Man of

letters and drummer (The Fall, House Of All) Paul Hanley has written a book on

Buzzcocks called Sixteen Again. A limited edition hardback is available from

publishers Route now and a paperback will be available in April 2024.

Sixteen

Again: How Pete Shelley & Buzzcocks Changed Manchester Music (And Me), to

give it its full title, mixes together biography, interview, critique and

social history to create a full picture of the legendary Manchester group,

equally beloved of fans of punk, post punk and indie.

Route – who

have also published Hanley's Leave The Capital: A History Of Manchester Music

In 13 Recordings and the masterful Have A Bleedin Guess: The Story Of Hex

Enduction Hour – have the following to say: "Paul Hanley's obsession with

Buzzcocks peaked between the ages of 14 and 16, exactly the age when ‘favourite

band’ actually means something important. An essential part of the charm of

Buzzcocks to him were their proximity and approachability."

Taking a

break from his current duties as one half of the drumming duo who power recent

tQ Album Of The Year folk, House Of All, and co-host of the Oh! Brother podcast

with kin Steve Hanley, Paul submitted to some quick fire questions about the

book, Buzzcocks and OBOGFRS (other bits of general Fall-related stuff).

What really

went on there? We only have this excerpt:

Why did you

choose Buzzcocks?

Paul

Hanley: Well, there’s the cultural significance of them bringing the Sex

Pistols to Manchester twice, and kick starting indie music. Then there is the

fact that Pete Shelley was a song writing genius who could say more in a three

minute pop song than most writers could say in a whole album. But most

importantly they were my favourite band between the ages of 14 and 16, which is

about the only time in your life when it’s OK to have a favourite band.

What do you

think of the Tony McGartland book, Buzzcocks: The Complete History and Pete and

Louis Shelley's Ever Fallen In Love: The Lost Buzzcocks Tapes? I think they are

the only other Buzzcocks books right?

PH: Yes,

apart from Steve Diggle’s book [The Buzzcocks: Harmony In My Head]. I used all

three in writing this, unsurprisingly. But there is a definite lack of books

about Pete Shelley and Buzzcocks, certainly compared to The Clash and the Sex

Pistols, which seems criminal to me. Hopefully this book is different from all

the others. I wanted to combine telling the story with getting across just how

much Buzzcocks meant to me

Did you

perceive of some misconceptions about the band you were keen to tackle?

PH: Yes.

There’s this slightly snide dismissal of Pete’s songs as ‘just love songs’

which they’re definitely not.

In that

sense is their closest comparison The Undertones? Or can they be compared to

anyone else?

PH: There’s

definitely a lineage between Buzzcocks and The Undertones in their ability to

convey the thrills and spills of youthful yearning over driving melody. I think

The Undertones would happily acknowledge an influence. But Undertones aside I

think a lot of bands influenced by Buzzcocks kind of missed the point.

Care to

elaborate?

PH: Ok.

Specifically, bands like Green Day. There’s a big difference between speaking

to youth and just being childish.

Do you

cover Shelley's solo albums?

PH: Yes.

Not in as much detail but Pete’s journey away from Buzzcocks’ sound and then

how he got back to it is fascinating.

Did you get

to interview everyone you wanted for the book?

PH: Yes

pretty much. I deliberately chose not to speak to Steve Diggle as I wanted to

avoid getting too close and have it affect the story I wanted to tell. And I

couldn’t speak to Pete obviously so it wouldn’t have been fair! I think the

story of the Buzzcocks is the story of Steve and Pete; the story of how they

maintained that relationship despite being very different characters is pretty

key I think.

Were

relations between The Fall and The Buzzcocks always cordial?

PH:

Buzzcocks and Richard Boon were very supportive of The Fall in the early days,

as they were with lots of Manchester acts. I think Mark certainly respected

Pete even if he was a bit sniffy about Buzzcocks music.

Was

Shelley's bisexuality ever a problem for the band?

PH: No I

don’t think they cared. His lyrics were always gender fluid, and his sexuality

was never part of the act, it was just who he was. He was years ahead of his

time in that respect.

What are

the unheralded songs you love that aren't on Singles Going Steady?

PH:

'Money'; 'Who’ll Help Me To Forget?'

You've

completely changed in the last few years haven't you? Three books published and

an English Literature degree completed since 2017. It's very impressive but are

your friends and family surprised by it?

PH: Well I

hope they’re not too surprised! They’ve been very supportive. The degree was a

dream. I loved it. And I really got the bug for writing. When you’re doing a

degree you always have a piece of writing on the go, so I just carried on!

How are you

enjoying The House Of All?

PH: The

gigs have been great actually. We seem to be going down very well and the

footfall is very gratifying. It’s a real shame Pete [Greenway] wasn’t able to

join us but Phil [Lewis] has done a great job.

Paul: I do

feel Irish in many ways. We were a fairly Irish household growing up. But I

feel far more Dublinian – if that’s a word – than just generally Irish, in the

same way I feel Mancunian rather than English. I think he was about a year old.

Sixteen

Again: How Pete Shelley & Buzzcocks Changed Manchester Music (And Me) is

available to buy from Route now

The Fall's

Paul Hanley On Buzzcocks Book. By Francisco Scaramanga. The Quietus, December 18, 2023.

Route TV, November 18, 2023.

Gelesen: 27. –

28.12.2023 (netto 267 Seiten, in Englisch – wird wohl ehr nicht auf Deutsch

erscheinen)

#bookcollectorsarepreteniousarseholes

– Ich habe mir für einen ordentlichen Batzen Geld eine “Advance Edition”

geleistet: Signed, limited und vor dem Erscheinen im April 2024 pünktlich zu

Weihnachten hier. Mit einem collen Badge (in alter Buzzcocks Tradition).

Post-Brexit Porto und Zoll sind mehr als der Buchpreis, Danke Merkel!

2021 ist ja

bereits ein Buch über Pete erschienen, daneben hatte Steve Diggle bereits 2002

eine “Biographie” von einem Journalisten schreiben lassen (die habe ich damals

nach kurzem Querlesen nicht gekauft). Ansonsten gibt es kaum etwas, ehr als

Abfallprodukt der Arbeiten von Malcolm Garrett, der mit seinen Designs für die

Buzzcocks ja Plattencover, Poster und Badges für die Ewigkeit erschaffen hat.

Paul Hanley, der

Autor, ist sowohl Fan als auch Kenner der Musik-Szene Nordenglands, er spielte

1980 bis 1985 bei The Fall. Und er schreibt dieses Buch aus der Sicht eines

informierten Fans…

Und weil es aus der Fan Perspektive geschrieben ist fußt es aus O-Tönen, die er aus allen möglichen Quellen zusammengetragen hat (87 insgesamt, alle im Anhang verzeichnet). Und dabei zeichnet er ein ziemlich realistisches Bild einer Band, die früh dabei war (1976) und wie viele andere ebenso früh fertig war (mit sich, mit der Musik).

Spannende

Fußnote: Fertig waren sie in der Markthalle, Hamburg, 23.01.1981. Danach war

Schicht im Schacht – erstmal. Und Steve Diggle und Pete Shelley hatten sich

erstmal 8 Jahre nix zu sagen.

Durch den Mix aus O-Tönen und dem kundigen Kommentar bzw. der persönlichen Einordnung ließt sich das Buch extrem gut, ich habe es mehr oder weniger verschlungen. Auch weil ich Fan geblieben bin.

Da Hanley selber

Musiker ist (auch wenn er bei einer weniger Ohrenschmeichelnden Band) kann er

das musikalische auch richtig verorten. Downstrokes galore!

Was er aber auch offen und ehrlich rüberbringt ist, wie die Band im Grunde verglüht ist und sowohl Pete (der mit mehr elektronischer Musik zumindest ein klein wenig Erfolg hatte) als auch Steve nutzen nach den Buzzcocks das immer noch ein wenig hereinkommende Geld um Soloideen nachzugehen. Die anderen beiden (John Maher, Steve Garvey) setzten sich in ein erfolgreiches und normales Berufsleben ab.

Und ab hier wird das

Buch dann schonungslos ehrlich, die Reunion war wohl ehr dem Geld geschuldet

(aber das daraus entstandene Konstrukt von Pete/Steve plus Tony/Phil gab es

dann satte 13 Jahre und damit etliche Jahre mehr als die erste erfolgreiche

Inkarnation.

Es war am Ende

dann doch ein Beruf, bei dem es um regelmäßiges Einkommen ging. Privat wollte

man nix mit den Kollegen zu tun haben.

Das es am Ende vor allem für Steve vor allem um Ego, Einkommenund Versorgung mit Champagner ging wurde spätestens 2019 klar: Die Buzzcocks hatten eine “40 Years of Singles Going Steady” show in der Royal Albert Hall geplant – der Herzinfakt von Pete kam im Dezember 2018 dazwischen. Steve nutzte den Termin dann für ordentlich Egopolitur:

Klasse Buch:

Vergötterung wo erforderlich, Kritik wo angebracht. Mit viel detailliertem

Fachwissen (eg. Petes Liebelieder kammen immer ohne mänlichen oder weiblichen

Bezug aus, mit Absicht. Steve konnte oder wollte das nicht und durchbrach das

in einem seiner Songs für die Buzzcocks).

Soundtrack dazu:

Buzzcocks – Singles Going Steady, immer noch – was sonst?

PS: Der Buchtitel

löst natürlich wieder eine Träne – Sixteen Again war die ganz hervorragende

Buzzocks Cover-Band von Helge (RIP).

PPS: #bookcollectorsarepretentiousarseholes

#75/300 (um 2 falsch, Danke Merkel!)

Buch kann hier

bestellt werden! Der Autor hat auch einen historischen (endet 2020) Blog mit

(in eigenen Worten) Ruminations, accusations, felicitations, and that

Bücher, schnell

gelesen: 1.676. By Dirty Old Sod. Gehkacken,

December 2023.

The

conversation is usually the same. Regarding the UK, the best and most important

acts of the first wave of punk are Sex Pistols and The Clash. Of course,

everyone is entitled to their own opinion, but it seems a travesty that the

discussion regularly forgets the band who were, in my mind, the finest of the

lot, Buzzcocks.

Arguably

the most boundary-pushing act of the first wave of British punk, from their

music to setting up one of the first independent record labels, and even their

instrumental role in bringing the Sex Pistols to Manchester – a night credited

with kicking off the city’s musical boom – many aspects bolster this argument.

Without Buzzcocks, punk and broader alternative music today, would lack some

defining factors. This indicates just how important Buzzcocks were.

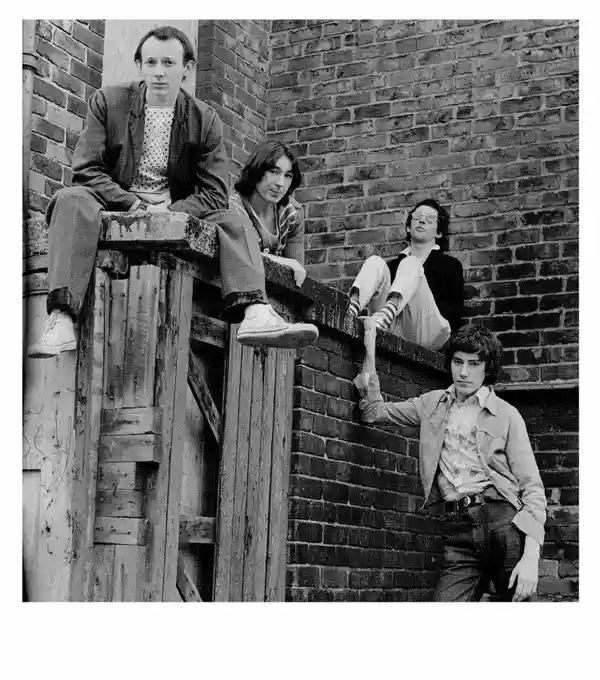

Buzzcocks

were officially formed in February 1976 by college friends Howard Devoto and

Pete Shelley. This pair travelled down to London to see the buzziest band of

the day, Sex Pistols, and organise for them to play at Manchester’s Lesser Free

Trade Hall in June 1976, one of the most consequential nights in modern British

culture. They also intended to perform at this show, but Devoto and Shelley’s

bandmates dropped out.

The band

eventually got their wishes, and after recruiting bassist Steve Diggle and

drummer John Maher, they made their debut performance opening for Sex Pistols

when they returned to Manchester for their second show in the city in July.

Things moved quickly, and Buzzcocks were now vital to a burgeoning movement. In

September 1976, the group trekked to London to perform at the two-day bonanza,

the 100 Club Punk Festival, organised by Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren.

The festival was the moment punk crystallised itself as a genuine cultural

force, with other performers including Sex Pistols, The Clash, The Damned,

Siouxsie and the Banshees, and Subway Sect.

By the end

of 1976, Buzzcocks had found their rhythm, and they recorded the four-track EP

Spiral Scratch, which arrived in January the following year. Produced by future

Factory Records alumnus Martin Hannett, it arrived on Buzzcocks’ New Hormones

label, meaning they were one of the first punk groups to establish an

independent record label, second only to The Saints and Fatal Records, created

to release ‘(I’m) Stranded’. This also saw the group insert themselves further

into the story of punk, with the song ‘Boredom’ coherently explaining the

movement’s rebellion against the man. Additionally, the band demonstrated their

genuinely artistic edge on the record, with the minimalism of the two-note solo

in ‘Boredom’ the pinnacle of this, averting the established tradition of this

guitar part. Clearly then, even at this early point in their career, Buzzcocks

had made history on numerous occasions.

Despite

these triumphs, Devoto quit the group only a few months later, citing his

displeasure at punk’s direction. He said in a statement: “I don’t like

movements. What was once unhealthily fresh is now a clean old hat”. He returned

to college for a year and then formed the widely influential post-punk outfit,

Magazine. They became one of the key players in the genre that would shine a

light on all of first-wave punk’s flaws and start to make real artistic

progress by casting aside the barriers of labels.

Devoto

leaving Buzzcocks also proved to be a significant moment for the band. It saw a

sea change occur, after which they would enter a more distinctive and essential

area, pushing the confines of punk to the absolute limit. Pete Shelley took on

the vocal duties, with his high-pitched, melodic vocals presenting a stark

contrast to the gruff delivery many punks employed due to their origins in the

blues-influenced pub rock. With Shelley taking over vocals and continuing to

play guitar, Diggle switched over to the six-string from the bass, with Garth

Davies, the original bassist rejoining. Steve Garvey eventually replaced him the

following year, a four-string hero who would give the quartet the busy

undercurrent needed for their increasingly dynamic sound.

Despite the

undoubted importance of Spiral Scratch, after Devoto left, Buzzcocks took

things up a level. Over the rest of their first chapter, which ended in 1981,

they pushed back against social and punk mores, writing music for the future

well ahead of its era. Arguably, it was more in line with what their heroes,

The Stooges and The Velvet Underground had done, with there also taboo-busting

similarities to the work of David Bowie.

When

Shelley, bandmate Steve Diggle and manager Richard Boon sat down at the British

Library in June 2016 to discuss their career, they explained how bands like The

Velvet Underground and The Stooges inspired their iconoclasm. Shelley said:

“Myself and Howard (Devoto), we were listening to… well, separately, but we had

a mutual interest, things like The Velvet Underground, The Stooges, Can, I

mean, a lot of the German… yeah Neu! I mean things that, really, when you put

on you can clear a room.”

He

continued: “In those days, it was a whole different country. It was music which

nobody liked at all. Everybody was into sort of like heavy metal, but it wasn’t

as widdly-widdly… I mean, things like Black Sabbath and Deep Purple, there was

a lot of blues, and it was all to do with how many notes you could fit into

your 20-minute guitar solo. Where, I liked the things which were more on the

noisy side, but were funny as well. So that’s basically what we tried to do… In

fact, we were making the most uncommercial form of music that we thought

possible… We even had swearing in it. Nobody did that.”

It was a

much different, more creative space to that of their most prominent punk peers,

Sex Pistols and The Clash, after Devoto left. Mainly inspired by the innovation

of The Stooges and more experimental acts such as The Velvet Underground and Can,

Shelley’s lyrics had much greater depth than almost everyone’s. A wholesale

affront to the machismo of punk, he showed it to be futile, as he discussed

personal feelings, sex and homosexuality in a wickedly comedic way, a complete

departure from the immediate moves of Sex Pistols.

Much of

this separation from the punk scene was due to Shelley. An open bisexual, his

discussions of love, sex, and other taboo issues pushed back against punk’s

standards and that of the mainstream. His lyrics set an example by sticking a

stout middle finger up to tradition and providing solace for listeners hiding

their true selves from the public. This significance cannot be overstated;

1970s Britain was a completely different time to our own. It was a much less

welcoming place for anyone who dared to veer off the beaten track.

Early

singles such as ‘Orgasm Addict’, ‘What Do I Get?’ and the iconic ‘Ever Fallen

in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve)’ remain highlights of this approach.

While the first wave of punk was mostly concerned with external issues, Shelley

was an adept songwriter who could fuse the personal with outside forces such as

the political, going far beyond that of other punk songwriters, including The

Clash’s Joe Strummer, someone credited with addressing the most important

issues of his day.

Shelley

said more in one song than many of his contemporaries managed to do in their

whole career; that’s how incisive his prose was. ‘Everybody’s Happy Nowadays’,

‘Autonomy’, ‘Lipstick’ and ‘Whatever Happened To…?’ are four more examples of

the frontman’s lyrical flair. He was afraid of no issue, and had a knack for

combining the mundane and severe, something his heroes Iggy Pop and Lou Reed

were masters at that.

Of course,

Buzzcocks’ music was much more impactful than their peers’ too. The guitars

were more muscular, the melodies were more prominent, and the band did exciting

things with their songwriting. This isn’t to say bands like The Clash and

Siouxsie and the Banshees didn’t; I just think that what they were doing had

more weight for the time. The likes of ‘Why Can’t I Touch It?’ with its

unbelievably groovy bassline and the power pop of ‘Promises’ are two further

examples of Buzzcocks’ scope. To use a football analogy, they were

well-ingratiated in the men’s team when their peers were still languishing in

the academy.

Musically,

Shelley and Buzzcocks augmented the punk formula. They didn’t confine

themselves to playing just three power chords, and because of this, it wouldn’t

be excessive to label them more art-rock than punk. Ironically, there’s room

for them to be described as the first post-punk band, as they were railing

against the genre even when they were deeply embedded within it. Following

this, there are more parallels between them and Magazine, XTC and Squeeze than

with the likes of Sex Pistols and The Clash. It also says everything that many

subsequent alternative heroes such as The Smiths, Nirvana, Pixies, Pearl Jam

and Green Day cite as them an influence due to their creative prowess. There

was real depth to Buzzcocks, and that was always their power.

Hear Me

Out: Why Buzzcocks are the best first-wave punk band. By Arun Starkey. Far Out Magazine, July 20, 2023.

In January 1977 a young punk band called Buzzcocks walked into the Manchester branch of Virgin with a box of singles they wanted to sell. They had set up a label called New Hormones and paid for the records themselves with an early form of crowdfunding – borrowing £500 from a couple of friends and the guitarist’s dad – and their only ambition was to sell enough of the 1,000 copies they had pressed to be able to repay the loans. The Spiral Scratch EP ended up selling 16,000 copies and reaching the top 40 – there was no problem with the loans. More importantly, though, it proved that it was possible for artists to be in complete control of their music, from production to distribution, and in the process invented indie.

These days,

there’s nothing unusual about bypassing the record industry. Chance the Rapper

self-released his music and has become a breakout star and Barack Obama’s guest

at the White House. In 1977, though, Spiral Scratch was game-changing. In its

wake came a wave of British independent labels and a distribution network that

meant that, as Rough Trade founder Geoff Travis puts it, “anyone could compete

with the big boys, but that only happened because it was an undeniably great

record”.

Few who saw

the first Buzzcocks show on 1 April 1976 would have felt they were in the

presence of people who were about to reshape pop. Peter McNeish and Howard

Trafford (who would become Pete Shelley and Howard Devoto) fronted a makeshift

version of the band at Bolton Institute of Technology’s students’ union – they

were studying there – and managed to annoy not just the venue, but their

bandmates, too.

After the

venue pulled the plug, their drummer – who had never rehearsed with them before

– laid into Shelley and Devoto. “He said: ‘I’m at this level’ – and held his

hands very high,” Shelley, remembers, “‘and you’re down there.’”

Shelley and

Devoto had been inspired to form Buzzcocks seven weeks earlier, when they read

a live review in NME that would transform their lives. The headline, “Don’t

look over your shoulder, but the Sex Pistols are coming!”, was enough to

convince them to borrow a little Renault and drive 200 miles to High Wycombe in

Buckinghamshire to see the Pistols support Screaming Lord Sutch on 21 February.

“Seeing the

Pistols changed everything,” Devoto says. “We started to realise what songs we

ourselves could write.”

At this

point, the Pistols were some way from becoming the band who outraged a nation.

They were so short of bookings that their manager, Malcolm McLaren, agreed to

the offer Shelley and Devoto put to him: they would put his charges on in

Manchester, if they could be the support band.

The problem was, the pair didn’t have a band. And when the night of the gig at the Lesser Free Trade Hall arrived – 4 June 1976, with Shelley and Devoto having paid £32 to rent the room – they still lacked a permanent bassist and drummer and had to drop off the bill. But they quickly recruited bassist Steve Diggle and drummer John Maher, who joined while doing his O-levels as a way of avoiding “aggro” from his neighbours, and when the Pistols returned to the Lesser Free Trade Hall on 20 July, Buzzcocks were ready.

“I thought

if I could join a band, I could get the drum kit out of the house,” Maher says.

“How was I to know that my first gig would be supporting the Sex Pistols?”

Shelley,

who was 22, remembers the show for its “complete lack of adult supervision. We

were literally doing it ourselves. McLaren said: ‘If Buzzcocks aren’t onstage

in 10 minutes, you’re not going on.’ But he was shrewd enough to bring music

journalists.” When the journalists’ reviews appeared, Buzzcocks were catapulted

to national attention.

Initially,

they had no plans to make a record, but after the Pistols’ appearance on Thames

TV’s Today show – swearing at the host, Bill Grundy – landed them on tabloid

front pages and major labels started signing punk bands, Buzzcocks realised

they had to make their mark or risk being passed by.

“Record

company scouts just didn’t venture up to Manchester,” says Richard Boon, their

manager. “The place felt like the tide had gone out.” But what other options

were there? To Shelley, the idea of manufacturing a record themselves felt “as

unfeasible as making a computer in your front room”.

There were

already British independents: the Damned’s New Rose had been released on Stiff,

but that label had the advantage of being run by people with lots of experience

in the music business, and the contacts that came with that experience. It was

a rather different matter for a pair of students whose only experience of

records was buying them and listening to them. “The Drones told us: ‘Don’t do

it!’” Shelley says. “Because they’d gone the vanity publishing route in a

previous incarnation and ended up with boxes of records in the garage.”

However,

the band’s new booking agent, Martin Hannett, wanted to become a producer and

saw an opportunity in Buzzcocks. Boon started investigating pressing plants, to

see whether they really could make a record, and as things started moving,

Shelley began to think: “We can actually do this.”

It helped

that by now they had a set of songs that matched those of any London punk band,

led by Boredom (“You know me – I’m acting dumb / The scene is very humdrum /

Boredom! Boredom!” Devoto sings, while Shelley picks out a two-note solo).

Devoto wrote the lyrics during night shifts at a tile factory, and Shelley

wrote the tunes on his Woolworth’s guitar.

“We were chalk and cheese,” Shelley remembers.

“I said to him, ‘I never get around to things. I live in a straight line,’ That

ended up in Boredom.” Shelly’s’s famous guitar solo – seen as the epitome of

punk’s rejection of musicianship, and later resurrected by Edwyn Collins for

Orange Juice’s Rip It Up – came “out of the blue and seemed to fit. After we’d

finished it, we fell about laughing.”

Boredom,

Breakdown, Time’s Up and Friends of Mine were recorded in 30 minutes just

before Christmas 1976, with Hannett at the controls. Spiral Scratch launched

his career, too, and he would go on to produce Joy Division and New Order, the

Psychedelic Furs, U2, Happy Mondays and many more – including Buzzcocks after

Devoto left, and Devoto’s next group, Magazine.

“My impression was that Martin didn’t know what he was doing,” Maher says. “But neither did we.” Devoto says of Spiral Scratch’s ramshackle, lo-fi sound: “As amateurs even we found it a bit amateurish sounding.”

Boon thinks

the amateurishness is all part of the EP’s charm: Buzzcocks were the

anti-Fleetwood Mac, the antithesis of big-budget music. He took Spiral

Scratch’s cover photo of the band on a Polaroid instant camera and the band

assembled at Devoto’s shared flat in Lower Broughton to slide 1,000 singles

into their budget picture sleeves.

The first

shop to take copies was Virgin in Manchester, which accepted 25 copies and sold

them for 99p each (of which 60p went to the band). In London, Travis had just

opened his Rough Trade shop. He took an initial 50, then ordered 200 more just

two days later. “I knew I could sell them,” he says. “It was a sensational

record.”

Boon didn’t

have the money to press more copies, so Jon Webster, the manager of the

Manchester branch of Virgin, lent him £600 from the shop’s sales of coach

tickets to a Status Quo gig. “So indirectly, the first British independent

success story was financed by the Quo,” Boon says, laughing. Webster remembers

those pioneering punk days as “the best time of my life”, and notes that, back

then, a record shop could be a catalyst for spreading new music. “Because there

was no distribution, almost no shops had these records,” he says. “When we

handed out a photocopied list of all our punk singles at the [venue] Electric

Circus, we were deluged with people from all over the north.”

Soon enough,

a copy of Spiral Scratch reached John Peel, who duly played it; it became

single of the week in the music papers, and sales exploded via mail order.

After Mancunian photographer Kevin Cummins gave Marc Bolan a copy and

photographed him holding it, Boon’s landline started “ringing off the hook”.

Spiral

Scratch provided evidence that punk was having an effect nationwide, that it

wasn’t just confined to a small coterie in London. The cultural historian Jon

Savage had just started his first fanzine when it was released, and it made him

think Manchester punk “seemed more interesting than London punk, which was full

of people with leather jackets and cocaine habits”. Just as important, the

means of Spiral Scratch’s release epitomised liberation through DIY. “Suddenly

the gap between wanting to do something and actually doing it seemed small,”

Savage says.

Devoto’s

idea of providing recording details on the sleeve – “Breakdown, third take, no

overdubs” and so on – further demystified the process of making records, making

it seem accessible to scores of young groups. Two months after Spiral Scratch

was released, the Desperate Bicycles formed, and released a first single with a

sleevenote that read: “The Desperate Bicycles were formed in March 1977 specifically

for the purpose of recording and releasing a single on their own label.” That

note inspired Green Gartside of Scritti Politti to form his own band and

release a debut single on which he itemised the costs of production and

manufacturing. Buzzcocks had started something that couldn’t be stopped.

Indie

labels began to spring up nationwide: in 1978, ZigZag magazine published a list

of 120 labels that had punk acts on their roster; the vast majority of them

were from outside London. Alongside the labels came a new breed of band:

Webster remembers Ian Curtis coming into Virgin and declaring: “I’ve formed a

band!” Then Rough Trade set up the indie distribution network that gave these

new labels and bands some of the muscle their counterparts on the major labels

had previously monopolised. “You could have a No 1 record and have nothing to

do with the record industry,” he says. “It was tremendously empowering.”

Buzzcocks Mk 1 didn’t survive their own earthquake. Devoto returned to college, and later formed Magazine. The new lineup of Buzzcocks, with Shelley singing, signed to United Artists and produced some of the best loved-music of the punk era. Forty years on, although there have been breaks along the way, Shelley and Diggle continue to lead Buzzcocks, and celebrated the band’s 40th anniversary with a world tour.

And all

these years on, there are young bands doing exactly what Buzzcocks did. “I

recently met the grime act Tough Squad, who told me how they press up 200

records, take them to shops and then go back for the money,” Boon says. “Just

like we did.”

“It just

shows what can happen if you’re stupid enough to believe that you can do

something,” Shelley adds. “History is made by those who turn up.”

Spiral Scratch (40th anniversary reissue) is

released on Domino on 27 January. Time’s Up, an album of 1976 demos, is being

reissued on 24 February.

How

Buzzcocks invented indie (with help from the Sex Pistols, a Renault and the

Quo). By Dave Simpson. The Guardian, January 12, 2017.

Pete

Shelley and his band Buzzcocks became indelibly linked to the UK’s punk

movement when they played their first gig supporting the Sex Pistols at the

Lesser Free Trade Hall in Manchester in July 1976, but they never conformed to

any of punk’s cliches about rage, anarchy and rebellion. Shelley, who has died

of a heart attack aged 63, proved to be a songwriter of wit and subtlety, able

to probe the angst and confusion of adolescent love and lust with shrewd

insight.

He was

innovative musically as well as lyrically, taking inspiration from David Bowie,

Brian Eno, Roxy Music and the Velvet Underground, as well as from German bands

such as Neu and Can. While the music of many of the punk bands remains firmly

of its time, Buzzcocks’ best songs still sound fresh and inventive, mixing

dense guitar patterns with infectious melodies. Their influence can be heard on

bands from Primal Scream and the Jesus and Mary Chain to REM and Nirvana. Gary

Kemp of Spandau Ballet said: “Pete was one of Britain’s best pure pop writers,

up there with Ray Davies.”

Buzzcocks

achieved success with their first recording, the Spiral Scratch EP, which was

released on their own label, New Hormones, in January 1977 (the band having

supported the Sex Pistols on their Anarchy tour in late 1976). It was one of

the first independent releases of the punk era, and to the band’s surprise sold

its first thousand copies in four days. “We made quite a bit of money from

Spiral Scratch,” Shelley recalled. “It ended up selling about 16,000 copies and

we were able to buy some new equipment.”

They then

signed to United Artists. Their first single, Orgasm Addict, was released in

November 1977 but the BBC declined to play it because of its subject matter and

it did not make the charts. The follow-up, What Do I Get, released in February

1978, reached 37, and their debut album, Another Music in a Different Kitchen

(1978) climbed to 15. Their second album, Love Bites, which came out later that

year, contained what remains their best-known hit, the zingingly propulsive

Ever Fallen In Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve), which made No 12. Shelley

borrowed the title from a line in the musical Guys and Dolls. The 1979 album A

Different Kind of Tension reached 26 in the UK.

Continued

singles success came with Promises (20), Everybody’s Happy Nowadays (29) and

Harmony in My Head (32). However, growing tensions in the band coupled with

friction with EMI, which had purchased United Artists, prompted Shelley to

break up Buzzcocks in 1981.

He was born

Peter McNeish in Leigh, Lancashire. His father, John, was a fitter at Astley

Green colliery, and his mother, Margaret, a former mill worker. Peter began

writing songs while still at Leigh grammar school, and while studying for an

HND in electronics at Bolton Institute of Technology he bought a Tandberg

four-track reel-to-reel tape recorder and began making recordings of his own

songs. (“I think of my career in music more as a songwriting career than

anything else,” he said in 1983.) He formed a group called Jets of Air, the

name inspired by a college lecture on Newtonian physics, and while “we played

only about six gigs in three years”, Shelley built up a stockpile of songs.

He then

dabbled in a project called Sky, where he experimented with electronic music

and recorded the album Sky Yen, released later, in 1980, on his own label,

Groovy Records. He subsequently tried making “heavier, more rhythmic” music

with Smash, which he described as “a non-existent group”, but which supplied

more raw material for Buzzcocks.

The band

came about when Shelley spotted an advertisement on a college noticeboard from

Howard Devoto (real name Howard Trafford), wanting to form a band in the vein

of the Stooges and the Velvet Underground. “That was much in line with the

Smash idea, so I phoned him up straight away,” said Shelley. Buzzcocks

originally planned to make their debut at the first Sex Pistols concert at the

Lesser Free Trade Hall in June 1976, but the bass player and drummer pulled

out.

For their

eventual appearance the following month, Shelley and Devoto were joined by the

drummer John Maher and the bassist Steve Diggle. When Devoto quit after the

release of Spiral Scratch and went on to form Magazine, Shelley became lead

vocalist, Diggle switched to guitar and the original bass player, Garth Smith,

rejoined temporarily, later replaced by Steve Garvey.

In 1981

Shelley launched his solo career with the single Homosapien, from the album of

the same name, produced by the Buzzcocks producer Martin Rushent (who was about

to help make Human League’s electropop epic Dare). Shelley had returned to his

earlier fondness for electronica, and found himself in controversial waters

when the BBC banned Homosapien for its “explicit reference to gay sex”. In 2002

Shelley commented that his sexuality “tends to change as much as the weather”.

The track reached 14 on the US dance chart.

In 1983 his second solo album, XL1, brought him a minor hit single with Telephone Operator. In 1987 he contributed the song Do Anything to the soundtrack of the John Hughes movie Some Kind of Wonderful.

In 1989

Buzzcocks reformed and toured the US, and released Trade Test Transmissions

(1993), the first of a series of albums, the most recent of which was The Way

(2014). In 2002, Shelley reunited with Devoto to record the album Buzzkunst.

“Devoto is not the life and soul of the party or a born raconteur, but he sees

things as funny and I think that’s how we hit it off with each other,” Shelley

observed drily. “I always had this idea that me and Devoto were like Gilbert

and George. As long as you approach it from that angle you can do anything you

want, and you just call it art.”

In 2005,

following the death of the DJ John Peel, Shelley recorded a tribute version of

Ever Fallen In Love with a multi-platinum lineup of stars including Elton John,

Robert Plant, David Gilmour and Roger Daltrey.

In 2012 he

moved to Tallinn, Estonia, with his second wife, Greta. She survives him, as do

his younger brother, Gary, and a son from his first marriage.

Pete Shelley (Peter Campbell McNeish),

musician, singer and songwriter, born 17 April 1955; died 6 December 2018.

Pete

Shelley obituary. By Adam Sweeting. The Guardian, December 7, 2018.

Buzzcocks'

Pete Shelley – a life in pictures. The Guardian, December 7, 2018.