The

British Library reading room smelled like old pages. I stared at the stack of

women’s history books I had ordered—not too many, I reassured myself, not too

overwhelming. The one on the bottom was the most unusual: hard-backed and bound

in a worn, blue fabric, with yellowing, deckled edges. I opened it first and

found virtually two hundred sheets of tiny script—in Yiddish. It was a language

I knew but hadn’t used in more than fifteen years. I nearly returned it to the

stacks unread. But some urge pushed me to read on, so, I glanced at a few

pages. And then a few more. I’d expected to find dull, hagiographic mourning

and vague, Talmudic discussions of female strength and valor. But

instead—women, sabotage, rifles, disguise, dynamite. I’d discovered a thriller.

Could

this be true?

I was

stunned.

I had

been searching for strong Jewish women.

In my

twenties, in the early 2000s, I lived in London, working as an art historian by

day and a comedian by night. In both spheres, my Jewish identity became an

issue. Underhanded, jokey remarks about my semitic appearance and mannerisms

were common from academics, gallerists, audiences, fellow performers, and

producers alike. Gradually, I began to understand that it was jarring to the

Brits that I wore my Jewishness so openly, so casually. I grew up in a

tight-knit Jewish community in Canada and then attended college in the

northeast United States. In neither place was my background unusual; I didn’t

have separate private and public personas. But in England, to be so “out” with

my otherness, well, this seemed brash and caused discomfort. Shocked once I

figured this out, I felt paralyzed by self-consciousness. I was not sure how to

handle it: Ignore? Joke back? Be cautious? Overreact? Underreact? Go undercover

and assume a dual identity? Flee?

I turned

to art and research to help resolve this question and penned a performance

piece about Jewish female identity and the emotional legacy of trauma as it

passed over generations. My role model for Jewish female bravado was Hannah

Senesh, one of the few female resisters in World War II not lost to history. As

a child, I attended a secular Jewish school—its philosophies rooted in Polish

Jewish movements—where we studied Hebrew poetry and Yiddish novels. In my

fifth-grade Yiddish class, we read about Hannah and how, as a

twenty-two-year-old in Palestine, she joined the British paratroopers fighting

the Nazis and returned to Europe to help the resistance. She didn’t succeed at

her mission but did succeed in inspiring courage. At her execution, she refused

a blindfold, insisting on staring at the bullet straight on. Hannah faced the

truth, lived and died for her convictions, and took pride in openly being just

who she was.

That

spring of 2007, I was at London’s British Library, looking for information on

Senesh, seeking nuanced discussions about her character. It turned out there

weren’t many books about her, so I ordered any that mentioned her name. One of

them happened to be in Yiddish. I almost put it back.

Instead,

I picked up Freuen in di Ghettos (Women in the Ghettos), published in New York

in 1946, and flipped through the pages. In this 185-page anthology, Hannah was

mentioned only in the last chapter. Before that, 170 pages were filled with

stories of other women—dozens of unknown young Jews who fought in the

resistance against the Nazis, mainly from inside the Polish ghettos. These

“ghetto girls” paid off Gestapo guards, hid revolvers in loaves of bread, and

helped build systems of underground bunkers. They flirted with Nazis, bought

them off with wine, whiskey, and pastry, and, with stealth, shot and killed

them. They carried out espionage missions for Moscow, distributed fake IDs and

underground flyers, and were bearers of the truth about what was happening to

the Jews. They helped the sick and taught the children; they bombed German train

lines and blew up Vilna’s electric supply. They dressed up as non-Jews, worked

as maids on the Aryan side of town, and helped Jews escape the ghettos through

canals and chimneys, by digging holes in walls and crawling across rooftops.

They bribed executioners, wrote underground radio bulletins, upheld group

morale, negotiated with Polish landowners, tricked the Gestapo into carrying

their luggage filled with weapons, initiated a group of anti-Nazi Nazis, and,

of course, took care of most of the underground’s admin.

Despite

years of Jewish education, I’d never read accounts like these, astonishing in

their details of the quotidian and extraordinary work of woman’s combat. I had

no idea how many Jewish women were involved in the resistance effort, nor to

what degree.

These

writings didn’t just amaze me, they touched me personally, upending my

understanding of my own history. I come from a family of Polish Jewish

Holocaust survivors. My bubbe Zelda (namesake to my eldest daughter) did not

fight in the resistance; her successful but tragic escape story shaped my

understanding of survival. She—who did not look Jewish, with her high

cheekbones and pinched nose—fled occupied Warsaw, swam across rivers, hid in a

convent, flirted with a Nazi who turned a blind eye, and was transported in a

truck carrying oranges eastward, finally stealing across the Russian border,

where her life was saved, ironically, by being forced into Siberian work camps.

My bubbe was strong as an ox, but she’d lost her parents and three of her four

sisters, all of whom had remained in Warsaw. She’d relay this dreadful story to

me every single afternoon as she babysat me after school, tears and fury in her

eyes. My Montreal Jewish community was composed largely of Holocaust survivor

families; both my family and neighbors’ families were full of similar stories

of pain and suffering. My genes were stamped—even altered, as neuroscientists

now suggest—by trauma. I grew up in an aura of victimization and fear.

But

here, in Freuen in di Ghettos, was a different version of the women-in-war

story. I was jolted by these tales of agency. These were women who acted with

ferocity and fortitude—even violently—smuggling, gathering intelligence,

committing sabotage, and engaging in combat; they were proud of their fire. The

writers were not asking for pity but were celebrating active valor and

intrepidness. Women, often starving and tortured, were brave and brazen.

Several of them had the chance to escape yet did not; some even chose to return

and battle. My bubbe was my hero, but what if she’d decided to risk her life by

staying and fighting? I was haunted by the question: What would I do in a

similar situation? Fight or flight?

At

first, I imagined that the several dozen resistance operatives mentioned in

Freuen comprised the total amount. But as soon as I touched on the topic,

extraordinary tales of female fighters crawled out from every corner: archives,

catalogues, strangers who emailed me their family stories. I found dozens of

women’s memoirs published by small presses, and hundreds of testimonies in

Polish, Russian, Hebrew, Yiddish, German, French, Dutch, Danish, Greek,

Italian, and English, from the 1940s to today.

Holocaust

scholars have debated what “counts” as an act of Jewish resistance. Many take

it at its most broad definition: any action that affirmed the humanity of a

Jew; any solitary or collaborative deed that even unintentionally defied Nazi

policy or ideology, including simply staying alive. Others feel that too

general a definition diminishes those who risked their lives to actively defy a

regime, and that there is a distinction between resistance and resilience.

The

rebellious acts that I discovered among Jewish women in Poland, my country of

focus, spanned the gamut, from those involving complex planning and elaborate

forethought, like setting off large quantities of TNT, to those that were

spontaneous and simple, even slapstick-like, involving costumes, dress-up,

biting and scratching, wiggling out of Nazis’ arms. For many, the goal was to

rescue Jews; for others, to die with and leave a legacy of dignity. Freuen

highlights the activity of female “ghetto fighters”: underground operatives who

emerged from the Jewish youth group movements and worked in the ghettos. These

young women were combatants, editors of underground bulletins, and social

activists. In particular, women made up the vast majority of “couriers,” a

specific role at the heart of operations. They disguised themselves as non-Jews

and traveled between locked ghettos and towns, smuggling people, cash,

documents, information, and weapons, many of which they had obtained

themselves.

In

addition to ghetto fighters, Jewish women fled to the forests and enlisted in

partisan units, carrying out sabotage and intelligence missions. Some acts of

resistance occurred as “unorganized” one-offs. Several Polish Jewish women

joined foreign resistance units, while others worked with the Polish

underground. Women established rescue networks to help fellow Jews hide or

escape. Finally, they resisted morally, spiritually, and culturally by

concealing their identities, distributing Jewish books, telling jokes during

transports to relieve fear, hugging barrack-mates to keep them warm, and setting

up soup kitchens for orphans. At times this last activity was organized,

public, and illegal; at others, it was personal and intimate.

Months

into my research, I was faced with a writer’s treasure and challenge: I had

collected more incredible resistance stories than I ever could have imagined.

How would I possibly narrow it down and select my main characters?

Ultimately,

I decided to follow my inspiration, Freuen, with its focus on female ghetto

fighters from the youth movements Freedom (Dror) and The Young Guard (Hashomer

Hatzair). Freuen’s centerpiece and longest contribution was written by a female

courier who signed her name “Renia K.” I was intimately drawn to Renia—not for

being the most well-known, militant, or charismatic leader, but for the

opposite reason. Renia was neither an idealist nor a revolutionary but a savvy,

middle-class girl who happened to find herself in a sudden and unrelenting

nightmare. She rose to the occasion, fueled by an inner sense of justice and by

anger. I was enthralled by her formidable tales of stealing across borders and

smuggling grenades, and by the detailed descriptions of her undercover

missions. At age twenty, Renia recorded her experience of the preceding five

years with even-keeled and reflective prose, vivid with quick

characterizations, frank impressions, and even wit.

Later, I

found out that Renia’s writings in Freuen were excerpted from a long memoir

that had been penned in Polish and published in Hebrew in Palestine in 1945.

Her book was one of the first (some say the first) full-length personal

accounts of the Holocaust. In 1947 a Jewish press in downtown New York released

its English version with an introduction by an eminent translator. But soon

after, the book and its world fell into obscurity. I have come across Renia

only in passing mentions or scholarly annotations. Here I lift her story from

the footnotes to the text, unveiling this anonymous Jewish woman who displayed

acts of astonishing bravery. I have interwoven into Renia’s story tales of

Polish Jewish resisters from different underground movements and with diverse

missions, all to show the breadth and scope of female courage.

From the

book The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in

Hitler’s Ghettos by Judy Batalion.

Uncovering

the Stories of the Jewish Women Resistance Fighters in Nazi-Occupied Poland. By

Judy Batalion. LitHub , April 6, 2021.

Spring

1943. It had been six months since Renia Kukiełka had arrived in Bedzin, a town

in southwest Poland now annexed by the Third Reich. After fleeing a ghetto,

escaping a forced labor camp, running through forests, jumping off a moving

train, and pretending to be a Christian housekeeper, nervously genuflecting at

weekly church services, she’d come here to join her sister in the Jewish

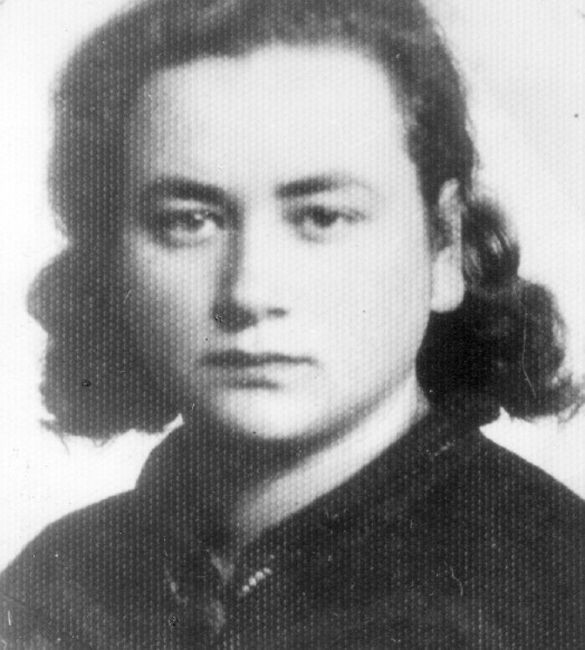

underground. Renia, aged nineteen, quickly became a “courier” — in Hebrew, a

“kasharit,” or connector. “Courier girls” risked death to connect the locked

ghettos where Jews were imprisoned. They dyed their hair blond, took off their

armbands, put on dazzling fake smiles, and secretly slipped in and out of

ghettos and camps, bringing Jews information, supplies and hope. On her first

missions, Renia was sent to obtain intelligence, transfer currency and purchase

fake IDs. Now, the resistance needed weapons.

She was

paired with twenty-two-year-old Ina Gelbart, whom Renia described as “a lively

girl. Tall, agile, sweet…. Never for a moment feared death.”

Renia

and Ina had fake papers enabling them to travel. Obtained from an expert

counterfeiter in Warsaw, they’d cost a fortune, but as Renia reflected, it was

hardly the time to negotiate a bargain. When the girls arrived at the

checkpoint, they assuredly handed over government-issued transit permits and

identity cards, inlaid with their portraits.

The

guard nodded.

Renia

was by now confident operating in Warsaw, and she and Ina set out to find their

contact, Tarlow, a Jew who disguised himself as a Christian and lived on the

Aryan side. He had connections.

The

revolvers and grenades that Renia smuggled came primarily from the Germans’

weapons storehouses. “One of the soldiers used to steal and sell them,” Renia

explained, “then another sold them; we got them from perhaps the fifth hand.”

Other women’s accounts speak of weapons coming from German army bases, weapons

repair shops, and factories where Jews were used as forced labor, as well as

from farmers, the black market, dozing guards, the Polish resistance, and even

Germans who sold guns they’d stolen from Russians. After losing Stalingrad in

1943, German morale fell, and soldiers sold their own guns. Though rifles were

easiest to come by, they were hard to carry and hide; pistols were more

efficient and more expensive.

Sometimes,

Renia explained, a weapon was smuggled all the way to the ghetto only for them

to find that it was too rusty to fire or did not come with compatible bullets.

There was no way to try before you buy. “In Warsaw, there was no time or place

to try out the weapons. We had to quickly pack any defective one up in a

concealed corner and get back on the train to Warsaw to exchange it for a good

one. Again, people risked their lives.”

The

girls found Tarlow, and he directed them to a cemetery. That’s where they’d buy

the cherished merchandise: explosives, grenades, and guns, guns, guns.

To

Renia, each weapon smuggled in was “a treasure.”

In all

the major ghettos, the Jewish resistance was established with barely any arms.

At first, the Białystok underground had one rifle that had to be carried

between units of fighters so that each could train with a real weapon; in

Vilna, they shared one revolver and shot against a basement wall of mud so they

could reuse the bullets. Kraków began without a single gun. Warsaw had two

pistols to start.

The

Polish underground promised arms, but these shipments were often canceled, or

stolen en route, or delayed indefinitely. The kashariyot were sent out to find

weapons and ammunition and smuggle them to ghettos and camps, often with little

guidance, and always at tremendous risk.

The

courier girls’ psychological skills were especially important in this most

dangerous task. Their connections and expertise in hiding, bribing, and

deflecting suspicion were critical. Frumka Płotnicka was the first courier to

smuggle weapons into the Warsaw ghetto: she placed them at the bottom of a sack

of potatoes. Adina Blady Szwajger did the same with ammunition, and one time,

when a patrol ordered her to open her bag, her smile and the cocky way in which

she opened it saved her. Bronka Klibanski, a courier in Białystok, was

smuggling a revolver and two hand grenades inside a loaf of country bread in

her suitcase. At the train station, a German policeman asked her what she was carrying.

By “confessing” that she was smuggling food, she managed to avoid having to

open her bag. Her “honest confession” evoked a protective response from the

policeman, who instructed the train conductor to take care of her and make sure

no one bothered her or her suitcase.

Renia

knew she wasn’t the first courier to bring in booty for a rebellion: kashariyot

had obtained and transported weapons into the ghettos for both the Kraków and

Warsaw revolts. When Hela Schüpper, a master courier in Kraków, was sent to

Warsaw to buy guns, she knew she’d be spending twenty hours undercover on

trains. She scraped her face with special soap to hide her scabies, dyed her

hair bright blonde (using a potent blue capsule of bleach), tied her hair in a

turban-like scarf, borrowed a stylish outfit from a non-Jewish friend’s mother,

and purchased an expensive jute handbag with a floral print, fashionable in

war-time. She looked like she was on her way to an afternoon of theater.

Instead, she met a People’s Army contact, Mr. X, at the gate of a clinic. She

was told he’d be reading a newspaper. As per instructions, she asked him for

the time and to see his newspaper. He walked away, and Hela followed at a

distance, embarking a different train car and landing at a shoemaker’s

apartment.

Hela

waited several days for the goods: five weapons, four pounds of explosives, and

clips of cartridges. She taped the handguns to her skin and hid the ammo in her

chic purse. She did not go to the theater; she was the theater. A photo of her

in Aryan Warsaw shows her smiling, content, wearing a tailored skirt suit that

ends just above the knee, loafers, an updo, and a lapel pin; she clutches a

small, stylish tote. As courier Gusta Davidson described Hela: “Anyone who

observed the way she flirted shamelessly on the train . . . flashing her

provocative smile, would have assumed she was on her way to visit her fiancée

or to go on vacation.” (Even Hela got caught on occasion. Once, she broke out

of a jail bathroom and bolted. She never wore long coats on missions, making

sure to keep her legs unencumbered.)In

Warsaw, underground members on the Aryan side spent months trying to obtain

weapons. Posing as Poles, they used basements or convent restaurants for quiet

meetings, changing subjects whenever the waitress approached. Vladka Meed began

by smuggling metal files into the ghetto — these were for Jews to carry so that

if they were shoved onto a train to Treblinka, they could cut through the

window bars and jump. She dressed like a peasant, headed to a Gentile smuggling

area, and jumped over the wall. Some couriers paid Polish guards to whisper a

password at the wall; a resistance member waiting inside would climb up and

grab the package. Vladka procured her first gun from her landlord’s nephew for

2,000 złotys. She paid her landlord 75 złotys to put the box through a hole, or

meta, in the wall, in an area where guards were easily bribed. People bearing

“gifts” also passed to and from the Aryan side by joining labor groups and

jumping off trains that ran through the ghetto. Items were smuggled in garbage

trucks and ambulances, and sent through drainpipes. In Warsaw, many couriers

used the courthouse, which had entrances on both the Jewish and Aryan sides.

Once,

Vladka had to repack three cartons of dynamite into smaller packages and pass

them through the grate of a factory window in the subcellar of a building that

bordered the ghetto. As she and the Gentile watchman, who had been bribed with

300 złotys and a flask of vodka, worked frantically in the dark, “the watchman

trembled like a leaf,” she recalled. “I’ll never take such a chance again,” he

mumbled when they finished, drenched in sweat. When Vladka left, he asked her

what was in the packages. “Powdered paint,” she replied, careful to gather up

some spilled dynamite from the floor.

Havka

Folman and Tema Schneiderman smuggled grenades into the Warsaw ghetto in

menstrual pads, and in their underwear. As they rode through the city in a

crowded streetcar, a seat became available and a Pole chivalrously insisted

Tema take it. If she sat down, however, they all might explode. The girls

chatted their way out of it, their loud laughter covering their tremendous

fear.

In

Białystok, courier Chasia Bielicka did not work alone. Eighteen Jewish girls

collaborated to arm the local resistance, while leasing rooms from Polish

peasants, and holding day jobs in Nazi homes, hotels, and restaurants. Chasia

was a maid for an SS man who had an armoire filled with handguns to shoot

birds. Chasia periodically grabbed a few bullets and dropped them into her coat

pocket. Once, he called her over to the cupboard in a rage; she was sure she’d

been caught, but he was upset only because the weaponry wasn’t adequately

organized. The courier girls stashed ammo under their rooms’ floorboards, and

passed machine-gun bullets to the ghetto through the window of a latrine that

bordered the ghetto wall.

After

the Białystok ghetto’s liquidation and the youth’s revolt, the courier ring

continued to supply intelligence and arms to all sorts of partisans, enabling

them to break into a Gestapo arsenal. To get a large gun to the forest, the

girls transported each steel piece on a separate journey. Chasia carried a long

rifle in broad daylight in a metal tube that resembled a chimney. Suddenly two

gendarmes appeared in front of her. Chasia knew if she didn’t speak first, they

would. So she asked them for the time.

“What,

it’s already so late?” she exclaimed. “Thank you, they’ll be worried about us

at home.” As Chasia put it, “feigning extreme confidence,” was her undercover

style. In offices, she’d complain to the Gestapo if she had to wait long for

her (fake) ID. On one occasion, a Nazi saw her trying to enter the ghetto, and,

without thinking, she pulled down her pants and urinated, throwing him off.

Similarly, if a Polish woman was suspicious of a Jewish man, he was wise to

immediately offer to drop his pants and prove his lack of circumcision—this was

usually enough to startle and repel her.

Chasia

got a new day job; her new boss was a German civilian who worked for the German

army as a building director. She knew he’d helped feed his Jewish workers, and

one night she told him she was a Jew herself. Her roommate, Chaika Grossman,

who’d led the Białystok uprising and fled the deportation, also worked for an

anti-Nazi German. The five courier girls who were still alive initiated a cell

of rebellious Germans. When the Soviets arrived in the area, they introduced

them too and chaired the Białystok Anti-Fascist Committee, composed of all

local resistance organizations. The girls passed guns from the friendly Germans

to the Soviets, provided all the intelligence for the Red Army’s occupation of

Białystok, and collected weapons for them from fleeing Axis soldiers.

In

Warsaw, too, after the ghetto uprising, fighters needed weapons for defense, as

well as for revolts in other camps and ghettos, like Renia’s. Leah Hammerstein

worked on the Aryan side as a kitchen helper in a rehab hospital. Her

underground comrade once stunned her by asking if she might be willing to steal

a gun. He never mentioned it again, but Leah became obsessed with the idea. One

day, she passed an empty German soldiers’ room. Without thinking, she

approached the closet, and a pistol was right there, waiting for her. She

slipped it under her dress, then walked to the bathroom and locked the door.

What now? She stood on the toilet and noticed a small window that opened onto

the roof. She wrapped the gun in her underwear and slipped it out. Later, when

it was her turn to throw out potato peelings, she went up to the roof,

retrieved it, and threw it into the hospital garden. A hospital wide search

ensued, but she wasn’t worried — no one would suspect her. At the end of her

shift, she picked the wrapped gun out of the weeds, put it in her purse, and

went home.

From the

book : The Light of Days : The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in

Hitler's Ghettos by Judy Batalion.

'The

Light Of Days' Tells The Stories Of Young Jewish Women Resistance Fighters In

WWII Poland. By Peter O'Dowd and Allison Hagan. WBUR , April 5, 2021.

In this

episode of "Keen On", Andrew is joined by Judy Batalion, the author

of "The Light of Days", to discuss a largely untold story of the

holocaust, the story of the young Jewish women who formed a resistance movement

and fought back against the Nazis.

Judy was

born and raised in Montreal, where she grew up speaking English, French,

Yiddish and Hebrew, and trying to stay warm. She studied the history of science

at Harvard then moved to London to pursue a PhD in art history. All the while,

she worked as a curator, researcher, editor, lecturer, comic, MC,

script-reader, dramaturge, performer, actor, producer, translator, muffins

server, and a temp – at a temp agency. Eventually, Judy transformed these

experiences into material, and wrote essays and articles for the New York

Times, the Washington Post, Vogue, the Forward, Salon, the Jerusalem Post and

many other publications. Her stories about family relationships, the

generational transmission of trauma, pathological hoarding and militant

minimalism came together in her book White Walls: A Memoir About Motherhood,

Daughterhood, and the Mess in Between (NAL/Penguin, 2016). White Walls was

optioned by Warner Brothers for whom Judy is currently developing the TV series

“Cluttered.”

Back in

2007, during her phase of career promiscuity, Judy was doing research on strong

Jewish women at the British Library when she happened to come across a dusty,

old Yiddish book. Freuen in die Ghettos (Women in the Ghettos), a Yiddish

thriller about “ghetto girls” who hid revolvers in teddy bears, bribed Nazis

with whiskey and pastry, and blew up German supply trains, became the

inspiration for The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance

Fighters in Hitler’s Ghettos (William Morrow/HarperCollins, 2021). The Light of

Days will be published across Europe, and in Brazil and Israel, and was

optioned by Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Partners, for whom Judy is co-writing the

screenplay.

Judy

Batalion on The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler's Ghettos |

Keen On. Now TV , April 5, 2021.

It takes

something special to be even more astounding than a Matt Gaetz alibi, but Judy

Batalion’s new book, “The Light of Days,” achieves that and much, much more.

Even the

book’s subtitle – “The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler’s

Ghettos” – doesn’t do justice to the amazing tales recounted in this labor of

love from the Canadian-born New Yorker.

The 20

young Jewish women she spotlights lived remarkable lives during World War II,

and it’s easy to see why Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment snapped up the

film rights at manuscript stage in 2018.

Batalion,

44 this month, is currently co-writing the screenplay, and while no director is

currently attached, many of the true stories here feel like something from the

mind of Quentin Tarantino (think “Inglorious Basterds”) rather than a more

traditional Holocaust drama like “Schindler’s List.”

Take,

for example, the story of Bela Hazan, a fearless 19-year-old from southeastern

Poland who took a job working in, of all places, a Gestapo office. This was the

perfect cover for her to act as a courier for a rebel group from the Dror youth

movement, smuggling news bulletins, money and weaponry across Nazi-occupied

Poland. (Dror and other youth movements like Hashomer Hatzair became a de facto

Jewish resistance network in the war.)

Then

there’s Renia Kukielka, who was just 14 at the start of the war but went on to

become a crucial courier ferrying messages between ghettos. Or Zivia Lubetkin,

who was in her mid-20s when she played a key – yet long overlooked – role in

the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of April 1943 as part of the Jewish Fighting

Organization (also known by its Polish acronym, the ZOB).

“The

Light of Days” – the book’s title comes from a line written by a young Jewish

girl for a ghetto song contest – is both a profoundly moving and breathtaking

read, full of tragic and audacious stories. Yet it also provokes anger that it

has taken some 75 years for these stories to themselves see the light of day

and for these acts of heroism finally to be acknowledged.

Some of

the young women Batalion showcases were partisans, literally fighting the Nazis

deep within the forests of Eastern Europe. Many others operated as couriers,

bringing news of Nazi atrocities to Poland’s 400-plus ghettos or smuggling in

munitions, cash and even fighting spirit.

Why were

women chosen for these tasks? Obviously, there was no way for the Nazis to

physically prove a woman was Jewish. But equally importantly, many were more

familiar with Polish culture than their male peers and could blend in more

easily. These were educated young women who could think on their feet and

“pass” as their Aryan compatriots.

“The

Light of Days” begins with the war’s most celebrated Jewish resistance fighter,

Hannah Szenes. It was while researching a story on her, at the British Library

in London in the spring of 2007, that Batalion discovered a very dusty blue

volume among the small pile of books about the volunteer parachutist.

She almost set it aside, but the historian in

her forced her to pick it up and examine it. It was an unusual book for the

British Library to hold, since it was in Yiddish. But that wasn’t the only

unusual thing: Batalion actually speaks Yiddish too, so was able to read the

1946 book, called “Freuen in di Ghettos” (“Women in the Ghettos”).

“The

last chapter was on Hannah Szenes, but before that were 175 pages of stories

about other Jewish women who fought Nazis,” Batalion tells Haaretz in a phone

interview. “The chapters had titles like ‘Ammunition’ and ‘Partisan Battles,’

and in one part there was an ode to guns,” she recalls. “It was so not what I

expected, and so foreign to the Holocaust narrative I had grown up with. It

really startled me.”

Batalion

comes from a family of Polish-born Holocaust survivors and grew up in a

tight-knit Jewish community in Montreal, but says much of her early life was

“an attempt to run away from that.” Hence, she found herself in London,

performing stand-up comedy and working in the art world, but with questions

gnawing away about her Jewish heritage.

But 2007

wasn’t the right time for her to “emotionally commit” to such a mentally

exhausting project. “The last place I wanted to be at that time in my life was

spending my afternoons in 1943 in Warsaw – emotionally, socially,

intellectually,” she recalls. “To write this kind of book, I would have to sit

with dozens, even hundreds, of these testimonies, and I wasn’t ready to do that

until later in my life.”

Still, Batalion

applied for and received a grant to translate “Freuen” into English, which took

about five years (“It was a very complicated translation because, first of all,

my Yiddish was rusty – I don’t use Yiddish that much in my daily life. It was

also a more Germanic Yiddish, and I grew up with a more Polish Yiddish”). She

then briefly tried turning the story of Renia Kukielka into a novel, combining

her wartime exploits with elements of the author’s own grandmother’s life.

“And

finally, in 2017, it was my literary agent who asked me, ‘Wait, what? This

really happened?’ She was the one who told me, ‘You have to write this as a

nonfiction book. It’s very important to tell the true story,’” Batalion

recounts. And that’s how we find ourselves in the rare position of having to

praise an agent for their efforts on our behalf.

“Freuen”

was just the starting point for “The Light of Days,” though. That source

material was “like a scrapbook,” Batalion says, comprising clippings from

different newspapers, obituaries, speeches and memoirs about female fighters

from Jewish youth movements. Her own extensive research included revisiting

numerous wartime sites across Poland, reading and watching whatever testimonies

existed, and interviewing the families of the women who survived the war.

But the

biggest initial challenge was to work out the chronology of events and how lots

of separate stories might mesh together. “It took me about six months to do a

rough first draft,” she says. “I’m writing history out of memoir, so I had to

put together what happened, and when. I was working with personal stories: You can

have a whole memoir that takes place in one week and the rest of the war takes

up one page, so I had to figure out how these stories worked together.”

“The

people who had survived, or had survived long enough to write about their

experiences, were characters that I could focus on, because they had left more

detailed, robust stories,” she explains.

Then

there was the small matter of trying to verify stories that haven’t been told

in nearly 80 years, if at all, and were sometimes written when typewriters,

pens and paper weren’t exactly easy to access.

“The

book has 65 pages of endnotes and a lot of them say, ‘I took this from this

section and this from this, and this memoir said this and in this testimony it

said something a little different,’” Batalion says. “I tried to piece together

stories, and a lot of times the details did conflict – what happened in one

account isn’t exactly the same as in another account. But the accounts often

refer to the same events, which was also exciting as a researcher. They’re all

talking about that day in 1942. I had to decide what version seemed the most

historically accurate and made sense.”

Another

challenge in a book like this is getting the right balance between the “heroes”

and “martyrs,” to use the Hebrew term for Israel’s Holocaust Remembrance Day –

which, significantly, occurs on the anniversary of the start of the Warsaw

Ghetto Uprising.

“There

were a lot of balances to get right,” Batalion notes. “I’m writing here in the

U.S., where a huge percentage of the millennial population doesn’t even know

what Auschwitz is,” she says, referring to the 2018 survey that found

two-thirds of millennials had never heard of the death camp. “It’s very tricky

to tell a story about the Holocaust, because I want to explain the deeply

horrific nature of this genocide, but I also want to tell a story of the people

that fought it.

“A

scholar who wrote a book about humor in the Holocaust wrote, ‘If you want to

write about humor in the Holocaust, the danger is that it seems like the

Holocaust wasn’t that bad.’ This resonated with me. I didn’t want to make it

sound like there was a massive Jewish army who was fighting the Nazis. This was

a horrific genocide, and these were teenagers who tried to organize to

overcome.”

The

author didn’t make life easy for herself by choosing to relate the stories of

tens of different women (the film, by necessity, will have to focus on a couple

of leading characters), and Batalion says this was her most difficult writing

decision. “This wasn’t a story of just two or three women – this was a movement

of organized resistance across the country that involved hundreds, if not

thousands, and it was important that that came across,” she explains.

The

author’s research uncovered “more incredible resistance stories” than she “ever

could have imagined,” but I wonder if she found any common traits among these

young women to help explain their apparent fearlessness.

“You

know, I’ve thought about this a lot,” she says. “I think their bold and savvy

behavior was shaped by their training, by their youth movements and how they

were educated – but I also think many of these women had a very strong sense of

instinct, and followed it. I’m always obsessed with people that I feel have

what I lack.”

She

recounts a meeting with Renia Kukielka’s family in Israel a few years ago.

“They said to me, just in passing, ‘Renia wasn’t someone who, when she crossed

the street, would look left and right, left and right.’ And that stayed with

me, because I am someone who looks left and right, left and right, left and

right. I think many of these rebels had strong impulses and trusted their gut

and just moved.”

“The Light

of Days” conjures up many indelible images: women hiding razor blades in their

hair; secret libraries and makeshift weapons labs being established in ghettos;

female couriers donning layers of skirts to hide contraband in the folds; and

young women determined not to “go like sleep to the slaughter,” to quote Jewish

partisan leader Abba Kovner’s resistance mantra.

Two

other things leap out at you. One is to be reminded of the sheer scale of the

Nazi killing machine, with the Germans establishing over 400 ghettos across

Poland alone. For Batalion, “it’s both the big numbers and the smallness of the

places that overwhelm. Over 400,000 Jews were forced to live in the Warsaw

ghetto alone. That’s a huge number. I was also shocked by the scope of

resistance participation: Over 90 European ghettos had armed Jewish underground

movements. I’d had no idea.

“And

then, on the other hand, there’s the smallness. When you go to these towns and

walk through the streets of former ghettos, they’re just small-town streets.

Even some of the camps that I visited, they’re very human in size – in my head

they loomed so large. The Gestapo headquarters [in Warsaw] is a four-story

building, it’s so regular – which is equally troubling, in a way.”

The

second thing that strikes you is the joie de vivre exhibited by so many of

these young Jews, despite – or perhaps because of – the horrors of everyday

ghetto life. Indeed, a recurring question as you read the book is, when did

these people ever sleep?

Batalion:

“Every testimony I read, every memoir I read, was just so full of action – they

were so alive. These were stories of constant activity, and they drew me in.

These women were literally jumping off trains, running between towns, getting

dressed up, dyeing their hair. These were stories with so much action, and I think

that also just changed the tone of the Holocaust narrative for me. It’s so

different from the more staid narrative I had been exposed to.”

It is

also impossible not to read “The Light of Days” and see it as the current

Polish government’s worst nightmare in light of its controversial, some would

say revisionist, stance regarding the role its citizens played in World War II:

a book that presents the Holocaust in all its complexities, depicting some

non-Jewish Poles as heroes but many others as aiding and abetting the Nazis or

committing their own atrocities.

The good

news is that “The Light of Days” will be published in Poland next year, so

locals will be able to make up their own minds, while Batalion has only good

things to say about the Poles who assisted her in the writing process.

“My only

reactions have been from people who helped me do research in Poland –

translators, research assistants, drivers, fixers – and I honestly felt that

they were as interested in this story as I was,” she says. “They were so

passionate about it, this was so important to them. To them, this is Polish

history; this is their story too. For me too, this is a Polish history book.

“I made

fascinating connections in Poland, mainly with young people in their 20s and

30s. At my Polish publisher, I was saying casually that all four of my

grandparents were from Poland and they laughed, saying, ‘You’re more Polish

than any of us!’ I have a fraught and complicated relationship to Poland, but I

was taken by how passionate these young Poles were about my project.”

Polish

historian Emanuel Ringelblum, the noted chronicler of Warsaw ghetto life, is

quoted in Batalion’s book describing how the women put themselves “in mortal

danger every day” to “carry out the most dangerous missions. … Nothing stands

in their way. Nothing deters them.” Yet his prediction that “the story of the

Jewish women will be a glorious page in the history of Jewry during the present

war” turned out to be far from accurate.

Why has

it taken so long for these stories to finally be told and for these women to

get their “three lines in history,” as one young ghetto activist puts it?

Batalion has her own theories.

“The

story of why I don’t know this story is to me as interesting as the story

itself,” she says. “There are many reasons why this tale disappeared – some of

them have to do with the Zeitgeist and the interests of the times; some of them

have to do with politics. And some of them are very personal. “These women

didn’t tell their story. Or they told them right after the war, like Renia, and

that was it. The telling was in a sense the therapy, or part of the therapy,

and then they had to move on. It was so important to start afresh. As I mentioned

in the book, some of these women weren’t believed. Some of them were accused of

leaving their families or sleeping their way to safety. Many of these women

suffered terrible survivor’s guilt.

“So,

things were silenced for many reasons, and a lot of it had to do with these

women feeling very determined to create families, to create a new generation of

Jews – and they didn’t want to hurt them. They wanted their children to be

healthy and happy and normal.”

As her

own toddler starts screaming in the background, demanding her attention,

Batalion just has time to express her hopes for a book 14 years, or perhaps

several lifetimes, in the making: “I just want people to know these stories. I

want people to know their legacy. I want people to know the names of these

women who fought against all odds for our collective justice and liberty.”

The

Young Jewish Women Who Fought the Nazis – and Why You’ve Never Heard of Them.

By Adrian hennigan. Haaretz, April 6,

2021.

Judy

Batalion was raised in Montreal surrounded by Holocaust survivor families with

stories of loss and suffering. “My genes were stamped — even altered, as

neuroscientists now suggest — by trauma,” she writes in “The Light of Days.” “I

grew up in an aura of victimization and fear.”

In her

20s, while working in London as an art historian (by day) and a comedian (by

night), Batalion began searching for a different perspective on women in the

war. She found it in the forgotten stories of Polish “ghetto girls” — dozens of

Jewish women who did not ask “for pity” or flee the Nazis. Instead, they stayed

and fought them. Or flirted with them, then shot and killed them. They also led

groups of Jewish fighters into combat against the Wehrmacht.

Batalion

centers her book on one such group of exceptional women, some as young as 15,

all part of the armed underground Jewish resistance that operated in more than

90 Eastern European ghettos, from Vilna to Krakow. Knowing that there would be

no mercy in capture, only torture and a brutal death, the women bribed

executioners; smuggled pistols, grenades and cash inside teddy bears, handbags

and loaves of bread; helped hundreds of comrades to escape; and seduced Nazis

with wine and whiskey before killing them with efficient stealth.

There were

uprisings in at least nine cities, including Warsaw and Vilna — sustained by

the labyrinth of underground bunkers hand-dug by women, together with their

attacks on the electrical grid. And in part thanks to such acts of female

heroism, armed Jewish resistance broke out in Auschwitz and other death camps.

In all, 30,000 Jews joined partisan units in European forests, a significant

number of them women, despite the rough treatment (including rape) they often

received at the hands of male comrades.

Why,

Batalion wonders, had she not heard these women’s stories before? She stumbled

across them only by chance on the dustier shelves of London’s British Library.

The problem she then confronted in writing this book, which pulses with both

rage and pride, was choosing which women to include and which to leave out. Her

desire to pay tribute to as many as possible is understandable, but a simpler

narrative with fewer subjects might have been even more powerful.

One

story that definitely needed to be told is that of Vitka Kempner, a partisan

leader in Vilna, who had escaped through the bathroom window of her small

town’s synagogue to command fighters on the front line. Perhaps the standout

woman here, though, is the hugely appealing Renia Kukielka, whom Batalion

describes as “neither an idealist nor a revolutionary but a savvy, middle-class

girl who happened to find herself in a sudden and unrelenting nightmare.”

In

September 1939, when the Germans came to the Polish town of Chmielnik and

burned or shot a quarter of its people, Renia saw how only one Jewish boy tried

to confront them. Outraged, she vowed to join the resistance. She went on to

lose her family, her home, her friends and her money, but never her iron will.

Although not physically strong, she spied on the Nazis, smuggled weapons into

the ghettos and crossed heavily patrolled borders. When tortured by the Gestapo

to the brink of death, she remained defiant.

Of

course, Jewish men in the resistance performed heroic feats as well, but

because of the women’s ability to blend into the background they were often

assigned more daring roles. In the larger context of the war, their victories

were small and their sacrifices great. But the spirit of their resistance was,

as Batalion rightly notes, “colossal compared with the Holocaust narrative I’d

grown up with.”

The

‘Ghetto Girls’ Who Fought the Nazis With Weapons and Wiles. By Sonia Purnell.

The New York Times, April 6, 2021