Growing

up in Britain means encountering a certain kind of early 19th-century culture

as a given. Address book, china mug or wall calendar, the decoration is sure to

be that overloaded harvest wagon, The Hay Wain (1821), painted by John

Constable. Elsewhere, riffing comedians and headline writers crank out pun

after pun on the first line of William Wordsworth’s lyric poem, ‘I Wandered

Lonely as a Cloud’ (1804).

I

vividly remember the teenaged sense of cultural claustrophobia that can result.

These clichés were what we believed Romanticism to be, and they represented a

past whose continuity we wanted to break. They belonged among the knitted

teapot covers and potpourri sachets on the side tables of other generations’

lives. High school had taught us roughly when Romanticism was: from 1770, when

Ludwig van Beethoven, G W F Hegel and Friedrich Hölderlin were born, to 1850,

by which time Honoré de Balzac, Frédéric Chopin, Edgar Allan Poe and Mary

Shelley had died. But the curriculum made zero connection between the artefacts

it called ‘Romanticism’ and the realpolitik and real-life battles of Napoleonic

imperialism, the Italian Risorgimento, the nation-building that culminated in

1848’s Year of Revolutions across Europe and Latin America, or the gradual

abolition of slavery. Nor did we have any clue that Romanticism spoke directly

to debates that raged – and still rage – around our own lives, whether about

the violent resurgence of nationalism, or about identities and their associated

rights.

So of

course we had no sense of affinity with the radicalism and feelingful

impatience of those youthful iconoclasts, the Romantic protagonists themselves.

Their precocity passed us by: Felix Mendelssohn composing masterpieces as a

teenager – the Octet Op 20 at age 16, A Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture Op 21

at 17 – or Mary Shelley writing her second book, Frankenstein, when she was 19.

Admittedly, that great trio of second-generation poets – John Keats, Percy

Bysshe Shelley and Gordon, Lord Byron, all dead by 36 – would probably have

seemed old to us. (Mick Jagger may have read from Shelley’s Adonais at the

start of the Rolling Stones’ 1969 Hyde Park gig: but for my generation, this

too was antediluvian.)

And yet

a belief – not always fully rationalised – in the value of the direct and

unfettered underlay the movement, and could serve as a rallying call to a new

generation. Romanticism itself eschewed conventional pieties, from marriage to

the monarchy, in favour of immediate, intuitive thought; second-hand

scholarship for risk-all radicalism. Freshness of thought was the ‘blithe

Spirit’ with ‘unpremeditated art’, the ‘Wild Spirit, which art moving

everywhere; / Destroyer and preserver’ of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘To a Skylark’

and his ‘Ode to the West Wind’, written in June 1820 and October 1819

respectively.

How

could such vibrancy have been reduced, within two centuries, to a genteel

wallpaper for life in the global North?

One

answer must be commodification, with its diminishing circle of repetition. It’s

an irony that arguably the most radical movement in European thought should

have been appropriated by the conservative forces of the market, but it’s also

predictable. Among the market’s instincts is to monetise proven success,

(literally) capitalising on already prepared appetites and cutting the costs of

risk. And Romanticism has been, put simply, a global success: ‘let me count the

ways,’ as that late Romantic, the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning, puts it, in

Sonnets from the Portuguese #43. (Itself another of those Romantic fragments to

have attained the cultural reach of cliché.)

Romanticism

was the engine of the French revolution, of the more-or-less pro-democratic

revolutions of 1848, and of the successive formation of nation-states that

continued for another century to ripple across Europe to the borders of Russia

– and across every other continent where Romantic ideas about selfhood and

self-determination forced the retraction of European imperialism: as far as

Africa, Asia and the Indian subcontinent. Romanticism was the starting point of

experimental science. Much of today’s world – its cities and its countrysides –

are shaped by the agricultural and industrial revolutions that science informed.

The

German philosophers who were the movement’s patron saints, among them Hegel and

Immanuel Kant, shifted the terms of Western engagement with the world and its

understanding of the nature of experience. Artists and writers developed genres

of expressive realism – from the Bildungsroman to confessional verse – that are

still in mainstream use today, far beyond Romanticism’s European cradle. Above

all, in its regicidal turn from divinely ordained jurisdiction to authority

earned by the exercise of reason, Romanticism placed the human individual at

the centre of its universe. That human individual – not yet either a citizen or

a subject but an actor defined by their thoughts and actions – contained the

seeds of that other world actor without a hinterland, the 21st-century

consumer.

This

global reach is exceptional. On the other hand, it outreaches what we might

call brand recognition. While the movement itself embraced radical political,

cultural and intellectual transformation, brand Romanticism has been reduced to

products appropriated by a culture of nostalgia, reiteration and risk-less

familiarity. Tablemats reproduce landscapes by Constable and his great

contemporary, J M W Turner. Biopics retell the love lives and tragic deaths of

Keats and Lord Byron. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and his creature schlock

their way across popular culture, from graphic novel to comic movie turn. While

– and because – these have become cultural clichés, the revolutionary force of

the ideas underlying them has dropped away.

For

example, the affinities between Frankenstein’s naked creature, that literal

sans-culotte, and the peasantry whom the French Revolution was originally

intended to rescue from abjection have been forgotten, along with their

author’s early formation by her parents’ pro-Revolutionary philosophies. Yet

how audible it is:

“I felt

cold also, and half frightened, as it were, instinctively, finding myself so

desolate. Before I had quitted your apartment, on a sensation of cold, I had

covered myself with some clothes, but these were insufficient to secure me from

the dews of night. I was a poor, helpless, miserable wretch …””

A

generation earlier, the ‘roofless Hut; four naked walls / That stared upon each

other’ in Wordsworth’s ‘The Ruined Cottage’ (1797), the poem that eventually

became Book I of The Excursion (1814), is not Gothic picturesque, but a metonym

for the failed lives of the desperately poor. Constable painted underpopulated

landscapes not for aesthetic reasons but because the people who had lived there

until recently had been cleared away by the nation’s landowners. The infamous

emigrations that resulted from the era’s Scottish Highland Clearances and that

genocide by starvation, the Irish Potato Famine, were echoed in smaller scale

across Britain.

Still,

there’s nothing to indicate to the Sunday afternoon visitor, browsing the gift

shop at the exit of some English mansion, that its reproduction telescopes, or

glossy postcards of the parkland folly, are traces of violent social, political

and intellectual rupture: let alone of a period of historical shame. On the

contrary, they seem comfortingly to suggest a robustly established culture –

the one in which Jane Austen’s ever-popular novels, for example, are set.

These

comedies of manners acknowledge, and so illustrate for us today, the influence

Romantic thought was having on Austen’s contemporaries. Both her first

published novel Sense and Sensibility (1811) and the posthumous Northanger

Abbey (1817) – whose title alone signals gleeful Gothic pastiche – mock the

effects of Romantic ideas about love and emotion, or ‘sensibility’, on young

women in a marriage market that traded sexual charm for financial security. But

in Austen’s world Romanticism is a mere fashion, which will be long outlasted by

the economic self-protection and dynastic marriages that characterise what Noël

Coward could still, a century later, call ‘The Stately Homes of England’. (As

the economist Thomas Piketty has pointed out, Austen introduces her male

characters by their incomes, so defining – and fixed – are they.)

Of

course, Coward’s song, from his show Operette (1938), is waspish camp, as when

he trills:

The

Stately Homes of England,

How

beautiful they stand,

To prove

the upper classes

Have

still the upper hand

we

should not only note the sting in that last line, but hear behind it the 1827

original by the Romantic-era poet Felicia Hemans:

The

stately Homes of England,

How

beautiful they stand!

Amidst

their tall ancestral trees,

O’er all

the pleasant land.

When

Hemans published ‘The Homes of England’, in the widely read and influential

Blackwood’s Magazine, she gave it an epigraph from Sir Walter Scott’s Marmion:

A Tale of Flodden Field (1808): ‘Where’s the coward that would not dare / To

fight for such a land?’ (A grace-note: Scott’s verse-novel formed part of the

Celticism that made him famous across Europe.)

The

thrust of Hemans’s poem – there’s something special about ‘British values’ that

is worth fighting for – is familiar in today’s post-Brexit archipelago, where

an unpopular British prime minister can expect to seduce the electorate by

reintroducing pre-metric measurements, the aptly named imperial system. In her

essay ‘American Originality’ (2001), the US Nobel Laureate Louise Glück calls

this:

“the language of appeal that links Churchill

to Henry V, a language that suggests the Englishman need only manifest the

virtues of his tradition to prevail. These appeals were particularly powerful

in times of war, the occasion on which the usually excluded lower classes were

invited to participate in traditions founded on their exclusion.”

Hemans’s

poem had already embraced this doublethink. She brackets the idea that England

is ‘free’ and ‘fair’ with its polarisation of wealth – ‘hut and hall’ is the

tidy alliteration she comes up with – as if, far from a contradiction, this

were the correct order of things:

The

free, fair Homes of England!

Long,

long, in hut and hall,

May

hearts of native proof be rear’d

To guard

each hallow’d wall!

In other

words, like Austen (1775-1817), Hemans (1793-1835) was more Romantic-era than

Romantic. That distinction is conveniently missable today, when her florid

language sounds of a piece with the decorative role to which the movement is

relegated. Hemans had been born late enough to benefit from the radical ideas

about education and gender roles that Mary Wollstonecraft expounded in Thoughts

on the Education of Daughters (1787) and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

(1792).

This

complex, metamorphosing and unstable social world was very different from the

fictional givens of Austen’s social round. Wider questions about society were

being pressingly posed by the French Revolution, just 20 miles away across the

English Channel; and by the work of political philosophers such as Wollstonecraft’s

soon-to-be husband William Godwin, whose An Enquiry Concerning Political

Justice, published in the year Hemans was born, advocated direct action against

traditional structures of Church and state, including the repudiation of

marriage. Such changeable social relations perhaps made it easier for a woman

to have a career as a published poet than hitherto. That it did not produce an

answering radicalism within Hemans’s work may mean nothing more than that she

was already taking a radical step in living as a writer.

But

there’s something else setting the teeth on edge here: something much more like

false consciousness, even denial. Hemans continues:

The

Cottage Homes of England!

By

thousands on her plains,

They are

smiling o’er the silvery brooks,

And

round the hamlet-lanes.

Thro’

glowing orchards forth they peep,

Each

from its nook of leaves,

And

fearless there the lowly sleep

As the

bird beneath the eaves.

Yet, as

she would have known perfectly well, early 19th-century cottages were unlikely

to ‘smile’ even through the mask of a transferred epithet. The Romantic era

arrived in a perfect storm of hardship for the British poor. Wealth

inequalities, already enshrined in the class system, were being underscored by

the onset of imperial expansion, which may have brought the wealth of the world

to Britain, but did not yet bring it to the majority of the population, whom it

instead impoverished relatively further still: when the rich have more money to

pay for things, the price even of staples rises. Underscored too by new

manufacturing and business wealth. The era’s fortune-making industrial

revolution was built on discoveries by the new Romantic science, from

map-making (the Ordnance Survey was established in 1791) to James Watt’s 1776

adaptation of a steam engine suitable for use in industrialisation. But the

labour that fuelled the industrial revolution was supplied by mass migration of

the rural poor, in a process that became the model for world industrialisation.

Peculiarly

British, though, was the application of Romantic ideas to an

already-accelerating para-legal process of Enclosure by estate landlords (aka,

the aristocracy), which now cleared ordinary people off the common land on

which their traditional subsistence farming had relied. Its twin motors were

the agricultural revolution, and the fashion for picturesque, sublime and

beautiful parkland. Once the gentry began to invest in the era’s new

agricultural methods and machinery – such as seed-drills and horse-drawn hoes

after the designs by Jethro Tull – they became eager to protect that

investment. Between 1815 and 1846 a series of tariffs on imported wheat and all

grains, the infamous Corn Laws, were enacted in the British Parliament: whose

Members were drawn from this class. The resulting cost and scarcity of the

staple food of the poor led to widespread destitution and starvation across

Britain.

Meanwhile,

since the 18th century, the same class had surrounded their ‘stately’ homes

with newly landscaped parks, conspicuous consumers of agricultural land that

formerly supported whole villages. Despite the social injustice this involved,

Romanticism aided rather than resisted the process. In 1757, Edmund Burke, that

Whig politician with a politically conservative legacy, had published his

influential essay in aesthetics, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our

Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Adopting these categories, British

Romanticism might have remained content to see them act upon the newly

significant, sensitive individual, were it not for a pair of Herefordshire

landowners.

In the

mid-1790s, Sir Uvedale Price and Richard Payne Knight joined the artist-pioneer

William Gilpin in advocating the picturesque, hitherto a principle of French

gardening, as a quality that could be discovered and arranged within the

landscape itself. Their legacy was to be not only the rise of the ultimately

democratic tourist industry, but also numerous newly enclosed parks that

imposed vistas of trees and lakes on the old ruled landscapes of strip farming.

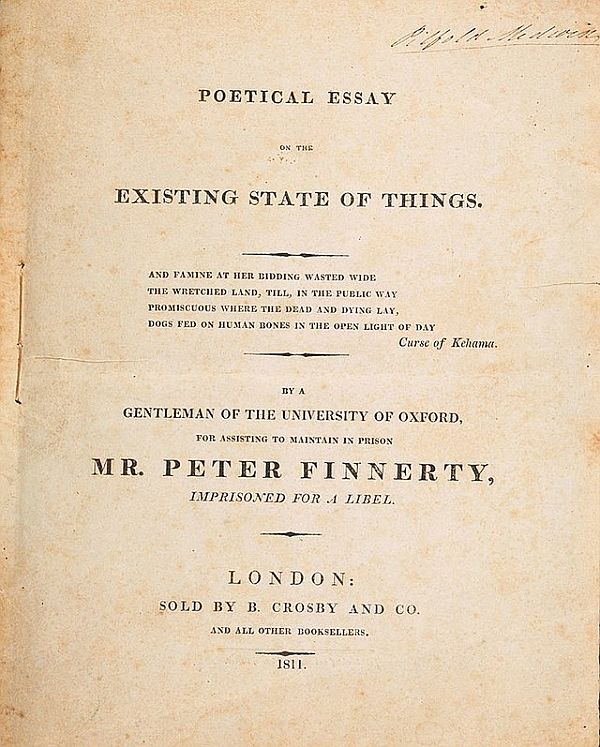

It’s as

if the process of drawing the teeth of Romanticism’s radical ideas was underway

from the very outset. Real life sullied and seemed to contradict Romanticism’s

ideals. After being sent down from Oxford in 1811, the 18-year-old Percy Bysshe

Shelley stayed in mid-Wales with an uncle who had created just such a landscape

on his property:

Rocks

piled on each other to tremendous heights, rivers formed into cataracts by

their projections, & valleys clothed with woods, present an appearance of

enchantment—but why do they enchant, why is it more affecting than a plain, it

cannot be innate, is it acquired?

The very

next year saw the young radical in Ireland, pamphleteering for Irish autonomy

and the franchise for Roman Catholics; in 1813, with the publication of Queen

Mab, his Notes advocating pacifist vegetarianism appeared. Yet his lifelong

reliance on money from his Sussex estate-owning family meant complicity in the

era’s agricultural reforms, and in the aristocratic privileges surrounding the

baronetcy to which he was heir. Nor was his reliance on such social inequity to

enable his Romantic activity unique in what was also the era of Lord Byron’s

literary celebrity. A little later still, the abolitionist Barrett Browning’s

own family had profited from slavery.

And yet.

As individuals, we do our best among the contradictions of situatedness.

Barrett Browning used her literary fame to become a mouthpiece not only of

abolitionism in the United States, but of the Italian republican struggle. For

this, Florence buried her with full civic honours.

Five

years after that formative encounter with the picturesque in the mountains of

the Elenydd, we find Shelley composing ‘Hymn to Intellectual Beauty’ (1817),

one of the first poems of his maturity, in which not only picturesque

principles but the nature of experience itself are being worked out:

The

awful shadow of some unseen Power

Floats

though unseen among us; visiting

This

various world with as inconstant wing

As

summer winds that creep from flower to flower;

Like

moonbeams that behind some piny mountain shower,

It

visits with inconstant glance

Each

human heart and countenance …

For

Romanticism saw itself as not only a kind of High Table talking shop, but an

actual agent of change. Witness Shelley’s fury at the older Wordsworth,

fabulised in his 772-line Peter Bell the Third (1819), for selling out to the

status quo:

To

Peter’s view, all seemed one hue;

He was

no Whig, he was no Tory;

No Deist

and no Christian he, –

He got

so subtle, that to be

Nothing,

was all his glory.

…

He hired

a house, bought plate, and made

A

genteel drive up to his door,

With

sifted gravel neatly laid, –

As if

defying all who said,

Peter

was ever poor.

Yet in

settling their households in neighbourly community in the Lake District, Dorothy

and William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey and Thomas De

Quincey created the precursor of those more radically reformed ideal

communities – from Portmeirion on the Welsh coast, to Uri in Switzerland – with

which the Shelleys and, to an extent, the Leigh Hunts and James Hoggs,

experimented – and to which 20th-century hippies and today’s off-grid

communities are heir. And it was Wordsworth’s collaborative friendship with

Coleridge that had from 1795 helped sew the ideas of German Idealist

philosophers including Hegel and F W J Schelling into the culture that

Shelley’s generation absorbed. Shelley’s reaction against the British poet

laureate who was his Romantic predecessor is itself a nice fit with Hegel’s

idea of history as dialectical progress.

And it

is Wordsworth, the elder poet, whose ecological and political awareness remains

most directly legible to us today: from ‘On Seeing Miss Helen Maria Williams

Weep at a Tale of Distress’ (1787), the poem he published at 16 declaring his

adherence to the new principle of ‘sensibility’, to his posthumous masterpiece

The Prelude (1850) – that portrait of the artist as a village. Drawing the

sting of psychological insight from Wordsworth’s ‘I wandered lonely’ or denying

Constable’s insight into the linked conditions of climate and labour leaves us

with little more than wildflowers in the English Lake District, or a cottage by

an East Anglian ford. Prettiness: that most vacuous of principles.

An

irony, then, to appropriate Romanticism to represent as a national specific,

let alone as some version of a ‘timeless’ rural Britain. Romanticism records

not the cosy continuity for which it is so often recruited: but the very moment

when that continuity was broken. But it’s not just the muddle of individual

human compromise that creates the vacuum in place of radical intention. The

rise of the alt-Right reminds us how politically dangerous it is to base a

nation’s view of itself on some version of a past that was white, feudal,

Christian. At the very least, a disarmed Romanticism resembles that anaesthetic

of political conservativism that the UK’s former prime minister John Major

sought to apply to the Conservative Group for Europe in 1993, when he

notoriously evoked:

long

shadows on county grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers, and

– as George Orwell said – old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the

morning mist.

Which,

given Orwell’s own political vision, is a pretty bold reappropriation. But the

de-radicalisation of Romanticism hasn’t been achieved only by political

process. The market, too, has something of the conservative about it. Though it

trumpets the new, it thrives on settled habits of consumption. Repeating the

familiar suits it just fine. It may even prefer its consumers a little bored,

as they sleepwalk back to the gift shop.

Sleepwalk

to the gift shop. Romanticism once

radically challenged conventional pieties. Now it’s little more than marketable

schlock. What happened? By Fiona

Sampson. Aeon, July 8, 2022.