Our investments marked the relationship as special, and the seriousness of our plan became evidence of the seriousness of our feelings, testaments that our tie went beyond vanity and was more than infatuation. In this, I remain sure, we were not wrong. Nothing then or since has shaken my belief that no matter how excruciatingly immature we might have been, at their core the feelings were both rare and very real.

Beacon Press

“I don’t want to date or even make out with you. Because that would be weird,” the comic continues across a series of panels, but the narrator does want:

the other person to think they are awesome

to spend a lot of time hanging out

Facebook chats after midnight

to email weird blog links

to swap favorite books

to @reply to each other’s tweets

to walk to their favorite food trucks

to find the best hole-in-the-wall cafes together

to have inside jokes

but all “in a platonic way, of course.”

I want to be close to you and special to you, the way you are to me, but I do not want to be sexual with you, this comic says. I want to be emotionally intimate with you and I want to be in love with you, but not in that way. Just as saying woman doctor implies that a doctor by default is male, clarifying this feeling as friend-love implies that love—the real thing, the romantic thing—is for sex. In truth, Sakugawa’s descriptions of platonic friend-love are similar to what many aces would call nonsexual romantic love.

Nonsexual romantic love sounds like an oxymoron. Almost all definitions of the feeling of romantic love—separate from the social role of married partners or romantic acts like saying “I love you”—fold in the sexual dimension. People might not be having sex, but wanting sex is the key to recognizing that feelings are romantic instead of platonic. Sexual desire is supposed to be the Rubicon that separates the two.

It’s not. Aces prove this. By definition, aces don’t experience sexual attraction and plenty are apathetic or averse to sex. Many still experience romantic attraction and use a romantic orientation (heteroromantic, pan-romantic, homoromantic, and so on) to signal the genders of the people they feel romantically toward and crush on.

Intuitively, it makes sense that people can experience romantic feelings without sexual ones, and few are confused when I define romantic orientation as separate from sexual orientation. The understanding breaks down once someone asks what it means to feel romantic love for someone if wanting to have sex with them isn’t the relevant yardstick. How is that different from loving a platonic best friend? Without sex involved, what is the difference people feel inside when they draw a line between the two types of love? What is romantic love without sexuality?

Once again, this isn’t a question only applicable to aces. Allosexuals (allos, for short) might feel infatuated with a new acquaintance or be more attached to their best friend than to any romantic partner, yet they can deny the possibility of romantic feeling because of the lack of sexual attraction. Allos can wave their hand and say, “There are people I want to sleep with, and I don’t want to sleep with you, so it’s only platonic.”

As convenient as it is that allos can use sexual desire to distinguish the categories, this is also a constricting way to evaluate the world, and allos can seem as bewildered by their feelings as aces. For them, emotional intimacy and excitement can be confusing or nonsensical if they don’t include sexual attraction. Many allos have shared with me their puzzlement at feeling like they were in love with friends despite no sexual attraction on either side. The writer Kim Brooks published a long essay in The Cut puzzling over how it could be that she has obsessive relationships with women despite being straight. Of her college roommate she writes, “the relationship was never sexual, but it was one of the most intimate of my young adulthood. We shared each other’s clothes and beds and boyfriends.”

Aces know that sex is not always the dividing line that determines whether a relationship is romantic. We take another look and say, “Maybe you’re in love with your friend even if you’re not sexually attracted to her.” Questions about the definition of romantic love are the starting point for aces to think about love and romance in unexpected ways, from new, explicit categories beyond friendship and romance to the opportunities (legal, social, and more) of a world where romantic love is not the type of love valued above all others. Asexuality destabilizes the way people think about relationships, starting with the belief that passionate bonds must always have sex at the root.

For 16-year-old Pauline Parker, June 22, 1954, was “the day of the happy event.” She wrote those words in neat script across the top of her diary entry, marking it as a much-wished-for occasion. “I felt very excited and ‘the night before Christmas-ish’ last night,” she wrote underneath. “I am about to rise!”

The happy event would take place as Pauline hoped, though the long-term consequences would not be what she intended. Later that afternoon, Pauline and her friend Juliet Hulme, age fifteen, took Pauline’s mother for a walk through Victoria Park in Christchurch, New Zealand. As the three went down a secluded path, Juliet dropped a stone. When Pauline’s mother bent down to pick it up, the two girls bludgeoned her to death with a brick inside a stocking, taking turns bludgeoning the woman to death and smashing her face almost beyond recognition.

The teenagers had met a couple of years before, when Juliet—beautiful, wealthy, and from a high-class British family—was then new to the country. Pauline was less comely and less moneyed; her father ran a fish store and her mother a boardinghouse. The two became inseparable, often lost in their own rich fantasy world. The bond was threatened when Juliet’s parents decided to send her to live with relatives in South Africa. Pauline could come along if Pauline’s mother would allow it, but everyone knew that this suggestion would never be approved. For the girls, the only way forward seemed to be the brick and escaping to a new life in America.

From the murder to Heavenly Creatures, the Peter Jackson film it inspired, to the lasting fascination the case holds today, Pauline and Juliet have never been able to dispel the suspicion that they were having sex. Juliet has denied that the two were lesbians, but her denial means little in the eyes of a world that believes only specifically sexual love could inspire that type of mutual obsession. This belief—that platonic love is serene while intense, passionate, or obsessive feeling must be motivated by sex—is common. It does not track with reality.

If you don’t believe aces who say that passionate feelings can exist without any sexual desire, believe University of Utah psychologist Lisa Diamond, who says the same thing. (Diamond refers to the feeling of “infatuation and emotional attachment” as “romantic love,” so I will too here.) Diamond theorizes that the two can be separate because they serve different purposes. Sexual desire tricks us into spreading our genes, while romantic love exists to make us feel kindly toward someone and willing to cooperate for long enough to raise those exquisitely helpless creatures known as babies. Romantic love can be more expansive than sexual attraction because heterosexual sexual attraction, while usually necessary for producing kids, is not required for successful co-parenting. To use ace lingo, sexual attraction and romantic attraction don’t need to line up.

Diamond first noticed this conflation of passion and sex when interviewing women about how they became aware of their sexual attraction to other women. “So many [women] would tell these stories about having a really strong emotional bond to female friends when they were younger, and they’d be like, ‘So I guess this was an early sign,’” she tells me. Close female friendships do frequently use affectionate, quasi-romantic language that can confuse burgeoning sexual desires. Sometimes though, the story can be more complicated, and Diamond, an expert in sexual fluidity, began questioning whether passion must always equal secretly sexual.

If sexual desire were necessary for romantic love, kids who haven’t gone through puberty wouldn’t have crushes. Many do. Surveys show that children, including ones too young to understand partnered sex, frequently develop serious attachments. I had elementary school crushes and so did many of my allo friends. Adults have gone through puberty but their sexual desires don’t always dictate their emotional ones either. In one study Diamond references, 61 percent of women and 35 percent of men said they had experienced infatuation and romantic love without any desire for sex.

It is already taken for granted that sexual desire doesn’t need to include infatuation or caring. one-night stands and fuck-buddy arrangements are all explicitly sexual and explicitly non-romantic. The opposite conclusion—that for some, infatuation never included and never turns into sexual desire—is harder for people to accept, at least in the West. The story is different elsewhere. Historical reports from cultures in Guatemala, Samoa, and Melanesia describe how these close, nonsexual relationships were acknowledged. Sometimes honored with ceremonies such as ring exchanges, these relationships were considered a middle ground between friendship and romance and were often simply called “romantic friendship,” Diamond tells me.

In these cultures, marriage was often more of an economic partnership than a love match. The marital and sexual bond was not automatically assumed to be the most important emotional relationship, unlike in current Western culture. Romantic friendships were not considered a threat to marriage and it was easier for people to believe that a nonsexual relationship could be as ardent as a sexual one. Romantic friendships were passionate on their own terms because passion is possible in many types of relationships.

Excerpted from Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex by Angela Chen (Beacon Press, 2020).

Let’s

Rethink How We Talk About Love, Intimacy, and the Absence of Desire. By Angela

Chen. LitHub, September 18, 2020.

When we think of what makes a person or group of people “queer,” a common understanding is their having a sexual orientation and/or gender identity that separates them from the heterosexual, cisgender majority. But what about asexuals—those folks who don’t experience sexual attraction toward others? Are “aces” part of the queer community, too? In this month’s episode of Outward, Slate’s LGBTQ podcast, the crew tackles that question with Angela Chen, a journalist and asexual activist who’s just written a book on the subject: Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex. A portion of the discussion is transcribed below. It has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Rumaan Alam: One of the subjects of your book is an artist named Lucid Brown, who describes coming across a letter to Dear Abby from an asexual reader. And they describe seeing this letter in the newspaper at age 13 and then stealing the newspaper from the dining room table. This felt really, really familiar to me as someone who was once a gay teen reading the tea leaves of the culture for some validation of the self. I’d love to hear you talk about the tension or the complication around understanding ace identity as fitting under the queer umbrella.

Angela Chen: I think that’s a delicate question. I have a line in the book that’s a little bit of a throwaway line, and maybe I should have elaborated on it more, where I say that today, overall, asexuality is accepted as part of the queer umbrella, of the broader LGBTQ+ umbrella, but it feels conditional in many ways. I think there is a discussion around whether people who are ace and heteroromantic—romantically attracted to the opposite gender—should be considered queer. I believe that aces are queer, but I wanted to point out that in some ways, this is not a simple question. I think that there is this understanding, this idea that because asexuality in many ways is invisible and invisibility gives you this form of protection, it feels like you don’t need to come out. It feels like if you’re on the street with your partner, many times, you are not going to be a target in the same way. In many ways, being asexual doesn’t require feeling like you need to hide yourself in the way that has been the case for the other identities in the queer umbrella.

And so I think that there is that discussion: Where does asexuality fit? What connects people in the queer community? What does that mean? There is also this question of resources and a feeling of scarcity. So every ace activist has always said, “We don’t want to take resources away from people who are trans or people who are homeless. It doesn’t seem like this competitive thing to us.” We’re not saying we’re the most oppressed, but we feel like we are in many ways outside of heteronormative, straight culture, and we want to build coalitions and we want to be part of that.

But despite that, I think many aces, especially heteroromantic aces, struggle with feeling queer enough. Almost every hetero ace I’ve spoken to has said, “Oh, I completely support all other hetero aces identifying as queer if they want, but I feel afraid because I feel like am I taking away from the struggle?” So I think these discussions around gatekeeping, what actually connects the community, are very, very much alive here. And also I want to mention, of course there are people who are ace and biromantic. There are people who are ace and nonbinary trans. So, the ace community itself is very diverse and there is a lot of cross-cutting identities.

Bryan Lowder: In the book you introduce the term “compulsory sexuality.” We know that the term “compulsory heterosexuality” comes from Adrienne Rich, but can you explain how this other term builds on that?*

Angela Chen : Absolutely. I think it’s just the idea that everyone who is “normal” wants sex and desires it. The example that I always think of is a person I interviewed, someone named Hunter, who grew up in this religious environment, and he is hetero. He is only attracted, romantically attracted to women. So he fulfills the compulsory hetero part of going through heterosexuality, but it was sexuality itself. Even though he’s attracted to women, he wasn’t super into sex, and that made him feel like there was something wrong with him. That everything he had been taught about how good sex was and how you were only an adult if you loved sex and how you’re only a real man if you loved sex, that really made him feel like he was broken.

I think that is an easy way to understand that. And there’s so many other examples, like low sexual desire is medicalized. The FDA is trying to sell and approve drugs for low sexual desire. And of course, that’s telling you that there’s something wrong with you. Or for women again, if you say that you’re not that into sex, oftentimes very well-meaning people will say, “Oh, you just need to free yourself from shame. You need to, like, be in touch with your true self and throw off the chains of patriarchy”—which is definitely true sometimes. But sometimes you’re just not that into sex and it doesn’t mean that there’s anything wrong with you or that your life is going to be worse if that’s not a source of pleasure for you.

Listen to the full conversation with Angela Chen on the podcast.

Slate, September 16, 2020.

We all

know that there’s an “A” in the LGBTQIA+ acronym, and no, it doesn’t stand for

“ally.” It stands for “asexual,” or ace, and it’s a branch of the queer

community that is too often ignored or even erased. Like all labels, it means

different things to different people, but on a most basic level it refers to

people who don’t experience sexual attraction. What does this mean? That’s what

writer and science journalist Angela Chen, who herself identifies as ace,

explores in her new book Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society,

and the Meaning of Sex (out now from Beacon Press).

In case

my job title of "sex and relationships reporter" isn't a clue, I'm a

sexual person. Since coming of age, I've thought about sex, watched sex (either

pornographic or simulated in mainstream media), talked about sex, written about

sex — and, as you can assume, had sex.

Mashable:

What inspired you to write Ace?

Chen :

In the

second episode, one of the first people to leave the sex cult talks about how

she reached out to someone who also left and she said something like, "I

reached out to her because I didn't know intellectually what I was looking at,

I knew how I felt." When I was watching this, I felt like that's such a

good metaphor for the experience of learning any kind of new lens. You know how

you felt — you have these confusing feelings that don't make sense. And then

once you have intellectual grounding, all of a sudden your life makes so much

more sense, or your feelings make so much more sense. I think that's really

powerful.

That

does make a lot of sense. Going back to what you said about Tumblr, the site

was definitely like that for me, too. People on Tumblr would describe what I

was feeling as a bisexual person. Do you think that's still the case for Tumblr

as a source of learning, or do you think the internet has moved on? I looked at

the asexual tag on TikTok today and there's over 200 million views. For teens

today, what resources do they have?

Tumblr,

TikTok, the internet remains a huge resource. There was a study where a huge

portion of people first learned about asexuality on Tumblr, and I think that

continues. But it's a bit of a double-edged sword. You learn so much on Tumblr

and TikTok and Twitter and because of that, asexuality is often considered to

be this kind of "internet orientation" in the same way that

everything that teen girls do is seen as stupid. Everything that has a huge

following on various corners of the internet is seen and dismissed as something

just for young people and not worthy of the mainstream. That's part of what I

wanted to do with the book — there's so much more about asexuality than in my

book, but I hope that asexuality will reach people who are not in these places.

While I was reading Ace, I felt a sort of kinship [as a bisexual]. In the broader LGBTQ community, I sometimes feel like I don't belong. With terms like gold star [lesbians or asexual], there's a certain wanting of being an archetypal example of what you "should" be. As the queer community is essentially counterculture, being counterculture to the counterculture is a weird place to be in. What are your thoughts on this? Is education like your book the answer to, say, a gay person not wanting to date someone who's bisexual, or someone who's aromantic [has no interest or desire for romance]?

Chen :

You're

right, there's so much gatekeeping in so many ways. Even in the queer

community, I think there's a lot of misconceptions and questions about whether

aces should be part of the queer community.

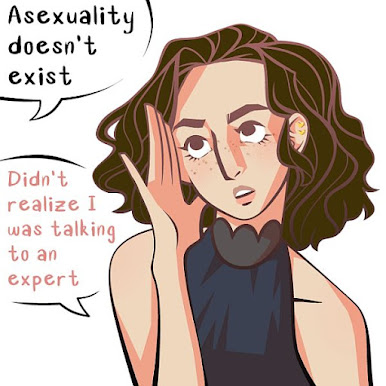

I don't have an easy answer. People will sometimes say to ace people, "What kinds of discrimination have you suffered? It's so easy being ace." There's these misconceptions about what the ace experience means from people who are allosexual and some other people who may be queer but not asexual. In the end, I think there's a lack of understanding about specific experiences.

Mashable :

In the book, you talk about your own personal history. Partway through, you mention not wanting to be honest about some of your experiences. How did it feel to share these details about your self-discovery in such a radically honest way?

Chen :

It made

me confront the extent to which I've internalized many forms of acephobia. Like

I write in the book, intellectually and morally I believe everything I write,

that being asexual is in no way inferior and all of that. But as I was writing

the book there were parts of me that were defensive — and of course that's part

of my personality, some of which has nothing to do with my identity whatsoever.

I'd write parts of this and would feel myself wanting to be like, "Oh but you know, I'm not a prude. I like 'WAP'!" I wanted to prove myself before anyone could dismiss me because of what I thought they believe about what it meant to be asexual. So it really showed me the extent to which I struggled to not be defensive, the extent to which I struggled to prove how 'down' I am, so ironically the extent to which I actually believed all of those things emotionally. I didn't, and I don't, intellectually.

Mashable :

Several asexual people you spoke with were also members of the kink community. From what I gleaned, there's a lot of emphasis on consent in kink, and there's intimacy in kink. Why do you think some asexual people may be drawn to the kink community?

Chen :

One reason is because, for them, it's just interesting. Obviously for some people, kink can be sexual. I'm not saying kink is inherently non-sexual, but I don't think it has to be. People have said they like the dynamics of it, they like the feeling of interesting sensations, the same way some people like the sensation of wearing velvet. It doesn't have to be sexual. They like the emotional dynamics of it even if it's not sexually gratifying to them. There are so many parts of kink that, while they can be sexual, it doesn't have to be for them.

The other reason many people have said is because they do think that the norms in kink often make it safer for them because there's better consent practices — which is not to say kink is perfect, every person in every culture can improve. But what people have said specifically is that it's encouraged to negotiate beforehand. If you're doing a scene together you're supposed to talk about what's okay and what's not. One woman I spoke to said something like, "I can say, 'I don't care if you get hard, I don't care if you get wet, I'm not going to do anything about it.'" And she felt like she could say that in the kink context. It was okay, it was encouraged, whereas she said that she felt less safe in the vanilla context because it was considered kind of libido-killing to negotiate these things. She would feel like if she stopped them, then it wouldn't be okay and she'd feel pressure. The norms [in kink] felt safer and better for her, even though I think many people have this erroneous assumption that kink is a dangerous place.

Mashable : What advice would you give someone questioning whether they're asexual or aromantic or both?

The

first thing I would say is that it's okay to question. There's so much pressure

on aces to be different, like we're encouraged to question too much. We're

encouraged to be like, "Oh, I'm not actually ace. I'm just shy, I just

haven't found the right person." That's not what I'm saying. But I do

think in general questioning is good because all of us change and all of us

have different experiences. Don't feel bad for questioning, even though you

don't have to question if you feel you already know who you are.

Give yourself a sense of space. I think it takes people a lot of time to understand this kind of lesser-known orientation and what it might be, and what integrating in the identity might mean for them. One thing that's interesting about ace identity is that everyone always says very specifically: Only you can decide if you're ace. I can't "diagnose" you as asexual and people will often say if this doesn't work for you — if identifying as asexual is harmful for you — then maybe you don't have to do it. I think giving yourself that kind of space is important.

People have reached out [after reading excerpts] and they'll say things like, "I feel so conflicted. In some ways, thinking about identifying as ace makes me feel so free. In other ways, it just makes me feel kind of bad about myself." And that's okay, too. Most of us have been conditioned to think of asexuality as something inferior — it's okay if you maybe have that reaction. Give yourself the time and the space that you need. You don't have to commit to anything right now.

Mashable : What broader hopes do you have for Ace?

Chen :

Many

aces know a lot of the basic stuff, but I think it's rare for them to see

actual narratives of other ace people. And of course, just because you're ace

doesn't mean you necessarily know what it might mean to be an ace person of

color if you're white, or to be disabled. There's many intersections and I hope

that's illuminating.

I also really hope it makes people just question and think about themselves as they're reading it, regardless of whether they're ace or not. Some people who've read galleys said, "You know, as I was reading this I started thinking, how do I define desire? Where am I on this ace/allo spectrum? Are there relationships that I thought were platonic but they were romantic but not sexual?" These are questions that people can all think about, especially questions regarding consent which I think is super important.

I hope that regardless of whatever someone's orientation might be, that they read this and apply it to themselves. Hopefully they can open up and think about the way we combine sex and desire and love and romance. A lot of times, they're all very separate things.

'Ace' is

the first book of its kind. Here’s why anyone, asexual or not, should read it.

By Anna Iovine. Mashable , September 10, 2020.