. Both the content and the worldview expressed in The 120 Days of Sodom

make it as close to a repellently unreadable book as has ever been written.

This new

translation also happens to be a clumsy one, full of odd and poor choices, the

worst of which is a character’s exclaiming, “Golly, sweetheart.” But the

infelicities of the translation are of relatively minor concern. The 120 Days

of Sodom most clearly poses the problem of Sade’s survival. How has this body

of work continued to be read, let alone enjoyed the status of a classic?

Sade,

though admired by Flaubert, among others, was, in fact, a figure of little

literary consequence until the early twentieth century, when Guillaume

Apollinaire rescued him from oblivion, by publishing in 1910 a collection of

his novels. Apollinaire proved himself a seer when he wrote in the introduction

to his edition that “this man, who seemed to count for nothing for the entire

nineteenth century, could very well dominate the twentieth.”

In the

century after Sade’s revival, a shocking number of intellectuals fell under his

spell, explicated him, and defended him. Their focus was almost always on the

philosophy of Sade, on the “transvaluation of values” he performed that would

have made Nietzsche blanch. Sade the stylist hardly figures in the commentaries

written by his admirers; indeed, it would be hard to make much of a case for

writing that is verbose, repetitive, and, for all its sexual explicitness,

impoverished. Added to these faults is the sheer bloat of his books: La

Nouvelle Justine is 720 pages in the definitive Pleiade edition; L’Histoire de

Juliette, 1081 pages; and the new translation of Aline and Valcour, 819

pages.

Nevertheless,

Apollinaire set the intellectual template for those who would follow, claiming

that “above all, [Sade] loved freedom. Everything—his actions, his

philosophical system—testified to his passionate taste for the freedom he was

so often deprived of.” Roland Barthes in 1971 upped the stakes in his

Sade/Fourier/Loyola, calling Sade “the most libertarian of writers”—a

declaration that failed to take account of how, in his supposed “love of

freedom,” Sade placed severe limits on the liberties of others, both in his

books and in his life. “If one of you should suffer the misfortune of succumbing

to the intemperance of our passions,” wrote the great “libertarian” in The 120

Days of Sodom, “let her bravely accept her fate—we are not in this world to

live forever, and the best thing that can happen to a woman is to die young.”

Like a

guard in a concentration camp, the Sadeian hero is allowed absolute freedom to

do whatever he likes to his victims, who are in most cases kidnapped or

purchased and imprisoned in castles or chambers from which no escape is

possible. In one of many instances that appear to foreshadow the fate of those

imprisoned in the Nazis’ camps, Sade wrote, in The 120 Days of Sodom, “Here you

are far from France in the depths of an uninhabitable forest, beyond steep

mountains, the passes through which were cut off as soon as you had traversed

them; you are trapped within an impenetrable citadel.” Even more directly, in a

passage from Juliette quoted by Adorno and Horkheimer in their Dialectic of

Enlightenment—where they wrote that we find in Sade “a bourgeois existence

rationalized even in its breathing spaces”—Sade wrote: “The government itself

must control the population. It must possess the means to exterminate the

people, should it fear them… and nothing should weigh in the balance of its

justice except its own interests or passions.”

Apollinaire

was first followed by the Surrealists. In 1926, Paul Éluard praised Sade in the

movement’s organ, La Révolution Surrealiste, writing that “for having wanted to

infuse civilized man with the power of his primitive instincts, for having wanted

to free the romantic imagination, and for having desperately fought for

absolute justice and equality, the Marquis de Sade was imprisoned almost his

entire life in the Bastille, Vincennes and Charenton.” André Breton went even

further, saying in a 1928 discussion of sexuality that, “By definition

everything is allowed a man like the Marquis de Sade, for whom the freedom of

morality was a matter of life and death.” We get an idea of Sade’s notion of

“absolute justice and equality” in The 120 Days of Sodom, where he wrote:

“Wherever men shall be equal and where differences shall cease to exist,

happiness too shall cease to exist.”

Some of

this affection on the part of the Surrealists for the “divine marquis” can be

written off as provocation, the avant-garde desire to épater le bourgeois. But

Sade’s novels seemed to them a guide in their search for a new mode of being

that escaped all and any limits. It was precisely the extent that Sade violated

all taboos, social and sexual, that made him a member of their pantheon. But in

elevating Sade, the Surrealists had no choice but to read him selectively, to

elide the terror that this supposed ethic of personal liberation imposes on

others. The freedom of the one existed at the price of the oppression of everyone

else, of their reduction, in fact, to mere orifices.

Then, in

the aftermath of World War II, there was an extraordinary explosion of analyses

of Sade. Pierre Klossowski, in his 1947 Sade, mon prochain, claimed that Sade

was a man deeply influenced by Christian mystics. In a 1951 article in Les

Temps modernes, Simone de Beauvoir famously asked: “Must We Burn Sade?”

Answering in the negative, Beauvoir was not reticent in pointing out the flaws

and contradictions of Sadeian thought. Warning against a “too easy sympathy”

for him, she wrote, “it is my unhappiness he wants; my subjection and my

death.” Still, she concluded by enlisting him in the Existentialist cause,

saying that: “He forces us to put in question the essential problem that haunts

this time in other forms: the true relationship between man and man.”

Georges

Bataille, however, viewed the matter very differently in his 1957 L’Érotisme.

For Bataille, Sade’s theme is the isolation of the subject. The sexuality

expressed in his books excludes the possibility of any real contact, and the

people with which he and his characters engage “cannot be partners, but

victims.” Even more, his literature portrays the image of “a man for whom

others cease to exist.”

Roland

Barthes provided an answer to the question of whether Sade must be burned by

sheltering behind “discourse.” The “sole Sadeian universe” is that of “the

universe of discourse.” Any offense taken at the acts in Sade’s novels is

unjustified because it fails to take account of the “irrealism” of his books.

“[W]hat happens in a novel by Sade is strictly fabulous, i.e., impossible.” To

condemn Sade’s books is to fall into the trap of “a certain system of

literature, and this system is that of realism.”

But the

notion that Sade was a purveyor of “irrealism,” that his life had nothing to do

with his novels, does not stand up to scrutiny. The difference between the

crimes he committed in life and those he depicted in his novels is one of

degree and not of kind. In 1768, in the Parisian suburb of Arcueil, Sade

induced a beggar, Rose Keller, to accompany him home, promising her a job as a

housekeeper. When they arrived at their destination, Sade threw Keller onto a

bed, tied her to it, whipped her until she bled, sliced her skin with a

penknife, and dripped hot wax on her. Though she filed a complaint and he was

briefly imprisoned, family influence resulted in his release.

Four

years later, in Marseilles, Sade sent his valet to recruit what a biographer

called some “very young” girls for a debauch. In the end, seven people would

participate in the event, the young women whipped and at least one of them

sodomized, and the victims drugged with Spanish fly. This abducting of young

girls with whom he would have sex, and his locking of victims in castles so

they could not escape his desires, occurs in all of Sade’s novels, turning

them, on the contrary, into realist, even autobiographical, fiction.

Imprisoned

for the Marseilles escapade, Sade would escape, and within three years he found

himself involved in yet another sexual scandal. He was finally imprisoned in

1777 under a lettre de cachet, a royal order for arrest without trial, obtained

by his mother-in-law to protect family honor against any further criminal sexual

exploits. Sade would remain imprisoned until the Revolution abolished the

lettre de cachet in 1790. Arrested again in 1801, under Napoleon, and held at

Sainte-Pélagie prison, Sade was transferred to the asylum at Charenton in 1803

after attempting to seduce fellow inmates at Sainte-Pélagie. It was in

Charenton that he organized the theatrical productions immortalized by Peter

Weiss in his 1963 play Marat/Sade, and where Sade would die in 1814. While in

the asylum, at age seventy-four, in what a biographer called “his least

glorious phase,” he regularly sodomized (for payment and with her mother’s

consent) a young woman of sixteen, Madeleine Leclerc, noting the frequency of

his acts in a journal.

Not all

postwar intellectuals fell under the sway of the divine marquis or saw him as

simply a philosopher who lived his ideas in a more extreme way than others.

Some saw the fascism latent in his novels—and said so explicitly, as Raymond

Queneau did in 1945: “all who embraced the marquis’s idea to one degree or

another must now envision, without hypocrisy, the reality of the death camps,

with their horrors no longer confined within a man’s head but practiced by

thousands of fanatics.” Camus noted in The Rebel, published in 1951, that the “ideal society” constructed by Sade

“exalted totalitarian societies in the name of liberty.” And it was the

cinematic provocateur Pier Paolo Pasolini who presented the connections between

Sade and fascism most starkly of all in his final film, the 1975 Salò or The

120 Days of Sodom); there the book’s brutalities are enacted under the flag of

Mussolini’s Social Republic.

Sade’s

attraction for some has nevertheless persisted—as the most extreme example of

counter-Enlightenment thought, the voice of the abolition of reason. It was,

after all, the very impotence of reason that was made so starkly and

horrifyingly manifest in the two world wars and the period between. Sade’s

exclusive concern with the sovereignty of the individual, on an absolute

freedom from any constraint, continued to lure a certain class of intellectuals

in a period of mass politics. In Weiss’s Marat/Sade, the two historical figures

embody the most radical expressions of these dichotomous forms of rebellion:

the political and the individual. As Beauvoir wrote of him, “Sade supposed

there could exist no other road than that of individual rebellion.”

This was

his weakness, but it was also a source of his enduring appeal. And so, Sade

survived. But can his oeuvre survive our own time? And should it?

It is

impossible not to think of Jeffrey Epstein and his accomplices when reading

Sade. In The 120 Days of Sodom, the age of the girls delivered to the

libertines “was fixed between twelve and fifteen and anything above or below

was ruthlessly rejected.” And in Aline and Valcour, two libertines “keep a

seraglio of twelve young girls… of whom the oldest is not yet fifteen, and is

replaced at the rate of one a month.”

Epstein’s

plane was flippantly and familiarly known as the Lolita Express; in one

reported incident, a twenty-three-year-old woman brought to him was rejected as

too old. Like Sade, Epstein had hirelings to procure his victims. The

financier’s procuresses lived well, as did those in Sade’s work, who in 120

Days received “thirty thousand francs—all expenses paid—for each subject found

to their liking (it is extraordinary how much all this cost).”

The

libertines in Sade, to quote Barthes, also “belong to the aristocracy, or more

exactly (and more frequently) to the class of financiers, professionals, and

prevaricators.” And like the victims of Epstein, those victimized and assaulted

by Sade’s characters in his fiction, as by Sade himself in real life, “belong

to the industrial and urban sub-proletariat.” The power differential that plays

such an important part in the contemporary scandals is limned in the biography

and writing of Sade. It was Camus who summed up the Sadeian universe as one of

“power and hatred,” a term just as aptly applicable to Epstein’s world.

Epstein’s

Caribbean island, to which young women were flown, his ranch, and his townhouse

are a contemporary version of the castles in which Sade’s fictional and actual

victims were assaulted. Just as in the case of Sade, where the will of the

victims was ignored, their lives reduced to obeying the libertines’ orders,

Epstein’s girls were at times referred to as his friend Ghislaine Maxwell’s

“slave[s].” As the victims in the pages of Sade hear: “no one knows you are

here… you’re already dead to the world and it is only for our pleasures that

you are breathing now.”

According

to court documents, Epstein “required different girls to be scheduled every day

of the week,” just as 120 Days records the drawing up of a timetable to detail

which victim will perform which act on which day. Epstein’s regimen recalls

Sade’s character in Les Infortunes de la virtue who explains that “I make use

of women from need, the same way one makes use of a chamber pot for a different

need.”

Epstein

carried on with virtual impunity until the final reckoning, like the libertine

in Sade’s 120 Days who would “commit excesses that would have sent his head to

the scaffold a thousand times were it not for his influence and his gold, which

saved him from this fate a thousand times.” Sade’s books are a guidebook to,

and prophecy of, the Epstein case.

In one

important way, though, this looking-glass is reversible: it is Epstein who

illuminates Sade and allows us to read the French aristocrat with a different

eye. Sade lived his drives, and when imprisoned, he turned them into

literature. That literature is still read and is still the subject of serious

study. Some recent books, for example, have viewed Sade through the lens of

queer theory, examining his vision of sex and death, once again placing him

within the framework of Enlightenment thought.

But we

might justly ask: Had Jeffrey Epstein lived and become a writer, would his

literary output have enthralled us?

There is

no indication that Epstein ever committed to paper his ideas and fantasies, as

Sade did so obsessively. Sade, after all, viewed himself not just as a

libertine, but as a philosopher of libertinism (one of his works was titled

Philosophy in the Boudoir). His flights of fancy served to relieve the

privations of his confinement, perhaps, but they were also the basis for an

encompassing worldview like few others.

Unlike

Sade, Epstein did not elevate his tastes into a principle. And that Epstein

left no account suggests a consciousness of the legal jeopardy any such record

would create. But if Epstein had done so, would anyone have dared write of him,

as Breton did of Sade, that he was someone “for whom the freedom of morality

was a matter of life and death”? For both men, the freedom of morality was, in

actuality, a freedom from morality, a license to inflict pain on others.

There

are two nouns Sade uses heavily in his novels that sum up the Sadeian universe:

victime and scélérat, victim and villain. This is the only moral division of

any significance in his works—and it perfectly summarizes the worlds of both

Sade and Epstein. “Laws are null and void as concerns scoundrels,” wrote Sade,

“for they do not reach he who is powerful, and he who is happy is not subject

to them.” Both men acted and lived in accordance with that dictum.

If

Beauvoir was right and Sade forces us to question “the true relationship

between man and man,” then Epstein’s predations present us with an unalloyed

vision of precisely how money and power twist those relations. To change that

requires an utter rejection of Sade’s philosophical system, as succinctly

expressed in a line from Justine: “My neighbor is nothing to me; there is not

the least little relationship between him and me.”

We need

not burn Sade, but neither should we praise him. His spirit still wanders among

us, and we must use him to see why we have our Epsteins.

Reading

Sade in the Age of Epstein. By Mitchell Abidor.

The New York Review of Books, February 12, 2020

We’ve

come a long way. Novels by the Marquis de Sade, which (more than any of his

confessed violent crimes) ruined his life, are legal and easy to obtain. (Fanny

Hill, which is about as pornographic as an average fifth-grade darefest, wasn’t

fully legal until 1966.) At some point in our history, the 9th District Court

of Somewhere presided over a landmark court case where innumerable witnesses

swore that readers of banned books spend more time pursuing tenure than they do

committing unthinkable acts of erotically motivated homicide. Which is true.

By then,

of course, de Sade had already become a major inspiration for generations of

rebellious Continental types, especially those artists and philosophers who

were into decadence, surrealism, and the prolonged, deliberate misuse of Freud.

The list of such luminaries is far too long to include here, but I’m sure you

get the idea. I’ve stumbled across references to de Sade in all sorts of

academic literature, including The Pleasure of the Text by Roland Barthes, who

is a postmodern semiologist. In other words, he was paid to study what things

mean, even though he repeatedly concluded that nothing meant anything. In

France, which is more Catholic than you can possibly imagine, reaching such

conclusions is considered both difficult and heroic.

Barthes

can barely wait to start in on his comrade de Sade. The following passage

appears (suddenly, without warning) at the top of page six:

Sade:

the pleasure of reading him clearly proceeds from certain breaks (or certain

collisions): antipathetic codes (the noble and the trivial, for example) come

into contact; pompous and ridiculous neologisms are created; pornographic

messages are embodied in sentences so pure they might be used as grammatical

models. As textual theory has it: the language is redistributed. Now, such

redistribution is always achieved by cutting.

This is

definitely wrong, as anyone who tries picking up de Sade’s Juliette can tell

you. Juliette is approximately 1200 pages long. It’s a damn good thing it

stayed illegal for 150 years, because otherwise nobody would finish it. De Sade

did not sculpt a work of rigorous, concise, jagged pornography. He produced a

frenzied, garrulous, overwhelming torrent of obsessively repeated incidents and

themes. Nothing gets cut or boiled down. There’s no evidence of postmodern juxtaposition;

instead, de Sade writes with the naive confidence of the fetishist who thinks

everyone will understand him, even when his recipes for pleasure become

mind-bogglingly personal.

The

sentences are not pure, contra Barthes. While some of them could serve (for

who, exactly?) as “grammatical models,” others are pretentious and convoluted.

Barthes’ own reference to “pompous and ridiculous neologisms” attests to Sade’s

uneven, undisciplined prose; where Sade is at his most limpid, stylistically,

he’s simply imitating his era’s primers for schoolchildren. Nor is Sade

engineering collisions of the noble and the trivial; that had already been done

two centuries earlier, to perfection, by William Shakespeare. De Sade never

bothers with trivialities at all. Who are Juliette’s parents? What does her

nose look like? What’s her favorite color? We don’t know because de Sade

doesn’t care. His version of human nature removes every mundane wrinkle; in the

words of Tyler Durden, from the David Fincher movie Fight Club, de Sade “let[s]

what does not matter truly slide.”

This is

the reason why—despite what Barthes claims about Sade, all of which is far

truer of Barthes than his subject—he is basically right to put de Sade front

and center in a book about the reader’s bliss. De Sade is a towering figure in

any literary canon founded upon joy, for reasons at once enlightening and

complex. Let’s start with the obvious. De Sade couldn’t stop writing. After he

was arrested for publishing Juliette, he began composing The 120 Days of Sodom,

in miniature, on a tiny roll of paper he kept squirreled away in the wall of

his prison cell. This is the kind of behavior we reserve, in general, for the

most important utterances of our lives. That Sade would do this in order to

write yet another novel mixing pornography with philosophy is both ridiculous

and baffling. He has finished two novels that already overlap; he has nothing

substantial left to say; the content isn’t what’s driving him. What’s driving

him is his relationship with his ideal reader. He sacrifices everything that’s

his by right, including both freedom and libertinage, to that. This is the

first exciting thing about de Sade: when you read him, you become (by default)

the love of his life.

The

Marquis de Sade is also the first person to enjoy the deaths of minor

characters. You know how, when a minor character dies in a regular novel, you

have to feel some kind of court-appointed guilt? In Juliette, it’s not sad at

all. It’s a cause for celebration. It reminds me of one of my favorite

psychiatrist jokes. “Doctor,” a man tells his psychiatrist, “people all think

I’m nuts.” The psychiatrist replies: “So why don’t you kill them?” Now in real

life, you can’t go around killing people indiscriminately, because it’s

exhausting. It’s hard, thankless work. But Juliette is not real life. I can’t

emphasize this enough. Juliette can do whatever the fuck she wants. She loves

killing people, and I don’t blame her—other people are annoying as hell.

Reading de Sade is an experience in freeing your imagination. If doing that

seems immoral to you, then you’ll never dream up anything of consequence,

because you’ll never discover what it is you like.

Juliette

is also exactly as long as you want it to be. You can read it for 100 pages and

stop; you can read the whole thing; you can read five pages and give up. It’s a

fractal. Every experience of Juliette is absolutely identical to every other

experience of it, no matter how long or short. This is not only extremely

convenient; it’s intimately related to how perfectly fictitious everything in

Sade’s universe is designed to be. Nobody waits for gratification in Juliette,

and no endeavor encounters a serious obstacle. Juliette has no other content

besides pleasure. This isn’t true of other pornography. Other pornography has

tons of unnecessary content: “the plot is ludicrous,” as Maude Lebowski once

observed. People don’t strip off their clothing in Juliette; they walk around

naked. People don’t work their way to opulence; they’re bathed in it from

birth. If de Sade includes something, you better believe he thinks it’s

delicious. Perhaps you disagree; that’s well and good. It’s much more fun to

read about something in Sade, and find it disgusting or dull, than it is to

read about something disgusting or dull in another “erotic” novel and realize

it’s there because the author thought you’d like it. That’s both unpleasant and

insulting.

I’ll

conclude by touching, briefly, on the matter of de Sade’s excursions into

philosophy. These are famous for being “incongruous,” since they’re bookended

with orgies, and we don’t associate philosophy with orgies. (Centuries later,

Hugh Hefner would be hailed as a marketing genius for juxtaposing smut with

Norman Mailer interviews.) But just consider the double game that Sade is

playing when he puts such a text together. If you skip over the philosophical

digressions, you’re a shallow pervert who obviously loves a good orgy; if you

don’t, and willingly put off the orgy just to read about the nature of the

mind, then you’re even sicker, and there’s probably no help for you. In other

words, sex always means something in de Sade; there is no such thing as

“casual” sex in his writings.

Having

sex with a stranger, in de Sade, is (among other things) a declaration of war

on marriage. It’s a statement about what it means to be human. It’s a statement

about incomprehensible divine justice. It contains multitudes. Of course, Sade

also makes people scream out loud, “There’s more to life than sex!” Then they

go on to explain, to anyone within earshot, how important certain non-sexual

things are. In their frustration and their shock, they go into incredible

detail about how wrong Sade gets life, often reaching for a pen just so they

can get all their thoughts down on paper. Whatever happens next is their art,

their chosen antidote to reality.

Somebody

once said, speaking of The Velvet Underground & Nico, that almost nobody

bought it, but everyone who did started a band. Juliette’s pretty much the same

way. Because there’s more to writing, and to life in general, than Juliette, no

other book makes me quite as hungry to get out there, and write, and live, just

so I can prove that old lecher wrong. This would undoubtedly fill him with

delight.

Reading

Juliette, By the Marquis de Sade. By Joseph Kugelmass. Splice Today , November 11, 2019.

On 2

July 1789, a man whose official designation in the prison fortress of the

Bastille was ‘Monsieur Six’ addressed the people of Paris. He spoke – or

shouted – from his cell in the Tour de la Liberté, and in no uncertain terms.

The officials holding him, and the regime they served, were villains, devils,

criminals and worse. What’s more, they had already begun to slit the prisoners’

throats. There was no time to lose. That evening, the governor of the Bastille,

who had slit no throats, informed his superior that if Donatien Alphonse

François de Sade, whom 13 years of imprisonment without trial had done nothing

to mellow, were not removed from his prison that very night he could no longer

guarantee its security. His wish was granted and Monsieur Six was taken in the

night to a madhouse, where his screams would go unheeded. In the event, 11 days

later, the security of the Bastille ceased to be guaranteed when it was stormed

by a revolutionary mob.

The men

and women who had been massing outside the building for the preceding weeks at

last found themselves running through its halls (the governor’s severed head

had already been placed on a pike), unlocking door after door as they went.

Number six, untouched since its last occupant’s departure, was awash with

paper. There was a library of more than six hundred books, many of them rare,

and dozens on dozens of manuscripts in a Voltairean variety of genres (Voltaire

himself – a friend of Sade’s father – had twice been a prisoner in the

Bastille). There were so many manuscripts that their author had prepared a

catalogue raisonné to keep track of them: two volumes of essays, eight of

fiction, 16 historical novellas, twenty-odd plays, and much more work in

progress. Reading conditions were not favourable that night and by morning

virtually the whole oeuvre had been destroyed. For the remaining 25 years of

Sade’s life there was one loss that he mourned more bitterly than the rest.

This manuscript – which he had been careful to leave out of the catalogue – was

written in a small clear hand on both sides of a forty-foot-long roll of paper

hidden in a crevice of the cell’s 14th-century wall. When the fifty-year-old

Sade emerged from his madhouse on Good Friday the following year, the Bastille

had not only been stormed, it had been destroyed – burned down and carried

away, brick by brick. And so Sade naturally abandoned all hope for the

manuscript over which years later he still claimed to shed ‘tears of blood’.

Although

Sade was never to know it, his manuscript had survived that night, and every

night since: having been smuggled out of the Bastille it was handed down

through three generations of one French family before appearing at auction and

then being bought by a German sexologist, who published it in Berlin in 1904 as

The 120 Days of Sodom, or the School of Libertinage. Publication made the

manuscript’s subsequent movements, if anything, still more mysterious. It has

since been stolen at least once, and been the subject of a great deal of

litigation. For decades it couldn’t travel outside Switzerland because of fears

it might be seized by the French authorities. Last year it sold at auction for

€7 million; Lloyd’s insured it for €12 million.

And this

was just the informal beginning of the celebrations commemorating the 200th

anniversary of Sade’s death. In October the manuscript, whose new owners are

seeking to have it declared a national treasure, was presented to the public in

a fifty-foot-long display case in Paris’s Institut des lettres et manuscrits as

part of an exhibition entitled Sade: Marquis de l’ombre, prince des Lumières

(the last word of the punning title might be translated as either ‘light’ or

‘enlightenment’). The Musée d’Orsay, too, mounted a lavish exhibition inspired

by Sade’s visions with a title – Attaquer le soleil – taken from The 120 Days.

It aimed to show, in the words of its organisers – one of whom was the writer

and Sade scholar Annie Le Brun – ‘themes of the ferocity and singularity of

desire ... of the bizarre and the monstrous’ in artists ranging from Goya to

Picasso, Ingres to Géricault, Cézanne to Rodin. In conjunction with the exhibition

the museum organised conferences, lectures, round tables and a film series

presenting adaptations of Sade’s works by Buñuel, von Stroheim, Pasolini, Guy

Debord, Peter Brook and Nagisa Oshima. Meanwhile, the Bibliothèque de la

Pléiade has published its fourth volume of Sade, a lavish 1150-page edition of

the great erotic writings: 120 Days of Sodom, Philosophy in the Bedroom and

Justine. The works span the decade between the end of one 13-year period of

confinement in 1790 and the beginning of a final 13-year period in 1801. The

hundreds of pages of critical and philological materials in the new volume

situate Sade in his violent and Enlightened times. They also bear witness to the

truly exceptional quantity of critical writing on him, from Beauvoir to

Foucault, to Blanchot, to Lacan, to Bataille, to Barthes, to Deleuze, to

Philippe Sollers.

These

national celebrations have been surprising for several reasons. Sade was jailed

by all three French governments under which he lived and each of his erotic

works was banned by the authorities on publication: an interdiction so serious

and durable that when a young publisher began issuing an edition of Sade in

1947 he was promptly arrested and only after more than a decade of appeals,

calling on expert testimony from Bataille, Breton, Cocteau and others, was

there an acquittal and a lifting of the ban. This radical reversal of official

esteem is, however, far less surprising than that such an about-face was

possible at all, given whom we’re talking about.

‘Now,

dear reader,’ we are told in The 120 Days, ‘you must prepare your heart and

your mind for the most impure story told since the beginning of the world.’ For

perhaps the first time in the history of the world such hyperbole is at risk of

being true. Four powerful members of the Ancien Régime – a judge, a bishop, a

banker and a duke – withdraw to a remote castle in the Black Forest, where they

are beyond the reach of all restraint. Everything protects them: the remoteness

of the location with its deep snow and impassable bridge, their wealth, their

influence, their ruthlessness. Extensive arrangements are made to link the four

of them together. To begin with, each of them has to marry – and debauch – the

daughter of one of the others. They then bind themselves further by signing a

contract stipulating that any member of the ‘quatriumvirat’ who misses a

session, shies away from a criminal act of any sort or degree, or goes to bed

in a state approaching sobriety during any one of the 120 nights planned is to

be fined ten thousand francs. A troop of 24 innocents, male and female, is next

recruited, as are four women who are masters in the art of libertine

storytelling. Every evening now begins with a story, which is followed by

performances of the acts it describes. (A curious feature of this much banned

book – as recently as 2012 South Korea banned a new translation – is that no

one ever commits a crime without first listening to a story designed to

encourage it. It’s almost as if the book were taunting the censors: all these

horrors, it keeps reminding us, were inspired by listening to licentious

stories.)

The 120

Days is a crescendo of crime. Over the course of four months four categories of

perversion – single, double, criminal and murderous – are both narrated and

practised. Each category contains 150 perversions. ‘Here is the story,’ we are

told, ‘of a great banquet where six hundred different dishes are offered to

you. Will you eat all of them? Of course not, but their prodigious number

extends the limits of your choice and, delighted by this increase of your

faculties, you will not think of chastising the Amphitryon who offers them to

you.’ This image becomes a good deal less appetising when we learn of some of

the things served – both literally (coprophagy is common) and metaphorically

(so is torture). The orgies that follow are complicated and often gymnastic.

Blasphemy proves a great source of inspiration. For example, a libertine ‘puts

a naked young woman astride a large crucifix; he fucks her in the vagina, from

behind, in such a way that the whore’s clitoris is stimulated by Christ’s

head.’ And just as there are physical gymnastics there are also mental ones.

When the time comes to break the incest taboo we learn of a ‘man who fucked the

three children he had had with his mother, from which resulted a daughter whom

he married to his son, so that in fucking her he was at once fucking sister,

daughter and daughter-in-law, and obliging his son at once to fuck sister and

mother-in-law’.

The

tortures are no less baroque, and far more disturbing. We learn of a woman who

is sewn inside the skin of a freshly killed ass so that, as the skin shrinks,

she is slowly suffocated. Another woman is placed on a special pivot and spun

to death. Hearts are removed, violated and replaced. The animal kingdom isn’t

spared either, as a libertine takes the emblematic bird of beauty, the swan,

places a Eucharist in its anus, sodomises it, and strangles it as he

ejaculates. The insatiable thirst for novelty leads one libertine to ‘place

himself in a specially constructed basket with a single opening, for his anus,

which is then coated with the sexual fluids of a mare, after which the basket

is covered in the skin of the animal. A stallion, specially trained for the

purpose, sodomises him while, inside his basket, he fucks a beautiful white

dog.’ (‘Sade,’ Breton wrote, ‘is a surrealist of sadism’).

It isn’t

all rape and torture, however. There is also philosophical discussion condoning

and encouraging rape, torture and more. As he was preparing to translate The

120 Days into English in 1938, Beckett wrote to a friend of his fear he might

be ‘banned & muzzled’ for his part in the project, as ‘the surface is of an

unheard of obscenity & not 1 in 100 will find literature in the pornography,

or beneath the pornography, let alone one of the capital works of the 18th

century, which it is for me.’

The

individual most responsible for this celebration of Sade is Guillaume

Apollinaire, who not only predicted that Sade would ‘dominate the 20th century’

but also deemed him ‘the freest spirit there has ever been’. A number of things

in Apollinaire’s encomium of Sade are debatable, though the same could be said

of the accounts of those from Balzac to Stendhal, Flaubert to Baudelaire,

Swinburne to Huysmans who had praised Sade before him. But Apollinaire was

unquestionably right about Sade’s spirit being preternaturally resistant to

intimidation. The first real report we have of the character of the young

marquis, born in Paris in 1740, concerns his interactions, at the age of four,

with the eight-year-old prince de Condé, who history suggests was something of

a bully: unsurprising given the fact that respect for the boy’s exceptionally

high rank prevented all but a very few individuals in France from reproving him

for anything (and given the fact that his tutor, the comte de Charolais, was by

all accounts a murderous psychopath). Sade was raised for a time alongside the

prince and although Sade’s illustrious family traced its origins to the 13th

century – and counted among its members the Laura for whom Petrarch invented

modern love poetry – there could be no question of parity. This was no

deterrent for the four-year-old Donatien, and when he was sent to stay in the

vast and beautiful Condé palace in the centre of Paris while his father was

away on diplomatic business, he trounced the boy twice his age, took away his toys

and so verbally dominated the young prince that whenever he entered the room

Sade would imperiously order him out.

Sade’s

father, much amused by his son’s ways, was a charming and well-liked courtier,

diplomat, libertine and man of letters. He saw to it that his spirited son had

an excellent education from private tutors in the vast libraries of the family’s

estates in Provence and at the celebrated Jesuit Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris.

While still a teenager Sade became a cavalry officer and, notwithstanding

Beauvoir’s speculation in ‘Must We Burn Sade?’ (1955) that he was bound to have

been a coward, he fought with distinction against the Prussians in the Seven

Years War. His superior officer’s laconic report reads: ‘Totally deranged, very

brave.’ Once back home Sade was married off to an intelligent and agreeable

woman whose family appealed to Sade’s father because they were wealthy and well

connected to the judiciary – a disastrous miscalculation. When accusations of

gross libertinage – blasphemy, whipping prostitutes and forcing them to whip

him, sodomy (a capital offence under the monarchy), liberal distribution of

high-grade chocolate laced with cantharides (also known as Spanish fly) – began

to circulate in Marseille, Versailles and Paris, Sade showed as little

restraint or respect as he had with the prince de Condé. He didn’t go to beg

clemency from the crown, as so many libertines of his day did after committing

far greater trespasses (such as murder). Nor did he apologise to his judicially

connected mother-in-law. Instead, he left Provence with his wife’s beautiful

younger sister (then resident in a Benedictine convent), whom he got to write a

letter which begins, ‘I swear to the Marquis de Sade, my lover, to give myself

to no other than him, to never marry, to remain faithfully bound to him so long

as the blood I use to seal this oath flows in my veins,’ followed by a

signature written in her own blood. When Sade was sentenced to death, in

absentia, for the crimes of poisoning and sodomy, with his life-sized effigy ceremoniously

carried to the main square in Aix-en-Provence, where it was then beheaded and

burned, the man himself was acquiring antiques in Italy with his sister-in-law

and to all appearances unperturbed.

For most

people imprisonment – the king of Sardinia soon put an end to Sade’s Italian

idyll – would quickly cure them of this sort of criminality. But not for Sade.

When, twenty years later, after more than one escape from prison, ‘Citizen

Louis Sade’ found himself president of the Section des Piques, one of the most

famous revolutionary sections, he pushed ahead with his radical programme of

de-Christianisation, knowing full well that this was prompting a fit of

murderous rage in the devout Robespierre (another member of the Section des Piques).

The Terror saw Sade sentenced (again) to death, a fate he was spared not by any

act of leniency, but because the bureaucracy had lost track of which prison he

was lodged in, and he happened to stay alive long enough for Robespierre to

find his own way to the guillotine. Free once again, Sade continued to do very

much as he pleased until he angered Napoleon Bonaparte and was returned behind

bars for the remainder of his life. There, he persuaded the warders that his

young mistress was his daughter (she wasn’t) and between her visits he put on

plays with casts of madmen and continued to write what he pleased.

The

book for which Sade is best known, the one Napoleon called ‘the most

abominable book which that most depraved imagination wrote’ and whose three

versions span the revolutionary decade covered in this Pléiade volume, is

Justine, or the Misfortunes of Virtue (1791). The first version of this tale of

two sisters – one who loves virtue, the other who loves vice – was written in

the Bastille; it was barely a hundred pages long, and contained no obscenity.

Phrases such as ‘the ensuing scene was as long as it was scandalous’ serve to

fire, or quench, the reader’s imagination at key junctures. But no such

restraint was employed in the succeeding versions as, by the end of the decade,

the work – now called The New Justine, or the Misfortunes of Virtue, followed

by the Story of Juliette, Her Sister (1799) – had grown to ten volumes covering

3700 pages. Sade’s claim on the book’s opening page that the story had been

‘softened as much as possible’ presents, in view of what follows, a frightening

sense of the possible.

At the

beginning of her story Justine is 12 (the same age as Lolita when hers begins).

She is blonde, beautiful, blue-eyed and improbably virtuous. Her older sister,

Juliette, has a very different moral make-up, one ‘sensitive only to the

pleasure of being free’. Juliette’s equally schematic beauty is dark, as is her

every design. Like Isabelle in Sade’s last work, The Secret History of Isabelle

of Bavaria, Queen of France, Juliette is made for the libertine world. No tie

but crime binds her, and none excites her more. When she encounters the man who

brought about her parents’ deaths, for instance, she exclaims: ‘Yes, fuck me,

Noirceuil! I love the idea of becoming the whore of my family’s executioner,

make me wet with semen rather than tears.’ Whether in the murderer’s bedroom,

in the convent of her youth, at the court of Catherine the Great, on the edge

of Vesuvius – everywhere, in fact, from Paris to Siberia – the same story is

told, and the same rules apply. We are introduced to commoners and kings, we

meet a man whose erect penis is so hard he can crack a walnut with it and a

giant who has ‘human furniture’. Thanks to her boundless love of vice, Juliette

finds all this thoroughly gratifying, and amasses great wealth and influence in

the process. Meanwhile, her little sister fares less well. Justine is made to

learn, in countless terrible ways, that no good deed goes unpunished. She is

raped and tortured with regularity.

Every

change Sade made in the successive versions was – morally speaking – for the

worse. After many years the sisters cross paths and compare notes. Justine is

penniless, battered, in rags, and under arrest for crimes she didn’t commit.

Juliette, countless crimes to her credit, is thriving. After freeing Justine

from the authorities, and delighting in the long tale of her woes, Juliette and

her libertine friends decide to turn her out in an advancing storm so as to

have Nature decide her fate. She is promptly struck by lightning which, in

defiance of fulminology, leaves her body not through her feet, but through her

vagina. (In earlier versions the lightning – acting in a fashion that was no

more physically possible but perhaps more seemly – left through her heart.) The

libertines rush to the scene of Nature’s crime, reflect on the lesson, and

praise Nature not only for confirming their beliefs but for sparing Justine’s

beautiful buttocks; there is then a last round of violations.

When

Sade was arrested at his printer’s in 1801 for the crime of having written this

book, he had with him extensive notes for still further amplification of the

story. This raises the question: do we really need to move our way through

every committable crime to understand that virtue brings only misfortune? Would

the beautifully written novella not have been enough?

In Literature and Evil (1957), Bataille wrote

that ‘nothing would be more pointless than to take Sade at his word, to take

him seriously.’ But how then are we to take him? The Goncourt brothers note

that Flaubert, while reading Sade, would merrily exclaim: ‘It’s the most

amusing stupidity I’ve ever encountered!’ In a more reverent vein Swinburne

spoke of ‘a thrill of the infinite in the accursed pages’. For many people in

the century Apollinaire predicted he would dominate, Sade’s supreme message was

the same violent one as the Revolution’s: freedom. Such a note of ecstatic

anarchy has been struck often, from The Surrealist Manifesto (1924) to Debord’s

Screams in Favour of Sade (1952), to the slogan that spread around the walls of

Paris during May 1968: ‘Sadists of all nations, popularise the struggle of the

divine Marquis!’ But this has not been the only note sounded. As news of Nazi

atrocities began to filter through to them in their Californian exile, Adorno

and Horkheimer dedicated the second chapter of their Dialectic of Enlightenment

(1944) to ‘Juliette, or Enlightenment and Morality’. In Sade they saw a dark

energy being released once Enlightenment rationality was freed from all

consensual restraints. The independence of mind which was the defining trait

and central credo of that rationality – Kant’s ‘Verstand ohne Leitung eines

anderen’, ‘understanding without the direction of another’ – was at the same

time the greatest threat to individual liberty. ‘The architectonic structure of

the Kantian system,’ they wrote, ‘like the gymnastic pyramids of the Sadean

orgy, announce an organisation of all aspects of life divorced from any

inherent goal.’ The Enlightenment which their dialectic sought to reveal, and

reorient, had as heritage not revolution, solipsism and anarchy but the

globalising society of surveillance and punishment in which the authors found

themselves living – and which seemed to be going up in flames.

These

were far from the last doubts voiced on this count. While reading Twenty Months

at Auschwitz by Pelagia Lewińska in 1945, Raymond Queneau noted that ‘the real

meaning’ of the camps was to ‘dehumanise human beings (which was the goal

proposed by Sade’s heroes)’, and found, in Sade, ‘a hallucinatory precursor of

the world ruled by the Gestapo’. Later that same year Queneau wrote that the

fact ‘that Sade was not personally a terrorist ... does not exempt those who

found themselves sharing to a greater or lesser extent the Marquis’s theses

from having to envisage, without hypocrisy, the reality of the concentration

camps’, where horrors were ‘no longer locked in the mind of a man, but carried

out by thousands of fanatics’. In The Origins of Totalitarianism Hannah Arendt

found that for an avant-garde of French intellectuals between the wars it was

‘not Darwin but the Marquis de Sade’ whom they read, and that ‘to them,

violence, power, cruelty, were the supreme capacities of men who had definitely

lost their place in the universe and were much too proud to long for a power

theory that would safely bring them back and reintegrate them into the world.’

Neither these commentators nor later ones such as Foucault – who was to remark

on ‘the unlimited right of an all-powerful monstrosity’ shared by Sade and the

Nazi death camps – suggest anything like inspiration. Which leaves open the

question of what it means to celebrate works that seem to have provided the

script for the most monstrous turns modern history has taken.

Understanding

Sade means understanding his libertines. Justine grew through ever more

attention being given to them, with each successive version casting more light

on what these supremely ruthless men and women are doing. What is made

immediately clear is that they are not hedonists, and are not simply following

their desires. Their pleasure principle is rigorous and reasoned, and their

ultimate goal isn’t even pleasure in any easily recognisable form. This is not

so much because it contains pain – it’s a common enough idea, from ancient

Greece to recent studies in neuroscience, that pain and pleasure are wedded in

mysterious ways – but because their goal is to feel nothing at all, precisely

as they perform the most criminal acts imaginable. Sade’s libertines cede to

every criminal, harmful, violent impulse that occurs to them; they find that

reason not only encourages but obliges them to do so. But the same does not