George Berkeley is known for his doctrine of immaterialism: the counterintuitive view that there’s no material substance underlying the ideas perceived by the senses. We tend to think of a horse-drawn coach as a thing, but Berkeley tells us it’s really a set of ideas – the sound of the coach in the street, the sight of it through a window, the feel of it as we get in. We regularly perceive these ideas going along with each other, but there’s no material thing, beyond the ideas, that supports or holds them together – the ideas are all there is. It’s a hard view for a present-day reader to stomach. It was hard on the stomachs of readers even in Berkeley’s day in the early 1700s. He acknowledged that ‘it sounds very harsh to say we eat and drink ideas’ but insists that nourishment is nothing more than various ideas of the senses.

Conformity

brings spiritual rewards. It also brings temporal privileges. As Berkeley said

in an early sermon on zeal: ‘As we are Christians we are members of a Society

which entitles us to certain rights and privileges above the rest of mankind.’

In his ‘Address on Confirmation’, Berkeley said that, while the whole world

might be understood as the kingdom of Christ, the phrase also had a more

restrictive sense and applied to ‘a Society of persons, not only subject to his

power, but also conforming themselves to his will, living according to his

precepts, and thereby entitled to the promises of his gospel.’ That is, when

Berkeley talked about the phenomenal world of ideas forming an instructive

discourse directed to us by God, the God he had in mind requires conformity to

his will. Greater or lesser degrees of conformity result in privileges

expressed in the social and religious hierarchy of this world.

The God

who produces the immaterial world, then, requires specific behaviours of

different kinds of people, and grants them specific privileges. The distinction

is not just between Christians and non-Christians, but between various types

and classes of person in Christian societies. Here Berkeley is quite in line

with his times and the large number of books dedicated to differentiating and

specifying the duties of types and classes of people – children, parents,

spouses, magistrates and so on. Berkeley’s sense of stratification and distinction

by social status or rank is most obvious in his economic writings of the

mid-1730s, chiefly the three volumes of rhetorical questions called The

Querist, which put forward a programme for Irish economic renewal. The

(‘native’, Catholic) peasantry are to give up their alleged sloth and dirtiness

for habits of cleanliness and industry. The (absentee, Protestant) gentry are

to give up imported wines and textiles for Irish cider and linen. Both classes

will find they have higher desires – the peasants for beef and better clothes;

the gentry for local productions of the fine and useful arts. A national bank

will support the increased rate of circulation in the economy, or its momentum,

as Berkeley calls it. And a class of philosophical educators such as Berkeley

himself will manage the necessary transformation of opinions, desires and

practices, chiefly by educating the gentry. Different classes of people – the

higher, the lower, the educators – have different roles in practising and

producing conformity to God’s will.

All

classes of people have responsibilities to God that are in part expressed

through their behaviour towards their own and other classes of people.

‘Charity’ is the term that, for Berkeley, captures the fulfilment of these

responsibilities. He preached on charity at the English merchant colony in

Livorno in Italy in 1714, saying – perhaps with an eye to the background of his

audience – that the mutual satisfaction of wants through commerce was a form of

charitable action within the reach of all. Duty to God and charity to his

neighbour will make the true Christian attempt the conversion of heathens and

infidels, Berkeley said in the sermon he preached to the Society for

Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts on his return from his failed expedition

to found a university in Bermuda. That project was itself geared towards the

conversion of Native Americans, as well as the religious reform of white

colonists.

May 2021

marks the publication of a major new intellectual biography of Bishop George

Berkeley by Tom Jones (University of St Andrews), George Berkeley: A

Philosophical Life (Princeton University Press, 2021). Trinity Long Room Hub is

pleased to host a conversation with Dr Jones that will centre on Berkeley’s

life, connections to Trinity and Ireland, and his relationship to colonialism

as he moved between the ‘new’ world and the ‘old’.

George Berkeley, Colonialism, and Ireland: A Conversation with Tom Jones. TLR Hub , May 19, 2021

George Berkeley, Colonialism, and Ireland: A Conversation with Tom Jones. TLR Hub , May 19, 2021

The days

of uncritically lionising great men of western civilisation are coming to an

end. Some see this as a threat to social order but surely hero-worshipping was

never a good idea, given that every man – after a certain length of time –

starts to resemble an embarrassing uncle.

Go back

a few hundred years and it’s hard to find a European writer who didn’t have

views on race or gender that we would today consider backward.

Last

month, this column queried the rap sheet against Enlightenment thinker David

Hume but there’s a more troubling case closer to home. The “good bishop” George

Berkeley (1685-1753), who is synonymous with Trinity College Dublin (TCD), is

widely regarded as Ireland's great philosopher but recently he has attracted

negative attention due to his ownership of slaves while doing missionary work

in Rhode Island.

Last

February, TCD launched a two-year investigation into the college’s “complex

colonial legacies” – a project that will be greatly aided by a new biography of

the Co Kilkenny-born Berkeley by Tom Jones.

George

Berkeley: A Philosophical Life is not only a meticulously researched and

clear-sighted assessment of the philosopher’s character, it also measures the

weight of his “revolutionary” ideas. Jones, a long-standing Berkeley scholar

who is based at University of St Andrews, Scotland, describes the process of

biography as trying to avoid the traps of both hagiography and “attributing a

great or even implausible degree of internal coherence to a particular life”.

Berkeley

was a man of contradictions - a social reformer heavily engaged in charitable

works and prescient in advocating the public ownership of banks to curb

reckless speculation but he also believed strongly in obedience to hierarchy.

Jones explores these incongruities further as this week’s Unthinkable guest.

JH : You’ve

written extensively on Berkeley over the years but how did this particular

project come about?

TJ : “There

hadn’t been a book-length biography of Berkeley since 1949, so I wanted to

bring together all of the material that different scholars and historians had

discovered since then, and add my own researches to see what picture of

Berkeley emerged.

“There

were also two things that it seemed to me no biography had ever attempted

before. The first was to show how other people and institutions – family,

schools, colleges, societies, the church – shaped Berkeley’s beliefs and

actions. The second was how Berkeley’s philosophy related to his practical life

– as a teacher, churchman, family man and social activist.

“Berkeley’s

life in education is a good illustration of these points. I think he was very

strongly shaped by the orderly and emphatically Protestant environment of

Kilkenny College and Trinity College. He took a lifelong interest in educating

others – students at Trinity, his own – male and female – children, the

children of colonial Americans, Native Americans and African-Americans.

“Berkeley’s

wife continued to educate and guide her children after his death, frequently

citing his example. So I tried to tell a story of Berkeley’s life that showed

how his striking and individual philosophical beliefs were woven in and out of

his relationships with other people, and how his active life was tied up with

his contemplative life.”

JH : Is

it fair to say that, to the extent that Berkeley was interested in the

condition of slaves, it was on the narrow point of whether or not they should

be baptised?

TJ : “Slavery

is a subject Berkeley only touches on a few times in his writings, and what we

know of his practical involvement in the question of slavery could be

interpreted in various ways, so this is a complex issue.

“It is

important to acknowledge that Berkeley never openly questions the legitimacy of

the system of chattel slavery, that he bought enslaved people, and that he was

therefore involved in this great historic crime – as were, more or less

directly, many British subjects of his era.

“Baptism

is, indeed, what seems most to concern Berkeley about slavery... For him,

however, baptism is not a narrow point, but a key element of human dignity.

Being admitted to religious instruction and the rites of the church was being

recognised as human where it mattered most, in Berkeley’s view.

“In his

writing on economic questions Berkeley blurs distinctions between servitude and

slavery. That can have the effect of legitimising slavery. But it can also be

an argument that slavery shouldn’t be more punitive than servitude, or exclude

enslaved people from recognition of their humanity. So when Berkeley baptised

Philip, Anthony and Agnes Berkeley, identified as ‘his negroes’, he was doing

something he would have regarded as a recognition of the most important aspect

of those people’s humanity.

“There

don’t appear to be records of baptisms of any other people of African heritage

in the same church in Berkeley’s two years in Rhode Island – not that skin

colour would necessarily have been consistently noted in such records – so he

might have been making quite an unusual and visible statement. So, whilst this

is a narrow concern from one perspective, it is also testimony to a concern for

the religious education of African people in America.”

JH : Was

Berkeley just “a man of his time” in respect to defending slavery or was there

something more much calculating going on?

TJ : “One

thing I try to do in the biography is compare Berkeley’s views to those of

other people and groups of his time, and the one group that is actively

organising against the institution of slavery in the late 1720s is the Quaker

community – as Brycchan Carey has shown. Berkeley does not challenge the

existence of the institution, and indeed points out ways in which it is

compatible with his aims of religious conversion and instruction.

“He

doesn’t defend slavery by saying that it is all certain groups of people are

fit for, or that it is a property right that cannot be challenged. His defence

is more that slavery is like servitude, and it may be better – in his view – to

be obliged to serve a greater good than to be free and live a life that seems

to go against God’s intentions for humanity.

“It’s

useful to compare Berkeley’s thinking about the Catholic population of Ireland

here. Late in life he compared the ‘native’ Irish both to Africans in America

and to Native Americans, saying their conditions of life were savage and

abject. He suggested that a way for Irish peasants to avoid a degrading life of

dirt, sloth and beggary was for them to be seized and made ‘slaves to the

public’ for a period of time.

“So

there is a calculation going on that involves asking whether it’s better to be

free and degraded, or enslaved but orderly and productive. For Berkeley, that

participation in social order was really central to being human.”

JH : You

say there is no record of what happened to the people Berkeley purchased. Is it

possible they were brought to Ireland?

TJ : “It

is possible that the people Berkeley bought in America came to London and then

Ireland with him and his family, although there is no evidence either way. The

historian Patrick Kelly noticed that a set of reading cards for children

referred to two of Berkeley’s servants at this time by name – Patrick Norway

and Enoch Martyr. So these are not the same people as were baptised by Berkeley

in America.

“In

occasional references to Berkeley’s servants in letters and other documents no

mention is made of a servant of African heritage – though again ethnic

background might not always have been mentioned in such papers.

“One

historian puts the black population of Ireland in the second half of the 18th

century between 1,000 and 3,000. It seems likely that some of these people

arrived in Ireland with families by whom they were owned or for whom they

worked, across the Irish sea or the Atlantic. The people Berkeley bought could

have been among them.”

JH : Of

Berkeley’s philosophy, you comment in the book: “There was something

revolutionary about his immaterialism, but it was one of those conservative

revolutions that seeks to leave things as they are.” For all his philosophical

innovation, was Berkeley ultimately engaged in a very reactionary religious

project?

TJ : “Berkeley’s

religious project was radical in asserting the entire dependence of the

universe on the will of a superior being, God. It’s radical because Berkeley

says we are dependent on God for all the ideas conveyed by our senses – not on

matter that lies behind and provokes ideas or sensations...

“It’s a

striking picture of God constantly talking to his creatures through the

creation itself. The central feature of this religious view of the world is

dependence on a superior will, though, and it echoes through Berkeley’s social

and political thought. He believed lower sorts of people ought to trust to the

higher sort to govern, and to religious educators to mediate ideas they could

not expect to grasp themselves. So hierarchy is built into Berkeley’s view of

the world, by analogy with his religious vision.

“Many

other political and religious thinkers of the 18th century held similar views,

but none of them in the unique combination of immaterialist metaphysics,

religious vision and social reform that characterise Berkeley.”

George

Berkeley: A Philosophical Life by Tom Jones is published by Princeton.

Was

Ireland’s greatest philosopher a hero, villain or ‘man of his time’? By Joe

Humphreys. The Irish Times , July 15, 2021.

George

Berkeley is one of the greatest philosophers of the early modern era. Along

with John Locke and David Hume, he was a founder of Empiricism, which

championed the role of experience and observation in the acquisition of

knowledge. He influenced Kant and John Stuart Mill, and even pre-empted

elements of Wittgenstein. His book The Principles of Human Knowledge is a

masterwork still set on university philosophy courses the world over, and

indeed there is a famous university named after him in California. The

celebrated Irishman even inspired a limerick.

Yet Berkeley is also widely misunderstood. Different aspects of his thinking, not to mention his character, seem to clash quite spectacularly. His most famous doctrine was viewed as heretical in its day, yet Berkeley was a bishop and fierce believer in the supremacy of the Anglican church. He simultaneously advanced radically counter-intuitive and staunchly conservative arguments. He was a passionate social reformer but was complicit in appalling social evils. This makes Berkeley a fascinating subject. He appears a study in contradiction—but stick with him long enough and you realise that maybe there is no contradiction at all.

Tom Jones, an academic at the University of St Andrews, is well qualified to tell the story, having spent years researching and publishing on the life and work of this multi-faceted thinker. Here, over 550 richly detailed pages, he carefully explains how the different parts might fit together. It is a project of some importance, because you can only assess a thinker’s worth by seeking to understand them in the round.

Born in south-east Ireland in 1685, Berkeley studied at Kilkenny College and then Trinity College Dublin. He entered a world of ideas recently transformed by the likes of Descartes, Locke and Malebranche, and was publishing from his early twenties, when he developed the theory that would come to define him in the public imagination: immaterialism, the view that matter does not actually exist and all objects are in the mind.

The intuitive view tells us that when we perceive an object, our perception connects to something “out there” in the external world. When I look out of the window and form the image of a tree in my mind, I assume there is a lump of matter in the garden lying behind the image—namely the tree. There may be questions over the nature of the relationship between the tree and my perception of it—and these were interrogated in depth by Berkeley’s contemporaries—but the idea that the tree exists in material form was not disputed. Locke had said: “the certainty of things existing in rerum natura, when we have the testimony of our senses for it, is not only as great as our frame can attain to, but as our condition needs.”

Yet for Berkeley there was no reason to assume the existence of a material object at all. When we think we perceive the tree, what information do we have? Nothing beyond the perceptions themselves: sense data of its shape, size, colour and so on. This sense data, for Berkeley, is what constitutes the object. To most people it seems like a radically sceptical view, perhaps even more so than doubting the existence of free will or objective moral laws. But Berkeley, advancing the theory chiefly in his Principles and the Socratic dialogue Hylas and Philonous, thought it was precisely the opposite. Like Locke, he stressed the role of sensory perception in human knowledge, but took this position to its logical conclusion: when something is unperceived, it ceases to be. The famous question of whether a falling tree makes a sound if no one is around to hear it is inspired by Berkeley.

In Berkeley’s conception, the only things that exist are spirits (of which God is the greatest), minds and ideas.

This was not a universally popular theory. Pope, otherwise an admirer, called it “the most outrageous whimsy that ever entered into the head of any ancient or modern madman.” Boswell described a conversation with Johnson: “we stood talking for some time together of Bishop Berkeley’s ingenious sophistry to prove the non-existence of matter, and that every thing in the universe is merely ideal. I observed that though we are satisfied, his doctrine is not true, it is impossible to refute it. I never shall forget the alacrity with which Johnson answered, striking his foot with mighty force against a large stone, till he rebounded from it, ‘I refute it thus.’” Johnson was appealing to the common-sense view that matter—the rock—exists, and in this case has obvious solidity.

It was immaterialism that earned Berkeley his reputation as an iconoclast. But what at first glance seems revolutionary is in fact another facet to Berkeley’s profoundly conservative disposition. His is the story of a reactionary coming full circle.

Objectionable social attitudes are elevated to philosophy in Berkeley’s reflections on hierarchy and social order. He believed that subordination to our betters is a good in itself. Unreflective obedience is not just right and proper but speaks to humanity’s participation in the divinity: life is structured around order, regularity and chains of command, with God at the top. It is right that human societies echo this in their own relations—be it sovereign and subject, master and servant or husband and wife.

This extends to slavery. Berkeley owned slaves and wrote in support of the practice. He may even, possibly inadvertently, have helped solicit the infamous Yorke-Talbot opinion from the British law officers, which served as a legal bulwark for slavery throughout the British Empire. Berkeley was not much more enlightened in his views towards Irish Catholics, whom he regarded as innately inferior to their Protestant compatriots. He advanced the primacy of the Anglican church with literally missionary zeal at home and overseas, planning unsuccessfully for several years to found a college in the Americas to spread the gospel.

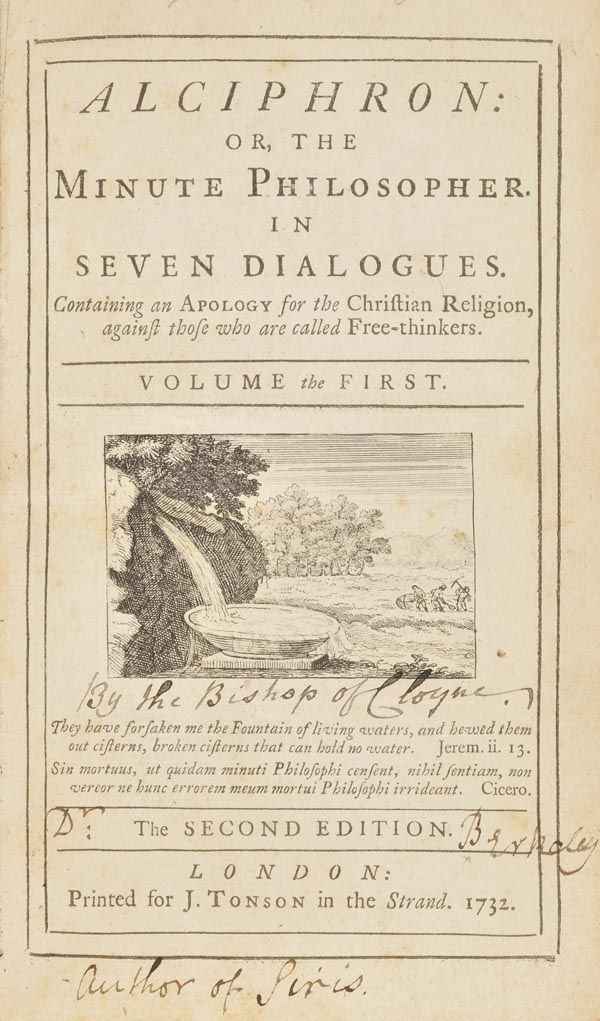

In his daily life the most important figure was God, and his chief intellectual opponents were the “free thinkers” whose irreligion he condemned in his Christian apologetic Alciphron.

Despite the heretical appearance of immaterialism, Berkeley didn’t actually believe he was facilitating scepticism, let alone atheism. In fact, while for him God did not create the world in a material sense, he lies behind all of our ideas, imprinting them on our minds. Berkeley’s system thus retains God as the ultimate cause and creates an intimacy with the deity which can form the basis for our moral judgments. He wrote that his philosophical project was “directed to practise and morality, as appears first from making manifest the nearness and omnipresence of God.”

For Berkeley, the real problem arises if we take the existence of matter as a given. Then we have to describe the relationship between our perceptions and the external world, and admit the possibility of disharmony between the two. In this gap there is the room for doubt: why think that what I see, feel or smell accurately corresponds to what is “out there”? This is “the very root of scepticism,” he writes, for whether our ideas “represent the true quality really existing in the thing, it is out of our reach to determine.”

His ingenious solution was to circumvent the problem completely, by collapsing one category into the other: if you identify the object and sensory experience of it as one and the same, the room for scepticism disappears. Immaterialism is thus, in Berkeley’s framing, a solution to sceptical doubt rather than an example of it. It is specifically designed to dispel “impious notions.”

That is not to say Berkeley was home and dry. Some asked how hallucinations fit into his picture, alleging that they sever the link between ideas and reality in some distinct way his system cannot account for. Another classic objection has it that the corollary of believing that things do not exist unless they are being perceived is that objects must be continually popping in and out of existence depending on whether they are being looked at or not, which is metaphysically untidy to say the least.

The response available to Berkeley is to argue that God is a perceiver too, and that it is unlikely that God has stopped perceiving the tree. This point is captured in a limerick attributed to 20th-century theologian Ronald Knox:

There was a young man who said “God

Must find it exceedingly odd

To think that the tree

Should continue to be

When there’s no one about in the quad.”

Reply:

“Dear Sir: Your astonishment’s odd;

I am always about in the quad.

And that’s why the tree

Will continue to be

Since observed by, Yours faithfully, God.”

The conservatism underlying the immaterialist philosophy becomes clearer when you realise that in the final analysis, it tells us that there is a tree in the quad, and that the rational agent perceives it accurately. Berkeley writes: “my speculations have the same effect as visiting forein countries, in the end I return where I was before, set my head at ease and enjoy my self with more satisfaction.” The exercise is a clarificatory one, aimed not at demolishing our current understanding but improving it, thus enhancing our relish of the world God has provided for us—and leaving its inequalities intact.

Jones is an authoritative tour guide through all of this. He admits from the outset that constructing a unified portrait from inevitably fragmented historic evidence is challenging, made more difficult still when comparing the different elements of such a complicated thinker. The end result, carefully written and impeccably well researched, is a must-read for those with a background in philosophy. Some passages will be intimidatingly complex to beginners, especially given the book is not strictly chronological, while the focus can stray towards areas that you suspect Jones is interested in personally (such as Berkeley’s belief in the medicinal properties of tar water) rather than having been written with the general reader in mind. None of this changes the fact the book is overwhelmingly a success.

What Jones has revealed is the fascinating combination of chaos and coherence laced through Berkeley’s life. What was his ultimate contribution? For Schopenhauer, Berkeley was “the first to treat the subjective starting-point really seriously and to demonstrate irrefutably its absolute necessity.” Much great philosophy followed from this, both in support of and opposition to Berkeley’s ideas, with Kant’s “transcendental idealism”—stressing the role of perception in our knowledge of the world, and like Berkeley’s theory aimed at combatting scepticism—perhaps the most famous example. To this day, even if you think Berkeley’s metaphysics is wrong it can be difficult to explain precisely why. And there is so much more to explore, including highly original contributions to the philosophy of science and language. Berkeley was not a perfect thinker and his philosophy will remain the subject of misconceptions. But it overflows with riches.

Mind over matter: the contradictions of George Berkeley. By Alex Dean. Prospect Magazine, May 25, 2021.

Yet Berkeley is also widely misunderstood. Different aspects of his thinking, not to mention his character, seem to clash quite spectacularly. His most famous doctrine was viewed as heretical in its day, yet Berkeley was a bishop and fierce believer in the supremacy of the Anglican church. He simultaneously advanced radically counter-intuitive and staunchly conservative arguments. He was a passionate social reformer but was complicit in appalling social evils. This makes Berkeley a fascinating subject. He appears a study in contradiction—but stick with him long enough and you realise that maybe there is no contradiction at all.

Tom Jones, an academic at the University of St Andrews, is well qualified to tell the story, having spent years researching and publishing on the life and work of this multi-faceted thinker. Here, over 550 richly detailed pages, he carefully explains how the different parts might fit together. It is a project of some importance, because you can only assess a thinker’s worth by seeking to understand them in the round.

Born in south-east Ireland in 1685, Berkeley studied at Kilkenny College and then Trinity College Dublin. He entered a world of ideas recently transformed by the likes of Descartes, Locke and Malebranche, and was publishing from his early twenties, when he developed the theory that would come to define him in the public imagination: immaterialism, the view that matter does not actually exist and all objects are in the mind.

The intuitive view tells us that when we perceive an object, our perception connects to something “out there” in the external world. When I look out of the window and form the image of a tree in my mind, I assume there is a lump of matter in the garden lying behind the image—namely the tree. There may be questions over the nature of the relationship between the tree and my perception of it—and these were interrogated in depth by Berkeley’s contemporaries—but the idea that the tree exists in material form was not disputed. Locke had said: “the certainty of things existing in rerum natura, when we have the testimony of our senses for it, is not only as great as our frame can attain to, but as our condition needs.”

Yet for Berkeley there was no reason to assume the existence of a material object at all. When we think we perceive the tree, what information do we have? Nothing beyond the perceptions themselves: sense data of its shape, size, colour and so on. This sense data, for Berkeley, is what constitutes the object. To most people it seems like a radically sceptical view, perhaps even more so than doubting the existence of free will or objective moral laws. But Berkeley, advancing the theory chiefly in his Principles and the Socratic dialogue Hylas and Philonous, thought it was precisely the opposite. Like Locke, he stressed the role of sensory perception in human knowledge, but took this position to its logical conclusion: when something is unperceived, it ceases to be. The famous question of whether a falling tree makes a sound if no one is around to hear it is inspired by Berkeley.

In Berkeley’s conception, the only things that exist are spirits (of which God is the greatest), minds and ideas.

This was not a universally popular theory. Pope, otherwise an admirer, called it “the most outrageous whimsy that ever entered into the head of any ancient or modern madman.” Boswell described a conversation with Johnson: “we stood talking for some time together of Bishop Berkeley’s ingenious sophistry to prove the non-existence of matter, and that every thing in the universe is merely ideal. I observed that though we are satisfied, his doctrine is not true, it is impossible to refute it. I never shall forget the alacrity with which Johnson answered, striking his foot with mighty force against a large stone, till he rebounded from it, ‘I refute it thus.’” Johnson was appealing to the common-sense view that matter—the rock—exists, and in this case has obvious solidity.

It was immaterialism that earned Berkeley his reputation as an iconoclast. But what at first glance seems revolutionary is in fact another facet to Berkeley’s profoundly conservative disposition. His is the story of a reactionary coming full circle.

Objectionable social attitudes are elevated to philosophy in Berkeley’s reflections on hierarchy and social order. He believed that subordination to our betters is a good in itself. Unreflective obedience is not just right and proper but speaks to humanity’s participation in the divinity: life is structured around order, regularity and chains of command, with God at the top. It is right that human societies echo this in their own relations—be it sovereign and subject, master and servant or husband and wife.

This extends to slavery. Berkeley owned slaves and wrote in support of the practice. He may even, possibly inadvertently, have helped solicit the infamous Yorke-Talbot opinion from the British law officers, which served as a legal bulwark for slavery throughout the British Empire. Berkeley was not much more enlightened in his views towards Irish Catholics, whom he regarded as innately inferior to their Protestant compatriots. He advanced the primacy of the Anglican church with literally missionary zeal at home and overseas, planning unsuccessfully for several years to found a college in the Americas to spread the gospel.

In his daily life the most important figure was God, and his chief intellectual opponents were the “free thinkers” whose irreligion he condemned in his Christian apologetic Alciphron.

Despite the heretical appearance of immaterialism, Berkeley didn’t actually believe he was facilitating scepticism, let alone atheism. In fact, while for him God did not create the world in a material sense, he lies behind all of our ideas, imprinting them on our minds. Berkeley’s system thus retains God as the ultimate cause and creates an intimacy with the deity which can form the basis for our moral judgments. He wrote that his philosophical project was “directed to practise and morality, as appears first from making manifest the nearness and omnipresence of God.”

For Berkeley, the real problem arises if we take the existence of matter as a given. Then we have to describe the relationship between our perceptions and the external world, and admit the possibility of disharmony between the two. In this gap there is the room for doubt: why think that what I see, feel or smell accurately corresponds to what is “out there”? This is “the very root of scepticism,” he writes, for whether our ideas “represent the true quality really existing in the thing, it is out of our reach to determine.”

His ingenious solution was to circumvent the problem completely, by collapsing one category into the other: if you identify the object and sensory experience of it as one and the same, the room for scepticism disappears. Immaterialism is thus, in Berkeley’s framing, a solution to sceptical doubt rather than an example of it. It is specifically designed to dispel “impious notions.”

That is not to say Berkeley was home and dry. Some asked how hallucinations fit into his picture, alleging that they sever the link between ideas and reality in some distinct way his system cannot account for. Another classic objection has it that the corollary of believing that things do not exist unless they are being perceived is that objects must be continually popping in and out of existence depending on whether they are being looked at or not, which is metaphysically untidy to say the least.

The response available to Berkeley is to argue that God is a perceiver too, and that it is unlikely that God has stopped perceiving the tree. This point is captured in a limerick attributed to 20th-century theologian Ronald Knox:

There was a young man who said “God

Must find it exceedingly odd

To think that the tree

Should continue to be

When there’s no one about in the quad.”

Reply:

“Dear Sir: Your astonishment’s odd;

I am always about in the quad.

And that’s why the tree

Will continue to be

Since observed by, Yours faithfully, God.”

The conservatism underlying the immaterialist philosophy becomes clearer when you realise that in the final analysis, it tells us that there is a tree in the quad, and that the rational agent perceives it accurately. Berkeley writes: “my speculations have the same effect as visiting forein countries, in the end I return where I was before, set my head at ease and enjoy my self with more satisfaction.” The exercise is a clarificatory one, aimed not at demolishing our current understanding but improving it, thus enhancing our relish of the world God has provided for us—and leaving its inequalities intact.

Jones is an authoritative tour guide through all of this. He admits from the outset that constructing a unified portrait from inevitably fragmented historic evidence is challenging, made more difficult still when comparing the different elements of such a complicated thinker. The end result, carefully written and impeccably well researched, is a must-read for those with a background in philosophy. Some passages will be intimidatingly complex to beginners, especially given the book is not strictly chronological, while the focus can stray towards areas that you suspect Jones is interested in personally (such as Berkeley’s belief in the medicinal properties of tar water) rather than having been written with the general reader in mind. None of this changes the fact the book is overwhelmingly a success.

What Jones has revealed is the fascinating combination of chaos and coherence laced through Berkeley’s life. What was his ultimate contribution? For Schopenhauer, Berkeley was “the first to treat the subjective starting-point really seriously and to demonstrate irrefutably its absolute necessity.” Much great philosophy followed from this, both in support of and opposition to Berkeley’s ideas, with Kant’s “transcendental idealism”—stressing the role of perception in our knowledge of the world, and like Berkeley’s theory aimed at combatting scepticism—perhaps the most famous example. To this day, even if you think Berkeley’s metaphysics is wrong it can be difficult to explain precisely why. And there is so much more to explore, including highly original contributions to the philosophy of science and language. Berkeley was not a perfect thinker and his philosophy will remain the subject of misconceptions. But it overflows with riches.

Mind over matter: the contradictions of George Berkeley. By Alex Dean. Prospect Magazine, May 25, 2021.

No comments:

Post a Comment