Frau N. and her family hailed from a village in Franconia, in southern Germany. Her father was known as a Braucher, a person with certain healing powers. As much as locals relied on those who possessed such powers, communities like Frau N.’s often regarded healers with ambivalence, even mistrust. After all, might not someone able to use magic to take sickness away also be able to bring it? When Frau N.’s father died a difficult death, many of their neighbors were confirmed in their suspicion that he had been in league with sinister powers, and now the community adopted this unease toward Frau N. herself. She was also said to hold herself aloof, generally “swimming against the stream,” and orienting herself too much toward “the better sort.”

Every moment in time contains an unfathomably vast, kaleidoscopic array of variables that influence the direction and character of historical change in entirely unpredictable ways. It is a truism, in that sense, that every historical moment is unique. But the immediate post–World War II period was unique in a more radical way. That war still stuns us into silence. The scope of the disaster Nazi Germany unleashed on the world, so overwhelming as to defy understanding, recalibrated everything.3 In its capacity to make a mockery both of ordinary, everyday forms of knowledge and of expert wisdom, the war posed an anthropological shock—a shock to humanity as such—casting the basic knowability of the world into doubt. The ingenuity for destruction and cruelty demonstrated in World War II upended much that had seemed apparent or graspable about human behavior, inspiring the work of social scientists for decades to come. The very means by which the war was fought—genocide, massacres of civilians, mass population transfers, death squads and death camps, medical torture, mass rapes, mass starvation of prisoners of war, aerial bombardment, atomic weapons—obliterated taken-for-granted distinctions not only between soldier and civilian, home and battlefront, but also between the real and the incomprehensible. Who could have believed, before the Nazis created them, industrial complexes designed for no other purpose than the production and destruction of corpses?

When the twentieth century began, airplanes had not yet been invented. Few could have envisioned back then that within decades whole cities could be flattened from the air. Few could have imagined that a single bomb could destroy all life in a city and vaporize human bodies, leaving behind only ghostly traces of formerly living beings—or that people could be left “neither dead nor alive,” as took place at Hiroshima, “like walking ghosts.'' Science fiction became science reality. German philosopher and physician Karl Jaspers, who had opposed the Nazis, hoped to redeem science after the war, in the aftermath of the atomic bomb and Nazi medical experimentation. But even he admitted in 1950 that the “human condition throughout the millennia appears relatively stable in comparison with the impetuous movement that has now caught up mankind as a result of science and technology, and is driving it no one knows where.

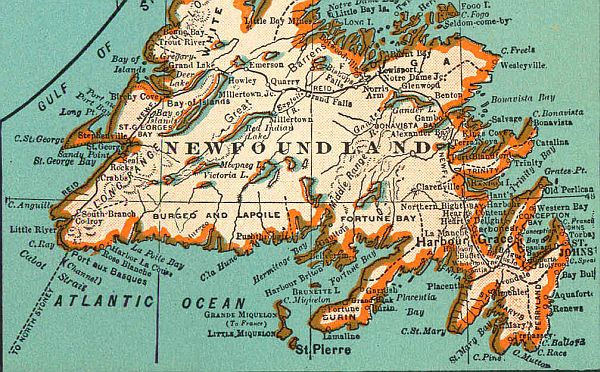

In defeated Germany, the problem of how to know the world was especially grave. The country itself did not even survive the war as an intact state, if a “state” means a sovereign entity with its own government, bureaucracy, and army, its own national economy and treaties and trade agreements. Germany no longer had the right to issue currency or even put up street signs Many traditional sites of authority—the military, the press, universities, the medical establishment—were deeply morally compromised or had been abolished by the Allied armies now occupying the country. The British, French, Soviets, and Americans carved up former Germany into four military occupation zones. The British and Americans merged their zones to create Bizonia, taking effect in January 1947. When the French joined them in 1949, Trizonia was born. The place even had an unofficial national anthem, “We Are the Natives of Trizonia”—a big hit at carnival time, since, like the German government and army, the German national anthem had also been banned. The Allies had talked extensively about dismantling the country’s industrial apparatus altogether, of closing down its mines and crippling its heavy industry, the source of its outsized military capacity. Germany, it was felt, could safely make clocks and toys and beer but not guns.

A general sense of indeterminacy hung over former Germany—and not just because its government had been decapitated, its powerful economy reduced to barter, its administration of public life controlled almost completely by foreign armies. Things people felt even more directly in their daily lives had all changed. Words and ideas, symbols and forms of greeting, even gestures that Germans freely used one day became taboo the next. Almost literally, the ground had shifted beneath everyone’s feet: in summer 1945, the Allies conferenced at Potsdam and agreed to redraw the map of Europe, stripping Germany of its territories east of the Oder and Neisse Rivers. In the ensuing whirlwind, between twelve and fourteen million Germans from various parts of Eastern Europe, some from communities that had existed since the Middle Ages, fled or were expelled, sometimes with great violence, from their towns and villages, and forced onto the roads. Will-Erich Peuckert, a folklorist, fled his native Silesia as a refugee. After the collapse of his country and his experience of flight, he found, “rational and causal thinking” were “no longer sufficient” to do his work as a scholar. He wondered whether this was because “our empire shattered and we stood mired in darkness, and nothing mattered anymore but just to harvest the grain.”

Millions were dead. Millions were missing and lost, never to return. Millions more remained imprisoned in POW camps all over the world. Millions had lost everything for a cause few could even seem to remember having supported. “Suddenly, we had to recognize,” recalled one man, “that everything we had done, often with great enthusiasm or out of a sense of duty—everything had been in vain.” Defeat and occupation and loss only compounded the need for answers. What had caused defeat? Who was to blame?

Social alienation and dislocation had become increasingly acute even before the war ended. In 1945, a report from the SD (the Sicherheitsdienst, the intelligence division of the Schutzstaffel, or SS) described feelings among the people “of mourning, despondency, bitterness, and a rising fury,” growing out of the “deepest disappointment for having misplaced one’s trust.” Such feelings were most pronounced, the report observed, “among those who have known nothing in this war but sacrifice and work.” By the war’s last months, Germans were fighting not only the Allied armies on their own soil but sometimes also each other. Some 300,000 or more non-Jewish Germans were put to death by the regime for treason, deserting the front lines, or showing signs of defeatism. Those who chose to leave the fight sometimes wound up hanging from the end of a rope with a sign around their necks pronouncing them cowards. Such acts of “local justice,” especially those meted out in small localities and urban neighborhoods, could hardly have been forgotten after the war, even if the resentments found no ready outlet.

Imagine living in a small town where your family doctor after the war is the same one who had recommended to the Nazi state that you be sterilized. Such scores could never be settled; such losses would go unredeemed. For many people, daily life was blighted by fraud and betrayal. Lying awake at night, people wondered what had become of their loved ones who vanished during the war. Some remembered seeing their Jewish neighbors carried away, and even if they did not fully comprehend what was happening then, they did later. Some families had adopted children during the war; orphans, they were told, maybe from Poland or Czechoslovakia. But surely some asked themselves, in a dark moment, who their child’s parents had been and what happened to them. During the war, people bought goods at open-air urban markets, items that had been stolen from Jews expelled to their deaths in Eastern Europe—tableware, books, coats, furniture. Germans ate and drank from china and glassware that had belonged to their neighbors and wore their clothing and sat at their dinner tables.

German is famous for its expressive vocabulary. Schicksalsgemeinschaft was a term used during the war to describe a community supposedly bound together by a shared experience of fate. Consensus among historians now holds that it was more an invention of Nazi propaganda than anything else.Certainly after 1945, German society evinced nothing like a coherent sense of communal and mutual experience, but rather shattered trust and dissolved moral bonds. In the Third Reich, denunciation had been a way of life. Citizens were encouraged to betray to the state anyone whom they suspected of the slightest disloyalty, sending many to concentration camps and often to their deaths. A person could be reported to the Gestapo for something as seemingly minor as listening to foreign radio. The memory of these experiences, for betrayer and betrayed, did not quickly dissipate. Alexander Mitscherlich, a psychiatrist who would later become one of the Federal Republic’s most prominent and respected social critics, described a “chill” that had “befallen the relationships of men among one another”—one that defied understanding. It was “on a cosmic scale,” he wrote, “like a shift in the climate.” A 1949 public opinion poll asked Germans whether most people could be trusted. Nine out of ten said no.

A great deal of what we know about the world comes to us secondhand, from parents and friends, teachers and the media; we take much of it on faith. For example, as the historian of science Steven Shapin says, we might “know” the composition of DNA without ever having independently verified it. In this sense, knowledge and trust are linked. “Knowing things” requires trusting other people as mutual witnesses to a shared reality, and trusting in the institutions that supply information that shapes everyday existence. Society itself could be reasonably described as nothing more or less than a system of commonly held beliefs about how the world works, beliefs that undergird and lend sense and continuity to our daily lives. Yet trust is never a given, never axiomatic: it is historically specific, constituted in different ways under varying circumstances.

In Germany after World War II, even the most basic facts of daily life could not always be easily or definitively substantiated. Up to 1948 at least, the black market reigned, and food was often found to be adulterated. Was this coffee or chicory? Flour or starch? Down to the simplest questions, things were not quite what they seemed. For years after the war, there were official documents that still referenced the “German Reich,” or whose authors appeared unsure about whether pieces of Germany ceded to Poland still belonged to the “empire.” Moral confusion produced a desire to “treat facts as if they were mere opinions.” And, as the novelist W. G. Sebald reflected, a “tacit agreement, equally binding on everyone,” made discussing “the true state of material and moral ruin in which the country found itself” quite simply taboo.

Some basic truths were too toxic even to acknowledge, let alone discuss. The philosopher Hans Jonas escaped Nazi Germany as a young man in 1933 and went to Palestine, where he joined the Jewish Brigade. His mother stayed behind in Mönchengladbach, the family’s Rhineland hometown. She was murdered at Auschwitz. When Jonas came back in 1945, he visited his family home on Mozartstraße. He spoke to the new owner. “And how’s your mother?” the man asked. Jonas said she had been killed. “Killed? Who would have killed her?” asked the man, dubious. “People don’t do that to an old lady.” “She was killed at Auschwitz,” Jonas told the man. “No, that can’t be true,” the man replied. “Come on, now! You mustn’t believe everything you hear!” He put his arm around Jonas. “But what you’re saying about killing and gas chambers—those are just atrocity stories.” Then the man saw Jonas looking at the beautiful desk that had belonged to his father. “Do you want it? Do you want to take it with you?” Revolted by the man, Jonas said no and quickly left.

Some people found their wartime experiences so overwhelming that they could not connect their own thoughts and feelings even to those with whom they had shared them. The novelist Hans Erich Nossack witnessed the Allied firebombing of Hamburg, his home city, in 1943. Afterward, he found that “people who lived together in the same house and ate at the same table breathed the air of completely separate worlds.… They spoke the same language, but what they meant by their words were entirely different realities.” Heinrich Böll’s 1953 novel And Never Said a Word features a character named Fred Bogner who can hardly relate to anyone from his prewar, pre-soldier life. He is so mortified by his poverty and inability to cope that he has left the home he shared with his wife, Käte, and their children. He spends his days drinking and visiting cemeteries, finding comfort among the dead, and attending funeral masses for people he never knew. Sometimes he is invited out to lunch by their families, whom he finds easier to talk to than almost anyone he knows.

* * *

When World War II came to an end, Germany lay in ruins. Entire cities had been shattered by bombs and artillery, expanses of land left bare where every tree had been cut down for fuel, parts of the country practically erased. More lasting than the physical devastation, however, and even greater than the stigma of defeat and occupation, was the moral ruination. Germany in 1945 was a global pariah, responsible for crimes that beggared imagination. Yet within a short time, occupied Trizonia became the Federal Republic of Germany, or West Germany. It was integrated into the Cold War’s Western alliance, had an economy unrivaled in Europe, and was seeing its bomb-flattened cities rapidly rebuilt for a good life of consumerist plenty. History, which is often thought to move glacially, has in its annals not many shifts of fortune as sudden as this. And in this dramatic transformation lie questions at once rich and unsettling.

For quite some time, scholars wrote the Federal Republic’s history as a success story. They described its fundamental conservatism, but also its stability, and the establishment of a constitutional republic under the cautious leadership of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. Historians emphasized the “economic miracle” of the 1950s and ’60s and highlighted the combination of full-bore capitalist enterprise and a powerful social welfare state—the “social market economy”—that produced nearly unparalleled consumer affluence for West German citizens. The historiography accentuated the country’s integration into the Cold War West, telling a story about the hard work of rebuilding and the gradual achievement of economic power and “normalization” after the devastations of war. This narrative remains implicit in accounts of the immediate postwar period. “With every passing year,” one historian writes, “German lives inched further toward … the stability and predictability of a civilian life.”

It is an appealing story. And it’s one a lot of West Germans wanted to see themselves in after the war, after the trauma of defeat and foreign occupation. A new, national self-image was under development in the Federal Republic’s early decades, one based not on fantasies of racial superiority and indomitable military prowess but on technical skill, discipline, and hard work. That narrative was reassuring, too, no doubt, because its concreteness and orderliness and reasonableness contrasted so sharply with the magical thinking of the Third Reich. Gone was its myth-ridden leader cult, its blood-and-soil mysticism.

Such master narratives offer coherence, but they also smooth out the rough spots. As insightful critics have noted, the early Federal Republic was a little like a film noir—a genre popularized in the Hollywood of the 1930s and ’40s but rooted aesthetically in German expressionism. Noir plays with depths and surfaces, shadow and light, emphasizing that what we see is not necessarily all there is to know, and that a shiny veneer can conceal something considerably less appealing. Just below the surface of West Germany, moving murkily in the near depths, was the ever-present memory of the war and crimes that had led to the state’s creation in the first place. What’s more, the surreally abrupt shift that had taken place—from murderous dictatorship to democracy, from wholesale theft and mass death to “normal life”—relied extensively on the integration of Nazi perpetrators into society. Largely shielded from prosecution, many of them found promising new métiers amidst changed economic and political realities. Many professions, from government, law, and police to medicine and education, remained packed with former Nazis.

The dissonant contradictions of that transition—such as it was—cannot be accounted for in the bland terms of unemployment statistics and GDP. Appreciating the noirish qualities of early West German history requires an openness to other realities. As one scholar notes, the literature of this period speaks of “magical eyeglasses, limping prophets, martial toys, games and sports, powerful engines, robots and hydrogen bombs, abortion, suicide, genocide and the death of God.” Such artifacts fit together only incongruously, brandishing jagged edges. Period newspapers reveal similarly sharp juxtapositions: an advertisement for laundry soap starring a perfectly coiffured, wasp-waisted hausfrau wearing a crisp, white apron appears alongside a story about unmarked mass graves just discovered in a local park.

On one level, it seemed to even the keenest observers after World War II that Germans remained remarkably unchanged by their recent history. Most famous of these commentators was the German-Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt, who fled her homeland in 1933 but returned from her new home in the United States to visit in 1949. The country seemed to go on as though nothing much had happened. Nowhere else in devastated Europe was the nightmare of the recent years “less felt and less talked about than in Germany,” Arendt wrote. She described an indifferent, emotionless population inscrutably sending each other postcards of a destroyed and vanished past, of historic sights and national treasures that bombs had blown away. She wondered whether postwar German “heartlessness” signified “a half-conscious refusal to yield to grief or a genuine inability to feel.” It was as though, after the war ended, Germans just dusted themselves off, began picking up the rubble piece by piece, and started rebuilding. What, if anything, most people felt or thought about what had just happened—the collapse of their country in defeat, its occupation by foreign armies, their participation or complicity in the most heinous crimes—these remained largely opaque, shrouded in silence. While Germans did talk, obsessively, about their own losses in the war, there were many other things they simply did not discuss, at least not publicly: allegiances to the former regime, participation in antisemitic persecution and looting, genocide, war crimes.

The German philosopher Hermann Lübbe famously (and controversially) argued that silence about Nazi crimes was crucial to making a new country out of an old one, a “social-psychological and politically necessary medium to change our postwar population into the citizenry of the Federal Republic of Germany.” Silence was what allowed a society riven by the knowledge that it contained all sorts of people—those who had worked to support the Nazis, those who had actively opposed them, and everyone in between—to rebuild a country together. People kept quiet for the sake of reintegration.

Looking through the prism of the mostly unremembered scenes and events this book describes, one perceives things that have often remained occluded: fears of spiritual defilement, toxic mistrust, and a malaise that permeated daily life. Beneath the affectless behavior that Arendt observed lay anxieties that didn’t even have names, and these churned away throughout the 1950s against the backdrop of consumerist forgetfulness. In the immediate shadow of the Holocaust, defeat in World War II, and the tension of the early Cold War decades, West Germans quietly nursed various wounds and pricks of conscience. Corruption laced many relationships, and a fundamental estrangement among people lingered on, even as reconstruction proceeded and the roads were repaved and the shops and schools and squares again bustled with life and enterprise. The scenes this book describes offer a view into that otherwise inaccessible existential and spiritual territory. They are a portal onto a demon-haunted land.

Introduction. A Demon-Haunted Land : Witches, Wonder Doctors, and the Ghosts of the Past in Post–WWII Germany. By Monica Black, November 2020.

Metropolitan Books

And in western Germany, insistent end-of-days prophecies continued to swirl. But then amidst them, a very different kind of news suddenly took wing. In March 1949—the same month, and indeed on practically the very day that popular rumor had slated for the end of time—in the small Westphalian city of Herford, a young boy who was unable to stand on his own received a visit from a curious stranger.

Though no one, not even the boy’s parents, quite understood just what had happened, after meeting this man their boy got up out of bed for the first time in months and, slowly and hesitantly, began to walk.

The impact of this single occurrence would be explosive, like a bolt out of the blue. Soon, tens of thousands would stand in the rain for days at a time just to catch a glimpse of the apparent author of the boy’s recovery: an obscure, long-haired healer dressed in inky shades of blue and black. Cure-seekers would prostrate themselves in supplication before him, or try to buy his bathwater. Some believed he could raise the dead.

He would become the first German celebrity of the postwar era, his image splashed across newspapers and tabloids from one end of the country to the other. Paparazzi, police, and eventually a documentary film crew would trail him everywhere he went. Some called him miracle doctor (Wunderdoktor), miracle healer (Wunder heiler), wonder worker (Wundertäter), cure bringer (Heilspender), even savior (Heiland).

Others called him a charlatan, a demon, a sexual deviant, a dangerous lunatic, an inciter of mass hysteria. To yet others, he was “the Good Son of God.” His friends called him Gustav. His name was Bruno Bernhard Gröning.

The headline of one of the first national news stories about him gives us some idea of the stakes as people perceived them in that moment: God Sent Me: The Truth About the “Messiah of Herford.” Over the following months, Gröning was interviewed on the radio and featured on newsreels. Mere rumors that he might show up somewhere jammed city traffic for hours. High-ranking government officials extolled his talents before enormous crowds. Aristocrats and sports and movie stars befriended him.

Who was this Wunderdoktor Gröning, and what did he have to say? What made hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people read about him, listen to him, pilgrimage long distances in the hopes of meeting him? In part, the answer is that he was seen as the instrument of something powerfully providential.

Herford lay within the geographic scope of Alfred Dieck’s study of apocalyptic rumors, which had chronicled dire predictions of the imminent end of the world and terrifying prophecies of planet-smothering snows. Now, the chaos had yielded to something unexpected: healing. For those inclined to look for signs, one had arrived.

Still, exactly what that sign meant wasn’t easy to say. Like millions of his countrymen, Bruno Gröning was a former soldier and POW. He had also been a Nazi Party member. He didn’t have much in the way of what you might call a philosophy, at least not initially. He didn’t preach. He didn’t write books or found a church. When he spoke, it was mostly in hazy, elliptical aphorisms, which sometimes touched on vaguely spiritual themes but more often than not circled back to the topic of good versus evil.

He also did not really have a defined technique for curing the sick, at least not one that could be plainly articulated in words. It was not even clear to anyone exactly what he was healing, or how. His method, such as it was, mostly consisted of being near people who were ill and sometimes training his gaze on them. And that didn’t always work: the young boy whose cure became the origin story of this whole affair was back in bed again only a few weeks later. But often enough, the healing seemed to hold.

Many sources convey Gröning’s powerful impact on people, and many people testified to his cures. But from history’s standpoint, the real story is not him at all. It’s them: the huge crowds that surged up around him everywhere he went; the hopes, fears, and fantasies they projected onto him; and the vast drama of emotions—usually kept in tight check—that played out in those crowds.

The interaction between postwar German society and Bruno Gröning matters because in some very real sense, that society invented him to cure what ailed it—not just disease and injury, but forms of disquiet and damage that were much harder to see. This is a story about sickness and healing, and about the search for redemption. But first, it’s a story about a family and a stranger in town.

*

Helmut was away at the war then, serving as an engineer in the Panzerwaffe, the Wehrmacht’s armored division. Later, he spent some time in a POW camp, returning home to Herford in June 1945.On the way home—whether by train or on foot—he would have seen mile after mile of ruins, the broken remains of a former life: mangled bridges, burned-out buildings, gutted machinery, and roadside graves with homemade crosses.

He probably had few illusions that the destruction had been contained at the front, especially since the front had come home to Germany. Letters from home, too, might have mentioned the bombs and the fighting and the endless refugee caravans. But hearing about and seeing are not the same.

Back home in Herford, Helmut found his boy in a miserable state. He had the casts cut off immediately. Still, Dieter’s condition worsened. Helmut took his son to the university clinic in Münster, 70 miles away. The diagnosis was vague but grim: progressive muscular atrophy. This assessment was confirmed in a pediatric clinic and by ten other “doctors and professors,” but none had any treatment to offer.

There is nothing we can do, the doctors reportedly told the family. Over the winter of 1948–49, when he was nine, Dieter took to his bed and did not get up for ten weeks. Nothing warmed his ice-cold legs—not blankets, not hot water bottles, not massages. When he tried to stand, Helmut later said, he “snapped forward at the waist like a pocket knife.”

Anneliese’s father said he knew someone who knew a healer. The man had just helped a woman paralyzed for more than five years walk again. Maybe he could help the boy?

One day, an acquaintance brought Bruno Gröning to Herford by car. The relationship between him and the Hülsmanns got a fair amount of legal scrutiny later on, and the historical record betrays some confusion about the date, but it seems to have been March 14 or 15. The calendar promised imminent springtime, but Herford was gloomy, wet, and windy, and the coming days would be colder.

Here, in the Ravensburg basin, between the Teutoburg Forest to the west and the low-slung hill country of the Weser River to the northeast, the late-winter sky can turn pitiless and leaden against a landscape of alternating woods and meadows, with towns and farms and villages unfurling into the distance as far as the eye can see. In rainy weather, mist can veil the black-brown earth, merging landscape and sunless sky into a single, inscrutable shade the color of wet wool.

The Hülsmanns made their home in a handsome, whitewashed villa on Wilhelmsplatz. Once, the square had boasted a statue—though not, as one might expect from its name, an homage to Emperor Wilhelm. The subject was a much older hero: the 8th-century rebel Saxon leader Widukind. After fighting the armies of the Frankish king Charlemagne for more than a decade, Widukind was defeated in 785 CE and converted to Christianity.

Legend has it that the Saxon, whose name meant “child of the forest,” rode to his baptism on a black horse. Whether this was an act of defiance in the face of a forced conversion or Widukind’s announcement of the spiritual death of his former pagan self, no one really knows. In lore, certainly, it is a redemption story: a “child of the forest”—meaning not only a pagan, in the thinking of his times, but a child of the Devil—became a Christian, a child of God.

Many Nazis, though, saw Widukind not only as a folk hero but as an ideological exemplar, a native Germanic resister against the militant Christianity of Charlemagne, whose Frankish Empire had destroyed local, pre-Christian gods and usurped the Germanic peoples’ historic freedoms. In the Westphalian countryside of the 1940s and ’50s, horse heads still decorated houses. Traditionally, it was said that Widukind’s spirit lived on in them, protecting homes and promoting health.

From 1899 until 1942, Widukind’s statue stood just steps away from the Hülsmanns’ front door. But during the war it was toppled and, like thousands of church bells and other treasures, melted down to make guns.If on reaching the Hülsmanns’ doorstep on that late-winter day Gröning had turned slightly westward, he would have seen not Widukind forged in triumphal bronze, astride a stallion and wearing a winged helmet, but a naked granite stump.

No documents allow us to reconstruct Gröning’s arrival in Herford in any detail. But photographs from the time let us imagine him against a gray afternoon’s backdrop, standing before the Hülsmanns’ tasteful home, maybe turned to take in that violated monument. He was not tall. His frame, though athletic, could tend toward gauntness. In pictures, his pushed-up shirtsleeves reveal strong, ropy arms.

His hair—wiry, dark, and quite long for the time and place—would often be a subject of interest (and humor) in the press. People commented again and again on his intensely blue eyes, which bulged slightly. His face was weathered, even haggard. He had hands accustomed to work, the ngers stained with nicotine.

He dressed simply, seemingly always in dark clothing. He spoke simply, too, many would say. In his pockets, he sometimes carried little tinfoil balls with bits of his hair and fingernails in them. And he had an unmistakable goiter that, he would claim, allowed him to absorb his patients’ sick-making energies.

Anneliese Hülsmann was a slim woman who dressed in a plain fashion, her hair tied back modestly. Helmut, for his part, was regarded by some as a bit crass—the sort to chew a fat cigar while talking too loudly at the same time. Still, given Helmut’s occupation as an engineer, the Hülsmanns would have belonged to prosperous Herford’s professional middle class.

Gröning’s origins, on the other hand, were working class. He was not especially comfortable speaking textbook German and by some accounts preferred the dialect of his home region. He chain-smoked American cigarettes—Chesterfields—and drank cup after cup of strong, black coffee. We don’t know exactly what happened after he arrived at the Hülsmann home, whether the group first sat together to drink coffee and smoke, to exchange pleasantries or misgivings. At some point, though, Gröning went in to see Dieter.

Scores of people would later attest to the extraordinary abilities of this long-haired, raw-boned refugee. How he seemed to possess the power to know what was going wrong in a sick person’s body, and how to talk to those who were ill. How, as soon as he appeared, everything changed. You could hear a pin drop, it was said.

Gröning’s gaze would travel slowly from one person to the next. He would stand perfectly still and perfectly silent with his hands in his pockets and tell the afflicted not to think too much about being ill. Their fingers would begin to tremble, and they felt things happening in other parts of their bodies as well. He would take the foil out of a pack of cigarettes and work it into a little ball, and then give these foil balls to the sick and tell them to hold the ball in their hands and focus on it until they felt better.

He had a habit, too, of repeating strange rhyming formulas, like: “it could also go down the other way around” (Umgekehrt ist auch was wert). Patients said they felt a warm current flowing through their bodies or an unaccustomed prickling sensation under his gaze.His brother Georg said Bruno could stop toothaches, just by concentrating on the hurting tooth.

What happened when Gröning first met Dieter Hülsmann would be told and retold for a long time after: initially in rumors, gossip, jokes, letters, and casual conversation; then via newspapers, magazines, sermons, speeches, films, pamphlets, and books; then in accusations, denunciations, exposés, police and psychiatric reports, witness statements, court briefs, legislative inquiries, and academic journals and eventually—much, much later—on websites in dozens of languages.

Within an hour of encountering the healer, the boy suddenly had feeling back in his legs, which Anneliese said “almost never happened anymore.” There was a burning sensation in his legs and back. His cold limbs had suddenly warmed. The next morning, however unsteadily or hesitantly, Dieter, who had spent much of that bleak postwar winter in bed, got up and walked.

Over the coming days, his condition improved further. At first, Helmut said, he “did not quite believe” what was happening. Yet soon he was convinced that his son was cured.After two weeks, Anneliese recalled, “my boy could move freely and walk without any help around the house and outside.” He still could not climb stairs without help, and he stood on tiptoe rather than with his feet fully on the ground.

But his father told the press that he was sure that this too would pass.By then, the Hülsmann family had invited Gröning to come and live with them. And he had accepted.

It was not long before the villa at number 7 Wilhelmsplatz would be inundated with pilgrims, as news of Dieter’s cure spread far beyond Herford, and then even beyond western Germany. Thousands would flood this small city, coming just in the hopes of seeing the black-clad Gröning or speaking with him for a moment, seeking relief for maladies of every imaginable kind. He would meet them in the Hülsmanns’ parlor or on their front lawn. From time to time, especially late at night, he would appear on the villa’s upper balcony to dispense cures to the crowds gathering below.

No one quite knew how they worked, but what they heard was wondrous: that people who had been paralyzed, or sick in bed for years, would suddenly stand up and walk. That adults and children with trouble speaking could talk without hesitation or constraint. That stiff and damaged limbs and fingers became supple, and lifelong pain vanished. That the deaf could hear and the blind see.

What brought clarity to the surging chaos of 1949, in short, was not the end of time, as rumor had predicted for months. Instead, it was a tale of miracles, one that almost anyone could recognize. As cure-seekers began trickling into Herford that spring, Wilhelmsplatz became a spiritual destination.

The world had not drowned in iniquity; there had been no apocalyptic fire, no death rays to split the earth in two. Instead, there was healing. There was redemption. Soon, what was already coming to be known as “the miracle of Herford” would grip the nation.

Excerpted from Demon-Haunted Land: Witches, Wonder Doctors, and the Ghosts of the Past in Post–WWII Germany by Monica Black. Published by Metropolitan Books, an imprint of Henry Holt and Company, 2020.

The Mysterious Celebrity Miracle Worker of Postwar Germany : Who—and What—Was Bruno Bernhard Gröning? By Monica Black. LitHub, November 17, 2020.

Monica Black is Associate Professor of History at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Her first book, Death in Berlin: From Weimar to Divided Germany, won the Wiener Library Ernst Fraenkel and Hans Rosenberg Prizes. She is the editor-in-chief of the journal Central European History.

On August 31 President Trump told Fox News host Laura Ingraham that people in “dark shadows” were controlling Joe Biden. When pressed by Ingraham, Trump elaborated, “We had somebody get on a plane from a certain city this weekend and in the plane it was almost completely loaded with thugs wearing these dark uniforms, black uniforms with gear and this and that.”

When Democracy Ails, Magic Thrives. By Samuel Clowes Huneke. Boston Review , October 29, 2020