Of all

the world religions, Buddhism enjoys the greatest respect and popularity among

those who seek a model for “spiritual life” beyond traditional religion. Even

the prominent atheist Sam Harris turns to the meditational exercises of

Buddhism in his best-selling book “Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without

Religion.” This is understandable, since Buddhist meditation practices can be

employed to great effect for secular ends. In particular, there has been

success in adapting various forms of meditation techniques for cognitive

therapy as well as for practical forms of compassion training. If you learn

Buddhist meditation techniques for such therapeutic purposes — or simply for

the sake of having more strength and energy — then you are adapting the

techniques for a secular project. You engage in meditational practices as a

means for the end of deepening your ability to care for others and improving

the quality of your life.

The aim

of salvation in Buddhism, however, is to be released from finite life itself.

Such an idea of salvation recurs across the world religions, but in many

strands of Buddhism there is a remarkable honesty regarding the implications of

salvation. Rather than promising that your life will continue, or that you will

see your loved ones again, the salvation of nirvana entails your extinction.

The aim is not to lead a free life, with the pain and suffering that such a

life entails, but to reach the “insight” that personal agency is an illusion

and dissolve in the timelessness of nirvana. What ultimately matters is to

attain a state of consciousness where everything ceases to matter, so that one

can rest in peace.

The

Buddhist conclusion may seem extreme when stated in this way, but in fact it

makes explicit what is implicit in all ideas of eternal salvation. Far from

making our lives meaningful, eternity would make them meaningless, since our

actions would have no purpose. This problem can be traced even within religious

traditions that espouse faith in eternal life. An article in U.S. Catholic

asks: “Heaven: Will it be Boring?” The article answers no, for in heaven souls

are called “not to eternal rest but to eternal activity — eternal social

concern.” Yet this answer only underlines the problem, since there is nothing

to be concerned about in heaven.

Concern

presupposes that something can go wrong or can be lost; otherwise we would not

care. An eternal activity — just as much as an eternal rest — is of concern to

no one, since it cannot be stopped and does not have to be maintained by

anyone. The problem is not that an eternal activity would be “boring” but that

it would not be intelligible as my activity. Any activity of mine (including a

boring activity) requires that I sustain it. In an eternal activity, there

cannot be a person who is bored — or involved in any other way — since an

eternal activity does not depend on being sustained by anyone.

An

eternal salvation is therefore not only unattainable but also undesirable,

since it would eliminate the care and passion that animates our lives. What we

do and what we love can matter to us only because we understand ourselves as

mortal. That self-understanding is implicit in all our practical commitments

and priorities. The question of what we ought to do with our time — a question

that is at issue in everything we do — presupposes that we understand our time

to be finite.

Hence,

mortality is the condition of agency and freedom. To be free is not to be

sovereign or liberated from all constraints. Rather, we are free because we are

able to ask ourselves what we ought to do with our time. All forms of freedom —

the freedom to act, to speak, to love — are intelligible as freedom only

insofar as we are free to engage the question of what we should do with our

time. If it were given what we should do, what we should say, and whom we

should love — in short: if it were given what we should do with our time — we

would not be free.

The

ability to ask the question of what we ought to do with our time is the basic

condition for what I call spiritual freedom. To lead a free, spiritual life

(rather than a life determined merely by natural instincts), I must be

responsible for what I do. This is not to say that I am free from natural and

social constraints. I did not choose to be born with the limitations and

abilities I happen to have. Moreover, I had no control over who took care of

me; what they did to me and for me. My family — and the larger historical

context into which I was born — shaped me before I could do anything about it.

Likewise,

social norms continue to inform who I can take myself to be and what I can do

with my life. Without social norms, which I did not invent and that shape the

world in which I find myself, I can have no understanding of who to be or what

to do. Nevertheless, I am responsible for upholding, challenging or

transforming these norms. I am not merely causally determined by nature or

norms but act in light of norms that I can challenge and transform. Even at the

price of my biological survival, my material well-being or my social standing,

I can give my life for a principle to which I hold myself or for a cause in

which I believe. This is what it means to lead a spiritual life. I must always

live in relation to my irrevocable death — otherwise there would be nothing at

stake in dedicating my life to anything.

Any form

of spiritual life must therefore be animated by the anxiety of being mortal,

even in the most profound fulfillment of our aspirations. Our anxiety before

death is not reducible to a psychological condition that can or should be

overcome. Rather, anxiety is a condition of intelligibility for leading a free

life and being passionately committed. As long as our lives matter to us, we

must be animated by the anxiety that our time is finite, since otherwise there

would be no urgency in doing anything and being anyone.

Even if

your project is to lead your life without psychological anxiety before death —

for example by devoting yourself to Buddhist meditation — that project is

intelligible only because you are anxious not to waste your life on being

anxious before death. Only in light of the apprehension that we will die — that

our lifetime is indefinite but finite — can we ask ourselves what we ought to

do with our lives and put ourselves at stake in our activities. This is why all

religious visions of eternity ultimately are visions of unfreedom. In the

consummation of eternity, there would be no question of what we should do with

our lives. We would be absorbed in bliss forever and thereby deprived of any

possible agency. Rather than having a free relation to what we do and what we

love, we would be compelled by necessity to enjoy it.

In

contrast, we should recognize that we must be vulnerable — we must be marked by

the suffering of pain, the mourning of loss, the anxiety before death — in

order to lead our lives and care about one another. We can thereby acknowledge

that our life together is our ultimate purpose. What we are missing is not

eternal bliss but social and institutional forms that would enable us to lead

flourishing lives. This is why the critique of religion must be accompanied by

a critique of the existing forms of our life together. If we merely criticized

religious notions of salvation — without seeking to overcome the forms of

social injustice to which religions respond — the critique would be empty and

patronizing. The task is to transform our social conditions in such a way that

we can let go of the promise of salvation and recognize that everything depends

on what we do with our finite time together. The heart of spiritual life is not

the empty tranquillity of eternal peace but the mutual recognition of our

fragility and our freedom.

We're

all going to die. How we should spend our time before we hit our expiration

date has been a main concern of philosophers from Ancient Greece to the present

day, when most people are familiar with moral philosophy thanks to The Good

Place. The question is how we can find meaning and purpose in an existence that

can seem meaningless. The answer that Martin Hägglund, a professor of

contemporary literature at Yale, comes up with in This Life: Secular Faith and

Spiritual Freedom, is democratic socialism—which can only be achieved, he notes

in his introduction, "through a fundamental practical revaluation of the

way we lead our lives together."

"Under

capitalism," he continues, "we cannot actually negotiate the fundamental

questions of what we collectively value, since the purpose of our economy is

beyond the power of democratic deliberation."

For Hägglund,

democratic socialism and freedom go hand in hand—to have the former, we need to

rid ourselves of the constraints of capitalism. His aim, essentially, is to

have enough resources publicly owned that each of us can do what we want and

consequently advance humanity, instead of being shackled to system that

probably doesn't operate well any longer. (Or perhaps never did.)

The book is an

exploration of how we should be spending our (limited) time that ultimately

asserts, as the New Republic stated in a review, a "spiritual case for

socialism." It's an argument that connects a rejection of all forms of

religious belief to the abuses and constraints of capitalism. At the crux of

the thesis is what Hägglund labels as secular faith. "To have secular

faith," Hägglund writes, "is to be devoted to a life that will end,

to be dedicated to projects that can fail or break down."

He's most

concerned with how we structure our days and what we value, and though his book

is explicitly anti-religion, it lacks the bombast of the so-called New

Atheists. It's at once a broadly accessible and academic volume (it's set to be

the topic of conferences at Harvard, Yale, and NYU), and tackles timely

issues—climate change, the rule of the billionaire class, the Catholic Church

sexual abuse scandal, our increasing focus on work—without seeming ripped from

the headlines.

VICE

talked with Hägglund about the rise of socialism in the United States,

Americans' relation to work, critiques of religion, and how we might all

improve society going forward.

VICE:

This Life seems embedded in the times we live in without bludgeoning the reader

over the head. There isn't anything, for instance, relating to Donald Trump.

Was that intentional—writing a book that calls for a new way of living, at a

moment in our history when it seems as if our institutions, our governments,

our religions are on the brink of collapse? Or did it simply become more

"relevant"—meaning Americans were talking more and more about

socialism—after the 2016 presidential election?

Martin Hägglund: When I started working on the

book six years ago, I did not know how timely it would end up being (I was even

advised against speaking of "democratic socialism" at the time, since

people thought it would be off-putting to most readers). From the beginning,

though, I knew I wanted to respond to our historical epoch, in which social

inequality, climate change, and global injustice are intertwined with the

resurgence of religious forms of authority that deny the ultimate importance of

these matters. My way of responding was to write a book that addresses

fundamental philosophical questions of life and death, but also offers a new

political vision.

V : One effect of our historical moment is

that the idea of socialism is now said to be "hip" among the younger

generation. How do you feel about that?

MH :

The

interesting thing with our current moment is that the fundamental questions of

how we should organize our society—of how we should live and work together—are

felt with a new urgency. I think it is an important moment, but for it to gain

substance we need much deeper analyses of what we mean by capitalism and

socialism. There is a widespread sense that capitalism is inimical to our

lives, but also a lack of orienting visions of what an alternative form of life

could be. What we are missing are not indictments of capitalism, but a profound

definition and analysis of capitalism, as well as the principles for an

economic form of life beyond capitalism (the principles of democratic

socialism). This is what I seek to provide in the book.

V : Much

of this work focuses almost exclusively on the conception of time—which is a

nice way of saying we’re all going to die one day. Did you have a moment in

your life when you accepted that? Will a majority of people ever be able to

accept finitude? I’m asking, partly, because I’m curious if you believe people

could actually embrace what you're suggesting, or if, in the end, they're too

afraid of death?

MH : Well,

first of all, I don’t think we can or should overcome our fear of death—or more

precisely, we cannot and should not overcome our anxiety before death. As long as our lives

matter to us, we must be animated by the anxiety that our time is finite, since

otherwise there would be no urgency in trying to do anything and trying to be

anyone. What I do think we should let go of are religious ideals of being

liberated from finitude—whether in Christian eternal life or Buddhist nirvana

or some other variant. Rather than try to become invulnerable, we should

recognize that vulnerability is part of the good that we seek. In my book, this

is a therapeutic argument as much as it is a philosophical one. The therapy

will not exempt you from the risks of being committed to a finite life. You

cannot bear life on your own and those on whom you depend can end up shattering

your life. These are real dangers. But they are not reasons to try to transcend

finitude altogether. They are reasons to take our mutual dependence seriously

and develop better ways of living together.

V : Would you

suggest ridding all religion from the world? What's wrong with it?

MH : It is

very important to my approach that the critique of religion is careful and

emancipatory, rather than dismissive. The practice of religious faith has often

served—and still serves for many—as a helpful communal expression of

solidarity. Likewise, religious organizations often provide services for those

who are poor and in need. Most importantly, religious discourses have often

been mobilized in concrete struggles against injustice. In principle, however,

none of these social commitments require religious faith or a religious form of

organization. A central example in my book is Martin Luther King and the civil

rights movement. By attending closely to King's political speeches and the

concrete historical practices in which he participates, I show that the faith

which animates his political activism is better understood in terms of secular

faith than in terms of the religious faith he officially espouses.

If we are

committed to abolishing poverty rather than promising salvation for the poor,

the faith we embody in practice is secular rather than religious, since we

acknowledge our life together as our ultimate purpose. This is why the critique

of religion must be accompanied by a critique of the existing forms of our life

together. If we merely criticized religious notions of salvation—without

seeking to overcome the forms of social injustice to which religions

respond—the critique would be empty and patronizing. The task is to transform

our social conditions in such a way that we can let go of the promise of

salvation and recognize that everything depends on what we do with our finite

time together. What we are missing is not eternal bliss but social and institutional

forms that would enable us to lead flourishing lives.

V : You

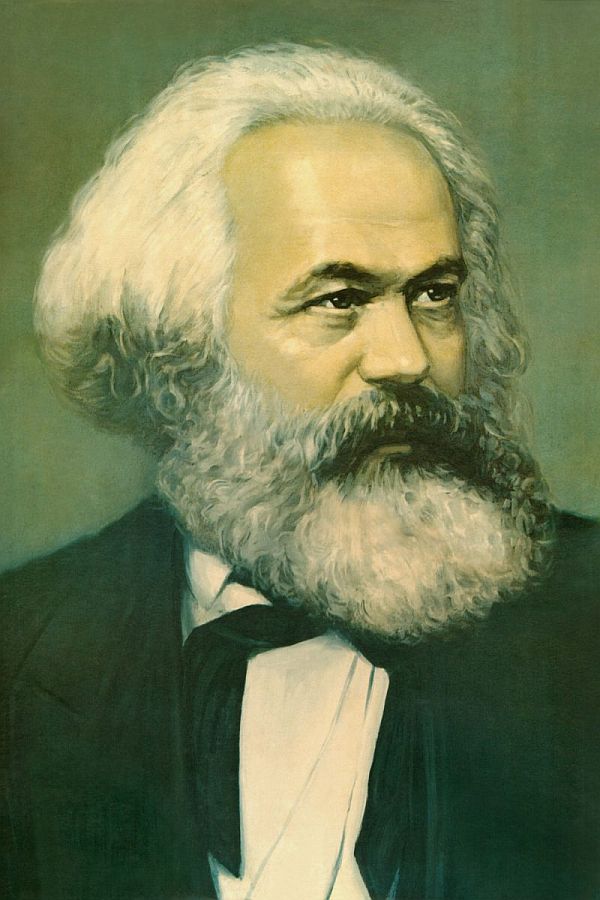

mention that Karl Marx had "no nostalgia for the premodern world"—do

you believe we're alive right now with little sense that we can form our own

history, and don’t have to be subject to it?

MH : The

reason Marx had no nostalgia for the premodern world is that he was committed

to making the modern idea of freedom a

living reality—to fulfill the promise that each one of us ought to be able to

lead a free life. In recent decades, the appeal to freedom has been

appropriated for agendas on the political right, where the idea of freedom

serves to defend "the free market" and is largely reduced to a formal

conception of individual liberty. In response, many thinkers on the political

left have retreated from or even explicitly rejected the idea of freedom. This

is a fatal mistake. Any emancipatory politics—as well as any critique of

capitalism—requires a conception of freedom. We need to rehabilitate a sense

that we are forming our own history and that we can form it in a different way.

To live a free life, it is not enough that we have the liberal rights to freedom. We must have access to the

material as well as the pedagogical and institutional resources that allow us

to pursue our freedom as an end in itself. To this end, I outline a new vision

of democratic socialism that is committed to providing the conditions for each

one of us to lead a free life, in mutual recognition of our dependence on one

another.

This

Philosopher Says We Should Replace Religion with Socialism. By Alex Norcia . Vice , March 22, 2019.

What gets a

wolf or a pigeon up in the morning? No offense to wolves or to pigeons, but

it's probably not the desire to make the world a better place. As far as we

know, humans are unique in the freedom to decide what's worth doing with our

finite time on Earth.

But as my guest

today argues, we often steal that freedom from one another or sell it off

without even realizing it—our finite lifetime, the one thing we have of real

value, is devalued by capitalism and for those who have it, by religious faith

in eternal life, or eternal everythingness, or eternal nothingness. . . .

What

happens to freedom when time is money – with Martin Hägglund. Jason Gots talks with philosopher Martin

Hägglund about his book This Life:

Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom. Martin Hägglund is a professor of

Comparative Literature and Humanities at Yale and a Guggenheim Fellowship

recipient.

Big Think

, March 9, 2019.

Any

human identity is made up in part of beliefs about how to live—what is

admirable, worthwhile, shameful, precious. These are not abstract opinions, but

are better understood as parts of who we are, distinctions that guide us

through the world as surely as a sense of up and down or near and far. And they

are full of consequences. We decide every hour which chances are worth taking,

which attachments worth making, which tedious tasks are worth the reward. The

questions add up: What shall I do with this hour, this morning, and with what

they amount to, my one life? What shall we do together?

Making

our choices count is, however, far from straightforward, and this is the

subject of Martin Hägglund’s book This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual

Freedom. Hägglund, who teaches literature at Yale, aims to give fresh

philosophical and political vitality to a longstanding question. He argues that

to live well requires two things: We need to face our choices with clarity, and

we need the power to make choices that matter. He makes a forceful case that

religion keeps believers from confronting their responsibility for the meaning

of their own lives, by displacing ultimate questions to a higher plane.

Meanwhile, capitalism denies us the power to make important choices, since we

are each to varying degrees compelled to spend our time on things that we do

not choose and that don’t carry meaning for us.

Ranging

from discussions of the nature of eternity to arguments about who should

control the means of production, Hägglund puts forward a single, sustained

picture of the situation we all face. To free ourselves spiritually, he

proposes that we adopt what he calls “secular faith”: a commitment to our

finite lives and fragile loves as the sole site of what matters, the setting

for all the stakes of existence. Achieving material freedom is a more

logistically complex project. The only social order compatible with spiritual

freedom, Hägglund believes, is democratic socialism. Only when return on

investment ceases to be the measure of value can the polity decide for itself

what counts as valuable, what kind of activity should be rewarded and

cultivated.

For a work that aims

to outdo everyone from preachers and self-helpers to political pundits and

economists, This Life spends little time orienting itself to 2019. There are no

assertions about internet tribalism, resurgent populism, or the spiritual void

of modernity; there isn’t even a Trump cameo. Yet much in the book will

resonate with a democratic left that has gained strength in the seven-plus

years since Occupy—in Black Lives Matter and the Sanders campaign, in the

vision of the Green New Deal, in the Fight for $15 and in North Carolina’s

Moral Mondays. This Life attempts to deepen the philosophical dimension of this

left and to anchor its commitments in a larger inquiry: What kind of political

and economic order can do justice to our mortality, to the fact that our lives

are all we have?

This Life is anti-religious

from stem to stern. Its strategy, however, is not to show that theism is

unscientific, as the “new atheists” have tended to do. Nor does it remind

readers of all the atrocities committed under the banner of religion, as

Christopher Hitchens did in God Is Not Great. Instead, Hägglund follows a

humanistic tradition that sees ideas of God or gods as displaced expressions of

thwarted human wishes. The notion of a kingdom of God, of divine grace, of

seeing each other face to face instead of through a glass darkly—all are ways

of trying to express what people could be to one another. Hägglund doesn’t

discard the religious impulse so much as try to separate the desire for meaning

and community from doctrine and metaphysics.

In making his target

“religion,” Hägglund takes aim at any system of thought that finds the answer

to human suffering outside this world, whether in the philosophical

indifference of Buddhist nirvana or in the eternal life of Christian heaven. As

different as these are, they each represent attempts to locate the real stakes

of existence elsewhere, safe from a reality where we love people who will

sicken and die, devote ourselves to work that will fail or be ignored, and

identify with institutions and countries that grow corrupt and do terrible

harm.

Hägglund sets out to

show that this is a kind of bad faith, a failure to reckon clearly and honestly

with our predicament. Our experience of caring for people we will lose and

projects that will fail or fade is what makes us human. If we got to heaven or

nirvana, we would no longer be persons in any sense that we could recognize, no

matter whether we imagine those ideal places through folk images of an eternal

family reunion or through high-theological concepts of timeless unity with God.

Although the dream of becoming bodhisattvas or angels expresses a very human

wish to cease our suffering and loss, if we understood it more clearly we would

see that it is also a wish to dissolve our humanity.

Hägglund

wants to turn readers back to a brief lifetime of perilous caring. “Whether I

hold something to be of small, great, or inestimable value, I must be committed

to caring for it in some form.” This, he judges,

is a

question of devoting my own lifetime to what I value. To value something, I

have to be prepared to give it at least a fraction of my time.… Finite lifetime

is the originary measure of value. The more I value something, the more of my

lifetime I am willing to spend on it.

Hägglund gives a few examples of

what this means for him. The most vital of these is his choice to spend time

writing a book—a commitment of several years for an author who believes time is

the most precious thing, and whose political project might well be crushed by resistance

or snuffed out by indifference.

In

identifying time with value, This Life can at times sound strangely like an

economics textbook. For a neoclassical economist, any choice to spend—money,

effort, attention—comes with “opportunity costs,” the paths not taken. Thus a

person’s choices comprise a pattern of trade-offs: time spent earning wages

versus time with family, the prospects of law school versus the sense of

purpose in nursing work, keeping a dangerous job rather than risk unemployment.

Modern economics assumes that prices reflect these priorities, pinpointing in

dollars and cents how much of X someone will give up in order to have Y.

Superficially at least, economic reasoning, the elite common sense of our time,

is as much concerned with the stakes of our choices as This Life is.

Hägglund

doesn’t entirely discard this reasoning. Instead he deepens it. To take free

choice seriously, he argues, we need a conception of freedom that is not tied

to selling our time and talents at the market rate just to go on living. We are

in “the realm of freedom,” writes Hägglund, when we can act in keeping with our

values. By contrast, we are in the “realm of necessity” when we adopt an alien

set of priorities just to get by. A great many of the choices most people face

under capitalism fall within the realm of necessity. How do you make a living

in an economy that rewards predatory lending over teaching and nursing? Or how

do you present yourself in a workplace that rewards competition and often

embarrassing self-promotion?

Economic

thought treats these choices as if they were just as “free” as Bill Gates’s

next decision to channel his philanthropic spending to this group or that.

Hägglund sees it differently: Our economy keeps its participants locked in the

realm of necessity for much of their lives, draining away their time in unfree

activity. In the realm of necessity there is very little opportunity to spend

our lives on the things we care for, to devote ourselves to what we think most

worthwhile. Economic life may be a tapestry of choices, but as long as it

directs its participants toward goals they do not believe truly worthwhile, a

life of such choice is a grotesque of freedom.

Hägglund

formulates his criticisms of this system by taking liberal values more

seriously than many liberals do. He shares the liberal conviction that people

have to determine the meaning of their lives by individual reckoning. But he

contends that a liberal who fully understood the meaning of this commitment

would become a socialist. This is because the market economy dictates answers

to the most important question—what is our time worth? To be free is to be able

to give your own answer to this question; but in our lives, the answer comes to

us in the form of wages and such potent monstrosities as the rate of return on

investment in our human capital. These dollar-and-cent measures make decisions

for a boss or owner as for a worker: Mind the bottom line, or “market

discipline” will replace you with someone who will.

The

market presses some people closer to the bone than others, but it drives

everyone, because it is a system for determining the price of things, among

them time itself, and substituting that price for any competing valuation. You

cannot exempt yourself, except in the rare case where you have “won” enough or

inherited enough—and even then you are the exception, an odd rich person with

economic power over others’ time, not one in a society of free equals.

Instead

of occasional exceptions, we need collective self-emancipation into a different

regime of value. Hägglund defines his ideal—democratic socialism—as a system of

public ownership of productive resources in an economy that aims at maximizing

“socially available free time,” that is, making the realm of freedom as large

and inclusive as possible. His democratic socialist society would create

institutions that let us learn without incurring insurmountable debt, and work

without fearing poverty or untreated illness. It would not make its members

trade their time for mere survival. He invokes Marx’s “from each according to

his ability, to each according to his needs.”

Hägglund

can give the impression of gliding over the problems this society might face.

There is always some work that not all that many people really want to do,

unwelcome but socially necessary labor. There is no way around emptying

bedpans, caring for the severely demented, sorting recycled goods, providing

day care for other people’s children, picking lettuce, cleaning up after concerts,

and so forth. Hägglund writes that under democratic socialism “we will be

intrinsically motivated to participate in social labor when we can recognize

that the social production is for the sake of the common good and our own

freedom to lead a life,” making such labor “inherently free.” Yet it is hard to

imagine the voluntary caretaking of others’ needs that sometimes happens in

families and religious communities scaling up to the national or global level

solely “through education and democratic deliberation.”

Readers

who have these doubts, Hägglund writes, “should consider their lack of faith in

our spiritual freedom.” It is an important response, if not a decisive one. The

certified best minds of their times have believed democracy a recipe for

anarchy, women’s equality a monstrosity, and so forth. Every age invents

respectable formulas to convert local limits of imagination and experience into

universal limits on reality. A book that presses against these limits does more

service than one that dresses them up with libertarian bromides and a little

evolutionary psychology, as too many of our “big thinkers” do. Hägglund’s

question is not which marginal tax rate would be compatible with incentivizing

effort in 2019. It is how to think about the basic ordering of the world. To

the extent that readers find his argument persuasive, it is up to them to make

it useful.

Can a religious

person who believes the ultimate stakes of existence are cosmically elsewhere

also invest this life with the moral urgency that it merits? Hägglund argues

vigorously that they cannot. But in practice the world is full of activists who

are religious and who seem to square the circle in their own lives. Many of

them say that their sense of the goodness and moral weight of this life, and

their motive to uphold and transform it, arise from experiencing the world as

infused with divine love, as a creation. For my part, I would not have taken

this observation so seriously before I spent nearly 15 years living in the

South among activist friends and movement leaders whose work is entirely

stitched into religious community, language, and feeling.

Whether or not

Hägglund needs to save devotion from religion, This Life presents a vital

alternative to certain kinds of nihilism that today’s politics can produce—when

the news brings weekly updates of dire climate forecasts and America seethes

under Trumpism. It is now almost ordinary to remark in casual conversation that

things are pretty much over, that we are just waiting for the catastrophes and

the resource wars to begin in earnest. In a decade or three, when we watch the

floods at the coasts, the inland droughts, and the waves of refugees breaking

on the border walls of Europe and the United States—or even shattering the

walls—we will at least have seen it coming. There is a weird satisfaction in

being among the ones who saw that capitalism is at once too venal and too

powerful, or humanity at large too shortsighted and tribal to survive.

Nihilism has minor

chords as well as major ones. It might be that, with so much disaster so

thoroughly forecast, you will judge that the only thing to do is to draw up the

bridges and look out for your own: spend college angling for a hedge-fund job,

or stockpile rifles and ammunition, and hope that, whether with a MacBook Pro

or a six-shooter, your grandchildren will be among the lucky few who can defend

a secure spot in New Zealand or Montana. If you aren’t heroically inclined, you

may simply look out for your own without hatching much of a plan for their

future.

If you feel the pull

of this kind of thinking, Hägglund wants to persuade you that this is bad

faith. We are creatures who care, whose nature is to grow infinitely attached

to finite things. What we truly believe is worth our time, the natural things

and the cultural forms in which we find the richness of this life, gives us an

imperative to take responsibility for them.

This

book might be, in other words, not so much about why to be an atheist as

how—how to embrace emotionally hazardous forms of existential commitment as

weighty as religious devotion, and without the nominal assurances of religion.

It is also perhaps less about why to be on the left than about how. I am not

sure that anyone who has signed on contentedly for growing inequality mitigated

by a little redistribution will be moved to democratic socialism by Hägglund’s

conception of freedom. But for those who start with some version of his

politics, the idea that we should be fighting for control over our time might

prove powerful. What does “free college” or “Medicare for all” come down to,

other than saying that our lives should be our own to use well, not parceled

out in years of debt service and cramped by fear of future medical bills? What

is the Green New Deal but an explicit engagement with the value of life, an

effort to secure a humane future in a world where we do not live by exploiting

one another?

The old

labor slogan—eight hours for work, eight for rest, and eight for what we

will—sticks around because control over our time really is the beginning of all

other forms of autonomy. To understand our lives this way can illuminate rather

abstract considerations, tying them to the most immediate, felt concerns of a

finite life. What are we fighting for? For more of the only thing we will ever

have, the time of our lives. Why do we fight for it? Because it goes so fast,

and, for a human being who faces the tragedy of our situation, there can, and

should, never be enough of this life.

What gets a

wolf or a pigeon up in the morning? No offense to wolves or to pigeons, but

it's probably not the desire to make the world a better place. As far as we

know, humans are unique in the freedom to decide what's worth doing with our

finite time on Earth.

The Spiritual

Case for Socialism. By Jedediah Britton-Purdy. The New Republic , February 19, 2019.

In a new

book, philosopher Martin Hägglund argues that only atheists are truly committed

to improving our world. But people of faith and socialists have more in common

than he thinks

Religious

zealots are no longer the only ones to prophesy the apocalypse. Secular

scientists and experts regularly warn us that the skies will fall, that plagues

will overwhelm us, and that the seas will cover our cities—all of it

well-deserved punishment for our sins. We live in an era in which traditionally

sacred questions about the nature and end of our world have become political.

The old firewall between faith and politics, so lovingly crafted in the

eighteenth century to solve problems that are no longer ours, will likely come

down whether we like it or not.

Martin

Hägglund, a philosopher and literary critic at Yale, has published a book for

this moment. This Life is an audacious, ambitious, and often maddening tour de

force that argues that major existential questions—about the world and our

place in it—must once again inflame our politics. What’s more, he presumes to

answer those questions, providing an ambitious defense of secularism and a

provocative attempt to link a secular worldview with a robust politics. To

fully abandon God, Hägglund proposes, is to become a democratic socialist.

Few have

tried harder than Hägglund to consider secularism’s political and ethical

consequences. In a world in which Friedrich Nietzsche and Ayn Rand seem to have

a stranglehold on the theme, this is a crucially important case to make, and to

a crucially important audience. In the United States, and globally too, the

number of religiously unaffiliated people grows by the year. This Life asks

secular readers to take their own secularism seriously, reminding them that

their worldview can and ought to influence their politics as fully as it might

for religious believers. He is not, to be clear, making an empirical claim that

secularists are, in fact, the light of the world, but rather a normative

argument that, if they understand themselves correctly, they should be. This

aspect of Hägglund’s book is convincing, even if his kindred attempt to

convince the religious among us to actually become secularists is less

successful. Regardless, his project is to be applauded. Its iconoclasm and

sweep provide an example of what intellectual activity can and should look like

in an era of emergency.

This

Life opens with an attack on religion, but of a novel sort. Hägglund is not

much interested in whether or not God exists. He prefers to root out the more

persistent belief that it would be a good thing if God existed. In his view,

even many secular people are nostalgic for faith, and mourn the absence of a

deity to command us and save us. This has kept the secular amongst us from

deeply thinking through what it means to be secular—what it means, in other

words, to accept that the lives we have here are the only ones we will ever

have.

In

Hägglund’s view, the essence of religion is a flight from finitude. He sees all

religions as being basically the same in this regard, in that they all counsel

us that the empirical world is essentially unreal. Our salvation, after all,

resides in heaven or some kind of afterlife. Given that, the religious believer

has no incentive to grant any independent significance to a particular human

being, or even to the natural world. In his reading of Augustine, C. S. Lewis,

Søren Kierkegaard, and other religious writers, he argues that they are

intellectually committed to a devaluation of our shared, finite life. At the

same time, he delights in offering evidence that these religious

thinkers—despite themselves, in his view—granted meaning and significance to

the finite world and its denizens.

His

purpose is not merely to root out perceived hypocrisy, but to buttress the

claim that devotion to the finite, or what he calls “secular faith,” is

intrinsic to what we are as human beings. This anthropology is taken up in the

second half of the book, which is devoted to what he calls “spiritual freedom.”

In these chapters, Hägglund asks some basic questions: What would be the

political and social consequences of true atheism? If we truly are alone in the

world, what would it mean for us? These only seem banal because so few writers

have the audacity to pose them so baldly.

The

answers certainly are not banal: starting from first principles, Hägglund seeks

to reconstruct what a worthwhile human life might look like, and what

institutional arrangement might make it possible. The most interesting feature

of his analysis is the great attention he gives to temporality. It is not just

that human beings are “rational animals,” as Aristotle put it, but that our

rationality expresses itself first and foremost through our decisions about how

to use our time (hence the importance of finitude as a category). This is less

an ethical principle than a meta-ethical one. We can debate endlessly over

whether we should devote ourselves to art, or love, or political organizing.

Hägglund simply wants us to see that these debates hinge on how to spend our

time.

Time,

not carbon or land, is the raw material of our humanity. With this insight in

hand, Hägglund turns his attention to the state of our shared world now—one

that is organized around literally inhuman premises. If our freedom is defined

by the rational use of our time, capitalism is defined by its irrational waste.

In an era of what David Graeber calls “bullshit jobs” and increasing awareness

of the crushing requirements of modern labor, there is something plausible

about this as a sociological observation. Hägglund presents it as a theoretical

insight, too. In all of the excitement over the revival of socialism, it can be

easy to lose sight of what capitalism actually consists in—or at least, how

Marx understood it. Hägglund reminds us that Marx understood capitalism

primarily through temporal categories. The historical significance of wage

labor, after all, was precisely its linkage between monetary remuneration and

the iron progress of the clock.

This

linkage between value and labor-time, codified into the wage, distinguishes

capitalism from alternative economic forms. It explains why the explosive

technological innovations of the modern era, celebrated by Marx and Hägglund

alike, have not shortened our labor time appreciably. And it explains why

unemployment is immediately classified as a problem, instead of celebrated as

evidence that we can feed and clothe ourselves with less labor than before.

In

short, Hägglund believes that we are defined by the way that we spend our time,

but that we are enmeshed in a system that devours our time without our rational

input. The only solution, therefore, would be to remake our economic system in

a way that honors our finite time precisely by disaggregating the equation of

time and economic value that is the hallmark of capitalism.

The book

concludes with a robust vision of democratic socialism in which time, and not

just capital, serves as a resource to be cherished and distributed. Hägglund is

not opposed to the welfarist measures that constitute the horizon of democratic

politics today. He does, though, think that they are inadequate given the

magnitude of our crisis; they do not arise from a fully articulated philosophy

of what man is, and what sort of world would be fit for her flourishing. More

pointedly, he thinks that we are focusing too much on the mechanisms of

redistribution, and not enough on the capitalist, temporal logic that governs

the creation of value.

His form

of democratic socialism essentially gives us back our time. The endless hours

that are sucked into the maw of production can be ours, once again, if we have

the courage to claim them. Partially, this involves the simple exploitation of

technology to increase the amount of time we are away from work. It also,

though, presumes the revaluation of work and the economy itself. He imagines a

world in which our work is unalienated because we have freely chosen it, and

because we understand how it contributes to a just world that we want to be our

own. This is a world, too, in which we are not riveted to a profession forever,

but can exercise our talents in diverse ways across our lives because we are

not submitting our bodies to the dictates of the market.

This is

a utopian vision, to be sure. Hägglund does not do the work to show how it

might plausibly be on the horizon, or ask how it might be possible in a

globalized economy where the most unsavory and dangerous sorts of labor are

often outsourced. That, though, is the great virtue of the book: it provides a

regulative ideal, and a reminder of what kind of world we are actually fighting

for. However secular he might be, Hägglund’s is ultimately a project of

restoring faith. And if the history of religion teaches anything, it is that

faith is not created with concrete proposals. We have faith in a story, and in

a promise, and this is what Hägglund seeks to restore to his secular audience.

If I

have tried to depict This Life as an example of what we might call “good”

utopianism, there is an element of misguided utopianism in the book, too. This

becomes apparent in his treatment of religion. However bracing and convincing

his linkage between secularism and socialism might be, he fails to make the

case, either normatively or empirically, that only secularism can save us.

For all

of its laudable concern for democracy, there is something imperious in

Hägglund’s dismissal of religious believers: specifically, his contention that,

insofar as they are properly religious, they do not and cannot have any concern

for the finite world. It is enormously provocative and counterintuitive to

assert that religious traditions (all of them!) counsel believers to ignore

finite beings in pursuit of eternal happiness. And yet this is his consistent

claim. “If you truly believed in the existence of eternity,” he argues, “there

would be no reason to mourn the loss of a finite life.”

The most

obvious objection to Hägglund’s thesis is simply that religious people care

about the world, and other people, all of the time. Indeed, the history of

humanity is little else than the history of that care. His response is that

when they do so, they are not in fact acting religiously but are, despite their

own self-perception, honoring the secular faith that is at the heart of the

human condition. This sweeping argument is made largely through an analysis of

Kierkegaard’s philosophy, designed to show that his theological vision does not

in fact make room for a devotion to finite beings. A textual analysis of a

famously complex thinker simply cannot bear this much weight. Even if we assume

that Kierkegaard can stand in for the entire Christian tradition, which is a

stretch, he simply cannot stand in for “religion” as a whole (represented in

this book, it must be said, almost entirely by European and Christian men).

So even if Hägglund is right about Kierkegaard,

there is no reason to conclude that it would be relevant to, say, the millions

of Muslim mothers who care deeply about their children. Religious believers

claim, in all manner of ways, that their care for the finite world is enlivened

and awakened by their sense that the world is not dead matter, but rather

emanates from the divine. Hägglund considers this to be impossible, but he does

not directly explain why. Even secular people can imagine some form of it.

Imagine that a dear friend died and left their beloved dog in your care, and

that for years you loved and cared for this dog. It is likely that you would

love this dog both in its own right, and also because of its provenance:

through caring for the dog, you are honoring both the dog and the friend who

gave it to you, even though that friend no longer exists. It would be both

uncharitable and mistaken for someone to tell you that you did not really love

the dog, but were only honoring your friend. It would be especially so if that

person did not know you but only knew the broad outlines of your story. And yet

this is precisely Hägglund’s position. He believes that you can

either

love the world in its finitude, or you can love the eternal creator, but you

cannot possibly do both, and one could not possibly enrich the other.

“This

Life,” to which Hägglund is so admirably committed, is teeming with cases in

which love for God and love for the finite world enhance one another. For many,

this world matters precisely because of its linkage to the eternal.

Consider

care for the environment, which Hägglund rightly emphasizes as a crucial issue

for our times. His view is that religious believers, insofar as they are

consistent, should be indifferent to the fate of the world because they care

only about the afterlife. One objection is that this argument, which uses

clearly Christian categories, fails to address the Native American traditions

that have been employed against oil companies in recent years, most famously at

Standing Rock. Another would be that, even from within the Christian tradition,

there are deep resources for ecological consciousness that cannot be dismissed

out of hand. The theologian Brett Grainger, for instance, introduces us to some

in Church in the Wild: Evangelicals in Antebellum America. While we sometimes

attribute an enlightened ecology to the New England Puritans, he shows how the

many millions of evangelicals of the same period had a similar sensibility. The

book shows what an approach to religion that strays from the titanic

intellectuals and texts can do. In lieu of a rereading of Thoreau, Grainger

offers us a fine-grained account of the hymns, sermons, and poetry that

constituted the commonsense worldview of a people.

It is no

secret that evangelicals sought to study scripture and nature—or what they

called God’s two books—in tandem. What Grainger shows is how deeply this

permeated their daily lives. These were people who worshipped outdoors, and who

viewed the contemplation of nature as a central component of spiritual

practice. This reached bizarre heights in the evangelical attitude to health.

They were, Grainger reveals, quite committed to hydrotherapy, believing that

water, the stuff of baptism, had unique healing properties, and that mineral

springs in particular were sacred sites. His point is that the evangelical

tradition has enormous resources for a veneration of nature and that, moreover,

the history of U.S. environmentalism relies on a hidden Protestant heritage.

Hägglund

does not, and cannot, convincingly show that none of these traditions can

nourish a genuine commitment to the finite world. The problem is that, for a

book so concerned with theology, Hägglund does not really have a theory of religion.

He does not, in other words, have a theory to explain why so many people, today

and historically, have devoted themselves to (what he sees as) transparently

false understandings of the universe. Ironically, Marx himself is more

instructive on this point, and less committed to a reductive reading of

religious activity. His fullest analysis of the topic (“On the Jewish

Question”) was in fact written to refute a philosopher named Bruno Bauer who

had made a claim similar to Hägglund’s. Marx did not believe that religion was

an error in judgment, but rather an unsurprising response to a world in which

our political and ethical ideals are so hideously absent from our economic

realities. The mystifications of religion, in other words, are a reflection of the

mystifications and contradictions of capitalism, and faith a coherent response

to a world where salvation seems impossible.

Marx had

no particular sympathy for religion, but he did not seek to explain it away as

a failure of courage or as an error in judgment. Insofar as he does so,

Hägglund denies himself the ability to empathize with the billions for whom

faith might be the only recourse in a world of savagery—“the heart,” as Marx

put it, “of a heartless world.” That insight did not commit Marx to providing a

place for religion in the communist utopia to come, but it did allow him to

better understand its role in the fallen world we call home.

The

world cannot be saved by one book, even one as ambitious as This Life. That

would be the most religious claim of all, and one that Hägglund would certainly

not endorse. We need many books, like this, speaking to many audiences, if we

are to face the crisis of our moment. Hägglund’s is a book for a secular

audience, but it is not one that can summon a secular public.

Democratic

socialism will run into the ground if it lashes itself as tightly as this to a

rigorous secularism. About 80 percent of the world’s population formally

subscribes to some form of religious belief, meaning that the concepts and

categories that they have at hand to understand political, economic, and

climactic affairs are at least inflected by religious categories and

institutions. If the transition away from rapacious capitalism must begin with

an educational process to reduce that number to zero, we will still be holding

seminars on Kierkegaard until the seas overwhelm us.

The task

for the present cannot be to convince the world’s population to abandon

religion, and then to convince them that secularism entails democratic

socialism. The task, now, is to meet people where they are, and to understand

the stories and institutions that structure their lives in order to see how the

moral arc of their particular universe might be bent toward justice.

To do that, though, we need a vision of justice that

is plausible and compelling enough to organize our efforts. Hägglund’s book

provides one. After a half century of anti-utopian suspicion, This Life calls us back to a

nearly forgotten style of thinking and imagining. In our time of genetic

experimentation and climate apocalypse, we are forced to confront anew, and in

public, the questions that long seemed safely sequestered in our private lives,

and our private hearts: What is it to be human? What do we owe one another?

What is to be done? As the waters rise, these questions could not be more

urgent. It is impossible to believe that we will all arrive at the same

answers. But unless we all start asking them, and with a real commitment to

continued life on earth, we are doomed. Hägglund is right that time is our most

precious resource. Unlike

carbon, though, there is not much left.

Democracy

Without God. By James G. Chappel. Boston Review , March 4, 2019

No comments:

Post a Comment