Friday

marked the bicentary of the great radical writer who wanted culture to spark

the imaginations of ‘ordinary’ people

“Shall

rank corruption pass unheeded by,

Shall

flattery’s voice ascend the wearied sky;

And

shall no patriot tear the veil away

Which

hides these vices from the face of day?

Is

public virtue dead? – is courage gone?”

No, not

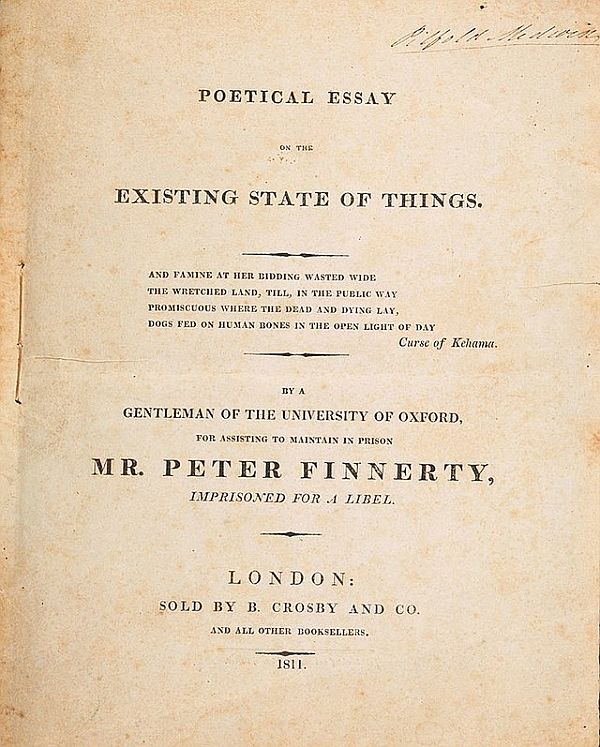

a description of the moral void of contemporary Britain, but lines from

Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things, an excoriation of the moral

devastation wreaked in late Georgian Britain two centuries ago. It was written

by Percy Bysshe Shelley and published anonymously in 1811, in support of the

radical Irish journalist Peter Finnerty, who had been imprisoned for seditious

libel after accusing the Anglo-Irish politician Viscount Castlereagh of the

torture and executions of Irish rebels challenging British rule.

Shelley’s

poem was “lost” for nearly 200 years, before a single copy of the pamphlet was

“rediscovered” in 2006, and a decade later bought by Oxford’s Bodleian Library,

so finally it could be read by the public again. A poem that speaks to our age

as much as it did to the Britain of two centuries ago.

Friday

marked the bicentenary of his death. He was drowned after his boat, carrying

him home after visiting his friend and fellow poet Lord Byron in the Italian

town of Livorno, capsized in a storm. He was a month short of his 30th

birthday.

Wordsworth

said of Shelley that he was “one of the best artists of us all; I mean in

workmanship of style”. He is also one of our most significant political

essayists, “the relentless enemy of all irresponsible authority, especially the

irresponsible authority which derives from wealth and exploitation”, as Paul

Foot, whose 1981 work Red Shelley helped restore the significance of Shelley’s

political work, observed.

Shelley’s

greatest gift was in the deftness with which he interwove the poetical and the

political. Poetry had, for Shelley, of necessity to appropriate a political

dimension. And politics required a poetical imagination. That was why, as

Shelley put it in a celebrated line from his essay A Defence of Poetry, “poets

are the unacknowledged legislators of the world”.

Poetry

did not stand aloof from the world but sought to engage with it and to

transform it. We live in an age in which working-class politicians can be

mocked for attending the opera. For Shelley, the measure of high culture lay in

the degree to which it could spark the imaginations of ordinary people.

Born

into landed aristocracy, educated at Eton and Oxford, Shelley seemed destined

for a life at the heart of the British establishment. However, he was also born

into an age of tumult, a maelstrom, both intellectual and political, unleashed

by the French Revolution.That tumult helped Shelley find his voice. And

Shelley, in turn, tried to give voice to it. He was, as his most insightful

biographer Richard Holmes put it, like his poetry, not ethereal as literary

tradition would have it, but “darker and more earthly”.

Shelley’s

first significant work – The Necessity of Atheism – published in his first year

at Oxford, led to his expulsion from the university and strained his

relationship with his father to breaking point. Living precariously as an

itinerant writer, Shelley found his home instead on the radical edge of British

politics, a crusader against moral and political corruption, a campaigner for

republicanism and parliamentary reform, for equal rights and the abolition of

slavery, for free speech and a free press, for Irish freedom and Catholic

emancipation, for freedom of religion and freedom from religion.

His

political ideals were often contradictory, his revolutionary spirit clashing

with his Fabian instincts for gradual, non-violent change. Yet, unlike fellow

Romantic poets, such as Wordsworth and Coleridge, Shelley never abandoned his

radicalism, his disdain of authority or his celebration of the voices of

working people.

His

personal life was tumultuous, too. He left his first wife, Harriet Westbrook,

who later took her own life, to live with, and eventually marry, Mary Godwin,

daughter of radical philosophers Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. He was

forever trying to find refuge from debt collectors and eventually he and Mary

left Britain to live in Italy. Mary Shelley would create, in Frankenstein, one

of the great explorations of the contradictions of modernity and of what it was

to be human.

Despised

by the literary and political establishments, Shelley wrote for the

working-class autodidacts for whom learning and culture were means both of

elevating themselves and of challenging those in power. Fearful of the

consequences, his work was suppressed by the authorities, either through direct

censorship or through threatening publishers with the charge of sedition.

As a

result, much of Shelley’s work was published only after his death. The Masque

of Anarchy is perhaps the most famous political poem in the English language,

written in furious anger after the Peterloo massacre of 1819, when at least 15

people were killed as cavalry charged into a crowd of around 60,000 who had

gathered to demand parliamentary reform and an extension of suffrage. Shelley

sent it to his friend, the radical editor and publisher Leigh Hunt. But Hunt

did not publish it, for to do so would have been to invite immediate

imprisonment for sedition. Not until 1832 was the poem, with its celebrated

last stanza, finally published:

“Rise

like Lions after slumber

In

unvanquishable number –

Shake

your chains to earth like dew

Which in

sleep had fallen on you –

Ye are

many – they are few.”

In the

decades that followed Shelley’s death, his poetry became an inspiration across

generations and borders. Queen Mab became known as the Chartists’ Bible, read

aloud at working-class meetings. The Suffragettes’ slogan, “Deeds, not words”,

is taken from The Masque of Anarchy. And that final stanza has been on the lips

of many who have “shaken their chains”, from striking Jewish garment workers in

early 20th-century New York to protesters 80 years later in Tiananmen Square and

a century later in Tahrir Square.

And most

of all, perhaps, it is in his insistence that we question the claim to power of

those in authority that we most need Shelley’s voice today. For, as he put it

in Queen Mab:

“Nature

rejects the monarch, not the man;

The

subject, not the citizen…

… and

obedience,

Bane of

all genius, virtue, freedom, truth,

Makes

slaves of men, and of the human frame

A

mechanized automaton.”

Long

gone, but speaking clearly to our age – Shelley, the poet of moral and

political corruption. By Kenan Malik.

The Guardian, July 10, 2022.

It is 200

years since the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley drowned at sea at the age of 29. At

the time, his life and works were considered scandalous, due in part to his

reputation as a sexually liberated, vegetarian atheist, living in a reported

ménage à trois. He did not achieve literary fame during his lifetime, but today

he is one of the most celebrated British poets.

Shelley

was writing during what is now called the Romantic period, which lasted from

around 1780 to 1840. This was a time of innovative thinking and new ideas which

took place in science, industry, the arts, and particularly in literature.

Other Romantic writers include William Wordsworth, Jane Austen, Maria

Edgeworth, and Shelley’s friend, Lord Byron.

Shelley’s

notoriety began when he was publicly expelled from Oxford University for

publishing an atheist pamphlet. Four years later, he courted scandal again,

when he abandoned his pregnant wife and eloped with the 16-year-old Mary

Wollstonecraft Godwin (later the famous author of Frankenstein) along with her

stepsister, Claire Clairmont. His poetry reflected his personal notoriety. In

particular, the poem Laon and Cythna was criticised due to its attacks on

religion and descriptions of a brother-sister incestuous relationship.

Together

with Mary and Claire, Shelley lived a nomadic existence, moving around the UK

and across Europe, before settling in Italy. It is here that Shelley wrote some

of his best-loved poems, including Adonais and began his final, unfinished

poem, The Triumph of Life. It is also where Shelley died. His sailing boat, the

Don Juan, sank near the Gulf of Spezia. All three passengers drowned and washed

ashore days later.

Angel in

death

The

response to Shelley’s death was phenomenal. A leading Tory newspaper, the

Courier, ran an obituary which read: “Shelley, the writer of some infidel

poetry, has been drowned: now he knows whether there is a God or no.” His death

became a Romantic myth that steadily grew and his poetry became increasingly

popular. His wife, Mary, began this Shelleyan legacy, describing him as an

“angel”, a description that endured throughout the 19th century.

By 1889,

the continued fascination around Shelley’s death meant that his cremation

became the subject of a painting; Louis Édouard Fournier’s The Funeral of

Shelley. The painting depicts a remarkably preserved corpse on a pyre,

surrounded by his friends, including Lord Byron (who in reality went swimming

in the sea during his funeral) and Mary Shelley kneeling in the background (she

did not attend the funeral at all).

Shelley’s

heart famously did not burn and was given to Mary. Modern physicians believe it

may have calcified due to a bout of tuberculosis. Reportedly, it was found

wrapped in a sheet of Shelley’s poetry after Mary’s own death in 1851 and was

buried in Bournemouth alongside her.

During

the Victorian period, Shelley became an inspiration to fellow literary figures,

including Robert Browning, George Eliot, Edgar Allan Poe, and Alfred, Lord

Tennyson. Shelley’s reputation was sanitised to such an extent that even his

old college in Oxford forgave his rebellious past and installed a monument

dedicated to him in 1893. Sculpted by Edward Onslow Ford, a graceful, angelic

Shelley lies on a sacrificial altar, guarded by a weeping woman.

Shelley’s

Romantic reputation today

Interest

in Shelley waned in the early 1900s and it wasn’t until the latter half of the

century that his writings became respected due to the varied and many far

reaching concerns found within them. His complex and fascinating personal life

has also been the subject of a number of biographies and a source of endless

fascination.

Perhaps

his biggest claim to fame today is his marriage to the “mother” of science

fiction, Mary Shelley. It is known that Shelley assisted his wife with her

Frankenstein manuscript and the two had a collaborative literary relationship.

This work, alongside the recently popular The Last Man, are certainly wider read

than Shelley’s poetry, which are often limited to educational settings.

In

popular culture, it is mainly through Shelley’s relationship to Mary and other

Romantic figures that he is remembered. The 2017 film, Mary Shelley, starred

Douglas Booth as the poet. As the title suggests, Shelley’s role is depicted as

secondary to that of his wife, whose life is the centre of the story. Doctor

Who, the most popular science fiction show in the UK, included Percy and Mary

in their 2020 episode The Haunting of Villa Diodati. Again, the focus was

placed on the genesis of Frankenstein. Even the popular comedy series Drunk

History’s 2016 segment on Shelley identified his relationships with his wife

and friend, Lord Byron, as central to his appeal.

But the

200th anniversary of Shelley’s death is am important literary bicentennial.

International events have been happening over the past year to mark key moments

in his life, including #Shelley200. Exhibitions, including at Horsham Museum

and the Shelley Conference in London, taking place this weekend, demonstrate

the lasting appeal and ongoing interest in his works. For many, Shelley’s

legacy lives on.

Ozymandias

or To A Skylark are a great introduction to Shelley’s poems if you want to read

his works.

Percy

Bysshe Shelley at 200 – how the poet became famous after his death. By Amy

Wilcockson.

The Conversation, July 8, 2022.

Percy

Bysshe Shelley: poet, atheist, and determined opponent of the over-powerful.

What would he have made of the dramatic resignation this week by Boris Johnson

after weeks of his authority ebbing away? A flight of fancy of course, but an

irresistible one for me, whose working life these last days and weeks has been

dominated by the disintegration of Johnson’s credibility. All the while I’ve

been preparing – in my downtime – to commemorate 200 years since the death of a

titan of English poetry and a political radical.

Like the

outgoing prime minister, Shelley went to Eton, but the common ground stops

there. He was a rebel at heart, distrustful of authority, and raged at abuses

of power by what he saw as the unaccountable and heartless establishment.

Perhaps his most famous poem, Ozymandias, mocks the empty legacy of a puffed-up

despot. Meanwhile England in 1819, written in the last year of the reign of

George III who had for years been mentally incapable, tells of “Rulers who

neither see nor feel nor know, But leechlike to their fainting Country cling”.

The Mask

of Anarchy satirises the government of the day as the epitome of anarchy and

injustice, and ends with an impassioned appeal for ordinary people to rise up:

“Ye are many, they are few.” Shelley was thrown out of Oxford in connection

with his essay The Necessity of Atheism, and he strongly believed in poetry as

a powerful force for political good. “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators

of the world,” he wrote. For Shelley, the poetic was political.

Part of

Shelley’s allure is the people who surrounded him. His wife was Mary Shelley,

daughter of another political radical, William Godwin, and Mary Wollstonecraft,

generally recognised as the mother of British feminism. At the age of 18, Mary

wrote Frankenstein, an astonishingly mature work about the hubris of an

irresponsible inventor who creates the first of a new race but denies its human

needs – with catastrophic consequences. At this time, Percy and Mary were

living and travelling with Lord Byron and Mary’s half-sister Claire Clairmont,

a formidable ménage of literary creativity.

Shelley’s

politics were progressive, as were his political attitudes towards women. He

was an ardent supporter of female emancipation and of gender equality, and had

a profound respect for the work of Mary Wollstonecraft. His personal relations

with women were less respectful. Shelley abandoned his 19-year-old wife,

Harriet Westbrook, and their two children in 1814 to elope with the 16-year-old

Mary. Two years later Harriet drowned herself in the Serpentine in London. In

the two years before he died – a dark and difficult time when Mary endured

repeated miscarriages and the death of their small son – he wrote tender poems

about Jane Williams, the wife of his friend Edward. Whether this infatuation

would have led anywhere will remain unknown; Shelley and Edward both drowned

off the coast of Liguria in north-west Italy on 8 July 1822 after a violent

squall hit their small boat. Shelley’s body was identifiable only by the

collection of Keats poems found in his jacket pocket.

They all

died young, these second-generation Romantic poets – Shelley at 29, Keats at

25, Lord Byron at 36. As I was growing up, it was Keats’ work that was the most

compelling – a yearning and eager poetry that had a youthfulness about it, much

of it focused on the process of desire, and with an aesthetic wish to capture

and fix desire through art. But Shelley fascinates through his complexity – his

reformist zeal is matched by a strong sense of personal gloom and pessimism,

which he works through in his poetry, using nature as a counterpoint to his

human suffering. If Keats was a first love, Shelley is a mature one.

A few

weeks ago, a group of us went on a visit to the Italian resort of Lerici, where

Percy and Mary had their last home in the Casa Magni before his untimely death.

Shelley was haunted by visions of himself – a doppelganger he saw from the

balcony of the Casa Magni – and in a park next to the house we listened to

readings of his poetry by, among others, the poet laureate Simon Armitage, and

imagined him there. In a few weeks’ time, we will go to the non-Catholic

cemetery in Rome, where Shelley and Keats are buried, to commemorate him once

again.

Ozymandias,

“king of kings”, left no legacy whatsoever; the opposite is true of the man who

created him.

‘For

him, the poetic was political’: how Shelley stands tall as a great Romantic

poet. By Reeta Chakrabarti. The Guardian. July 8, 2022.

Nothing

in his life became him like the leaving of it. Percy Bysshe Shelley, clothed in

black, lies on the branches of the funeral pyre; his pale face might be

sleeping, his hair is swept back, his hand has fallen to his side. He still has

on his leather shoes. Like the “blithe spirit” in “To a Skylark”, he is ready

to transcend his physical form. Smoke billows across the barren wastes of

Viareggio, Italy, the sky is autumnal and overcast and the sea in which he drowned is a

blade of silver on the horizon. To the left we see a watch tower, a waiting

carriage, a bare and solitary tree and, in the foreground, three Heathcliffian

figures: Lord Byron, his necktie blowing raffishly in the wind, Byron’s

“bulldog” Edward John Trelawny, and the poet and journalist Leigh Hunt,

clutching a white handkerchief. Behind them the poet’s widow, Mary Shelley, kneels in prayer. The scene might be a mockery of the central tableau

in her novel Frankenstein, where the creature the scientist has pieced together

is stretched along the bench, waiting to be jolted into life.

Shelley

did a great deal to mythologise himself, but the public’s myth of Shelley,

which began with his funeral, and Louis Édouard Fournier’s 1889 painting –

copies of which, said WB Yeats, hung on the wall of every art class – bears

little relation to the reality of the event. When Byron died fighting for Greek

independence in 1824, England collapsed into the kind of mourning we would not see again until the

death of Diana, Princess of Wales, but Shelley’s death aged 29 in July 1822,

like that of Keats in 1821, was not at first regarded as a national tragedy.

Before he was sanctified Shelley was dismissed – if he was spoken of at all –

as an atheistic, anti-establishment, vegetarian anarchist who believed that a

poem was a radical instrument. “Shelley, the writer of some infidel poetry, has

been drowned,” reported The Courier when the news reached England. “Now he

knows whether there is a God or not.”

Setting

sail from Livorno on 8 July, Shelley’s sailing boat got caught in a squall off

the Bay of Spezia. When he washed ashore on 18 July his hands and face had been

eaten by dogfish; he was identified by the edition of Keats in his pocket. The

decomposing body was buried in the sand before being dug up for the cremation,

which took place on 16 August. Rather than being a blustery day, the combined

heat of the sun and the fire, wrote Trelawny in his Recollections of the Last

Days of Shelley and Byron, “was so intense that the atmosphere was tremulous

and wavy”.

Trelawny,

who was prone to exaggerate, described how the corpse, doused in more wine than

Shelley had consumed in his lifetime, “fell open and the heart was laid bare.

The frontal bone of the skull… fell off; and as the back of the head rested on

the red-hot bottom bars of the furnace, the brains literally seethed, bubbled

and boiled as if in a cauldron, for a very long time.” “Is this a human body?”

Byron apparently declaimed. “Why, it’s more like the carcass of a sheep.” Women

were excluded from funerals and so Mary Shelley stayed at home while Hunt, the

last person to see his friend alive, was too distraught to leave the carriage.

So it was only Byron and Trelawny who watched Shelley burn. When it was over,

Byron went for a swim and Trelawny grabbed the heart from the flames and passed

it on to Hunt, who reluctantly gave it to Mary. She kept it on her writing desk

for the rest of her life.

It suits

Shelley’s self-image to see him as a lonely sailor in a storm, but he was not

alone when his boat went down; he was accompanied by his friend Edward

Williams, whose own body was cremated the day before. The two men had been to

visit Hunt who had just arrived in Italy with the aim of starting a journal

called The Liberal. Williams and his common-law wife Jane had been living with

the Shelleys in a former boathouse called Casa Magni in Lerici, where the sea

came up to the front door.

The

previous month Mary, having already buried three of her four children, nearly

bled to death during a miscarriage. “No words can tell you how I hated our

house & the country about it,” she recalled of that time. Casa Magni had

become a personality to be feared and Shelley, addicted to laudanum and

infatuated with Jane Williams, had started to hallucinate. In one vision he saw

a naked child rising from the water, his hands clasped in joy. “There it is

again!” he told Edward Williams, pointing to the sea. “There!” In another

vision he saw Jane and Edward covered in blood, and in another a man with his

own face was strangling Mary. He would be happiest, Shelley told a friend, if

the past and future could be obliterated and he, Jane and her guitar could

simply float away in a boat.

During

Shelley’s lifetime, it was Byron – flash, cynical, and satirical – who was in

the ascendance. The Corsair – dashed off, Byron bragged, between dinners – sold

10,000 copies on the day it was published, while Shelley’s print-runs never

exceeded 250. The transformation from infidel poet to “ineffectual angel” (the

term is Matthew Arnold’s) began with the publication of Leigh Hunt’s Lord Byron

and Some of his Contemporaries (1828) and Trelawny’s Recollections of the Last

Days of Shelley and Byron (1858). Hunt, the first critic to recognise the

genius of Shelley and Keats, reminded the reader that not only was Shelley “a

baronet’s son” with the taste and manners of his rank, he was also too fine for

this world.

By the

1860s Walter Bagehot would describe Byron’s verse as “a metrical species of the

sensation novel” and Shelley’s “as a serious and deep thing”. If Byron was a

melancholy dandy, Shelley was an instrument of spontaneity. “Make me thy lyre,

even as the forest is,” Shelley wrote in “Ode to the West Wind”. A self-playing

instrument, the lyre (whence “lyric”) is the quintessential metaphor for

Romantic inspiration, and “for the poet to yield himself to and be borrowed by

the wind”, as Merle Rubin puts it, “is almost the Shelleyan stance”. So when

Will Ladislaw (the idealist modelled on Shelley) explained in George Eliot’s

Middlemarch (1871) that a poet was a recipient of external and internal

impressions, he was singing from Shelley’s songbook:

To be a poet is to have a soul so quick to

discern, that no shade of quality escapes it, and so quick to feel, that

discernment is but a hand playing with a finely ordered variety on the chords

of emotion – a soul in which knowledge passes instantly into feeling, and

feeling flashes back as a new organ of knowledge.

In 1891

Shelley was fictionalised again as Angel Clare in Hardy’s Tess of the

D’Urbervilles, and in 1893 Edward Onslow Ford’s lavish marble reclining

sculpture The Drowned Man was put on display in University College, Oxford, the

alma mater from which the poet had been expelled 80 years earlier for

publishing a pamphlet called The Necessity of Atheism.

What

would have happened to Shelley’s reputation had he died an old man in Surrey

rather than a young man in the Tyrrhenian sea? If dying young was proof of

sensibility, doing so in the Mediterranean was a guarantee of deification. Was

Shelley’s best work behind him in 1822? Now recognised as the heir to Dante and

Milton, Shelley gave us some of the loveliest lyrical poems in the language

(“To a Skylark”, “Ode to the West Wind”, “Ozymandias”); “Adonais”, the elegy to

Keats read by Mick Jagger in the concert at Hyde Park after the death of Brian

Jones; the dramas, “The Cenci” and “Prometheus Unbound”; the conversational

poem “Julian and Maddalo” and the sublime “Epipsychidion”. But it is “The

Masque of Anarchy”, written in the aftermath of the Peterloo Massacre in August

1819 when cavalry charged at campaigners for parliamentary reform in

Manchester’s St Peter’s Field, for which he is best remembered.

Paul

Foot, whose book Red Shelley (1981) turned the poet from a representative of

the Romantic imagination to a mascot of the left, could recite the whole of

“The Masque of Anarchy”, as could his uncle, Michael Foot, and his three sons.

Jeremy Corbyn did recite it – or at least its final stanza – in front of a

crowd of 120,000 at Glastonbury Festival in 2017:

Rise like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number –

Shake

your chains to earth like dew

Which in

sleep had fallen on you –

Ye are

many – they are few.

The same

lines were chanted in Tiananmen Square in 1989, in Tahrir Square during the

Egyptian revolution in 2011, and at the Poll Tax marches; “The Masque of

Anarchy” is not only the greatest protest poem in English but in any

language.

What would

have happened to Mary Shelley had her husband been around for the next 50

years? She had more peace as a widow than as a wife. “We have now lived five

years together,” she wrote in 1819, “and if all the events of the five years

were blotted out, I might be happy.” Before Shelley fell in love with Jane

Williams there had been Sophia Stacy, and before that there was Emilia Viviani,

and Mary’s step-sister Claire Clairmont. Shelley’s first wife, Harriet, was 15

when she met him, 16 when she married him, 18, and pregnant with her second

child, when he abandoned her for Mary, and 21 when, pregnant with her third

child, she drowned herself in the Serpentine in December 1816. Two months

earlier, Mary’s half-sister, Fanny Imlay, also in love with Shelley, had swallowed

a fatal dose of laudanum. Loving Shelley was lethal because Shelley idealised

love. The notes to “Queen Mab” outlined his philosophy: “Love withers under

constraint… Love is free: to promise for ever to love the same woman, is not

less absurd than to promise to believe the same creed.”

Shelley

learned his doctrine of free-love from the radical philosophy of Mary’s

parents, William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. Godwin’s anti-marriage,

anti-ownership treatise, the Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, paved the

way for the Romantic experiment in communal living, and Mary Wollstonecraft,

who had died giving birth to Mary Godwin, took on for her daughter and her

generation a legendary status. When Shelley and the 16-year-old scion of these

two extraordinary figures ran away together in 1814, they assumed they would

win Godwin’s approval; he had, after all, raised his daughter to be “a

philosopher” and “a cynic”. But in the time-worn fashion of fathers, Godwin was

appalled by what he saw as the poet’s seduction of his daughter. It was not

Shelley, however, who had seduced Mary, but Godwin who had seduced Shelley.

Poor Harriet Shelley realised this straight away: “The very great evil that

book has done is not to be told,” she said of Political Justice. Meanwhile,

Harriet saw that Mary had “heated [Shelley’s] imagination by talking of her

mother [and] going to the grave with him every day”. Despite being disowned by

Godwin, Mary and Shelley scoured the pages of his writing for guidance on how

to lead their future lives, which were to be spent in voluntary exile in Italy

with no home, no income, no certainty.

Two

hundred years after his death, Shelley is no longer stigmatised, mythologised,

or even, beyond being chanted at protests, much read or understood. He was a

revolutionary poet, but his sense of revolution involved an expansion of the

concept of love which came from deep inward reflection. “We want,” he

explained, “the creative faculty to imagine that which we know; we want the

generous impulse to act that which we imagine; we want the poetry of life.”

Perhaps

he will be cancelled and disappear from the university curriculum, and future

generations will not hear what Shelley had to tell us about tyranny and freedom

and how best to live. Or perhaps he will be read again, closely and carefully,

in his full complexity. Shelley was “emphatically”, as William Rossetti put it,

“the poet of the future” and it is to Shelley’s sonnet, “England in 1819”, that

we might turn when we consider the “old, mad, blind, despised and dying”

Vladimir Putin:

Rulers

who neither see nor feel nor know,

But

leechlike to their fainting country cling

Till

they drop, blind in blood, without a blow.

The last

days of Percy Bysshe Shelley : It was 200

years ago that Shelley drowned, aged 29 – but his poems of tyranny and

freedom speak to our own darkening age. By

Frances Wilson. The New Statesman, July 6, 2022.

No comments:

Post a Comment